Can the Neo-Babylonian Chronology Be Lowered?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. the Biblical Data Regarding Darius the Mede

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Autumn 1982, Vol. 20, No. 3, 229-217. Copyright 0 1982 by Andrews University Press. DARIUS THE MEDE: AN UPDATE WILLIAM H. SHEA Andrews University The two main historical problems which confront us in the sixth chapter of Daniel have to do with the two main historical figures in it, Darius the Mede, who was made king of Babylon, and Daniel, whom he appointed as principal governor there. The problem with Darius is that no ruler of Babylon is known from our historical sources by this name prior to the time of Darius I of Persia (522-486 B.c.). The problem with Daniel is that no governor of Babylon is known by that name, or by his Babylonian name, early in the Persian period. Daniel's position mentioned here, which has received little attention, will be discussed in a sub- sequent study. In the present article I shall treat the question of the identification of Darius the Mede, a matter which has received considerable attention, with a number of proposals having been advanced as to his identity. I shall endeavor to bring some clarity to the picture through a review of the cuneiform evidence and a comparison of that evidence with the biblical data. As a back- ground, it will be useful also to have a brief overview of the various theories that have already been advanced. 1. The Biblical Data Regarding Darius the Mede Before we consider the theories regarding the identification of Darius the Mede, however, note should be taken of the information about him that is available from the book of Daniel. -

Assyrian Period (Ca. 1000•fi609 Bce)

CHAPTER 8 The Neo‐Assyrian Period (ca. 1000–609 BCE) Eckart Frahm Introduction This chapter provides a historical sketch of the Neo‐Assyrian period, the era that saw the slow rise of the Assyrian empire as well as its much faster eventual fall.1 When the curtain lifts, at the close of the “Dark Age” that lasted until the middle of the tenth century BCE, the Assyrian state still finds itself in the grip of the massive crisis in the course of which it suffered significant territorial losses. Step by step, however, a number of assertive and ruthless Assyrian kings of the late tenth and ninth centuries manage to reconquer the lost lands and reestablish Assyrian power, especially in the Khabur region. From the late ninth to the mid‐eighth century, Assyria experiences an era of internal fragmentation, with Assyrian kings and high officials, the so‐called “magnates,” competing for power. The accession of Tiglath‐pileser III in 745 BCE marks the end of this period and the beginning of Assyria’s imperial phase. The magnates lose much of their influence, and, during the empire’s heyday, Assyrian monarchs conquer and rule a territory of unprecedented size, including Babylonia, the Levant, and Egypt. The downfall comes within a few years: between 615 and 609 BCE, the allied forces of the Babylonians and Medes defeat and destroy all the major Assyrian cities, bringing Assyria’s political power, and the “Neo‐Assyrian period,” to an end. What follows is a long and shadowy coda to Assyrian history. There is no longer an Assyrian state, but in the ancient Assyrian heartland, especially in the city of Ashur, some of Assyria’s cultural and religious traditions survive for another 800 years. -

Style of Architecture, Consisting of Hard Backed Bricks, Molded in Such a Shape As to Fit Regularly to Each Other”

Journal of Earth Sciences and Geotechnical Engineering, Vol.10, No.3, 2020, 87-111 ISSN: 1792-9040 (print version), 1792-9660 (online) Scientific Press International Limited Babylon in a New Era: The Chaldean and Achaemenid Empires (330-612 BC) Nasrat Adamo1 and Nadhir Al-Ansari2 Abstract The new rise of Babylon is reported and its domination of the old world is described; when two dynasties ruled Neo- Babylonia from 612 BC to 330 BC. First, the Chaldeans had taken over from the Assyrians whom they had defeated and established their empire, which lasted for 77 years followed by the Achaemenid dynasty, which was to rule Babylonia for the remaining period as part of their empire. Out of the 77 years of the Chaldean period king, Nebuchadnezzar II ruled for 43 years, which were full of military achievements and construction works and organization. Apart from extending the borders of the empire, he had managed to construct large-scale hydraulic works which were intended for irrigation, navigation and even for defensive purposes. He excavated, re-excavated, and maintained four large feeder canals taking off from the Euphrates, which served the agriculture in the whole area between the Euphrates and the Tigris in the middle and lower Euphrates regions. Moreover, he was concerned with flood protection and so he constructed one large reservoir near Sippar at 60 km north of Babylon to be filled by the Euphrates excess water during floods and to be returned back to the river during low flow season in summer. His works involved river training projects, so he trained the Euphrates by digging artificial meanders to reduce the velocity of the flow and improving navigation and allow the construction of the canal intakes in a less turbulent flows. -

Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization

oi.uchicago.edu THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION JOHN ALBERT WILSON & THOMAS GEORGE ALLEN - EDITORS ELIZABETH B. HAUSER & RUTH S. BROOKENS • ASSISTANT EDITORS oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu BABYLONIAN CHRONOLOGY 626 B.G.-A.D. 45 oi.uchicago.edu THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS - CHICAGO THE BAKER & TAYLOR COMPANY • NEW YORK THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS • LONDON oi.uchicago.edu BABYLONIAN CHRONOLOGY 626 B.C.-A.D. 45 BT RICHARD A. PARKER AND WALDO H. DUB B ERSTE IX THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION • NO. 24 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS . CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu COPYRIGHT 1942 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PUBLISHED DECEMBER 1942. COMPOSED AND PRINTED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, U.S.A. oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE This study aims at providing a brief, but complete and thorough, presenta tion of the data bearing upon the chronological problems of the Neo-Baby- lonian, Achaemenid Persian, and Seleucid periods, together with tables for the easy translation of dates from the Babylonian calendar into the Julian. Recent additions to our knowledge of intercalary months in the Neo-Baby- lonian and Persian periods have enabled us to improve upon the results of our predecessors in this field, though our great debt to F. X. Kugler and D. Sider- sky for providing the background of our work is obvious. While our tables are intended primarily for historians, both classical and oriental, biblical students also should find them useful, as any biblical date of this period given in the Babylonian calendar can be translated by our tables. -

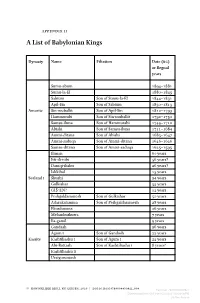

A List of Babylonian Kings

Appendix II A List of Babylonian Kings Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Sumu-abum 1894–1881 Sumu-la-El 1880–1845 Sabium Son of Sumu-la-El 1844–1831 Apil-Sin Son of Sabium 1830–1813 Amorite Sin-muballit Son of Apil-Sin 1812–1793 Hammurabi Son of Sin-muballit 1792–1750 Samsu-iluna Son of Hammurabi 1749–1712 Abishi Son of Samsu-iluna 1711–1684 Ammi-ditana Son of Abishi 1683–1647 Ammi-saduqa Son of Ammi-ditana 1646–1626 Samsu-ditana Son of Ammi-saduqa 1625–1595 Iliman 60 years Itti-ili-nibi 56 years? Damqi-ilishu 26 years? Ishkibal 15 years Sealand I Shushi 24 years Gulkishar 55 years GÍŠ-EN? 12 years Peshgaldaramesh Son of Gulkishar 50 years Adarakalamma Son of Peshgaldaramesh 28 years Ekurduanna 26 years Melamkurkurra 7 years Ea-gamil 9 years Gandash 26 years Agum I Son of Gandash 22 years Kassite Kashtiliashu I Son of Agum I 22 years Abi-Rattash Son of Kashtiliashu I 8 years? Kashtiliashu II Urzigurumash © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_009 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:29:36PM via free access A List of Babylonian Kings 203 Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Harba-Shipak Tiptakzi Agum II Son of Urzigurumash Burnaburiash I […]a Kashtiliashu III Son of Burnaburiash I? Ulamburiash Son of Burnaburiash I? Agum III Son of Kashitiliash IIIb Karaindash Kadashman-Harbe I Kurigalzu I Son of Kadashman-Harbe I Kadashman-Enlil I 1374?–1360 Burnaburiash II Son of Kadashman-Enlil I? 1359–1333 Karahardash Son of Burnaburiash II? 1333 Nazibugash Son of Nobody -

