Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D4 DEACCESSION LIST 2019-2020 FINAL for HLC Merged.Xlsx

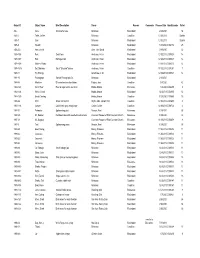

Object ID Object Name Brief Description Donor Reason Comments Process Date Box Barcode Pallet 496 Vase Ornamental vase Unknown Redundant 2/20/2020 54 1975-7 Table, Coffee Unknown Condition 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-7 Saw Unknown Redundant 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-9 Wrench Unknown Redundant 1/28/2020 C002172 25 1978-5-3 Fan, Electric Baer, John David Redundant 2/19/2020 52 1978-10-5 Fork Small form Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-7 Fork Barbeque fork Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-9 Masher, Potato Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-16 Set, Dishware Set of "Bluebird" dishes Anderson, Helen Condition 11/12/2019 C001351 7 1978-11 Pin, Rolling Grantham, C. W. Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1981-10 Phonograph Sonora Phonograph Co. Unknown Redundant 2/11/2020 1984-4-6 Medicine Dr's wooden box of antidotes Fugina, Jean Condition 2/4/2020 42 1984-12-3 Sack, Flour Flour & sugar sacks, not local Hobbs, Marian Relevance 1/2/2020 C002250 9 1984-12-8 Writer, Check Hobbs, Marian Redundant 12/3/2019 C002995 12 1984-12-9 Book, Coloring Hobbs, Marian Condition 1/23/2020 C001050 15 1985-6-2 Shirt Arrow men's shirt Wythe, Mrs. Joseph Hills Condition 12/18/2019 C003605 4 1985-11-6 Jumper Calvin Klein gray wool jumper Castro, Carrie Condition 12/18/2019 C001724 4 1987-3-2 Perimeter Opthamology tool Benson, Neal Relevance 1/29/2020 36 1987-4-5 Kit, Medical Cardboard box with assorted medical tools Covenant Women of First Covenant Church Relevance 1/29/2020 32 1987-4-8 Kit, Surgical Covenant -

Bibliography

Professor Peter Henriques, Emeritus E-Mail: [email protected] Recommended Books on George Washington 1. Paul Longmore, The Invention of GW 2. Noemie Emery, Washington: A Biography 3. James Flexner, GW: Indispensable Man 4. Richard Norton Smith, Patriarch 5. Richard Brookhiser, Founding Father 6. Marcus Cunliffe, GW: Man and Monument 7. Robert Jones, George Washington [2002 edition] 8. Don Higginbotham, GW: Uniting a Nation 9. Jack Warren, The Presidency of George Washington 10. Peter Henriques, George Washington [a brief biography for the National Park Service. $10.00 per copy including shipping.] Note: Most books can be purchased at amazon.com. A Few Important George Washington Web sites http://chnm.gmu.edu/courses/henriques/hist615/index.htm [This is my primitive website on GW and has links to most of the websites listed below plus other material on George Washington.] www.virginia.edu/gwpapers [Website for GW papers at UVA. Excellent.] http://etext.virginia.edu/washington [The Fitzpatrick edition of the GW Papers, all word searchable. A wonderful aid for getting letters on line.] http://georgewashington.si.edu [A great interactive site for students of all grades focusing on Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne portrait of GW.] http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/presiden/washpap.htm [The Avalon Project which contains GW’s inaugural addresses and many speeches.] http://www.mountvernon.org [The website for Mount Vernon.] Additional Books and Websites, 2004 Joe Ellis, His Excellency, October 2004 [This will be a very important book by a Pulitzer winning -

National US History Bee Round #1

National US History Bee Round 1 1. This group had a member who used the alias “Robert Rich” when writing The Brave One and who had previously written the anti-war novel Johnny Get Your Gun. This group was vindicated when member Dalton Trumbo received a credit for the movie Spartacus. Who were these screenwriters cited for contempt of Congress and blacklisted after refusing to testify before the anti-Communist HUAC? ANSWER: Hollywood Ten 052-13-92-01101 2. This man is seen pointing to a curiously bewigged child in a Grant Wood painting about his “fable.” This man invented a popular story in which a father praises the “act of heroism” of his son when the latter insists “I cannot tell a lie” after cutting down a cherry tree. Who is this man who invented numerous stories about George Washington for an 1800 biography? ANSWER: Parson Weems [or Mason Locke Weems] 052-13-92-01102 3. This building is depicted in Charles Wilson Peale’s self-portrait The Artist in His Museum. This building is where James Wilson proposed a compromise in a meeting convened after the Annapolis Convention suggested revising the Articles of Confederation. What is this Philadelphia building, the site of the Constitutional Convention? ANSWER: Independence Hall [or Old State House of Pennsylvania] 052-13-92-01103 4. This event's completion resulted in Major Ridge and Elias Boudinot's assassination by dissidents. This event was put into action after the Treaty of New Echota was signed. This event began at Red Clay, Tennessee, and many participants froze to death at places like Mantle Rock. -

