Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Art Related Letters from Historical Society of Pennsylvania's Society Collection

Selected art related letters from Historical Society of Pennsylvania's Society Collection Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Selected art related letters from Historical Society of Pennsylvania's Society Collection AAA.histsopa Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Selected art related letters from Historical Society of Pennsylvania's Society Collection Identifier: AAA.histsopa Date: 1760-1935 -

The Notebook of Bass Otis, Philadelphia Portrait Painter

The Notebook of Bass Otis, Philadelphia Portrait Painter THOMAS KNOLES INTRODUCTION N 1931, Charles H. Taylor, Jr., gave the American Antiquarian Society a small volume containing notes and sketches made I by Bass Otis (1784-1 S6i).' Taylor, an avid collector of Amer- ican engravings and lithographs who gave thousands of prints to the Society, was likely most interested in Otis as the man generally credited with producing the first lithographs made in America. But to think of Otis primarily in such terms may lead one to under- estimate his scope and productivity as an artist, for Otis worked in a wide variety of media and painted a large number of portraits in the course of a significant career which spanned the period between 1812 and 1861. The small notebook at the Society contains a varied assortment of material with dated entries ranging from 1815 to [H54. It includes scattered names and addresses, notes on a variety of sub- jects, newspaper clippings, sketches for portraits, and even pages on which Otis wiped off his paint brush. However, Otis also used the notebook as an account book, recording there the business side of his life as an artist. These accounts are a uniquely important source of information about Otis's work. Because Otis was a prohfic painter who left many of his works unsigned, his accounts have been I. The notebook is in the Manuscripts Department, American Andquarian Society. THOMAS KNOLES is curator of manuscripts at the American Andquarian Society. Copyright © i<^j3 by American Andquarian Society Í79 Fig. I. Bass Otis (i7«4-iH6i), Self Portrait, iHfio, oil on tin, y'/z x f/i inches. -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art VOLUME I THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C. A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 1 PAINTERS BORN BEFORE 1850 THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C Copyright © 1966 By The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20006 The Board of Trustees of The Corcoran Gallery of Art George E. Hamilton, Jr., President Robert V. Fleming Charles C. Glover, Jr. Corcoran Thorn, Jr. Katherine Morris Hall Frederick M. Bradley David E. Finley Gordon Gray David Lloyd Kreeger William Wilson Corcoran 69.1 A cknowledgments While the need for a catalogue of the collection has been apparent for some time, the preparation of this publication did not actually begin until June, 1965. Since that time a great many individuals and institutions have assisted in com- pleting the information contained herein. It is impossible to mention each indi- vidual and institution who has contributed to this project. But we take particular pleasure in recording our indebtedness to the staffs of the following institutions for their invaluable assistance: The Frick Art Reference Library, The District of Columbia Public Library, The Library of the National Gallery of Art, The Prints and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress. For assistance with particular research problems, and in compiling biographi- cal information on many of the artists included in this volume, special thanks are due to Mrs. Philip W. Amram, Miss Nancy Berman, Mrs. Christopher Bever, Mrs. Carter Burns, Professor Francis W. -

