John Neagle's Pat Lyon at the Forge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Notebook of Bass Otis, Philadelphia Portrait Painter

The Notebook of Bass Otis, Philadelphia Portrait Painter THOMAS KNOLES INTRODUCTION N 1931, Charles H. Taylor, Jr., gave the American Antiquarian Society a small volume containing notes and sketches made I by Bass Otis (1784-1 S6i).' Taylor, an avid collector of Amer- ican engravings and lithographs who gave thousands of prints to the Society, was likely most interested in Otis as the man generally credited with producing the first lithographs made in America. But to think of Otis primarily in such terms may lead one to under- estimate his scope and productivity as an artist, for Otis worked in a wide variety of media and painted a large number of portraits in the course of a significant career which spanned the period between 1812 and 1861. The small notebook at the Society contains a varied assortment of material with dated entries ranging from 1815 to [H54. It includes scattered names and addresses, notes on a variety of sub- jects, newspaper clippings, sketches for portraits, and even pages on which Otis wiped off his paint brush. However, Otis also used the notebook as an account book, recording there the business side of his life as an artist. These accounts are a uniquely important source of information about Otis's work. Because Otis was a prohfic painter who left many of his works unsigned, his accounts have been I. The notebook is in the Manuscripts Department, American Andquarian Society. THOMAS KNOLES is curator of manuscripts at the American Andquarian Society. Copyright © i<^j3 by American Andquarian Society Í79 Fig. I. Bass Otis (i7«4-iH6i), Self Portrait, iHfio, oil on tin, y'/z x f/i inches. -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art VOLUME I THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C. A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 1 PAINTERS BORN BEFORE 1850 THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C Copyright © 1966 By The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20006 The Board of Trustees of The Corcoran Gallery of Art George E. Hamilton, Jr., President Robert V. Fleming Charles C. Glover, Jr. Corcoran Thorn, Jr. Katherine Morris Hall Frederick M. Bradley David E. Finley Gordon Gray David Lloyd Kreeger William Wilson Corcoran 69.1 A cknowledgments While the need for a catalogue of the collection has been apparent for some time, the preparation of this publication did not actually begin until June, 1965. Since that time a great many individuals and institutions have assisted in com- pleting the information contained herein. It is impossible to mention each indi- vidual and institution who has contributed to this project. But we take particular pleasure in recording our indebtedness to the staffs of the following institutions for their invaluable assistance: The Frick Art Reference Library, The District of Columbia Public Library, The Library of the National Gallery of Art, The Prints and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress. For assistance with particular research problems, and in compiling biographi- cal information on many of the artists included in this volume, special thanks are due to Mrs. Philip W. Amram, Miss Nancy Berman, Mrs. Christopher Bever, Mrs. Carter Burns, Professor Francis W. -

Bass Otis (1784-1861), 1860

BASS OTIS (1784-1861), 1860 self-portrait oil on tin 10 1/8 x 8 1/4 (25.72 x 20.96) inscribed, on verso: ‘Bass Otis/Painted by himself/Aged 76/ for F. J. Dreer, AD 1860’ Gift of Charles Henry Taylor, Jr., 1928 Weis 91 Hewes Number: 91 Ex. Coll.: Ferdinand Julius Dreer (1812-1902); sold at ‘F. J. Dreer’s Collection of Oil Portraits and Engravings,’ auction by Stan T. Henkels, June 6, 1913; purchased by Charles E. Goodspeed for $65; sold to donor. Exhibitions: 1969, ‘A Society’s Chief Joys,’ Grolier Club, New York, no. 212. 1976, ‘Bass Otis: Painter, Portraitist and Engraver,’ Historical Society of Wilmington, Delaware, no. 80. Publications: Wayne Craven and Gainor B. Davis, Bass Otis: Painter, Portraitist and Engraver (Wilmington, Del.: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976), 112. William Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, 3 vols. (Boston: C. E. Goodspeed & Co., 1918), 2: 282. Thomas Knoles, ‘The Notebook of Bass Otis: Philadelphia Portrait Painter,’ Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 103 (April 1993): 180. Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 37 (October 1913): frontispiece. A Society’s Chief Joys (Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1969), 104. That Bass Otis became an artist, specializing in portrait painting, instead of taking up the family trade of scythe-making in the area of Bridgewater, Massachusetts, was a result of following his natural inclination. He learned the basic elements of grinding pigments and mixing colors from a coach maker. He may have studied with Gilbert Stuart in Boston between 1805 and 1808 before moving to New York City, where he may have worked briefly as an assistant to John Wesley Jarvis (1780-1840).1 In 1812 Otis moved to Philadelphia, where his portraits were well-received. -

