Daniel, Darius the Median, Cyrus the Great;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artaxerxes II

Artaxerxes II John Shannahan BAncHist (Hons) (Macquarie University) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Ancient History, Macquarie University. May, 2015. ii Contents List of Illustrations v Abstract ix Declaration xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Conventions xv Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY REIGN OF ARTAXERXES II The Birth of Artaxerxes to Cyrus’ Challenge 15 The Revolt of Cyrus 41 Observations on the Egyptians at Cunaxa 53 Royal Tactics at Cunaxa 61 The Repercussions of the Revolt 78 CHAPTER 2 399-390: COMBATING THE GREEKS Responses to Thibron, Dercylidas, and Agesilaus 87 The Role of Athens and the Persian Fleet 116 Evagoras the Opportunist and Carian Commanders 135 Artaxerxes’ First Invasion of Egypt: 392/1-390/89? 144 CHAPTER 3 389-380: THE KING’S PEACE AND CYPRUS The King’s Peace (387/6): Purpose and Influence 161 The Chronology of the 380s 172 CHAPTER 4 NUMISMATIC EXPRESSIONS OF SOLIDARITY Coinage in the Reign of Artaxerxes 197 The Baal/Figure in the Winged Disc Staters of Tiribazus 202 Catalogue 203 Date 212 Interpretation 214 Significance 223 Numismatic Iconography and Egyptian Independence 225 Four Comments on Achaemenid Motifs in 227 Philistian Coins iii The Figure in the Winged Disc in Samaria 232 The Pertinence of the Political Situation 241 CHAPTER 5 379-370: EGYPT Planning for the Second Invasion of Egypt 245 Pharnabazus’ Invasion of Egypt and Aftermath 259 CHAPTER 6 THE END OF THE REIGN Destabilisation in the West 267 The Nature of the Evidence 267 Summary of Current Analyses 268 Reconciliation 269 Court Intrigue and the End of Artaxerxes’ Reign 295 Conclusion: Artaxerxes the Diplomat 301 Bibliography 309 Dies 333 Issus 333 Mallus 335 Soli 337 Tarsus 338 Unknown 339 Figures 341 iv List of Illustrations MAP Map 1 Map of the Persian Empire xviii-xix Brosius, The Persians, 54-55 DIES Issus O1 Künker 174 (2010) 403 333 O2 Lanz 125 (2005) 426 333 O3 CNG 200 (2008) 63 333 O4 Künker 143 (2008) 233 333 R1 Babelon, Traité 2, pl. -

The Outbreak of the Rebellion of Cyrus the Younger Jeffrey Rop

The Outbreak of the Rebellion of Cyrus the Younger Jeffrey Rop N THE ANABASIS, Xenophon asserts that the Persian prince Cyrus the Younger was falsely accused of plotting a coup I d’état against King Artaxerxes II shortly after his accession to the throne in 404 BCE. Spared from execution by the Queen Mother Parysatis, Cyrus returned to Lydia determined to seize the throne for himself. He secretly prepared his rebellion by securing access to thousands of Greek hoplites, winning over Persian officials and most of the Greek cities of Ionia, and continuing to send tribute and assurances of his loyalty to the unsuspecting King (1.1).1 In Xenophon’s timeline, the rebellion was not official until sometime between the muster of his army at Sardis in spring 401, which spurred his rival Tissaphernes to warn Artaxerxes (1.2.4–5), and his arrival several months later at Thapsacus on the Euphrates, where Cyrus first openly an- nounced his true intentions (1.4.11). Questioning the “strange blindness” of Artaxerxes in light of Cyrus’ seemingly obvious preparations for revolt, Pierre Briant proposed an alternative timeline placing the outbreak of the rebellion almost immediately after Cyrus’ return to Sardis in late 404 or early 403.2 In his reconstruction, the King allowed Cyrus 1 See also Ctesias FGrHist 688 F 16.59, Diod. 14.19, Plut. Artax. 3–4. 2 Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander (Winona Lake 2002) 617–620. J. K. Anderson, Xenophon (New York 1974) 80, expresses a similar skepticism. Briant concludes his discussion by stating that the rebellion officially (Briant does not define “official,” but I take it to mean when either the King or Cyrus declared it publicly) began in 401 with the muster of Cyrus’ army at Sardis, but it is nonetheless appropriate to characterize Briant’s position as dating the official outbreak of the revolt to 404/3. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

