“The Humble, Though More Profitable Art”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Art Related Letters from Historical Society of Pennsylvania's Society Collection

Selected art related letters from Historical Society of Pennsylvania's Society Collection Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Selected art related letters from Historical Society of Pennsylvania's Society Collection AAA.histsopa Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Selected art related letters from Historical Society of Pennsylvania's Society Collection Identifier: AAA.histsopa Date: 1760-1935 -

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters Collection MC.100

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection MC.100 Last updated on January 06, 2021. Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................7 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 110.American poets................................................................................................................................. 9 115.British poets.................................................................................................................................... 16 120.Dramatists........................................................................................................................................23 130.American prose writers...................................................................................................................25 135.British Prose Writers...................................................................................................................... 33 140.American -

Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: a Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1993 Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: A Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons John Patrick Fitzgibbons Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Fitzgibbons, John Patrick, "Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: A Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons" (1993). Dissertations. 3283. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3283 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1993 John Patrick Fitzgibbons Theodore Parker's Man-Making Strategy: A Study of His Professional Ministry in Selected Sermons by John Patrick Fitzgibbons, S.J. A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Chicago, Illinois May, 1993 Copyright, '°1993, John Patrick Fitzgibbons, S.J. All rights reserved. PREFACE Theodore Parker (1810-1860) fashioned a strategy of "man-making" and an ideology of manhood in response to the marginalization of the professional ministry in general and his own ministry in particular. Much has been written about Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) and his abandonment of the professional ministry for a literary career after 1832. Little, however, has been written about Parker's deliberate choice to remain in the ministry despite formidable opposition from within the ranks of Boston's liberal clergy. -

Passing Through: the Allure of the White Mountains

Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains The White Mountains presented nineteenth- century travelers with an American landscape: tamed and welcoming areas surrounded by raw and often terrifying wilderness. Drawn by the natural beauty of the area as well as geologic, botanical, and cultural curiosities, the wealthy began touring the area, seeking the sublime and inspiring. By the 1830s, many small-town tav- erns and rural farmers began lodging the new travelers as a way to make ends meet. Gradually, profit-minded entrepreneurs opened larger hotels with better facilities. The White Moun- tains became a mecca for the elite. The less well-to-do were able to join the elite after midcentury, thanks to the arrival of the railroad and an increase in the number of more affordable accommodations. The White Moun- tains, close to large East Coast populations, were alluringly beautiful. After the Civil War, a cascade of tourists from the lower-middle class to the upper class began choosing the moun- tains as their destination. A new style of travel developed as the middle-class tourists sought amusement and recreation in a packaged form. This group of travelers was used to working and commuting by the clock. Travel became more time-oriented, space-specific, and democratic. The speed of train travel, the increased numbers of guests, and a widening variety of accommodations opened the White Moun- tains to larger groups of people. As the nation turned its collective eyes west or focused on Passing Through: the benefits of industrialization, the White Mountains provided a nearby and increasingly accessible escape from the multiplying pressures The Allure of the White Mountains of modern life, but with urban comforts and amenities. -

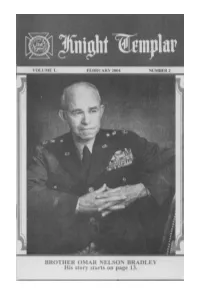

Knight Templar Magazine

Grand Master's Message for February 2004 February brings many pleasant and yet poignant memories. It is, of course, the month in which we remember those dear to us with Valentine's Day (another day of love). We are so fortunate to have those ladies in our lives who have done so much for us; our wives, mothers, sisters, daughters, etc. Speaking for the Sir Knights, we do appreciate everything that you have done for us. Many of our ladies are members of the Social Order of the Beauceant, which has raised tens of thousands of dollars, annually, for the Knights Templar Eye Foundation. Some states do not have the S.O.O.B. but do have ladies' auxiliaries, which also help their Commanderies and the Eye Foundation. Sir Knights, be sure that you recognize and thank your ladies. Some roses, candy, or whatever makes her happy would be good. She will probably wonder, what the devil you have been doing to cause you to take this action, but the net result should be good. This February is in a "Leap Year," which reminds me of a dear aunt who was born on February 29. When she passed away, she had celebrated 21 birthdays. She was my mother's next older sister and was a true workaholic. She loved to fish and would catch fish no matter what it took to catch them. Happy Birthday, Aunt Lenora! Another February memory was the tradition at our house of pruning our rose bushes on or around Valentine's Day. This was at a time when the bush was dormant and pruning would have the best effect on the bush as it came to life and began growing again in the spring. -

