Passing Through: the Allure of the White Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIA EMAIL Pamela G. Monroe, Administrator New Hampshire Site Evaluation Committee 21 South Fruit Street, Suite Concord, NH 03301-2429

............................................................................................................. VIA EMAIL Pamela G. Monroe, Administrator New Hampshire Site Evaluation Committee 21 South Fruit Street, Suite Concord, NH 03301-2429 January 25, 20016 Re: Joint Application of Northern Pass Transmission, LLC and Public Service Company of New Hampshire d/b/a/ Eversource Energy for a Certificate of Site and Facility (SEC Docket No. 2015-6) – Intervention of the Appalachian Mountain Club Dear Ms. Monroe : Enclosed is the intervention filing for the Appalachian Mountain Club relative to the “Joint Application of Northern Pass Transmission, LLC and Public Service Company of New Hampshire d/b/a/ Eversource Energy for a Certificate of Site and Facility ” before the Site Evaluation Committee (SEC Docket No. 2015-6)”. Copies of this letter and enclosure have of this date been forwarded via email to all parties on the email distribution list. We hereby also request that the following individuals be added to the interested party distribution list on behalf of the Appalachian Mountain Club: (i) Dr. Kenneth Kimball, Director of Research, Appalachian Mountain Club, PO Box 298, Gorham, NH 03581, 603-466-8149, [email protected] , (ii) Aladdine Joroff, Staff Attorney, Emmett Environmental Law & Policy Clinic, Harvard Law School, 6 Everett Street, Suite 4119, Cambridge, MA 02138 617- 495-5014 [email protected] (iii) Wendy B. Jacobs, Clinical Professor and Director of the Emmett Environmental Law and Policy Clinic, Harvard Law School, 6 Everett Street, Suite 4119, Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Main Headquarters : 5 Joy Street • Boston, MA 02108-1490 • 617-523-0636 • outdoors.org Regional Headquarters : Pinkham Notch Visitor Center • 361 Route 16 • Gorham, NH 03581-0298 • 603 466-2721 Additional Offices : Bretton Woods, NH • Greenville, ME • Portland, ME • New York, NY • Bethlehem, PA ............................................................................................................ -

Dry River Wilderness

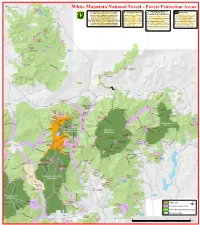

«¬110 SOUTH White Mountain National Forest - Forest Protection Areas POND !5 !B Forest Protection Areas (FPAs) are geographic South !9 Designated Sites !9 The Alpine Zone Wilderness Pond areas where certain activities are restricted to A Rarity in the Northeast Rocky prevent overuse or damage to National Forest Designated sites are campsites or Wilderness Areas are primitive areas Pond resources. Restrictions may include limits on picnic areas within a Forest The alpine zone is a high elevation area in with few signs or other developments. !B camping, use of wood or charcoal fires and Protection area where otherwise which trees are naturally absent or stunted Trails may be rough and difficult to maximum group size. FPAs surround certain features prohibited activities (camping at less that eight feet tall. About 8 square follow. Camping and fires are gererally miles of this habitat exists in the prohibited within 200 feet of any trail W (trails, ponds, parking areas, etc) with either a 200-foot and/or fires) may occur. These e s or ¼ mile buffer. They are marked with signs sites are identified by an official Northeast with most of it over 4000 feet unless at a designated site. No more t M as you enter and exit so keep your eyes peeled. sign, symbol or map. in elevation. Camping is prohibited in the than ten people may occupy a single i la TYPE Name GRID n alpine zone unless there is two or more campsite or hike in the same party. Campgrounds Basin H5 feet of snow. Fires are prohibited at all Big Rock E7 !B Blackberry Crossing G8 ROGERS times. -

