Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An In-Depth Study of the Tell Brak Eye Idols in the 4Th Millennium BCE: with a Primary Focus on Function and Meaning

1 The Eyes Have It An In-Depth Study of the Tell Brak Eye Idols in the 4th Millennium BCE: with a primary focus on function and meaning Honours Thesis Department of Archaeology The University of Sydney Arabella Cooper 430145722 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in the Department of Archaeology at the University of Sydney, Australia, 2016. 2 “In the present state of our knowledge there are very few archaeological discoveries which can be described as unique, but one class of objects from Brak is unique-the eye-idols or images which turned up in thousands in the grey brick stratum of the earlier Eye-Temple" M.E.L Mallowan, 1947, Excavations at Brak and Chagar Bazar, 33. Cover Image: Figures 1-5. M.E.L Mallowan, 1947, Excavations at Brak and Chagar Bazar, 33. 3 Statement of Authorship The research described in this thesis, except where referenced, is the original work of the author and was a discrete project supervised by Dr Alison Betts. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other individual’s work has been used without accurate referencing and acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. Arabella Cooper, November 2016 4 Acknowledgments As with any major study or work, you do not toil in isolation and the writing of this thesis is no different. I first would like to thank my supervisor Professor Alison Betts, and even more so the wonderful staff at the Nicholson Museum Candace Richards and Karen Alexander for their patience and advise. -

Thiele's Biblical Chronology As a Corrective for Extrabiblical Dates

Andm University Seminary Studies, Autumn 1996, Vol. 34, No. 2,295-317. Copyright 1996 by Andrews University Press.. THIELE'S BIBLICAL CHRONOLOGY AS A CORRECTIVE FOR EXTRABIBLICAL DATES KENNETH A. STRAND Andrews University The outstanding work of Edwin R. Thiele in producing a coherent and internally consistent chronology for the period of the Hebrew Divided Monarchy is well known. By ascertaining and applying the principles and procedures used by the Hebrew scribes in recording the lengths of reign and synchronisms given in the OT books of Kings and Chronicles for the kings of Israel and Judah, he was able to demonstrate the accuracy of these biblical data. What has generally not been given due notice is the effect that Thiele's clarification of the Hebrew chronology of this period of history has had in furnishing a corrective for various dates in ancient Assyrian and Babylonian history. It is the purpose of this essay to look at several such dates.' 1. i%e Basic Question In a recent article in AUSS, Leslie McFall, who along with many other scholars has shown favor for Thiele's chronology, notes five vital variable factors which Thiele recognized, and then he sets forth the following opinion: In view of the complex interaction of several of the independent factors, it is clear that such factors could never have been discovered (or uncovered) if it had not been for extrabiblical evidence which established certain key absolute dates for events in Israel and Judah, such as 853, 841, 723, 701, 605, 597, and 586 B.C. It was as a result of trial and error in fitting the biblical data around these absolute dates that previous chronologists (and more recently Thiele) brought to light the factors outlined above.= '~lthou~hmuch of the information provided in this article can be found in Thiele's own published works, the presentation given here gathers it, together with certain other data, into a context and with a perspective not hitherto considered, so far as I have been able to determine. -

Sea-L 3 Jeverling Materials Vol1.Pdf

SPECIMINA ELECTRONICA ANTIQUITATIS – LIBRI 3. 2013 ₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪ ISBN 978-963-642-508-1 Materials for the Study of First Millennium B.C. Babylonian Texts Volume 1. Chronological List of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia János Everling Pécs 2000 Matrials for the Study of the First Millennium B.C. Babylonian Texts vol. 1. Chronological List 1. Introduction Since the publication of the Chronological List of the Ur III texts 1 the attention of several scholars were drawn to the lack of information in the same field concerning the First Millennium B.C. The first attempt to complete our knowledge concerning this period were realized by M. Dandamayev2. Next year R. Zadok published a comprehensive study on the geographical repartition of the material3. Several studies were elaborated for the reconstruction of the first millennium B.C. Babylonian chronology4. The first volume of the “Materials for the Study of the First Millennium B.C. Babylonian Texts” is intended to present the material in chronological order. It was completed in September 2000. The “Materials for the Study of the First Millennium B.C. Babylonian Texts” is a series of volumes whose logical structure can be described as follows: 1. Chronological List of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia, 2. Geographical List of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia, 3. Personal Names of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia, 4. Thematic Selections from the Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. Babylonia, 5. Publication of Text Editions of Babylonian Texts from the First Millennium B.C. -