John Neagle Papers and Related Items 2112 Finding Aid Prepared by Cary Majewicz

John Neagle papers and related items 2112 Finding aid prepared by Cary Majewicz. Last updated on November 09, 2018. First edition Historical Society of Pennsylvania ; 2012 John Neagle papers and related items Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 - Page 2 - John Neagle papers and related items Summary Information Repository Historical Society of Pennsylvania Creator Neagle, John, 1796-1865. Title John Neagle papers and related items Call number 2112 Date 1818-circa 1926, 1990, bulk 1820-1860 -

Paintings and Frescoes

CHAPTER XXI PAINTINGS AND FRESCOES EFORE the commencement of the Capitol extension, the large Westward the Course of Empire takes its Way [Plate 302], by paintings for the panels in the Rotunda were completed, with Emmanuel Leutze, a German artist of prominence, was ordered by one exception. Henry Inman, one of the four artists with General Meigs July 9, 1861, and completed in 1862. The representation whom contracts were made for the historical panels, died of pioneers with their wagons and camping outfits, the mountain BJanuary 17, 1846, without having commenced the painting, although scenery, and Daniel Boone, always attracts the attention of visitors. The he had received $6,000 on account for the work. March 3, 1847, a method of applying the paint to the wall adopted in this painting has contract was made with W. H. Powell to paint the vacant panel. It was been used only in this one instance in the Capitol. The basis is a thin not placed in the Rotunda until 1855. This panel, The Discovery of the layer of cement of powdered marble, quartz, dolomite, and air-worn Mississippi [Plate 299], is intended to depict De Soto and his small lime. The water colors are applied on this cement and fixed by a spray band of followers, the first Caucasians to see our mighty Mississippi. It of water-glass solution. By the method employed it is much easier to is a spirited composition, in no sense realistic, idealizing both make corrections in the painting than with ordinary fresco work. Spaniards and Indians. The Battle on Lake Erie [Plate 301], by W. -

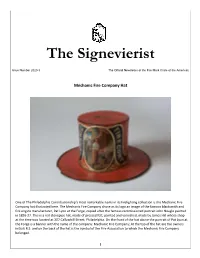

The Signevierist

The Signevierist Issue Number 2020-3 The Official Newsletter of the Fire Mark Circle of the Americas ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Mechanic Fire Company Hat One of The Philadelphia Contributionship’s most remarkable items in its firefighting collection is the Mechanic Fire Company hat illustrated here. The Mechanic Fire Company chose as its logo an image of the famous blacksmith and fire engine manufacturer, Pat Lyon at the Forge, copied after the famous commissioned portrait John Neagle painted in 1826-27. This is a red stovepipe hat, made of pressed felt, painted and varnished, made by James Hill whose shop at the time was located at 207 Callowhill Street, Philadelphia. On the front of the hat above the portrait of Pat Lyon at the Forge is a banner with the name of the company: Mechanic Fire Company; At the top of the hat are the owners initials R.S. and on the back of the hat is the symbol of the Fire Association to which the Mechanic Fire Company belonged. 1 This hat tells different stories: that of the fire engine manufacturer and unjustly accused robber of the Bank of Pennsylvania, and the hat’s owner, R. Sparks, mortally wounded in the Battle of Gettysburg. In 1798 Patrick Lyon was a well-established blacksmith working in Philadelphia having emigrated from Edinburgh Scotland in 1793 and working under the tutelage of Samuel Wheeler, a respected Philadelphia iron worker whose gates can still be seen at Christ Church, before setting up his own business. Lyon had previously learned the craft in London. Although he finished with formal education by age 11, he was interested in mathematics, philosophy and astronomy. -

