As Time Passes Over the Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NH Trout Stocking - April 2018

NH Trout Stocking - April 2018 Town WaterBody 3/26‐3/30 4/02‐4/06 4/9‐4/13 4/16‐4/20 4/23‐4/27 4/30‐5/04 ACWORTH COLD RIVER 111 ALBANY IONA LAKE 1 ALLENSTOWN ARCHERY POND 1 ALLENSTOWN BEAR BROOK 1 ALLENSTOWN CATAMOUNT POND 1 ALSTEAD COLD RIVER 1 ALSTEAD NEWELL POND 1 ALSTEAD WARREN LAKE 1 ALTON BEAVER BROOK 1 ALTON COFFIN BROOK 1 ALTON HURD BROOK 1 ALTON WATSON BROOK 1 ALTON WEST ALTON BROOK 1 AMHERST SOUHEGAN RIVER 11 ANDOVER BLACKWATER RIVER 11 ANDOVER HIGHLAND LAKE 11 ANDOVER HOPKINS POND 11 ANTRIM WILLARD POND 1 AUBURN MASSABESIC LAKE 1 1 1 1 BARNSTEAD SUNCOOK LAKE 1 BARRINGTON ISINGLASS RIVER 1 BARRINGTON STONEHOUSE POND 1 BARTLETT THORNE POND 1 BELMONT POUT POND 1 BELMONT TIOGA RIVER 1 BELMONT WHITCHER BROOK 1 BENNINGTON WHITTEMORE LAKE 11 BENTON OLIVERIAN POND 1 BERLIN ANDROSCOGGIN RIVER 11 BRENTWOOD EXETER RIVER 1 1 BRISTOL DANFORTH BROOK 11 BRISTOL NEWFOUND LAKE 1 BRISTOL NEWFOUND RIVER 11 BRISTOL PEMIGEWASSET RIVER 11 BRISTOL SMITH RIVER 11 BROOKFIELD CHURCHILL BROOK 1 BROOKFIELD PIKE BROOK 1 BROOKLINE NISSITISSIT RIVER 11 CAMBRIDGE ANDROSCOGGIN RIVER 1 CAMPTON BOG POND 1 CAMPTON PERCH POND 11 CANAAN CANAAN STREET LAKE 11 CANAAN INDIAN RIVER 11 NH Trout Stocking - April 2018 Town WaterBody 3/26‐3/30 4/02‐4/06 4/9‐4/13 4/16‐4/20 4/23‐4/27 4/30‐5/04 CANAAN MASCOMA RIVER, UPPER 11 CANDIA TOWER HILL POND 1 CANTERBURY SPEEDWAY POND 1 CARROLL AMMONOOSUC RIVER 1 CARROLL SACO LAKE 1 CENTER HARBOR WINONA LAKE 1 CHATHAM BASIN POND 1 CHATHAM LOWER KIMBALL POND 1 CHESTER EXETER RIVER 1 CHESTERFIELD SPOFFORD LAKE 1 CHICHESTER SANBORN BROOK -

The Following Document Comes to You From

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) ACTS AND RESOLVES AS PASSED BY THE Ninetieth and Ninety-first Legislatures OF THE STATE OF MAINE From April 26, 1941 to April 9, 1943 AND MISCELLANEOUS STATE PAPERS Published by the Revisor of Statutes in accordance with the Resolves of the Legislature approved June 28, 1820, March 18, 1840, March 16, 1842, and Acts approved August 6, 1930 and April 2, 193I. KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA, MAINE 1943 PUBLIC LAWS OF THE STATE OF MAINE As Passed by the Ninety-first Legislature 1943 290 TO SIMPLIFY THE INLAND FISHING LAWS CHAP. 256 -Hte ~ ~ -Hte eOt:l:llty ffi' ft*; 4tet s.e]3t:l:ty tfl.a.t mry' ~ !;;llOWR ~ ~ ~ ~ "" hunting: ffi' ftshiRg: Hit;, ffi' "" Hit; ~ mry' ~ ~ ~, ~ ft*; eounty ~ ft8.t rett:l:rRes. ~ "" rC8:S0R8:B~e tffi:re ~ ft*; s.e]38:FtaFe, ~ ~ ffi" 5i:i'ffi 4tet s.e]3uty, ~ 5i:i'ffi ~ a-5 ~ 4eeme ReCCSS8:F)-, ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ffi'i'El, 4aH ~ eRtitles. 4E; Fe8:50nable fee5 ffi'i'El, C!E]3C::lSCS ~ ft*; sen-ices ffi'i'El, ~ ft*; ffi4s, ~ ~ ~ ~ -Hte tFeasurcr ~ ~ eouRty. BefoFc tfte sffi4 ~ €of' ~ ~ 4ep i:tt;- ~ ffle.t:J:.p 8:s.aitional e1E]3cfisc itt -Hte eM, ~ -Hte ~ ~~' ~, ftc ~ ~ -Hte conseRt ~"" lIiajority ~ -Hte COt:l:fity COfi111'lissioReFs ~ -Hte 5a+4 coufity. Whenever it shall come to the attention of the commis sioner -