1. the Biblical Data Regarding Darius the Mede

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Autumn 1982, Vol. 20, No. 3, 229-217. Copyright 0 1982 by Andrews University Press. DARIUS THE MEDE: AN UPDATE WILLIAM H. SHEA Andrews University The two main historical problems which confront us in the sixth chapter of Daniel have to do with the two main historical figures in it, Darius the Mede, who was made king of Babylon, and Daniel, whom he appointed as principal governor there. The problem with Darius is that no ruler of Babylon is known from our historical sources by this name prior to the time of Darius I of Persia (522-486 B.c.). The problem with Daniel is that no governor of Babylon is known by that name, or by his Babylonian name, early in the Persian period. Daniel's position mentioned here, which has received little attention, will be discussed in a sub- sequent study. In the present article I shall treat the question of the identification of Darius the Mede, a matter which has received considerable attention, with a number of proposals having been advanced as to his identity. I shall endeavor to bring some clarity to the picture through a review of the cuneiform evidence and a comparison of that evidence with the biblical data. As a back- ground, it will be useful also to have a brief overview of the various theories that have already been advanced. 1. The Biblical Data Regarding Darius the Mede Before we consider the theories regarding the identification of Darius the Mede, however, note should be taken of the information about him that is available from the book of Daniel. -

Representations of Plants on the Warka Vase of Early Mesopotamia

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons University of Pennsylvania Museum of University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Papers Archaeology and Anthropology 2016 Sign and Image: Representations of Plants on the Warka Vase of Early Mesopotamia Naomi F. Miller University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Philip Jones University of Pennsylvania Holly Pittman University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Botany Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Miller, Naomi F., Philip Jones, and Holly Pittman. 2016. Sign and image: representations of plants on the Warka Vase of early Mesopotamia. Origini 39: 53–73. University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons, Philadelphia. http://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers/2 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers/2 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sign and Image: Representations of Plants on the Warka Vase of Early Mesopotamia Abstract The Warka Vase is an iconic artifact of Mesopotamia. In the absence of rigorous botanical study, the plants depicted on the lowest register are usually thought to be flax and grain. This analysis of the image identified as grain argues that its botanical characteristics, iconographical context and similarity to an archaic sign found in proto-writing demonstrates that it should be identified as a date palm sapling. It confirms the identification of flax. The correct identification of the plants furthers our understanding of possible symbolic continuities spanning the centuries that saw the codification of text as a eprr esentation of natural language. -

Assyrian Period (Ca. 1000•fi609 Bce)

CHAPTER 8 The Neo‐Assyrian Period (ca. 1000–609 BCE) Eckart Frahm Introduction This chapter provides a historical sketch of the Neo‐Assyrian period, the era that saw the slow rise of the Assyrian empire as well as its much faster eventual fall.1 When the curtain lifts, at the close of the “Dark Age” that lasted until the middle of the tenth century BCE, the Assyrian state still finds itself in the grip of the massive crisis in the course of which it suffered significant territorial losses. Step by step, however, a number of assertive and ruthless Assyrian kings of the late tenth and ninth centuries manage to reconquer the lost lands and reestablish Assyrian power, especially in the Khabur region. From the late ninth to the mid‐eighth century, Assyria experiences an era of internal fragmentation, with Assyrian kings and high officials, the so‐called “magnates,” competing for power. The accession of Tiglath‐pileser III in 745 BCE marks the end of this period and the beginning of Assyria’s imperial phase. The magnates lose much of their influence, and, during the empire’s heyday, Assyrian monarchs conquer and rule a territory of unprecedented size, including Babylonia, the Levant, and Egypt. The downfall comes within a few years: between 615 and 609 BCE, the allied forces of the Babylonians and Medes defeat and destroy all the major Assyrian cities, bringing Assyria’s political power, and the “Neo‐Assyrian period,” to an end. What follows is a long and shadowy coda to Assyrian history. There is no longer an Assyrian state, but in the ancient Assyrian heartland, especially in the city of Ashur, some of Assyria’s cultural and religious traditions survive for another 800 years. -

Style of Architecture, Consisting of Hard Backed Bricks, Molded in Such a Shape As to Fit Regularly to Each Other”

