Dissertation FINALLY.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shearer West Phd Thesis Vol 1

THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON (VOL. I) Shearer West A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 1986 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2982 This item is protected by original copyright THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON Ph.D. Thesis St. Andrews University Shearer West VOLUME 1 TEXT In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the I work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. ABSTRACT A theatrical portrait is an image of an actor or actors in character. This genre was widespread in eighteenth century London and was practised by a large number of painters and engravers of all levels of ability. The sources of the genre lay in a number of diverse styles of art, including the court portraits of Lely and Kneller and the fetes galantes of Watteau and Mercier. Three types of media for theatrical portraits were particularly prevalent in London, between ca745 and 1800 : painting, print and book illustration. -

![The Story of the Taovaya [Wichita]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0725/the-story-of-the-taovaya-wichita-20725.webp)

The Story of the Taovaya [Wichita]

THE STORY OF THE TAOVAYA [WICHITA] Home Page (Images Sources): • “Coahuiltecans;” painting from The University of Texas at Austin, College of Liberal Arts; www.texasbeyondhistory.net/st-plains/peoples/coahuiltecans.html • “Wichita Lodge, Thatched with Prairie Grass;” oil painting on canvas by George Catlin, 1834-1835; Smithsonian American Art Museum; 1985.66.492. • “Buffalo Hunt on the Southwestern Plains;” oil painting by John Mix Stanley, 1845; Smithsonian American Art Museum; 1985.66.248,932. • “Peeling Pumpkins;” Photogravure by Edward S. Curtis; 1927; The North American Indian (1907-1930); v. 19; The University Press, Cambridge, Mass; 1930; facing page 50. 1-7: Before the Taovaya (Image Sources): • “Coahuiltecans;” painting from The University of Texas at Austin, College of Liberal Arts; www.texasbeyondhistory.net/st-plains/peoples/coahuiltecans.html • “Central Texas Chronology;” Gault School of Archaeology website: www.gaultschool.org/history/peopling-americas-timeline. Retrieved January 16, 2018. • Terminology Charts from Lithics-Net website: www.lithicsnet.com/lithinfo.html. Retrieved January 17, 2018. • “Hunting the Woolly Mammoth;” Wikipedia.org: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hunting_Woolly_Mammoth.jpg. Retrieved January 16, 2018. • “Atlatl;” Encyclopedia Britannica; Native Languages of the Americase website: www.native-languages.org/weapons.htm. Retrieved January 19, 2018. • “A mano and metate in use;” Texas Beyond History website: https://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/kids/dinner/kitchen.html. Retrieved January 18, 2018. • “Rock Art in Seminole Canyon State Park & Historic Site;” Texas Parks & Wildlife website: https://tpwd.texas.gov/state-parks/seminole-canyon. Retrieved January 16, 2018. • “Buffalo Herd;” photograph in the Tales ‘N’ Trails Museum photo; Joe Benton Collection. A1-A6: History of the Taovaya (Image Sources): • “Wichita Village on Rush Creek;” Lithograph by James Ackerman; 1854. -

The Rhinehart Collection Rhinehart The

The The Rhinehart Collection Spine width: 0.297 inches Adjust as needed The Rhinehart Collection at appalachian state university at appalachian state university appalachian state at An Annotated Bibliography Volume II John higby Vol. II boone, north carolina John John h igby The Rhinehart Collection i Bill and Maureen Rhinehart in their library at home. ii The Rhinehart Collection at appalachian state university An Annotated Bibliography Volume II John Higby Carol Grotnes Belk Library Appalachian State University Boone, North Carolina 2011 iii International Standard Book Number: 0-000-00000-0 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 0-00000 Carol Grotnes Belk Library, Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina 28608 © 2011 by Appalachian State University. All rights reserved. First Edition published 2011 Designed and typeset by Ed Gaither, Office of Printing and Publications. The text face and ornaments are Adobe Caslon, a revival by designer Carol Twombly of typefaces created by English printer William Caslon in the 18th century. The decorative initials are Zallman Caps. The paper is Carnival Smooth from Smart Papers. It is of archival quality, acid-free and pH neutral. printed in the united states of america iv Foreword he books annotated in this catalogue might be regarded as forming an entity called Rhinehart II, a further gift of material embodying British T history, literature, and culture that the Rhineharts have chosen to add to the collection already sheltered in Belk Library. The books of present concern, diverse in their -

New York Painting Begins: Eighteenth-Century Portraits at the New-York Historical Society the New-York Historical Society Holds