IV. a Re-Examination of the Nabonid~S Chonicle I

AN UNRECOGNIZED VASSAL KING OF BABYLON IN THE EARLY ACHAEMENID PERIOD WILLIAM H. SHEA Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, West Indies IV. A Re-examination of the Nabonid~sChonicle I. Comparative Materials Introd~ction.If a solution to the problem posed by the titulary of Cyrus in the economic texts is to be sought, perhaps it is not unexpected that the answer might be found in the Nabonidus Chronicle, since that text is the most specific historical document known that details the events of the time in question. However, there are several places in this re- consideration of the Nabonidus Chronicle where the practices of the Babylonian scribes who wrote the chronicle texts are examined, and for this reason other chronicle texts besides the Nabonidus Chronicle are referred to in this section. The texts that have been selected for such comparative purposes chronicle events from the two centuries preceding the time of the Nabonidus Chronicle. Coincidentally, the chronicle texts considered here begin with records from the reign of Nabonas- sar in the middle of the 8th century B.c., the same time when the royal titulary in the economic texts began to show the changes discussed in the earlier part of this study. Although there are gaps in the information available from the chronicles for these two centuries, we are fortunate to have ten texts that chronicle almost one-half of the regnal years from the time of Nabonassar to the time of Cyrus (745-539). The texts utilized in this study of the chronicles are listed in Table V. * The first two parts of this article were published in A USS, IX (1971), 51-67, 99-128. -

Babylonian Empire 9/13/11 3:47 PM

Babylonian Empire 9/13/11 3:47 PM home : index : ancient Mesopotamia : article by Jona Lendering © Babylonian Empire The Babylonian Empire was the most powerful state in the ancient world after the fall of the Assyrian empire (612 BCE). Its capital Babylon was beautifully adorned by king Nebuchadnezzar, who erected several famous buildings. Even after the Babylonian Empire had been overthrown by the Persian king Cyrus the Great (539), the city itself remained an important cultural center. Old Babylonian Period Kassite Period Old Babylonian Period Middle Babylonian Period Assyrian Period King Hammurabi and Šamaš Capital of the stele with the Laws The city of Babylon makes its first appearance in our sources after the Neo-Babylonian Period of Hammurabi (Louvre) fall of the Empire of the Third Dynasty of Ur, which had ruled the city Later history states of the alluvial plain between the rivers Euphrates and Tigris for Related more than a century (2112-2004?). An agricultural crisis meant the Mesopotamian Kings end of this centralized state, and several more or less nomadic tribes Chronology settled in southern Mesopotamia. One of these was the nation of the Amorites ("westerners"), which took over Isin, Larsa, and Babylon. Their kings are known as the First Dynasty of Babylon (1894-1595?). The area was reunited by Hammurabi, a king of Babylon of Amorite descent (1792-1750?). From his reign on, the alluvial plain of southern Iraq was called, with a deliberate archaism, Mât Akkadî, "the country of Akkad", after the city that had united the region centuries before. We call it Babylonia. -