Journal of Earth Sciences and Geotechnical Engineering, Vol.10, No.3, 2020, 87-111 ISSN: 1792-9040 (print version), 1792-9660 (online) Scientific Press International Limited Babylon in a New Era: The Chaldean and Achaemenid Empires (330-612 BC) Nasrat Adamo1 and Nadhir Al-Ansari2 Abstract The new rise of Babylon is reported and its domination of the old world is described; when two dynasties ruled Neo- Babylonia from 612 BC to 330 BC. First, the Chaldeans had taken over from the Assyrians whom they had defeated and established their empire, which lasted for 77 years followed by the Achaemenid dynasty, which was to rule Babylonia for the remaining period as part of their empire. Out of the 77 years of the Chaldean period king, Nebuchadnezzar II ruled for 43 years, which were full of military achievements and construction works and organization. Apart from extending the borders of the empire, he had managed to construct large-scale hydraulic works which were intended for irrigation, navigation and even for defensive purposes. He excavated, re-excavated, and maintained four large feeder canals taking off from the Euphrates, which served the agriculture in the whole area between the Euphrates and the Tigris in the middle and lower Euphrates regions. Moreover, he was concerned with flood protection and so he constructed one large reservoir near Sippar at 60 km north of Babylon to be filled by the Euphrates excess water during floods and to be returned back to the river during low flow season in summer. His works involved river training projects, so he trained the Euphrates by digging artificial meanders to reduce the velocity of the flow and improving navigation and allow the construction of the canal intakes in a less turbulent flows. -

Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization

oi.uchicago.edu THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION JOHN ALBERT WILSON & THOMAS GEORGE ALLEN - EDITORS ELIZABETH B. HAUSER & RUTH S. BROOKENS • ASSISTANT EDITORS oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu BABYLONIAN CHRONOLOGY 626 B.G.-A.D. 45 oi.uchicago.edu THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS - CHICAGO THE BAKER & TAYLOR COMPANY • NEW YORK THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS • LONDON oi.uchicago.edu BABYLONIAN CHRONOLOGY 626 B.C.-A.D. 45 BT RICHARD A. PARKER AND WALDO H. DUB B ERSTE IX THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION • NO. 24 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS . CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu COPYRIGHT 1942 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PUBLISHED DECEMBER 1942. COMPOSED AND PRINTED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, U.S.A. oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE This study aims at providing a brief, but complete and thorough, presenta tion of the data bearing upon the chronological problems of the Neo-Baby- lonian, Achaemenid Persian, and Seleucid periods, together with tables for the easy translation of dates from the Babylonian calendar into the Julian. Recent additions to our knowledge of intercalary months in the Neo-Baby- lonian and Persian periods have enabled us to improve upon the results of our predecessors in this field, though our great debt to F. X. Kugler and D. Sider- sky for providing the background of our work is obvious. While our tables are intended primarily for historians, both classical and oriental, biblical students also should find them useful, as any biblical date of this period given in the Babylonian calendar can be translated by our tables. -

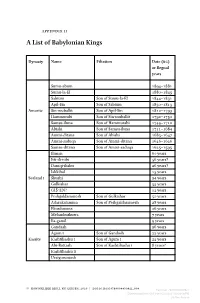

A List of Babylonian Kings

Appendix II A List of Babylonian Kings Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Sumu-abum 1894–1881 Sumu-la-El 1880–1845 Sabium Son of Sumu-la-El 1844–1831 Apil-Sin Son of Sabium 1830–1813 Amorite Sin-muballit Son of Apil-Sin 1812–1793 Hammurabi Son of Sin-muballit 1792–1750 Samsu-iluna Son of Hammurabi 1749–1712 Abishi Son of Samsu-iluna 1711–1684 Ammi-ditana Son of Abishi 1683–1647 Ammi-saduqa Son of Ammi-ditana 1646–1626 Samsu-ditana Son of Ammi-saduqa 1625–1595 Iliman 60 years Itti-ili-nibi 56 years? Damqi-ilishu 26 years? Ishkibal 15 years Sealand I Shushi 24 years Gulkishar 55 years GÍŠ-EN? 12 years Peshgaldaramesh Son of Gulkishar 50 years Adarakalamma Son of Peshgaldaramesh 28 years Ekurduanna 26 years Melamkurkurra 7 years Ea-gamil 9 years Gandash 26 years Agum I Son of Gandash 22 years Kassite Kashtiliashu I Son of Agum I 22 years Abi-Rattash Son of Kashtiliashu I 8 years? Kashtiliashu II Urzigurumash © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_009 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:29:36PM via free access A List of Babylonian Kings 203 Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Harba-Shipak Tiptakzi Agum II Son of Urzigurumash Burnaburiash I […]a Kashtiliashu III Son of Burnaburiash I? Ulamburiash Son of Burnaburiash I? Agum III Son of Kashitiliash IIIb Karaindash Kadashman-Harbe I Kurigalzu I Son of Kadashman-Harbe I Kadashman-Enlil I 1374?–1360 Burnaburiash II Son of Kadashman-Enlil I? 1359–1333 Karahardash Son of Burnaburiash II? 1333 Nazibugash Son of Nobody -