Bible Matters: the Scriptural Origins of American Unitarianism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Vanderbilt Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Archive BIBLE MATTERS: THE SCRIPTURAL ORIGINS OF AMERICAN UNITARIANISM By LYDIA WILLSKY Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In Religion May, 2013 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor James P. Byrd Professor James Hudnut-Beumler Professor Kathleen Flake Professor Paul Lim Professor Paul Conkin TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………3 CHAPTER 1: WILLIAM ELLERY CHANNING AND THE PASTORAL ROOTS OF UNITARIAN BIBLICISM………………………………………………………………………………..29 CHAPTER 2: WHAT’S “GOSPEL” IN THE BIBLE? ANDREWS NORTON AND THE LANGUAGE OF BIBLICAL TRUTH………………………………………...................................................77 CHAPTER 3: A PRACTICAL SPIRIT: FREDERIC HENRY HEDGE, THE BIBLE AND THE UNIVERSAL CHURCH…………………………………………………………………...124 CHAPTER 4: THE OPENING OF THE CANON: THEODORE PARKER AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF BIBLICAL AUTHORITY…………………………………………..168 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………...........................205 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………………213 INTRODUCTION The New England Unitarians were a biblical people. They were not biblical in the way of their Puritan ancestors, who emulated the early apostolic Church and treated the Bible as a model for right living. They were a biblical people in the way almost every Protestant denomination of the nineteenth century -

Download Download

TEMPERANCE, ABOLITION, OH MY!: JAMES GOODWYN CLONNEY’S PROBLEMS WITH PAINTING THE FOURTH OF JULY Erika Schneider Framingham State College n 1839, James Goodwyn Clonney (1812–1867) began work on a large-scale, multi-figure composition, Militia Training (originally Ititled Fourth of July ), destined to be the most ambitious piece of his career [ Figure 1 ]. British-born and recently naturalized as an American citizen, Clonney wanted the American art world to consider him a major artist, and he chose a subject replete with American tradition and patriotism. Examining the numer- ous preparatory sketches for the painting reveals that Clonney changed key figures from Caucasian to African American—both to make the work more typically American and to exploit the popular humor of the stereotypes. However, critics found fault with the subject’s overall lack of decorum, tellingly with the drunken behavior and not with the African American stereotypes. The Fourth of July had increasingly become a problematic holi- day for many influential political forces such as temperance and abolitionist groups. Perhaps reflecting some of these pressures, when the image was engraved in 1843, the title changed to Militia Training , the title it is known by today. This essay will pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 77, no. 3, 2010. Copyright © 2010 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 14:57:03 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PAH77.3_02Schneider.indd 303 6/29/10 11:00:40 AM pennsylvania history demonstrate how Clonney reflected his time period, attempted to pander to the public, yet failed to achieve critical success. -

Portraits by Gilbert Stuart

PORTRAITS BY JUNE 29 TO AUGUST l • 1936 AT THE GALLERIES OF M. KNOEDLER & COMPANY NEWPORT RHODE ISLAND As A contribution to the Newport Tercentenary observation we feel that in no way can we make a more fitting offering than by holding an exhibition of paintings by Gilbert Stuart. Nar- ragansett was the birthplace and boyhood home of America's greatest artist and a Newport celebration would be grievously lacking which did not contain recognition of this. In arranging this important exhibition no effort has been made to give a chronological nor yet an historical survey of Stuart's portraits, rather have we aimed to show a collection of paintings which exemplifies the strength as well as the charm and grace of Stuart's work. This has required that we include portraits he painted in Ireland and England as well as those done in America. His place will always stand among the great portrait painters of the world. 1 GEORGE WASHINGTON Canvas, 25 x 30 inches. Painted, 1795. This portrait of George Washington, showing the right side of the face is known as the Vaughan type, so called for the owner of the first of the type, in contradistinction to the Athenaeum portrait depicting the left side of the face. Park catalogues fifteen of the Vaughan por traits and seventy-four of the Athenaeum portraits. "Philadelphia, 1795. Canvas, 30 x 25 inches. Bust, showing the right side of the face; powdered hair, black coat, white neckcloth and linen shirt ruffle. The background is plain and of a soft crimson and ma roon color. -

Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn

'Memorials of great & good men who were my friends'': Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn ELLEN G. MILES LIVER woLCOTT, JR. (1760-1833), like many of his contemporaries, used portraits as familial icons, as ges- Otures in political alliances, and as public tributes and memorials. Wolcott and his father Oliver Wolcott, Sr. (i 726-97), were prominent in Connecticut politics during the last quarter of the eighteenth century and the first quarter of the nineteenth. Both men served as governors of the state. Wolcott, Jr., also served in the federal administrations of George Washington and John Adams. Withdrawing from national politics in 1800, he moved to New York City and was a successful merchant and banker until 1815. He spent the last twelve years of his public life in Con- I am grateful for a grant from the Smithsonian Institution's Research Opportunities Fund, which made it possible to consult manuscripts and see portraits in collecdüns in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, New Haven, î lartford. and Litchfield (Connecticut). Far assistance on these trips I would like to thank Robin Frank of the Yale Universit)' Art Gallery, .'\nne K. Bentley of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Judith Ellen Johnson and Richard Malley of the Connecticut Historical Society, as well as the society's fonner curator Elizabeth Fox, and Elizabeth M. Komhauscr, chief curator at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford. David Spencer, a former Smithsonian Institution Libraries staff member, gen- erously assisted me with the VVolcott-Cibbs Family Papers in the Special Collectiims of the University of Oregon Library, Eugene; and tht staffs of the Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Ciallery, and the Inventory of American Painting. -

David Mccullough

A teacher’s guide to DAVID C ULLOUGH M C WINNER OF THE PULITZER PRIZE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 About the Author 1 Resources 1 Key Figures 2 Pre-Reading Knowledge 5 Part I, Chapter 1 6 Part I, Chapter 2 8 Part I, Chapter 3 11 Part II, Chapter 4 14 Part II, Chapter 5 17 Part III, Chapter 6 19 Part III, Chapter 7 22 INTRODUCTION Although the passage of the Declaration of Independence is a universally taught event in the United States, most high school students’ knowledge tends to be confined to the events that occurred in the city of Philadelphia during the month of July. In focusing on the events throughout the year of 1776, Pulitzer Prize–winning historian David McCullough gives students a deep understanding, from both sides of the conflict, of the events, people, and decisions that led to the creation of the United States. McCullough’s extensively researched work is filled with primary sources, reinforcing details and differing points of view on the events presented within the text, all of which makes 1776 an excellent text for use with the Common Core standards. This teacher’s guide provides a brief summary of 1776, divided by chapter and then subdivided by section. Each section summary includes a list of Key Features. Also provided for each chapter are the following supplementary teaching aids to spur discussion and challenge the student’s knowledge of the material: Key Terms and Vocabulary, Questions, Primary and Alternate Source Analysis, Activities and Projects, and for some chapters, an Interdisciplinary Activity. -

Selected Peale Family Papers

Selected Peale family papers Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Selected Peale family papers AAA.pealpeal Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Selected Peale family papers Identifier: AAA.pealpeal Date: 1803-1854 Creator: Peale family Extent: 3 Microfilm reels (3 partial microfilm reels) Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Microfilmed by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania for the Archives of American Art, 1955. Location of Originals REEL P21: Originals in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Peale family papers. Location of Originals REEL P23, P29: Originals in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, -

Two Discs from Fores's Moving Panorama. Phenakistiscope Discs

Frames per second / Pre-cinema, Cinema, Video / Illustrated catalogue at www.paperbooks.ca/26 01 Fores, Samuel William Two discs from Fores’s moving panorama. London: S. W. Fores, 41 Piccadily, 1833. Two separate discs; with vibrantly-coloured lithographic images on circular card-stock (with diameters of 23 cm.). Both discs featuring two-tier narratives; the first, with festive subject of music and drinking/dancing (with 10 images and 10 apertures), the second featuring a chap in Tam o' shanter, jumping over a ball and performing a jig (with 12 images and 12 apertures). £ 350 each (w/ modern facsimile handle available for additional £ 120) Being some of the earliest pre-cinema devices—most often attributed either to either Joseph Plateau of Belgium or the Austrian Stampfer, circa 1832—phenakistiscopes (sometimes called fantascopes) functioned as indirect media, requiring a mirror through which to view the rotating discs, with the discrete illustrations activated into a singular animation through the interruption-pattern produced by the set of punched apertures. The early discs offered here were issued from the Piccadily premises of Samuel William Fores (1761-1838)—not long after Ackermann first introduced the format into London. Fores had already become prolific in the publishing and marketing of caricatures, and was here trying to leverage his expertise for the newest form of popular entertainment, with his Fores’s moving panorama. 02 Anonymous Phenakistiscope discs. [Germany?], circa 1840s. Four engraved card discs (diameters avg. 18