Hike Leader Handbook

Excursions Committee New Hampshire Chapter Of the Appalachian Mountain Club Hike Leader Handbook February, 2016 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 2 of 75. 2AMC–NH Chapter Excursions Committee Hike Leader Handbook Table of Contents Letter to New Graduates The Trail to Leadership – Part D Part 1 - Leader Requirements Part 2 – Hike Leader Bill of Rights Part 2a-Leader-Participant Communication Part 3 - Guidelines for Hike Leaders Part 4 - Hike Submission Procedures Part 5 – On-line Hike Entry Instructions (AMC Database) Part 5a – Meetup Posting Instructions Part 6 – Accident & Summary of Use Report Overview Part 7 - AMC Incident Report Form Part 8 - WMNF Use Report Form Part 9 - Excursions Committee Meetings Part 10 - Mentor Program Overview Part 11 – Leader Candidate Requirements Part 12 - Mentor Requirements Part 13 - Mentor Evaluation Form Part 14 - Class 1 & 2 Peaks List Part 15 - Class 3 Peaks List Part 16 - Liability Release Form Instructions Part 17 - Release Form FAQs Part 18 - Release Form Part 19 - Activity Finance Policy Part 20 - Yahoo Group Part 21 – Leadership Recognition Part 22 – Crosswalk between Classes and Committees NH AMC Excursion Committee Bylaws Page 1 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 3 of 75. Page 2 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 4 of 75. Hello, Leadership Class Graduate! We hope that you enjoyed yourself at the workshop, and found the weekend worthwhile. We also hope that you will consider becoming a NH Chapter AMC Hike leader—you’ll be a welcome addition to our roster of leaders, and will have a fun and rewarding experience to boot! About the Excursions Committee: We are the hikers in the New Hampshire Chapter, and we also lead some cycling hikes. -

Object Engraving, by N. and S.S. Jocelyn, 1828 Courtesy of New Hampshire State Library

Object Engraving, by N. and S.S. Jocelyn, 1828 Courtesy of New Hampshire State Library There are several conflicting accounts about the discovery of the Old Man of the Mountain, the earliest known dating from 1844. However, most of the accounts agree that the granite profile was first seen—other than presumably by Native Americans—around 1805 and that it was first noticed by members of a surveying party working and camping in Franconia Notch near Ferrin’s Pond (later renamed Profile Lake) and that just one or two members of the party happened to be in just the right spot, looking in just the right direction to see the remarkable face. In 1828, this engraving based on a sketch by “a gentleman of Boston” is the first known image of the natural profile. It was published in the American Journal of Science and Arts, making the natural wonder more widely known. Object Old Man of the Mountain, by Edward New Hampshire Historical Society Hill, 1879 1925.007.01 The White Mountains tourism boom of the nineteenth century came along with a demand from visitors for images that captured the places they had seen. During the 19th century, more than 400 artists painted White Mountain landscape scenes. Among them was Edward Hill (1843– 1923), who immigrated to New Hampshire from England as a child, bought land in Lancaster, NH, in the 1870s and established a reputation as a landscape painter. For 15 years he was the artist-in-residence at the famed Profile House, and it was during that time that he painted the Old Man of the Mountain. -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

The Artist and the American Land

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1975 A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land Norman A. Geske Director at Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska- Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Geske, Norman A., "A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land" (1975). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 112. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/112 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME I is the book on which this exhibition is based: A Sense at Place The Artist and The American Land By Alan Gussow Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 79-154250 COVER: GUSSOW (DETAIL) "LOOSESTRIFE AND WINEBERRIES", 1965 Courtesy Washburn Galleries, Inc. New York a s~ns~ 0 ac~ THE ARTIST AND THE AMERICAN LAND VOLUME II [1 Lenders - Joslyn Art Museum ALLEN MEMORIAL ART MUSEUM, OBERLIN COLLEGE, Oberlin, Ohio MUNSON-WILLIAMS-PROCTOR INSTITUTE, Utica, New York AMERICAN REPUBLIC INSURANCE COMPANY, Des Moines, Iowa MUSEUM OF ART, THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, University Park AMON CARTER MUSEUM, Fort Worth MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON MR. TOM BARTEK, Omaha NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington, D.C. MR. THOMAS HART BENTON, Kansas City, Missouri NEBRASKA ART ASSOCIATION, Lincoln MR. AND MRS. EDMUND c. -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