IV. a Re-Examination of the Nabonid~S Chonicle I

AN UNRECOGNIZED VASSAL KING OF BABYLON IN THE EARLY ACHAEMENID PERIOD WILLIAM H. SHEA Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, West Indies IV. A Re-examination of the Nabonid~sChonicle I. Comparative Materials Introd~ction.If a solution to the problem posed by the titulary of Cyrus in the economic texts is to be sought, perhaps it is not unexpected that the answer might be found in the Nabonidus Chronicle, since that text is the most specific historical document known that details the events of the time in question. However, there are several places in this re- consideration of the Nabonidus Chronicle where the practices of the Babylonian scribes who wrote the chronicle texts are examined, and for this reason other chronicle texts besides the Nabonidus Chronicle are referred to in this section. The texts that have been selected for such comparative purposes chronicle events from the two centuries preceding the time of the Nabonidus Chronicle. Coincidentally, the chronicle texts considered here begin with records from the reign of Nabonas- sar in the middle of the 8th century B.c., the same time when the royal titulary in the economic texts began to show the changes discussed in the earlier part of this study. Although there are gaps in the information available from the chronicles for these two centuries, we are fortunate to have ten texts that chronicle almost one-half of the regnal years from the time of Nabonassar to the time of Cyrus (745-539). The texts utilized in this study of the chronicles are listed in Table V. * The first two parts of this article were published in A USS, IX (1971), 51-67, 99-128. -

A Group of Cylinder Seals from the Diyarbakir Museum

Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi SUSBID Journal Of Social Sciences Institute 2020: 32 - 56 SAYI: 15 ISSN: 2147-8406 Research Article / Araştırma Makalesi A GROUP OF CYLINDER SEALS FROM THE DİYARBAKIR MUSEUM Çağatay YÜCEL1 Umut PARLITI2 Abstract The geometric cylindrical seals that were brought to the museum through confiscation and acquisition were handled in the works stored in the purchasing depot of the Diyarbakır Archaeological Museum. The period of cylinder seals, their function and the expression scenes on them are examined. As a result of the evaluation of the cylinder seals included in the study, historical and cultural framework was tried to be formed by considering the socio-cultural structure of the age. The origin of the Mesopotamian societies, their life- styles, religions and their relations with each other are also discussed in connection with the cylinder seals chosen as the subject of the study. Parallel to this, the general definition of the seal has been made with respect to the cylinder seals included in the study. As a re- sult of the evaluation of cylinder seals, their contributions to Anatolian Archaeology were examined. The period of cylinder seals, their function and the expression scenes on them are examined. As a result of the evaluation of the cylinder seals included in the study, historical and cultural framework was tried to be formed by considering the socio-cultural structure of the age. Because cylinder seals are the most important works of art that reflect the belief and mythology of ancient societies. They are also the most important tool seals that deter- mine the economic activities of ancient societies. -

Babylonian Empire 9/13/11 3:47 PM

Babylonian Empire 9/13/11 3:47 PM home : index : ancient Mesopotamia : article by Jona Lendering © Babylonian Empire The Babylonian Empire was the most powerful state in the ancient world after the fall of the Assyrian empire (612 BCE). Its capital Babylon was beautifully adorned by king Nebuchadnezzar, who erected several famous buildings. Even after the Babylonian Empire had been overthrown by the Persian king Cyrus the Great (539), the city itself remained an important cultural center. Old Babylonian Period Kassite Period Old Babylonian Period Middle Babylonian Period Assyrian Period King Hammurabi and Šamaš Capital of the stele with the Laws The city of Babylon makes its first appearance in our sources after the Neo-Babylonian Period of Hammurabi (Louvre) fall of the Empire of the Third Dynasty of Ur, which had ruled the city Later history states of the alluvial plain between the rivers Euphrates and Tigris for Related more than a century (2112-2004?). An agricultural crisis meant the Mesopotamian Kings end of this centralized state, and several more or less nomadic tribes Chronology settled in southern Mesopotamia. One of these was the nation of the Amorites ("westerners"), which took over Isin, Larsa, and Babylon. Their kings are known as the First Dynasty of Babylon (1894-1595?). The area was reunited by Hammurabi, a king of Babylon of Amorite descent (1792-1750?). From his reign on, the alluvial plain of southern Iraq was called, with a deliberate archaism, Mât Akkadî, "the country of Akkad", after the city that had united the region centuries before. We call it Babylonia.