New York Painting Begins: Eighteenth-Century Portraits at the New-York Historical Society The New-York Historical Society holds one of the nation’s premiere collections of eighteenth-century American portraits. During this formative century a small group of native-born painters and European émigrés created images that represent a broad swath of elite colonial New York society -- landowners and tradesmen, and later Revolutionaries and Loyalists -- while reflecting the area’s Dutch roots and its strong ties with England. In the past these paintings were valued for their insights into the lives of the sitters, and they include distinguished New Yorkers who played leading roles in its history. However, the focus here is placed on the paintings themselves and their own histories as domestic objects, often passed through generations of family members. They are encoded with social signals, conveyed through dress, pose, and background devices. Eighteenth-century viewers would have easily understood their meanings, but they are often unfamiliar to twenty-first century eyes. These works raise many questions, and given the sparse documentation from the period, not all of them can be definitively answered: why were these paintings made, and who were the artists who made them? How did they learn their craft? How were the paintings displayed? How has their appearance changed over time, and why? And how did they make their way to the Historical Society? The state of knowledge about these paintings has evolved over time, and continues to do so as new discoveries are made. This exhibition does not provide final answers, but presents what is currently known, and invites the viewer to share the sense of mystery and discovery that accompanies the study of these fascinating works. -

Seth Eastman, a Portfolio of North American Indians Desperately Needed for Repairs

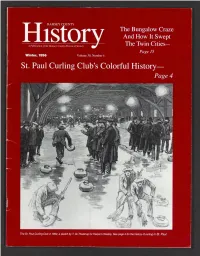

RAMSEY COUNTY The Bungalow Craze And How It Swept A Publication of the Ramsey County Historical Society The Twin Cities— Page 15 Winter, 1996 Volume 30, Number 4 St. Paul Curling Club’s Colorful History The St. Paul Curling Club in 1892, a sketch by T. de Thulstrup for Harper’s Weekly. See page 4 for the history of curling in S t Paul. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director Priscilla Famham Editor Virginia Brainard Kunz WARREN SCHABER 1 9 3 3 - 1 9 9 5 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY The Ramsey County Historical Society lost a BOARD OF DIRECTORS good friend when Ramsey County Commis Joanne A. Englund sioner Warren Schaber died last October Chairman of the Board at the age of sixty-two. John M. Lindley CONTENTS The Society came President to know him well Laurie Zehner 3 Letters during the twenty First Vice President years he served on Judge Margaret M. Mairinan the Board of Ramsey Second Vice President 4 Bonspiels, Skips, Rinks, Brooms, and Heavy Ice County Commission Richard A. Wilhoit St. Paul Curling Club and Its Century-old History Secretary ers. We were warmed by his steady support James Russell Jane McClure Treasurer of the Society and its work. Arthur Baumeister, Jr., Alexandra Bjorklund, 15 The Bungalows of the Twin Cities, With a Look Mary Bigelow McMillan, Andrew Boss, A thoughtful Warren We remember the Thomas Boyd, Mark Eisenschenk, Howard At the Craze that Created Them in St. Paul Schaber at his first County big things: the long Guthmann, John Harens, Marshall Hatfield, Board meeting, January 6, series of badly- Liz Johnson, George Mairs, III, Mary Bigelow Brian McMahon 1975. -

1833-1834 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design Art, Art History and Design, School of 2011 Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-1834 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida Kimberly Minor University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Art and Design Commons Minor, Kimberly, "Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-1834 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida" (2011). Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artstudents/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art, Art History and Design, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Student Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-34 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida By Kimberly Minor Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Art History Under the Supervision of Professor Wendy Katz Lincoln, Nebraska April 2011 Stealing Horses and Hostile Conflict: 1833-34 Drawings of Mato-Tope and Sih-Chida Kimberly Minor, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2011 Advisor: Wendy Katz The first documented Native American art on paper includes the following drawings at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska: In the Winter, 1833-1834 (two versions) by Sih-Chida (Yellow Feather) and Mato-Tope Battling a Cheyenne Chief with a Hatchet (1834) by Mato-Tope (Four Bears) as well as an untitled drawing not previously attributed to the latter. -