Rembrandt Peale, Charles Willson Peale, and the American Portrait Tradition

In the Shadow of His Father: Rembrandt Peale, Charles Willson Peale, and the American Portrait Tradition URING His LIFETIME, Rembrandt Peale lived in the shadow of his father, Charles Willson Peale (Fig. 8). In the years that Dfollowed Rembrandt's death, his career and reputation contin- ued to be eclipsed by his father's more colorful and more productive life as successful artist, museum keeper, inventor, and naturalist. Just as Rembrandt's life pales in comparison to his father's, so does his art. When we contemplate the large number and variety of works in the elder Peak's oeuvre—the heroic portraits in the grand manner, sensitive half-lengths and dignified busts, charming conversation pieces, miniatures, history paintings, still lifes, landscapes, and even genre—we are awed by the man's inventiveness, originality, energy, and daring. Rembrandt's work does not affect us in the same way. We feel great respect for his technique, pleasure in some truly beau- tiful paintings, such as Rubens Peale with a Geranium (1801: National Gallery of Art), and intellectual interest in some penetrating char- acterizations, such as his William Findley (Fig. 16). We are impressed by Rembrandt's sensitive use of color and atmosphere and by his talent for clear and direct portraiture. However, except for that brief moment following his return from Paris in 1810 when he aspired to history painting, Rembrandt's work has a limited range: simple half- length or bust-size portraits devoid, for the most part, of accessories or complicated allusions. It is the narrow and somewhat repetitive nature of his canvases in comparison with the extent and variety of his father's work that has given Rembrandt the reputation of being an uninteresting artist, whose work comes to life only in the portraits of intimate friends or members of his family. -

Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn

'Memorials of great & good men who were my friends'': Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn ELLEN G. MILES LIVER woLCOTT, JR. (1760-1833), like many of his contemporaries, used portraits as familial icons, as ges- Otures in political alliances, and as public tributes and memorials. Wolcott and his father Oliver Wolcott, Sr. (i 726-97), were prominent in Connecticut politics during the last quarter of the eighteenth century and the first quarter of the nineteenth. Both men served as governors of the state. Wolcott, Jr., also served in the federal administrations of George Washington and John Adams. Withdrawing from national politics in 1800, he moved to New York City and was a successful merchant and banker until 1815. He spent the last twelve years of his public life in Con- I am grateful for a grant from the Smithsonian Institution's Research Opportunities Fund, which made it possible to consult manuscripts and see portraits in collecdüns in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, New Haven, î lartford. and Litchfield (Connecticut). Far assistance on these trips I would like to thank Robin Frank of the Yale Universit)' Art Gallery, .'\nne K. Bentley of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Judith Ellen Johnson and Richard Malley of the Connecticut Historical Society, as well as the society's fonner curator Elizabeth Fox, and Elizabeth M. Komhauscr, chief curator at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford. David Spencer, a former Smithsonian Institution Libraries staff member, gen- erously assisted me with the VVolcott-Cibbs Family Papers in the Special Collectiims of the University of Oregon Library, Eugene; and tht staffs of the Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Ciallery, and the Inventory of American Painting. -

Reframing the Republic: Images and Art in Post-Revolutionary America" (2018)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University at Albany, State University of New York (SUNY): Scholars Archive University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive History Honors College 5-2018 Reframing the Republic: Images and Art in Post- Revolutionary America Lauren Lyons University at Albany, State University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/ honorscollege_history Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Lyons, Lauren, "Reframing the Republic: Images and Art in Post-Revolutionary America" (2018). History. 10. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_history/10 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reframing the Republic: Images and Art in Post-Revolutionary America An honors thesis presented to the Department of History University at Albany, State University of New York In partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in History and graduation from The Honors College. Lauren Lyons Research Mentor: Christopher Pastore, Ph.D. Second Reader: Ryan Irwin, Ph.D. May, 2018. Lyons 2 Abstract Following the American Revolution the United States had to prove they deserved to be a player on the European world stage. Images were one method the infant nation used to make this claim and gain recognition from European powers. By examining early American portraits, eighteenth and nineteenth century plays, and American and European propaganda this paper will argue that images were used to show the United States as a world power. -

Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery News Winter/Spring 2008 from the Acting Director

PROFILESmithsonian National Portrait Gallery News Winter/Spring 2008 From the Acting Director Over Presidents’ Day weekend, nearly 25,000 peo- Steichen: Portraits” pre- ple visited the Donald W. Reynolds Center. I would sents celebrity photo- like to think that what motivated so many to come graphs that complement Ken Rahaim to the museums at Gallery Place was the National those of the less-well-known Zaida Ben-Yusuf—the Portrait Gallery’s permanent collection, which is subject of the groundbreaking loan show “Zaida currently enhanced by the loan of Charles Willson Ben-Yusuf: New York Portrait Photographer.” If Peale’s splendid 1779 portrait of George Washing- you traveled to the National Portrait Gallery twice, ton after the Battle of Princeton. This iconic por- once in the winter and again in late spring, you trait of the triumphant General Washington com- would have seen “The Presidency and the Cold plements our own equally iconic “Lansdowne” War” and its replacement, “Herblock’s Presidents: portrait of Washington as president, completed by ‘Puncturing Pomposity,’” which takes a less-than- Gilbert Stuart in 1796. Both of these imposing por- reverential look at those who occupy our nation’s traits, which represent the cornerstones of Wash- highest office. Two one-person shows have also been ington’s career, were initially destined for European big draws: “KATE: A Centennial Celebration,” il- collections: Peale’s portrait was sent to Spain the luminates moments in the life of Katharine Hep- year it was completed, and Stuart’s portrait was a burn, while Stephen Colbert’s portrait, displayed gift to Lord Lansdowne, an English supporter of over the water fountains between the second-floor the American Revolution. -

Saving Washington Dolley Madison’S Extract

Resource 6: Saving Washington Dolley Madison’s Extract Tuesday Augt . 23d . 1814 . Dear Sister . —My husband left me yesterday morng . to join Gen . Wednesday morng ., twelve O’clock . Since sunrise I Winder . He enquired anxiously whether I had courage, have been turning my spy glass in every direction and or firmness to remain in the President’s house until his watching with unwearied anxiety, hoping to discern the return, on the morrow, or succeeding day, and on my approach of my dear husband and his friends; but, alas, assurance that I had no fear but for him and the success I can descry only groups of military wandering in all of our army, he left me, beseeching me to take care of directions, as if there was a lack of arms, or of spirit to myself, and of the cabinet papers, public and private . I fight for their own firesides! have since recd . two despatches from him, written with a pencil; the last is alarming, because he desires I should Three O’clock . Will you believe it, my Sister? We have be ready at a moment’s warning to enter my carriage and had a battle or skirmish near Bladensburg, and I am still leave the city; that the enemy seemed stronger than had here within sound of the cannon! Mr . Madison comes been reported and that it might happen that they would not; may God protect him! Two messengers covered reach the city, with intention to destroy it . X X X with dust, come to bid me fly; but I wait for him . -

George Washington (Lansdowne Portrait) by Gilbert Stuart

Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery (http://www.npg.si.edu/collection/lansdowne.html) George Washington (Lansdowne Portrait) by Gilbert Stuart Permanent installation: Second floor The "Lansdowne" portrait of George Washington is an American treasure, an iconic painting whose historical and cultural importance has been compared to that of the Liberty Bell and the Declaration of Independence. Painted by Gilbert Stuart, the most prestigious portraitist of his day, the 205-year-old painting has a storied past. The commonly used title—"Lansdowne"—is derived from the name of the person for whom it was painted, the first Marquis of Lansdowne. It was commissioned in 1796 by one of America's wealthiest men, Sen. William Bingham, and his wife Anne, for the marquis, a British supporter of the American cause in Parliament during the American Revolution. The gift was a remarkable gesture of gratitude and a symbol of reconciliation between America and Great Britain. The painting was displayed in Lansdowne's London mansion until his death in 1805, after which it remained in private hands and was eventually incorporated into the collection of the 5th Earl of Rosebery around 1890. The portrait was later hung in Dalmeny House, in West Lothian, Scotland. It has traveled to America only three times since its creation, the last time when it was loaned to the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery in 1968. Painted from life, the 8-foot-by-5-foot portrait shows Washington in a black velvet suit, with an oratorical gesture of the outstretched hand, the way he would appear at state occasions during his presidency. -