1. the Biblical Data Regarding Darius the Mede

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Autumn 1982, Vol. 20, No. 3, 229-217. Copyright 0 1982 by Andrews University Press. DARIUS THE MEDE: AN UPDATE WILLIAM H. SHEA Andrews University The two main historical problems which confront us in the sixth chapter of Daniel have to do with the two main historical figures in it, Darius the Mede, who was made king of Babylon, and Daniel, whom he appointed as principal governor there. The problem with Darius is that no ruler of Babylon is known from our historical sources by this name prior to the time of Darius I of Persia (522-486 B.c.). The problem with Daniel is that no governor of Babylon is known by that name, or by his Babylonian name, early in the Persian period. Daniel's position mentioned here, which has received little attention, will be discussed in a sub- sequent study. In the present article I shall treat the question of the identification of Darius the Mede, a matter which has received considerable attention, with a number of proposals having been advanced as to his identity. I shall endeavor to bring some clarity to the picture through a review of the cuneiform evidence and a comparison of that evidence with the biblical data. As a back- ground, it will be useful also to have a brief overview of the various theories that have already been advanced. 1. The Biblical Data Regarding Darius the Mede Before we consider the theories regarding the identification of Darius the Mede, however, note should be taken of the information about him that is available from the book of Daniel. -

Mercenaries, Poleis, and Empires in the Fourth Century Bce

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts ALL THE KING’S GREEKS: MERCENARIES, POLEIS, AND EMPIRES IN THE FOURTH CENTURY BCE A Dissertation in History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies by Jeffrey Rop © 2013 Jeffrey Rop Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 ii The dissertation of Jeffrey Rop was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark Munn Professor of Ancient Greek History and Greek Archaeology, Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Gary N. Knoppers Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, Religious Studies, and Jewish Studies Garrett G. Fagan Professor of Ancient History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Kenneth Hirth Professor of Anthropology Carol Reardon George Winfree Professor of American History David Atwill Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies Graduate Program Director for the Department of History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Greek mercenary service in the Near East from 401- 330 BCE. Traditionally, the employment of Greek soldiers by the Persian Achaemenid Empire and the Kingdom of Egypt during this period has been understood to indicate the military weakness of these polities and the superiority of Greek hoplites over their Near Eastern counterparts. I demonstrate that the purported superiority of Greek heavy infantry has been exaggerated by Greco-Roman authors. Furthermore, close examination of Greek mercenary service reveals that the recruitment of Greek soldiers was not the purpose of Achaemenid foreign policy in Greece and the Aegean, but was instead an indication of the political subordination of prominent Greek citizens and poleis, conducted through the social institution of xenia, to Persian satraps and kings. -

Ctesias and the Fall of Nineveh

Ctesias and the Fall of Nineveh J.D.A. MACGINNIS The Persica of Ctesias are not extant but fragments are preserved in the works of many other ancient writers, notably Diodorus Siculus and Photius; Konig 1972 is an excellent edition of these excerpts.' The purpose of this article is to suggest that certain elements in Ctesias' description of the fall of Nineveh (best surviving in Diodorus Il.xxiv-xxviii) go back to details actually derived from an earlier siege and fall of Babylon. This is not to deny that the narrative of Ctesias—insofar as it is historical—does preserve material genuinely traceable to the fall of Nineveh, only that it has further incorporated extraneous particulars. Thus the barest outline of a Babylonian and a Median king uniting to bring about the end of the Assyrian empire is correct (Smith, 126-31; Roux 1980, 343^7) though the exact chronology has been much disputed (see J. Gates in the forthcoming volume 3. 2 of the new Cambridge Ancient History). Furthermore, the names of the protagonists are confused: Belesys could just be a corruption of Nabu-apla- usur (Nabopolassar) but Arbaces cannot be Umakishtar / Cyaxares, and in fact the suggestion of Jacoby (col. 2049) that Ctesias has inserted the names of two leading Persian officials of the time known from Xenophon, namely the Arbaces who commanded at Cunaxa and the Belesys who was satrap of Syria, is convincing. Another mistake in the Greek accounts is making the last king of Assyria Sardanapallos, that is Ashurbanipal. In fact the last king was Sinshar-ishkun; among the writers of antiquity only Abydenus names him correctly in the form Sarakos (Gadd 1923, p. -