Examine the Exquisite Portraits of the American Indian Leaders Mckenney

Examine the exquisite portraits of the American Indian leaders McKenney, Thomas, and James Hall, History of the Indian Tribes of North America. Philadelphia: Edward C. Biddle (parts 1-5), Frederick W. Greenough (parts 6-13), J.T. Bowen (part 14), Daniel Rice and James G. Clark (parts 15-20), [1833-] 1837-1844 20 Original parts, folio (21.125 x 15.25in.: 537 x 389 mm.). 117 handcolored lithographed portraits after C. B. King, 3 handcolored lithographed scenic frontispieces after Rindisbacher, leaf of lithographed maps and table, 17 pages of facsimile signatures of subscribers, leaf of statements of the genuiness of the portrait of Pocahontas, part eight with the printed notice of the correction of the description of the War Dance and the cancel leaf of that description (the incorrect cancel and leaf in part 1), part 10 with erratum slip, part 20 with printed notice to binders and subscribers, title pages in part 1 (volume 1, Biddle imprint 1837), 9 (Greenough imprint, 1838), 16 (volume 2, Rice and Clark imprint, 1842), and 20 (volume 3, Rice and Clark imprint, 1844); some variously severe but, usually light offsetting and foxing, final three parts with marginal wormholes, not affecting text or images. Original printed buff wrappers; part 2 with spine lost and rear wrapper detached, a few others with spines shipped, part 11 with sewing broken and text and plates loose, part 17 with large internal loss of front wrapper affecting part number, some others with marginal tears or fraying, some foxed or soiled. Half maroon morocco folding-case, gilt rubbed. FIRST EDITION, second issue of title-page of volume 1. -

James Otto Lewis' the Aboriginal Portfolio

James Otto Lewis' The Aboriginal Portfolio Bibliography 1. The Aboriginal Portfolio. See Also The North American Aboriginal Portfolio. 2. "Albert Newsam Folder." Library Company of Philadelphia. Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Notes: Source: Viola. The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King. 1976. Source: Viola. Thomas L. McKenney: Architect of America's Early Indian Policy: 1816‐1830. 1974. 3. Alexandria Gazette [Microform] (Alexandria, Virginia), 1800‐. Notes: Source: Viola. The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King. 1976. Source: WorldCat. 4. American Saturday Courier (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), 1900a. Notes: American Saturday Courier. Philadelphia, ca. 1830‐1856. WorldCat: 10284376. The Philadelphia Saturday Bulletin. Philadelphia, ca. 1856‐1860. WorldCat: 12632171. The Philadelphia Saturday Bulletin and American Courier. Philadelphia, 1856‐1857. WorldCat: 2266075 Source: Viola. The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King. 1976. Source: WorldCat. 5. "Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Exhibit." Apollo (London, England) New Series 92(December 1970): 492. Notes: Source: Art Abstracts on OhioLINK. 6. Annals of Iowa (Des Moines) [Microform] 3rd Series, Vol. 1(1895). Notes: Source: Horan. The McKenney‐Hall Portrait Gallery of American Indians. 1986. Source: WorldCat. Source: RLIN. 7. Biographical Portraits of 108 Native Americans: Based on History of the Indian Tribes of North America, by Thomas L. McKenney and James Hall. Stamford, Connecticut: U.S. Games Systems, 1999. Notes: Source: WorldCat. 8. Boston Evening Transcript [Microform] (Boston, Massachusetts). Notes: Source: Horan. The McKenney‐Hall Portrait Gallery of American Indians. 1986. Source: WorldCat. 9. Catalogue of Works by The Late Henry Inman, With a Biographical Sketch: Exhibition for the Benefit of His Widow and Family, at the Art Union Rooms, No. -

Ansel Adams and American Landscapes at LI Museum March 5, 2015 by STEVE PARKS / [email protected] We Don't Think of Landscape Artists As Contentious

Newsday.com 4/13/2015 http://www.newsday.com/entertainment/long- island/museums/ansel-adams-and-american-landscapes-at-li- This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use onlym. Tuos eorudmer -p1r.e1s0en0t0a0tio3n6-2ready Reprints copies for distribution to colleagues, clients or customers, use the Reprints tool at the top of any article or order a reprint of this article now. Ansel Adams and American landscapes at LI Museum March 5, 2015 by STEVE PARKS / [email protected] We don't think of landscape artists as contentious. We associate their art with tranquillity. But as the pairing of new exhibits at the Long Island Museum suggests, some landscape artists have considered each other's testaments to nature either slavishly realistic or simplistically abstract. We see the objects of these debates in "Ansel Adams: Early Works" and "American Horizon, East to West." Spanning 150 years and 115 images captured through the lens or by the brush stroke, the two shows stretch the limits of the main galleries of LIM's Art Museum and the side gallery usually reserved for selections from its William Sidney Mount collection. As curator Joshua Ruff notes, Adams -- best known for black-and-white photographs of majestic American West scenes -- was often compared to the wildly successful 19th century painter Albert Bierstadt. "Adams disliked being referred to as painterly," Ruff says. "He thought painters manipulated nature. To him, photography was more truthful -- even though he manipulated in his own way through filters and printing techniques." ENLIGHTENED A light filter figured prominently in one of Adams' most iconic photographs, "Monolith, the Face of Half-Dome," 1927, separating the dark Yosemite sky from the black mountain face. -