Armstrong, James, 314 Armstrong, Jane

INDEX (Family names of value in genealogical research are printed in CAPITALS; names of places in italics) Abbott, Benjamin, a follower of Rev- America, Ship bringing German emi- erend George Whitefield, visits War- grants to America, 83, 87 wick iron plantation, 126; quoted, American Antiquarian Society, liter- 126 ary work of John Bach McMaster Abrams, Ray H., The Jeffersonian, at, 9, 15, 23 Copperhead Newspaper, by, 260 American Brasidas, General George Academy of Music, Philadelphia, 364, Gordon Meade, 152 365 American Colkitto, The, by Isaac R. Accident in Lombard Street, Philadel- Pennypacker, 138; General Philip phia, engraved by C. W. Peale, 285 H. Sheridan named American Col- Acrelius, Israel, author, 123, 131, 132 ; kitto, 152 Minister at Christiana, Delaware, American Historical Association, John. 132 ; visits Pennsylvania iron plan- Bach McMaster, President of, 1904- tations, 132 5, 23 Acton, Lord, 19 American Philosophical Society, 24, 55, 198; date of founding, 54; Adams, John, 21 collection of Charles Willson Peale Adams, Samuel, 13S removed to, 174 Addison, Joseph, 194 American Republican, published at Age, The, newspaper, 281 West Chester, 260 Agnew, Doctor D. Hayes, 42, 43, 53 Amusement Gardens in Philadelphia, Agricultural Societies in Pennsylvania, 289-298 124 Anderson, Arnold, 286 Albany, New York, Abraham Lincoln Andrews, Benjamin, William Bar- at, 266; contributions from, for tram visits, 200 Johnstown Flood Relief, 346 Annapolis, Maryland, 162, 163, 348; Alexander the Great, Military leader- St. Ann's Parish of, -

Special Exhibitions Photograph Collection PC.01.06

Special Exhibitions photograph collection PC.01.06 Finding Aid prepared by Hoang Tran The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts 118-128 North Broad Street Philadelphia, PA 19102 [email protected] 215-972-2066 Updated December 2015 Special Exhibitions photograph collection (PC.01.06) Summary Information Repository The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Dorothy and Kenneth Woodcock Archives Creator Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Title Special Exhibitions photograph collection Date [bulk] Date [inclusive] 1893-2010 Extent 18 document boxes Location note Language English Language of Materials note English Abstract Comprehensive collection of photographs of PAFA’s Special Exhibitions, 1893-2010. Photographs are primarily black and white prints but also include transparencies, slides, glass negatives, and compact discs. Preferred Citation note [identification of item], Title of Collection, Collection ID#, The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Dorothy and Kenneth Woodcock Archives, Philadelphia, PA. Page 1 Special Exhibitions photograph collection (PC.01.06) Historical note The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts has sponsored or organized hundreds of special format, thematic, or single-artist exhibitions, large and small, and continues to do so. This category includes traveling exhibitions organized by other museums and, in modern times, thematic exhibitions of the permanent collection. A complete list of special exhibition titles, with additional explanatory material, is available on the Academy website. Volume 1 of The Annual Exhibition Record provides an index to individual artists in most of the pre-1870 special exhibitions. Documentation for special exhibitions ranges from as little as a single printed ticket to full scholarly catalogues. Installation photographs survive in limited numbers from 1894 to 1959 and extensively after that date. -

Henry Clay Calendar

September “Capturing Henry Clay: Through A Year of the Days of His Life” Completed Over the Year 2013 by Charlie Muntz Ashland Docent Henry Clay’s achievements are memorialized across this country, as well as Latin America. And though he has been physically gone for over 161 years, he very much exists in Lexington, Washington, D.C., and a myriad of other notable locales where he made history. Clay residue will be among the last vestiges of our civilization. He was a “Rock Star” of his time, and his story continues to flourish due to the potency of his charismatic persona. He was a “major player” rendering “Ashland” as a mecca for those impressed by power. Speaker of the House, Secretary of State, one of the five most outstanding U.S. Senators, and formulator of three great compromises that held off the Civil War for forty years – all part of his amazing resume. But he was also a husband, father, grandfather, and a key citizen of the Lexington community. He practiced law, farmed, and assembled an “international conclave” of prized livestock at his beloved “Ashland.” The days of his life were filled with varied experiences, extraordinary achievements, worshipful adoration, and the stimulation of travel. There were great highs, but also great disappointments and tragedies. Seven of his children died in his lifetime, and he was often not physically well. He felt the pain of failure five times in his quest to be President, but as Lincoln so admired, was driven by an “implacable will.” This project strives to show the many facets of Henry Clay, through a year of illustrative events and ordinary days covering the better part of his life. -