Flow Blue Continues to Dazzle Buyers by Barbara Miller Beem Purposeful One

Evans Winter auction will make a GTO at Stevens turned it on, splash wound it up and blew it out $1.50 National p. 1 National p. 1 AntiqueWeekHE EEKLY N T IQUE A UC T ION & C OLLEC T ING N E W SP A PER T W A E A S T ERN E DI T ION VOL. 52 ISSUE NO. 2627 www.antiqueweek.com FEBRUARY 3, 2020 Above Left: “Savoy” by Johnson Brothers (1900). This distinctive dinnerware presents four-leaf clovers set in oval medallions. The center clover is set in grill work. Courtesy of Flow Blue International Collectors Club. Above Middle: “Hanley” by G.L. Ashworth & Bros. (1860). A border-only pattern, this plate is representative of the Mid-Victorian Period. Courtesy of Flow Blue International Collectors Club. Above Right: “Viola” by Wood & Baggaley (1875). The patterns on flow blue china from the Mid-Victorian Period are not as heavily flown, perhaps due to refinements in the chemical process during the firing. Courtesy of Flow Blue International Collectors Club Flow blue continues to dazzle buyers By Barbara Miller Beem purposeful one. “But it’s more romantic to say it was accidental,” according to Julie Robbins, a product specialist at Replacements, Ltd. She suggested that if When it comes to flow blue china, unanswerable questions continue to swirl these lovely pieces of pottery were produced by chance, the process would most about: Who perfected the technique to blur out the cobalt blue decorations? How likely have been lost by now. was the exact mixture of chemicals formulated, and how many failed attempts As for that process, W.P. -

“The Humble, Though More Profitable Art”

“THE HUMBLE, THOUGH MORE PROFITABLE ART”: PANORAMIC SPECTACLES IN THE AMERICAN ENTERTAINMENT WORLD, 1794- 1850 by Nalleli Guillen A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Spring 2018 © 2018 Nalleli Guillen All Rights Reserved “THE HUMBLE, THOUGH MORE PROFITABLE ART”: PANORAMIC SPECTACLES IN THE AMERICAN ENTERTAINMENT WORLD, 1794- 1850 by Nalleli Guillen Approved: __________________________________________________________ Arwen P. Mohun, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of History Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Katherine C. Grier, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Rebecca L. Davis, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ David Suisman, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

Bass Otis (1784-1861), 1860

BASS OTIS (1784-1861), 1860 self-portrait oil on tin 10 1/8 x 8 1/4 (25.72 x 20.96) inscribed, on verso: ‘Bass Otis/Painted by himself/Aged 76/ for F. J. Dreer, AD 1860’ Gift of Charles Henry Taylor, Jr., 1928 Weis 91 Hewes Number: 91 Ex. Coll.: Ferdinand Julius Dreer (1812-1902); sold at ‘F. J. Dreer’s Collection of Oil Portraits and Engravings,’ auction by Stan T. Henkels, June 6, 1913; purchased by Charles E. Goodspeed for $65; sold to donor. Exhibitions: 1969, ‘A Society’s Chief Joys,’ Grolier Club, New York, no. 212. 1976, ‘Bass Otis: Painter, Portraitist and Engraver,’ Historical Society of Wilmington, Delaware, no. 80. Publications: Wayne Craven and Gainor B. Davis, Bass Otis: Painter, Portraitist and Engraver (Wilmington, Del.: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976), 112. William Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, 3 vols. (Boston: C. E. Goodspeed & Co., 1918), 2: 282. Thomas Knoles, ‘The Notebook of Bass Otis: Philadelphia Portrait Painter,’ Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 103 (April 1993): 180. Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 37 (October 1913): frontispiece. A Society’s Chief Joys (Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1969), 104. That Bass Otis became an artist, specializing in portrait painting, instead of taking up the family trade of scythe-making in the area of Bridgewater, Massachusetts, was a result of following his natural inclination. He learned the basic elements of grinding pigments and mixing colors from a coach maker. He may have studied with Gilbert Stuart in Boston between 1805 and 1808 before moving to New York City, where he may have worked briefly as an assistant to John Wesley Jarvis (1780-1840).1 In 1812 Otis moved to Philadelphia, where his portraits were well-received. -

John Neagle Papers and Related Items 2112 Finding Aid Prepared by Cary Majewicz

John Neagle papers and related items 2112 Finding aid prepared by Cary Majewicz. Last updated on November 09, 2018. First edition Historical Society of Pennsylvania ; 2012 John Neagle papers and related items Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 - Page 2 - John Neagle papers and related items Summary Information Repository Historical Society of Pennsylvania Creator Neagle, John, 1796-1865. Title John Neagle papers and related items Call number 2112 Date 1818-circa 1926, 1990, bulk 1820-1860 -