The Babyloniaca of Berossus

sources and monographs sources from the ancient near east volume 1, fascicle 5 the babyloniaca of berossus by Stanley Mayer Burstein undena publication malibu 1978 ABBREVIATIONS ANET Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (1948) FGrH Die Fragmente der grieschischen Historiker (1923-1958) Grayson Texts from Cuneiform Sources, vol. 5, Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles (1975) JCS Journal of Cuneiform Studies RLA Reallexicon der Assyriologie (1928-1938; 1957-) RE Real-Encycloplidie der klassischen A ltertumswissenschaft [SANE 1, 143) TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations ................................................................... 1 Table of Contents . ............... 3 A. Introduction .................................................................4 1. The Hellenistic Period and Ancient Near Eastern Civilization .............................. .4 2. The Life of Berossus . 5 3. The Babyloniaca . ................. 6 4. Evaluation .........................................•...................... 8 5. The Present Edition ......................................................... IO B. Book One: Genesis ........................................................... 13 1. Prologue . 13 2. The Revelation ofOannes ..................................................... 14 3. The Great Year ......... : .................................................. 15 4. The Moon ............................................................... 16 5. The Walling of Babylon ...................................................... 17 6. Unplaced Fragments -

Daniel, Darius the Median, Cyrus the Great;

d',:i5.2:3 3Fnim t\^t SItbraro of Srqu0atl|fb bg l|tm to tl|F iCtbrary of Prinreton ®l|eol0gtral S>^mittarQ BSi i97 J. H8I DANIEL DARIUS THE MEDIAN CYRUS THE GREAT A Chronologico- Historical Study Based on Results of Recent Researches, and from Sources Hebrew, Greek, Cuneiform, etc. / BY Rev. Joseph Horner, D.D., LL.D, Member of the Society of Biblical Archaeology London, England Pittsburgh, Pa. JOSEPH HORNER EATON & mains: - - NEW YORK JENNINGS & PYE : - - CINCINNATI Copyright, Joseph Horner 1901 CONTENTS PAGS Preface 5 Preliminary 7 I. The Story of Daniel 9 II. War of Cyrus with Astyages, and Date of His Over- throw 42 III. The Persons and Other Matters Pertaining to the Taking of Babylon and the Extinction of the Babylono-Chaldean Empire 61 IV. Identification of Darius the Median 74 V. Matters Subsidiary , 114 PREFACE It was at first proposed to give a title-page to this work which would present a general view of its con- tents. That could be done, it was thought, somewhat after this manner: "Daniel, Darius the Median, and Cyrus the Great; an authentication of Daniel's book,- an identification of the Median, an elucidation, in part, of the story of the Great King, and parts of the books of Jeremiah and Ezra ; aiming, by information derived from recent researches, and from sources Hebrew, Greek, Cuneiform, etc., to bring more clearly into view the general and singular accuracy of the Biblical historical notes, for the period from the fall of Nineveh, B. C. 607, to the reign of Darius the Persian, son of Hystaspes, B. -

Copyrighted Material

Contents List of Illustrations xii List of Tables xiv List of Maps xvi Preface xvii List of Abbreviations xix Author’s Note xx 1 Introductory Concerns 1 1.1 Assyriology and the Writing of History 3 1.1.1 Cuneiform Texts as Historical Sources 4 1.2 Historical Science and the Handling of Sources 17 1.3 Chronology 20 2 The Sumero‐Akkadian Background 24 2.1 Babylonia as Geographic Unit 24 2.2 The Natural Environment 25 2.3 The Neolithic Revolution 28 2.4 The UbaidCOPYRIGHTED Period (6500–4000) MATERIAL 29 2.5 The Uruk Period (4000–3100) 30 2.6 The Jemdet Nasr Period (3100–2900) 31 2.7 The Early Dynastic Period (2900–2350) 34 2.7.1 The State of Lagash 38 2.7.2 Babylon in the Early Dynastic Period 40 2.8 The Sargonic (Old Akkadian) and Gutian Periods (ca. 2334–2113) 41 2.8.1 Akkadian and Sumerian Linguistic Areas 42 2.8.2 The Early Sargonic Period (ca. 2334–2255) 44 0003319927.INDD 7 11/15/2017 4:19:51 PM viii CONTENTS 2.8.3 The Classical Sargonic Period (ca. 2254–2193) 46 2.8.4 Babylon in the Sargonic Period 50 2.8.5 The Late Sargonic (ca. 2193–2154) and Gutian Periods (ca. 2153–2113) 51 2.9 The Third Dynasty of Ur (2112–2004) 52 2.9.1 King of Sumer and Akkad 53 2.9.2 Shulgi’s Babylonia 54 2.9.3 Failure of the Ur III State 56 2.9.4 Babylon during the Ur III Period 57 3 The Rise of Babylon 60 3.1 The First Dynasty of Isin (2017–1794) 62 3.2 The Amorites 64 3.2.1 Amorite Genealogies and Histories 66 3.3 Date Lists and King Lists of Babylon I 68 3.4 Elusive Beginnings 69 3.5 Sumu‐la‐el (1880–1845) 70 3.5.1 The Letter of Anam and the Babylon‐Uruk -