1922 Elizabeth T

co.rYRIG HT, 192' The Moootainetro !scot1oror,d The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME FIFTEEN Number One D EC E M BER 15, 1 9 2 2 ffiount Adams, ffiount St. Helens and the (!oat Rocks I ncoq)Ora,tecl 1913 Organized 190!i EDITORlAL ST AitF 1922 Elizabeth T. Kirk,vood, Eclttor Margaret W. Hazard, Associate Editor· Fairman B. L�e, Publication Manager Arthur L. Loveless Effie L. Chapman Subsc1·iption Price. $2.00 per year. Annual ·(onl�') Se,·ent�·-Five Cents. Published by The Mountaineers lncorJ,orated Seattle, Washington Enlerecl as second-class matter December 15, 19t0. at the Post Office . at . eattle, "\Yash., under the .-\0t of March 3. 1879. .... I MOUNT ADAMS lllobcl Furrs AND REFLEC'rION POOL .. <§rtttings from Aristibes (. Jhoutribes Author of "ll3ith the <6obs on lltount ®l!!mµus" �. • � J� �·,,. ., .. e,..:,L....._d.L.. F_,,,.... cL.. ��-_, _..__ f.. pt",- 1-� r�._ '-';a_ ..ll.-�· t'� 1- tt.. �ti.. ..._.._....L- -.L.--e-- a';. ��c..L. 41- �. C4v(, � � �·,,-- �JL.,�f w/U. J/,--«---fi:( -A- -tr·�� �, : 'JJ! -, Y .,..._, e� .,...,____,� � � t-..__., ,..._ -u..,·,- .,..,_, ;-:.. � --r J /-e,-i L,J i-.,( '"'; 1..........,.- e..r- ,';z__ /-t.-.--,r� ;.,-.,.....__ � � ..-...,.,-<. ,.,.f--· :tL. ��- ''F.....- ,',L � .,.__ � 'f- f-� --"- ��7 � �. � �;')'... f ><- -a.c__ c/ � r v-f'.fl,'7'71.. I /!,,-e..-,K-// ,l...,"4/YL... t:l,._ c.J.� J..,_-...A 'f ',y-r/� �- lL.. ��•-/IC,/ ,V l j I '/ ;· , CONTENTS i Page Greetings .......................................................................tlristicles }!}, Phoiitricles ........ r The Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and the Goat Rocks Outing .......................................... B1/.ith Page Bennett 9 1 Selected References from Preceding Mount Adams and Mount St. -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

Maine Boating 2008 Laws & Rules

Maine State Library Maine State Documents Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books Inland Fisheries and Wildlife 1-1-2008 Maine Boating 2008 Laws & Rules Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books Recommended Citation "Maine Boating 2008 Laws & Rules" (2008). Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books. 479. http://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books/479 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife at Maine State Documents. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books by an authorized administrator of Maine State Documents. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATE OF MAINE BOATING 2008 LAW S & RU L E S www.maine.gov/ifw STATE OF MAINE BOATING 2008 LAW S & RU L E S www.maine.gov/ifw MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR & COMMISSIONER With an impressive inventory of 6,000 lakes and ponds, 3,000 miles of coastline, and over 32,000 miles of rivers and streams, Maine is truly a remarkable place for you to launch your boat and enjoy the variety and beauty of our waters. Providing public access to these bodies of water is extremely impor- tant to us because we want both residents and visitors alike to enjoy them to the fullest. The Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife works diligently to provide access to Maine’s waters, whether it’s a remote mountain pond, or Maine’s Casco Bay. How you conduct yourself on Maine’s waters will go a long way in de- termining whether new access points can be obtained since only a fraction of our waters have dedicated public access. -