The Nature of Maussollos's Monarchy

The Nature of Maussollos’s Monarchy The Three Faces of a Dynastic Karian Satrap by Mischa Piekosz [email protected] Utrecht University RMA-THESIS Research Master Ancient Studies Supervisor: Rolf Strootman Second Reader: Saskia Stevens Student Number 3801128 Abstract This thesis analyses the nature of Maussollos’s monarchy by looking at his (self-)representation in epigraphy, architecture, coinage, and use of titulature vis-a-vis the concept of Hellenistic kingship. It shall be argued that he represented himself and was represented in three different ways – giving him three different ‘’faces’’. He represented himself as an exalted ruler concerning his private dedications and architecture, ever inching closer to deification, but not taking that final step. His deification was to be post mortem. Concerning diplomacy between him and the poleis, he adopted a realpolitik approach, allowing for much self-governance in return for accepting his authority. Maussollos strongly continued the dynastic image set up by his father Hekatomnos concerning the importance of Zeus Labraundos and his Sanctuary at Labraunda, turning the Sanctuary into the major Karian sanctuary. This dynastic parallel can also be seen concerning Hekatomnos’s and Maussollos’s burials, with both being buried as oikistes in terraced tombs, both the inner sanctums depicting Totenmahl-motifs and both being deified after death. Hekatomnos introduced coinage featuring Zeus Labraundos wielding a spear, representing spear- won land. Maussollos adopted this imagery and added Halikarnassian Apollo on the obverse depicting the locations of his two paradeisoi. As for titulature, the Hekatomnids in general eschewed using any which has led to confusion in the ancient sources, but the Hekatomnids were the satraps of Karia, ruling their native land on behalf of the Persian King. -

Assyrian Period (Ca. 1000•fi609 Bce)

CHAPTER 8 The Neo‐Assyrian Period (ca. 1000–609 BCE) Eckart Frahm Introduction This chapter provides a historical sketch of the Neo‐Assyrian period, the era that saw the slow rise of the Assyrian empire as well as its much faster eventual fall.1 When the curtain lifts, at the close of the “Dark Age” that lasted until the middle of the tenth century BCE, the Assyrian state still finds itself in the grip of the massive crisis in the course of which it suffered significant territorial losses. Step by step, however, a number of assertive and ruthless Assyrian kings of the late tenth and ninth centuries manage to reconquer the lost lands and reestablish Assyrian power, especially in the Khabur region. From the late ninth to the mid‐eighth century, Assyria experiences an era of internal fragmentation, with Assyrian kings and high officials, the so‐called “magnates,” competing for power. The accession of Tiglath‐pileser III in 745 BCE marks the end of this period and the beginning of Assyria’s imperial phase. The magnates lose much of their influence, and, during the empire’s heyday, Assyrian monarchs conquer and rule a territory of unprecedented size, including Babylonia, the Levant, and Egypt. The downfall comes within a few years: between 615 and 609 BCE, the allied forces of the Babylonians and Medes defeat and destroy all the major Assyrian cities, bringing Assyria’s political power, and the “Neo‐Assyrian period,” to an end. What follows is a long and shadowy coda to Assyrian history. There is no longer an Assyrian state, but in the ancient Assyrian heartland, especially in the city of Ashur, some of Assyria’s cultural and religious traditions survive for another 800 years. -

Style of Architecture, Consisting of Hard Backed Bricks, Molded in Such a Shape As to Fit Regularly to Each Other”

Journal of Earth Sciences and Geotechnical Engineering, Vol.10, No.3, 2020, 87-111 ISSN: 1792-9040 (print version), 1792-9660 (online) Scientific Press International Limited Babylon in a New Era: The Chaldean and Achaemenid Empires (330-612 BC) Nasrat Adamo1 and Nadhir Al-Ansari2 Abstract The new rise of Babylon is reported and its domination of the old world is described; when two dynasties ruled Neo- Babylonia from 612 BC to 330 BC. First, the Chaldeans had taken over from the Assyrians whom they had defeated and established their empire, which lasted for 77 years followed by the Achaemenid dynasty, which was to rule Babylonia for the remaining period as part of their empire. Out of the 77 years of the Chaldean period king, Nebuchadnezzar II ruled for 43 years, which were full of military achievements and construction works and organization. Apart from extending the borders of the empire, he had managed to construct large-scale hydraulic works which were intended for irrigation, navigation and even for defensive purposes. He excavated, re-excavated, and maintained four large feeder canals taking off from the Euphrates, which served the agriculture in the whole area between the Euphrates and the Tigris in the middle and lower Euphrates regions. Moreover, he was concerned with flood protection and so he constructed one large reservoir near Sippar at 60 km north of Babylon to be filled by the Euphrates excess water during floods and to be returned back to the river during low flow season in summer. His works involved river training projects, so he trained the Euphrates by digging artificial meanders to reduce the velocity of the flow and improving navigation and allow the construction of the canal intakes in a less turbulent flows. -

Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization

oi.uchicago.edu THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION JOHN ALBERT WILSON & THOMAS GEORGE ALLEN - EDITORS ELIZABETH B. HAUSER & RUTH S. BROOKENS • ASSISTANT EDITORS oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu BABYLONIAN CHRONOLOGY 626 B.G.-A.D. 45 oi.uchicago.edu THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS - CHICAGO THE BAKER & TAYLOR COMPANY • NEW YORK THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS • LONDON oi.uchicago.edu BABYLONIAN CHRONOLOGY 626 B.C.-A.D. 45 BT RICHARD A. PARKER AND WALDO H. DUB B ERSTE IX THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION • NO. 24 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS . CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu COPYRIGHT 1942 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PUBLISHED DECEMBER 1942. COMPOSED AND PRINTED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, U.S.A. oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE This study aims at providing a brief, but complete and thorough, presenta tion of the data bearing upon the chronological problems of the Neo-Baby- lonian, Achaemenid Persian, and Seleucid periods, together with tables for the easy translation of dates from the Babylonian calendar into the Julian. Recent additions to our knowledge of intercalary months in the Neo-Baby- lonian and Persian periods have enabled us to improve upon the results of our predecessors in this field, though our great debt to F. X. Kugler and D. Sider- sky for providing the background of our work is obvious. While our tables are intended primarily for historians, both classical and oriental, biblical students also should find them useful, as any biblical date of this period given in the Babylonian calendar can be translated by our tables. -

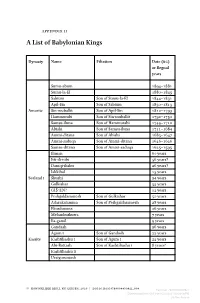

A List of Babylonian Kings

Appendix II A List of Babylonian Kings Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Sumu-abum 1894–1881 Sumu-la-El 1880–1845 Sabium Son of Sumu-la-El 1844–1831 Apil-Sin Son of Sabium 1830–1813 Amorite Sin-muballit Son of Apil-Sin 1812–1793 Hammurabi Son of Sin-muballit 1792–1750 Samsu-iluna Son of Hammurabi 1749–1712 Abishi Son of Samsu-iluna 1711–1684 Ammi-ditana Son of Abishi 1683–1647 Ammi-saduqa Son of Ammi-ditana 1646–1626 Samsu-ditana Son of Ammi-saduqa 1625–1595 Iliman 60 years Itti-ili-nibi 56 years? Damqi-ilishu 26 years? Ishkibal 15 years Sealand I Shushi 24 years Gulkishar 55 years GÍŠ-EN? 12 years Peshgaldaramesh Son of Gulkishar 50 years Adarakalamma Son of Peshgaldaramesh 28 years Ekurduanna 26 years Melamkurkurra 7 years Ea-gamil 9 years Gandash 26 years Agum I Son of Gandash 22 years Kassite Kashtiliashu I Son of Agum I 22 years Abi-Rattash Son of Kashtiliashu I 8 years? Kashtiliashu II Urzigurumash © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_009 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:29:36PM via free access A List of Babylonian Kings 203 Dynasty Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years Harba-Shipak Tiptakzi Agum II Son of Urzigurumash Burnaburiash I […]a Kashtiliashu III Son of Burnaburiash I? Ulamburiash Son of Burnaburiash I? Agum III Son of Kashitiliash IIIb Karaindash Kadashman-Harbe I Kurigalzu I Son of Kadashman-Harbe I Kadashman-Enlil I 1374?–1360 Burnaburiash II Son of Kadashman-Enlil I? 1359–1333 Karahardash Son of Burnaburiash II? 1333 Nazibugash Son of Nobody