Paintings and Frescoes

CHAPTER XXI PAINTINGS AND FRESCOES EFORE the commencement of the Capitol extension, the large Westward the Course of Empire takes its Way [Plate 302], by paintings for the panels in the Rotunda were completed, with Emmanuel Leutze, a German artist of prominence, was ordered by one exception. Henry Inman, one of the four artists with General Meigs July 9, 1861, and completed in 1862. The representation whom contracts were made for the historical panels, died of pioneers with their wagons and camping outfits, the mountain BJanuary 17, 1846, without having commenced the painting, although scenery, and Daniel Boone, always attracts the attention of visitors. The he had received $6,000 on account for the work. March 3, 1847, a method of applying the paint to the wall adopted in this painting has contract was made with W. H. Powell to paint the vacant panel. It was been used only in this one instance in the Capitol. The basis is a thin not placed in the Rotunda until 1855. This panel, The Discovery of the layer of cement of powdered marble, quartz, dolomite, and air-worn Mississippi [Plate 299], is intended to depict De Soto and his small lime. The water colors are applied on this cement and fixed by a spray band of followers, the first Caucasians to see our mighty Mississippi. It of water-glass solution. By the method employed it is much easier to is a spirited composition, in no sense realistic, idealizing both make corrections in the painting than with ordinary fresco work. Spaniards and Indians. The Battle on Lake Erie [Plate 301], by W. -

John Neagle's Pat Lyon at the Forge

Bass Otis’ Interior of a Smithy; c. 1815; Oil on canvas; 50½” x 80½” Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts; Gift of the artist Art in the New World: the Glorified Laborer A painting of such content had never before been seen in either the Old or the New World. How was it possible for such a young artist to paint such an extraordinary subject? The answer to this question lies in the new nation’s perception of itself and its newfound ideals. The young country had just fought a war both for equality, where laborers were considered equal to gentlemen, and in support of a fair government with an egalitarian judicial system. Lyon’s story embodied both of these principles. Not only did he represent the “American” ideal of starting from nothing and making something of oneself, but he also vindicated the new American political system. Judge Yates, the judge assigned to Lyon’s trial, stated in his last charge to the jury, “… the tradesman who depends upon his labor for his existence, is to be regarded as much as any other member of the community, Wealth and respectability of character should not weigh as a feather in the scale, when another man’s rights are violated. It is unquestionably time, that in our country at least, we stand up on the rights of man, neither wealth nor office create an unequal standing, or give to any man a superiority over his fellow citizens.”1 This novel outlook on laborers was also in large part due to the machinations of Benjamin Franklin. -

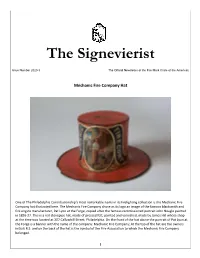

The Signevierist

The Signevierist Issue Number 2020-3 The Official Newsletter of the Fire Mark Circle of the Americas ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Mechanic Fire Company Hat One of The Philadelphia Contributionship’s most remarkable items in its firefighting collection is the Mechanic Fire Company hat illustrated here. The Mechanic Fire Company chose as its logo an image of the famous blacksmith and fire engine manufacturer, Pat Lyon at the Forge, copied after the famous commissioned portrait John Neagle painted in 1826-27. This is a red stovepipe hat, made of pressed felt, painted and varnished, made by James Hill whose shop at the time was located at 207 Callowhill Street, Philadelphia. On the front of the hat above the portrait of Pat Lyon at the Forge is a banner with the name of the company: Mechanic Fire Company; At the top of the hat are the owners initials R.S. and on the back of the hat is the symbol of the Fire Association to which the Mechanic Fire Company belonged. 1 This hat tells different stories: that of the fire engine manufacturer and unjustly accused robber of the Bank of Pennsylvania, and the hat’s owner, R. Sparks, mortally wounded in the Battle of Gettysburg. In 1798 Patrick Lyon was a well-established blacksmith working in Philadelphia having emigrated from Edinburgh Scotland in 1793 and working under the tutelage of Samuel Wheeler, a respected Philadelphia iron worker whose gates can still be seen at Christ Church, before setting up his own business. Lyon had previously learned the craft in London. Although he finished with formal education by age 11, he was interested in mathematics, philosophy and astronomy. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 304 351 SO 019 E31 TITLE Historic