Partnership Opportunities for Lake-Friendly Living Service Providers NH LAKES Lakesmart Program

Partnership Opportunities for Lake-Friendly Living Service Providers NH LAKES LakeSmart Program Only with YOUR help will New Hampshire’s lakes remain clean and healthy, now and in the future. The health of our lakes, and our enjoyment of these irreplaceable natural resources, is at risk. Polluted runoff water from the landscape is washing into our lakes, causing toxic algal blooms that make swimming in lakes unsafe. Failing septic systems and animal waste washed off the land are contributing bacteria to our lakes that can make people and pets who swim in the water sick. Toxic products used in the home, on lawns, and on roadways and driveways are also reaching our lakes, poisoning the water in some areas to the point where fish and other aquatic life cannot survive. NH LAKES has found that most property owners don’t know how their actions affect the health of lakes. We’ve also found that property owners want to do the right thing to help keep the lakes they enjoy clean and healthy and that they often need help of professional service providers like YOU! What is LakeSmart? The LakeSmart program is an education, evaluation, and recognition program that inspires property owners to live in a lake- friendly way, keeping our lakes clean and healthy. The program is free, voluntary, and non-regulatory. Through a confidential evaluation process, property owners receive tailored recommendations about how to implement lake-friendly living practices year-round in their home, on their property, and along and on the lake. Property owners have access to a directory of lake- friendly living service providers to help them adopt lake-friendly living practices. -

NHHS Consuming Views

CONTRIBUTORS Heidi Applegate wrote an introductory essay for Hudson River Janice T. Driesbach is the director of the Sheldon Memorial Art School Visions: The Landscapes of Sanford R. Gifford (Metro- Gallery and Sculpture Garden at the University of Nebraska- politan Museum of Art, 2003). Formerly of the National Lincoln. She is the author of Direct from Nature: The Oil Gallery of Art, she is now a doctoral candidate in art history at Sketches of Thomas Hill (Yosemite Association in association Columbia University. with the Crocker Art Museum, 1997). Wesley G. Balla is director of collections and exhibitions at the Donna-Belle Garvin is the editor of Historical New Hampshire New Hampshire Historical Society. He was previously curator and former curator of the New Hampshire Historical Society. of history at the Albany Institute of History and Art. He has She is coauthor of the Society’s On the Road North of Boston published on both New York and New Hampshire topics in so- (1988), as well as of the catalog entries for its 1982 Shapleigh cial and cultural history. and 1996 Champney exhibitions. Georgia Brady Barnhill, the Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Elton W. Hall produced an exhibition and catalog on New Bed- Graphic Arts at the American Antiquarian Society, is an au- ford, Massachusetts, artist R. Swain Gifford while curator of thority on printed views of the White Mountains. Her “Depic- the Old Dartmouth Historical Society. Now executive director tions of the White Mountains in the Popular Press” appeared in of the Early American Industries Association, he has published Historical New Hampshire in 1999. -

Great Vacation Times at Chocorua Camping Village & Wabanaki Lodge & the Greater Ossipee - Chocorua Mountain Region for Toll-Free Reservations 1-888-237-8642 Vol