America Past

A Teacher’s Guide to America Past Sixteen 15-minute programs on the social history of the United States for high school students Guide writer: Jim Fleet Series consultant: John Patrick 01987 KRMA-W, Denver, Colorado and Agency for Instructional Technology Bloomington, Indiana AH rights reserved. This guide, or any part of it, may not be reproduced without written permission. Review questions in this guide maybe reproduced and distributed free to students. All inquiries should be addressed to: Agency for Instructional Technology Box A Bloomington, Indiana 47402 Table Of Contents Introduction To The AmericaPastSeries . 4 About Jim Fleet . ...!.... 5 America Past: An Overview . 5 How To Use This Guide . 5 Sources On People And Places In America Past . 5 Programs I. New Spain . 6 2. New France . 9 3. The Southern Colonies . 11 4. New England Colonies . 13 5. Canals and Steamboats . 16 6. Roads and Railroads, . .19 7. The Artist’s View . ... ..,.. 22 8. The Writer’s View . ...25 9. The Abolitionists . ...27 10. The Role of Women . ...29 ll. Utopias . ...31 12. Religion . ...33 13. Social Life . ...35 14. Moving West . ...38 15. The Industrial North . ...41 16. The Antebellum South . ...43 Textbook Correlation Chart . ...46 AnswerKey . ...48 Introduction To The America Past Series Over the past thirty years, it has been my experience that most textbooks and visual aids do an adequate job of cover- ing the political and economic aspects of American history UntiI recently however, scant attention has been given to social history. America Past was created to fill that gap. Some programs, such as those on religion and utopias, elaborate upon topics that may receive only a paragraph or two in many texts. -

Shoes & Brews Kicks Off Handing Over History. Old Man Site to Be Turned Over to the State in 2020. Pages 2

A1 GET OUT Shoes & Brews Kicks Off FRIDAY, JAN. 3, 2020 Page 13 Cyan Magenta Yellow Yellow Black Handing Over History. Old Man Site To Be Turned Over To The State In 2020. Pages 2 A2 2 The Record Friday, January 3, 2020 Cyan FILE PHOTO Magenta A steel “profiler” recreates the image of the Old Man as seen from Profile Plaza on Friday, Aug. 28, 2015. Yellow Yellow Old Man Memorial Site To Be Turned Over To State In 2020 Black them engraved with their names and messages. BY ROBERT BLECHL Remaining are just two more projects - the first, Staff Writer a walkway to Profile Lake, to the deepest part, that will accommodate those with disabilities and For a decade in Franconia Notch State Park, the include small fishing platform, and the second, a Old Man of the Mountain Legacy Fund has been larger platform over the wetlands that will connect making a lasting memorial to the Old Man of the to the Pemigewasset Trail. Mountain, the state’s most famous rock formation “When the turnover to the state happens will resembling a human profile that crumbled in May depend on when we complete these two projects,” 2003. said Hamilton. In 2020, once the last phase is completed, the The walkway of crushed stone to the lake will legacy fund will turn the memorial site over to the lead to the small platform. state. “It’s for fishermen to cast their flies and for peo- “We’re excited,” Dick Hamilton, a founding ple to enjoy the view from there, because it’s really member and past president of the OMMLF, said spectacular,” said Hamilton. -