Introduction

THE ACCESSION OF ARTAXERXES I JULIA NEUFFER Washington, D.C. Introduction This article is principally a reexamination of the source data relevant to the accession date of the Persian king Artaxerxes I, and especially a study of a double-dated papyrus from Egypt that was, until a few years ago, the only known ancient document assigning an approximate date to that event. The "first year" and, therefore, the other years of his reign have long been known in two calendars. According to Ptolemy's Canon, which is fixed by eclipses, and according to certain double-dated papyri from Egypt (to be discussed below), his year I in the Egyptian calendar was the 365-day year beginning on Thoth I, the Egyptian New Year's Day (that is, December 17), 465 B.C. In the Persian reckoning (in the Babylonian calendar, which was adopted by the Persian kings), his first year was the lunar year beginning in the spring, with Nisanu (Jewish Nisan) I, approximately April 13, 464, several months later than the Egyptian year. Postdating and Antedating. This Persian reckoning means that his reign must have begun before Nisan I, 464, because the Babylonian-Persian method was to postdate all reigns. That is, when a new king succeeded to the throne the scribes, who had been dating all kinds of documents by the day and month "in the z~st[or whatever] year of King X," would begin using the new dateline "in the accession year [literally, The equivalents of Persian dates in this article are taken from the reconstructed calendar tables in Richard A. -

Zephaniah, Nahum and Habakkuk the Books of the Prophets Zephaniah and Nahum with Introduction and Notes by the Late G

WESTMINSTE~ CO~IMENTARIES EDITED BY WALTER LOCK D.D. FORMERLY LADY MARGARET PROPESBOR OF DIVINITY IN THE UNIVERSITY 011 OX110RD .AND D. c. SUIPSON D.D. ORIEL PROFEBBOR 011 THE INTlill.Pll.li• TATION 011 HOLY BCll.IPTUll.E, CANON OJI' 11.0CIIESTER. THE BOOKS OF THE PROPHETS ZEPHANIAH, NAHUM AND HABAKKUK THE BOOKS OF THE PROPHETS ZEPHANIAH AND NAHUM WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY THE LATE G. G. v. STONEHOUSE B.D. THE BOOK OF THE PROPHET HABAKKUK WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY G. W. WADE D.D. BBNIOR TUTOR OJI' ST DA. VID'S COLLEGB, LA.JllPBTBR CA.1!1O1!1 OJI' BT A.SA.PR METHUEN & CO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET W.C. LONDON First Published in 1929 l'llINTEil IN GllEAT BlllTAIN PREFATORY NOTE BY THE GENERAL EDITORS HE primary ob~ect of these Commentaries is to be exegetical, Tto interpret the meaning of each book of the Bible in the light of modern knowledge to English readers. The Editors will not deal, except subordinately, with questions of textual criticism or philology; but taking the English text in the Revised Version as their basis, they will aim at combining a hearty acceptance of critical principles with loyalty to the Catholic Faith. The series will be less elementary than the Cambridge Bible for Schoo_ls, less critical than the International Critical Com mentary, less didactic than the Expositor's Bible; and it is hoped that it may be of use both to theological students and fo the clergy, as well as to the growing number of educated laymen and laywomen who wish to read the Bible intelligently and reverently.