Great Vacation Times at Chocorua Camping Village & Wabanaki Lodge & the Greater Ossipee - Chocorua Mountain Region For Toll-Free reservaTions 1-888-237-8642 Vol. 19 No. 1 GPS: 893 White Mountain Hwy, Tamworth, NH 03886 PO Box 484, Chocorua, NH 03817 email: [email protected] Tel. 1-888-BEST NHCampground (1-888-237-8642) or 603-323-8536 www.ChocoruaCamping.com www.WhiteMountainsLodging.com We Trust That You’ll Our Awesome Park! Escape the noisy rush of the city. Pack up and leave home on a get-away adventure! Come join the vacation tradition of our spacious, forested Chocorua Camping Village KOA! Miles of nature trails, a lake-size pond and river to explore by kayak. We offer activities all week with Theme Weekends to keep the kids and family entertained. Come by tent, pop-up, RV, or glamp-it-up in new Tipis, off-the-grid cabins or enjoy easing into full-amenity lodges. #BringTheDog #Adulting Young Couples... RVers Rave about their Families who Camp Together - Experience at CCV Stay Together, even when apart ...often attest to the rustic, lakeside cabins of You have undoubtedly worked long and hard to earn Why is it that both parents and children look forward Wabanaki Lodge as being the Sangri-La of the White ownership of the RV you now enjoy. We at Chocorua with such excitement and enthusiasm to their frequent Mountains where they can enjoy a simple cabin along Camping Village-KOA appreciate and respect that fact; weekends and camping vacations at Chocorua Camping the shore of Moores Pond, nestled in the privacy of a we would love to reward your achievement with the Village—KOA? woodland pine grove. -

Tatewell Gallery

WWW.GRANITEQUILL.COM | OCTOBER 2012 | SENIOR LIFESTYLES | PAGE 17 Tips for seniors on managing health care costs Finding the Medicare coverage that year by switching drug plans. "I thought best fits their needs and their pocket- a mail-order prescription plan was best books is challenging for many seniors. for me, but their specialists proved me Health care plans make changes to their wrong about this, and I am so happy," coverage. People's health conditions she says. change. Not keeping on top of these 3. Be proactive. Having known changes can mean problems. Suddenly and been around seniors, Hercules says seniors may find they don't have needed she is saddened that so many settle for coverage, their doctor no longer takes high costs or keep the same Medicare their plan, or they face steep medical or plan year after year because of a lack of prescription drug costs. niors can capitalize on those savings by understanding. That's why it's essential to review knowing exactly what they are paying Just as seniors review their finances Medicare coverage and individual needs for and shop around for better prescrip- or taxes each year, Medicare annual each year, and to use the Medicare an- tion prices and ask about costs. For addi- enrollment is the ideal time to review nual open enrollment period to make tional savings, use generic medications. health care coverage, Walters says. "It's changes to coverage. 2. Ask for help. In addition to guid- OK to admit it's confusing and that help 1. Be an informed consumer. -

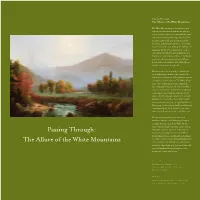

Passing Through: the Allure of the White Mountains

Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains The White Mountains presented nineteenth- century travelers with an American landscape: tamed and welcoming areas surrounded by raw and often terrifying wilderness. Drawn by the natural beauty of the area as well as geologic, botanical, and cultural curiosities, the wealthy began touring the area, seeking the sublime and inspiring. By the 1830s, many small-town tav- erns and rural farmers began lodging the new travelers as a way to make ends meet. Gradually, profit-minded entrepreneurs opened larger hotels with better facilities. The White Moun- tains became a mecca for the elite. The less well-to-do were able to join the elite after midcentury, thanks to the arrival of the railroad and an increase in the number of more affordable accommodations. The White Moun- tains, close to large East Coast populations, were alluringly beautiful. After the Civil War, a cascade of tourists from the lower-middle class to the upper class began choosing the moun- tains as their destination. A new style of travel developed as the middle-class tourists sought amusement and recreation in a packaged form. This group of travelers was used to working and commuting by the clock. Travel became more time-oriented, space-specific, and democratic. The speed of train travel, the increased numbers of guests, and a widening variety of accommodations opened the White Moun- tains to larger groups of people. As the nation turned its collective eyes west or focused on Passing Through: the benefits of industrialization, the White Mountains provided a nearby and increasingly accessible escape from the multiplying pressures The Allure of the White Mountains of modern life, but with urban comforts and amenities. -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County