Pemigewasset River Draft Study Report, New Hampshire

I PEMIGEWASSET Wil.D AND SCENIC RIVER STUDY DRAFT REPORT MARCH 1996 PEMIGl:WASSl:T WilD AND SCENIC RIVER STUDY M.iU!C:H 1996 Prepared by: New England System Support Office National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 15 State Street Boston, MA 02109 @ Printed on recycled paper I TABLE OF CONTENTS I o e 1.A The National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act/13 Proposed Segment Classification l .B Study Background/13 land Cover 1. C Study Process/ 14 Zoning Districts 1 .D Study Products/16 Public lands Sensitive Areas e 0 2.A Eligibilily and Classification Criteria/21 2.B Study Area Description/22 A. Study Participants 2.C Free-flowing Character/23 B. Pemigewasset River Management Plan 2.D Outstanding Resource Values: C. Draft Eligibilily and Classification Report Franconia Notch Segment/23 D. Town River Conservation Regulations 2.E Outstanding Resource Values: Valley Segment/24 E. Surveys 2.F Proposed Classifications/25 F. Official Correspondenc~ e 3.A Principal Factors of Suitabilily/31 3.B Evaluation of Existing Protection: Franconia Notch Segment/31 3.C Evaluation of Existing Protection: Valley Segment/32 3.D Public Support for River Conservation/39 3.E Public Support for Wild and Scenic Designation/39 3.F Summary of Findings/ 44 0 4.A Alternatives/ 47 4.B Recommended Action/ 48 The Pemigewasset Wild and Scenic River Study Draft Report was edited by Jamie Fosburgh and designed by Victoria Bass, National Park Service. ~----------------------------- - ---- -- ! ' l l I I I l I IPEMIGEWASSET RIVER STUDYI federal laws and regulations, public and private land own ership for conservation purposes, and physical constraints to additional shoreland development. -

As Time Passes Over the Land

s Time Passes over theLand A White Mountain Art As Time Passes over the Land is published on the occasion of the exhibition As Time Passes over the Land presented at the Karl Drerup Art Gallery, Plymouth State University, Plymouth, NH February 8–April 11, 2011 This exhibition showcases the multifaceted nature of exhibitions and collections featured in the new Museum of the White Mountains, opening at Plymouth State University in 2012 The Museum of the White Mountains will preserve and promote the unique history, culture, and environmental legacy of the region, as well as provide unique collections-based, archival, and digital learning resources serving researchers, students, and the public. Project Director: Catherine S. Amidon Curator: Marcia Schmidt Blaine Text by Marcia Schmidt Blaine and Mark Green Edited by Jennifer Philion and Rebecca Chappell Designed by Sandra Coe Photography by John Hession Printed and bound by Penmor Lithographers Front cover The Crawford Valley from Mount Willard, 1877 Frank Henry Shapleigh Oil on canvas, 21 x 36 inches From the collection of P. Andrews and Linda H. McLane © 2011 Mount Washington from Intervale, North Conway, First Snow, 1851 Willhelm Heine Oil on canvas, 6 x 12 inches Private collection Haying in the Pemigewasset Valley, undated Samuel W. Griggs Oil on canvas, 18 x 30 inches Private collection Plymouth State University is proud to present As Time Passes over the about rural villages and urban perceptions, about stories and historical Land, an exhibit that celebrates New Hampshire’s splendid heritage of events that shaped the region, about environmental change—As Time White Mountain School of painting. -

The Old Man of the Mountain

The Old Man Of The Mountain High above the Franconia Notch gateway to northern New Hampshire there is an old man. He has been described as a relentless tyrant, a fantastic freak, and a learned philosopher, feeble and weak about the mouth and of rarest beauty, stern and solemn, one of the most remarkable wonders of the mountain world. Daniel Webster once said, ..."Men hang out their signs indicative of their respective trades; shoe makers hang out a gigantic shoe; jewelers a monster watch, and the dentist hangs out a gold tooth; but up in the Mountains of New Hampshire, God Almighty has hung out a sign to show that there He makes men." Thus it happens that New Hampshire has her Profile, "The Old Man of the Mountain," sublimely outlined against the western sky; a sign unique, distinctive, and inspirational as to the kind of men the sons of the Granite State should be. ** The Old Man of the Mountain has several names including "The Profile", "The Great Stone Face", "The Old Man," and "The Old Man of the Mountains". The Profile is composed of Conway red granite and is an illusion formed by five ledges, that when lined up correctly give the appearance of an old man with an easterly gaze, clearly distinct and visible from only a very small space near Profile Lake. When viewed from other locations in Franconia Notch, the same five ledges have a very rough and ragged appearance, and there is no suggestion of The Profile.* Geological opinion is that The Profile on Profile Mountain is supposed to have been brought forth partly as the result of the melting and slipping away action of the ice sheet that covered the Franconia Mountains at the end of the glacial period, and partly by the action of the frost and ice in crevices, forcing off, and moving about certain rocks and ledges into profile forming positions.