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 304 351 SO 019 E31 TITLE Historic Pennsylvania Leaflets No. 1-41. 1960-1988. INSTITUTION Pennsylvania State Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 166p.; Leaflet No. 16, not included here, is out of print. Published during various years from 1960-1988. AVAILABLE FROMPennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, P.O. Box 1026, Harrisburg, PA 17108 ($4.00). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020)-- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS History; Pamphlets; *Social Studies; *State History IDENTIFIERS History al Explanation; *Historical Materials; *Pennsylvania ABSTRACT This series of 41 pamphlets on selected Pennsylvania history topics includes: (1) "The PennsylvaniaCanals"; (2) "Anthony Wayne: Man of Action"; (3) "Stephen Foster: Makerof American Songs"; (4) "The Pennsylvania Rifle"; (5) "TheConestoga Wagon"; (6) "The Fight for Free Schools in Pennsylvania"; (7) "ThaddeusStevens: Champion of Freedom"; (8) "Pennsylvania's State Housesand Capitols"; (9) "Harrisburg: Pennsylvania's Capital City"; (10)"Pennsylvania and the Federal Constitution"; (11) "A French Asylumon the Susquehanna River"; (12) "The Amish in American Culture"; (13)"Young Washington in Pennsylvania"; (14) "Ole Bull's New Norway"; (15)"Henry BoLquet and Pennsylvania"; (16)(out of print); (17) "Armstrong's Victoryat Kittanning"; (18) "Benjamin Franklin"; (19) "The AlleghenyPortage Railroad"; (20) "Abraham Lincoln and Pennsylvania"; (21)"Edwin L. Drake and the Birth of the -

Armstrong, James, 314 Armstrong, Jane

INDEX (Family names of value in genealogical research are printed in CAPITALS; names of places in italics) Abbott, Benjamin, a follower of Rev- America, Ship bringing German emi- erend George Whitefield, visits War- grants to America, 83, 87 wick iron plantation, 126; quoted, American Antiquarian Society, liter- 126 ary work of John Bach McMaster Abrams, Ray H., The Jeffersonian, at, 9, 15, 23 Copperhead Newspaper, by, 260 American Brasidas, General George Academy of Music, Philadelphia, 364, Gordon Meade, 152 365 American Colkitto, The, by Isaac R. Accident in Lombard Street, Philadel- Pennypacker, 138; General Philip phia, engraved by C. W. Peale, 285 H. Sheridan named American Col- Acrelius, Israel, author, 123, 131, 132 ; kitto, 152 Minister at Christiana, Delaware, American Historical Association, John. 132 ; visits Pennsylvania iron plan- Bach McMaster, President of, 1904- tations, 132 5, 23 Acton, Lord, 19 American Philosophical Society, 24, 55, 198; date of founding, 54; Adams, John, 21 collection of Charles Willson Peale Adams, Samuel, 13S removed to, 174 Addison, Joseph, 194 American Republican, published at Age, The, newspaper, 281 West Chester, 260 Agnew, Doctor D. Hayes, 42, 43, 53 Amusement Gardens in Philadelphia, Agricultural Societies in Pennsylvania, 289-298 124 Anderson, Arnold, 286 Albany, New York, Abraham Lincoln Andrews, Benjamin, William Bar- at, 266; contributions from, for tram visits, 200 Johnstown Flood Relief, 346 Annapolis, Maryland, 162, 163, 348; Alexander the Great, Military leader- St. Ann's Parish of,