Pat Lyon at the Forge: Portrait of an American Blacksmith

Pat Lyon at the Forge: Portrait of an American Blacksmith Brigitte Weinsteiger Penn State University Center for Medieval Studies John Neagle’s Pat Lyon at the Forge; 1826-1827; Oil on canvas; 93” x 68” Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Herman and Zoe Oliver Sherman Fund Introduction The portrait of Pat Lyon by the artist, John Neagle, revolutionized the realm of American portraiture. It is the first known portrait depicting a laborer at work. Pat Lyon’s personal story, the social climate of early America, and his pride in being a working blacksmith formed the basis of his choice to be portrayed in this way. Pat Lyon at the Forge demonstrates not only a new style of painting and subject, but also a new attitude towards the laborer and his place in society. Early American Portraiture American portraiture, in the decades following the revolution, documents for us a history of the burgeoning nation’s attitudes and ideals. While we see continuation of the artistic styles of the Old World, there is preference for New World content. An increasingly flourishing middle class fed the American portrait market through its early colonial days in the seventeenth century through to the nineteenth, where it successfully competed with the new genres of landscape and still life, yet still managed to maintain an approximately 90% majority of all paintings commissioned.1 From the onset of portrait-painting in the American colonies at the end of the seventeenth century, there was already a continuation of the styles of Europe. The period, dominated by American artists such as Charles Willson Peale and Ralph Earl, is strikingly reminiscent of European artistic taste, albeit one of a preceding generation. -

Henry Clay and the American State Portrait Clifford Amyx University of Kentucky

The Kentucky Review Volume 10 | Number 3 Article 4 Fall 1990 Henry Clay and the American State Portrait Clifford Amyx University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Amyx, Clifford (1990) "Henry Clay and the American State Portrait," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 10 : No. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol10/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Henry Clay and the American State Portrait Clifford Amyx America, having rejected royalty and established a republic, was obliged to create a state portrait without royalist trappings. In fact, when Pres. Andrew Jackson was accused of exercising unwarranted executive power he was caricatured with precisely the most familiar of the royalist attributes-the ermine robe, the sceptre of power, and the crown. American painters, seeking to create a sense of authority in the portraits of their statesmen, retained from Europe two of the basic attributes of formal or stately presence, the flowing heavy drape familiar in Baroque court portraits, and the classical column with its connotation of a formal or stately milieu. These attributes were familiar to the American artists who learned their art in England. -

Andrew Jackson (1767–1845)

Andrew Jackson (1767–1845) Andrew Jackson was a national hero for his n 1824 Thomas Sully painted a study portrait from life of Andrew defeat of the British at New Orleans in the Jackson. The hero of the Battle of New Orleans was by then a War of 1812. He was born in what is today Lancaster County, South Carolina, U.S. senator and a Democratic nominee for president. Two decades and later moved to what is now Nashville, later, Jackson’s ill health prompted Sully to copy his 1824 study Tennessee. In 1796, after serving as a dele- portrait; the replica, which closely resembles the study, was com gate to Tennessee’s first Constitutional Con pleted shortly before Jackson’s death in April 1845. It is now owned by vention, Jackson was the first person elected I to the U.S. House of Representatives from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Sully used the replica as the state of Tennessee. The following year, a model to create a full-length portrait of Jackson as the battle hero (this he won a seat in the U.S. Senate but soon resigned for personal and financial reasons. painting is now owned by the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, From 1798 to 1804 he served as a supe- D.C.). The National Gallery’s portrait was long assumed to be the orig rior court judge in Tennessee, then retired to inal 1824 life study until it was discovered that the artist had not purchased live the life of a country gentleman.