P-Winter 05.Indd

PSmithsonianR NationalOFIL Portrait Gallery ENews Winter 2005–6 From the DIRECTOR Charles Willson Peale, featured on our cover, is considered the father of Ameri- can museums, as well as one of the new Republic’s great portraitists. Because of this, and because the National Por- trait Gallery is home to the Peale Papers documentary history project, we have chosen the patriot artist’s great self-portrait to represent the unveiling of the renewed Gallery in July. But 2006 is not just a banner year for the National Portrait Gallery in Washington. It also marks the 150th anni- versary of the very idea of a national portrait gallery. In 1856 the first National Portrait Gallery opened in London, dedicated to telling the sto- ries of Britain’s greatest historical figures through the presentation of their portraits. The founding portrait was, fittingly, of William Shakespeare. More than a century later, our founding portrait—also fittingly—was Gil- bert Stuart’s “Lansdowne” portrait of George Washington (on long-term loan until we were able to purchase it some thirty years later). The English National Portrait Gallery set the standard for all future portrait galleries. Begun initially as their survey of noble lives alone, the English curators increasingly realized that they could not fully tell the story of those who had shaped their society without including a few notorious lives. The celebration of that magnificent collection will occur throughout 2006. We have hopes of bringing some of their greatest treasures, includ- ing Will Shakespeare himself, to Washington in the late spring of 2007 to acknowledge our debt to our mother institution. -

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

THE PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF THE FINE ARTS BROAD AND CHERRY STREETS • PHILADELPHIA 160th ANNUAL REPORT 196 5 Cover: Interior With Doorway by Richard Diebenkorn Gilpin Fund Purchase, 1964 The One Hundred and Sixtieth Annual Report of PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF THE FINE ARTS FOR THE YEAR 1965 Presented to the Meeting of the Stockholders of the Academy on February 7, 1966. OFFICERS Frank T. Howard · . President Alfred Zantzinger · Vice President C. Newbold Taylor . Treasurer Joseph T. Fraser, Jr. · . Secretary BOARD OF DIRECTORS Mrs. Leonard T. Beale John W. Merriam Francis Bosworth C. Earle Miller Mrs. Bertram D. Coleman Mrs. Herbert C. Morris (resigned, September) David Gwinn Evan Randolph, Jr. J. Welles Henderson Henry W. Sawyer, 3rd Frank T. Howard (ex officio) John Stewart R. Sturgis Ingersoll James K. Stone Arthur C. Kaufmann C. Newbold Taylor Henry B. Keep Franklin C. Watkins James M. Large William H. S. Wells James P. Magill (Director Emeritus) William Coxe Wright Henry S. McNeil Alfred Zantzinger Ex officio Representing Women's Committee: Mrs. H. Lea Hudson, Chairman (to May) Mrs. Erasmus Kloman, Vice Chairman (to May) Mrs. George Reath, Chairman (from May) Mrs. Erasmus Kloman, Vice Chairman (from May) Mrs. Albert M. Greenfield, Jr., Vice Chairman (from May) Representing City Council: Representing Faculty: Paul D'Ortona John W. McCoy 2nd (to May) Robert W. Crawford Hobson Pittman (from May) Solicitor: William H. S. Wells, Jr. 2 STANDING COMMITTEES COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITIONS Franklin C. Watkins, Chairman Mrs. Herbert C. Morris Mrs. Leonard T. Beale William H. S. Wells, Jr. James M. Large William Coxe Wright Alfred Zantzinger Representing Women's Committee: Mrs. -

"Visualizing Early American Art Audiences: the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Allston's Dead Man Restored"

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU English Faculty Publications English 2011 "Visualizing Early American Art Audiences: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Allston's Dead Man Restored" Yvette Piggush College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/english_pubs Recommended Citation Piggush, Yvette. "Visualizing Early American Art Audiences: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Allston's Dead Man Restored." Early American Studies 9.3 (2011): 716-47. Originally Published by University of Pennsylvania Press. "All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of scholarly citation, none of this work may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher. For information address the University of Pennsylvania Press, 3905 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112."art museums, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Washington Allston, audiences, reception, antique cast collections, spectatorship Visualizing Early American Art Audiences: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Allston's Dead Man Restored Yvette R. Piggush Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Volume 9, Number 3, Fall 2011, pp. 716-747 (Article) Published by University of Pennsylvania Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/eam.2011.0030 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/448113 Access provided by College of St. Benedict | St. John's University (28 Oct 2018 05:00 GMT) Visualizing Early American Art Audiences The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Allston’s Dead Man Restored YVETTE R.