Download Download

TEMPERANCE, ABOLITION, OH MY!: JAMES GOODWYN CLONNEY’S PROBLEMS WITH PAINTING THE FOURTH OF JULY Erika Schneider Framingham State College n 1839, James Goodwyn Clonney (1812–1867) began work on a large-scale, multi-figure composition, Militia Training (originally Ititled Fourth of July ), destined to be the most ambitious piece of his career [ Figure 1 ]. British-born and recently naturalized as an American citizen, Clonney wanted the American art world to consider him a major artist, and he chose a subject replete with American tradition and patriotism. Examining the numer- ous preparatory sketches for the painting reveals that Clonney changed key figures from Caucasian to African American—both to make the work more typically American and to exploit the popular humor of the stereotypes. However, critics found fault with the subject’s overall lack of decorum, tellingly with the drunken behavior and not with the African American stereotypes. The Fourth of July had increasingly become a problematic holi- day for many influential political forces such as temperance and abolitionist groups. Perhaps reflecting some of these pressures, when the image was engraved in 1843, the title changed to Militia Training , the title it is known by today. This essay will pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 77, no. 3, 2010. Copyright © 2010 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 14:57:03 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PAH77.3_02Schneider.indd 303 6/29/10 11:00:40 AM pennsylvania history demonstrate how Clonney reflected his time period, attempted to pander to the public, yet failed to achieve critical success. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1980, Volume 75, Issue No. 4

Maryland •listorical Magazine ublished Quarterly by The Museum and Library of Maryland History The Maryland Historical Society Winter 1980 THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS J. Fife Symington, Jr., Chairman* Robert G. Merrick, Sr., Honorary Chairman* Leonard C. Crewe, Jr., Vice Chairman* Frank H. Weller, Jr., President* J. Dorsey Brown, III, Vice President* Stuart S. Janney, III, Secretary* Mrs. Charles W. Cole, Jr., Vice President* John G. Evans, Treasurer* E. Phillips Hathaway, Vice President* J. Frederick Motz, Counsel* William C. Whitridge, Vice President* Samuel Hopkins, Past President* 'The officers listed above constitute the Society's Executive Committee. BOARD OF TRUSTEES H. Furlong Baldwin Richard R. Kline Frederick Co. Mrs. Emory J. Barber St. Mary's Co. Mrs. Frederick W. Lafferty Gary Black, Jr. John S. Lalley James R. Herbert Boone {Honorary) Charles D. Lyon Washington Co. Thomas W. Burdette Calvert C. McCabe, Jr. Philip Carroll Howard Co. Robert G. Merrick, Jr. Mrs. James Frederick Colwill Michael Middleton Charles Co. Owen Daly, II J. Jefferson Miller, II Donald L. DeVries W. Griffin Morrel Emory Dobson Caroline Co. Richard P. Moran Montgomery Co. Deborah B. English Thomas S. Nichols Charles O. Fisher Carroll Co. Addison V. Pinkney Mrs. Jacob France {Honorary) J. Hurst Purnell, Jr. Kent Co. Louis L. Goldstein Culvert Co. George M. Radcliffe Anne L. Gormer Allegany Co. Adrian P. Reed Queen Anne's Co. Kingdon Gould, Jr. Howard Co. Richard C. Riggs, Jr. William Grant Garrett Co. David Rogers Wicomico Co. Benjamin H. Griswold, III Terry M. Rubenstein R. Patrick Hayman Somerset Co. John D. Schapiro Louis G. Hecht Jacques T. -

Fond Du Lac Treaty Portraits: 1826

Fond du Lac Treaty Portraits: 1826 RICHARD E. NELSON Duluth, Minnesota The story of the Fond du Lac Treaty portraits began on the St. Louis River at a site near the present city of Duluth with these words: Whereas a treaty between the United States of America and the Chippeway tribe of Indians, was made and concluded on the fifth day of August, one thousand eight hundred and twenty-six, at the Fond du Lac of Lake Superior, in the territory of Michigan, by Commissioners on the part of the United States, and certain Chiefs and Warriors of the said tribe . (McKenney 1959:479) The location was memorialized by a monument erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution, Duluth, Minnesota, on November 21, 1922, which reads: Fond du Lac, Minnesota. Site of an Ojibway village from the earliest known pe riod. Daniel Greysolon Sieur de Lhut was here in 1679. Astor's American Fur Company established a trading post on this spot about 1817. First Ojibway treaty in Minnesota made here in 1826. The report of the treaty is recorded in Sketches of a Tour to the Lakes, of the Character and Customs of the Chippeway Indians, and of Incidents Connected with the Treaty of Fond du Lac written by Thomas K. McKenney in the form of letters to Secretary of War James Barbour in Washington and first published in 1827. McKenney was the head of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. In May of 1826 he and Lewis Cass, the governor of the Michigan Territory, were appointed by President John Quincy Adams to conclude a major treaty at Fond du Lac.