Transforming Ancestral Shadows Into Spiritual Activism Lorraine E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pop Culture, Including at the Stateof Race in of Catch-Up? Gqlooks Just Playing Aslow Game Narrowing, Or Are We Racial Gapinhollywood Lena Dunham

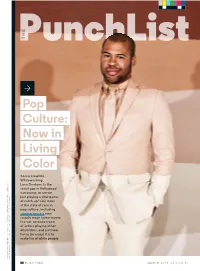

THE > Pop Culture: Now in Living Color #oscarssowhite. Whitewashing. Lena Dunham. Is the racial gap in Hollywood narrowing, or are we just playing a slow game of catch-up? GQ looks at the state of race in pop culture, including JORDAN PEELE’S new racially tense horror movie, the not-so-woke trend of actors playing other ethnicities, and just how funny (or scary) it is to make fun of white people STYLIST: MICHAEL NASH. PROP STYLIST: FAETHGRUPPE. GROOMING: HEE SOO SOO HEE GROOMING: FAETHGRUPPE. STYLIST: PROP NASH. MICHAEL STYLIST: KLEIN. CALVIN TIE: AND SHIRT, SUIT, GOETZ. + MALIN FOR KWON PETER YANG MARCH 2017 GQ. COM 81 THEPUNCHLIST Jordan Peele Is Terrifying The Key & Peele star goes solo with a real horror story: being black in America jordan peele’s directorial debut, Get Out, is the story of a black man who visits the family of his white girlfriend and begins to suspect they’re either a little racist or plotting to annihilate him. Peele examined race for laughs on the Emmy-winning series Key & Peele. But Get Out expresses racial tension in a way we’ve never seen before: as the monster in a horror Why do you think that is? the layer of race that enriches flick. caity weaver EGG ON YOUR talked to Peele in his Black creators have not been and complicates that tension given a platform, and the [in Get Out] becomes relatable. (BLACK)FACE editing studio about African-American experience An index of racially using race as fodder for can only be dealt with by My dad is a black guy from questionable role-playing a popcorn thriller and an African-American. -

Table of Contents 67

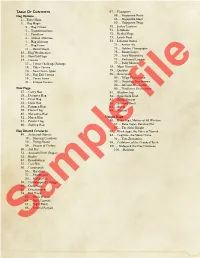

Table Of Contents 67 . Hagspawn Hag Options 68 . Hagspawn Brute 2 . Elder Hags 68 . Hagspawn Mage 3 . Hag Magic 69 . Hagspawn Thug 3 . Hag Curses 70 . Jack o' Lantern 4 . Transformations 71 . Jermlaine 4 . Familiars 72 . Kenku Mage 4 . Animal Affinities 73 . Leech Toad 4 . Hag Alchemy 74 . Libation Oozes 7 . Hag Items 74 . Amber Ale 11 . Weird Magic 75 . Golden Champagne 15 . Hag Weaknesses 75 . Ebony Lager 16 . Non-Evil Hags 75 . Ivory Moonshine 17 . Covens 77 . Perfumed Liqueur 17 . Coven Challenge Ratings 77 . Ruby Merlot 18 . Elder Covens 78 . Moor Hound 18 . New Coven Types 79 . Quablyn 19 . Non-Evil Covens 80 . Scarecrow 19 . Coven Items 80 . Effigy Scarecrows 21 . Unique Covens 80 . Guardian Scarecrows 80 . Infernal Scarecrow New Hags 80 . Pestilence Scarecrows 27 . Carey Hag 81 . Shadow Asp 29 . Deemves Hag 82 . Sporeback Toad 31 . Deep Hag 82 . Stirge Swarm 33 . Dusk Hag 83 . Stitched Devil 35 . Fanggen Hag 84 . Styrix 38 . Hocus Hag 85 . Wastrel 40 . Marzanna Hag 42 . Mojan Hag Unique Hags 44 . Powler Hag 86 . Baba Yaga, Mother of All Witches 46 . Sighing Hag 87 . Baba Yaga's Dancing Hut 87 . The Solar Knight Hag Related Creatures 90 . Black Agga, the Voice of Vaprak 49 . Animated Objects 93 . Cegilune, the Moon Crone 49 . Dancing Cauldron 96 . Yaya Zhelamiss 50 . Flying Spoon 98 . Ceithlenn, of the Crooked Teeth 50 . Swarm of Cutlery 101 . Malagard, the Hag Countess 50 . Ash Rat 106 . Kalabon 52 . Assassin Devil (Dogai) 53 . Boglin 54 . Broodswarm 55 . Cait Sith 56 . Canomorph 56 . Haraknin 57 . Shadurakul 58 . Yeshbavhan 59 . Catobleopas Harbinger 60 . -

Gambling in the Mid-Nineteenth-Century Latin American Social Imaginary

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository GAMBLING IN THE MID-NINETEENTH-CENTURY LATIN AMERICAN SOCIAL IMAGINARY Emily Joy Clark A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies (Spanish). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Rosa Perelmuter Juan Carlos González Espitia Emilio del Valle Escalante Irene Gómez Castellano John Charles Chasteen © 2016 Emily Joy Clark ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Emily Joy Clark: Gambling in the Mid-Nineteenth-Century Latin American Social Imaginary (Under the direction of Rosa Perelmuter) Economic themes appear in many nineteenth-century Latin American narratives, but the representation of gambling and other forms of speculative capitalist commerce, such as investment, trade, and mining, is a largely unexplored area of critical literary analysis. This dissertation examines the depiction of gambling and other games of chance, as well as financially-speculative endeavors, in eight texts from the mid-nineteenth century throughout Hispanic America, including José Joaquín Fernández de Lizardi’s El Periquillo Sarniento (1816), Eduardo Gutiérrez’s Juan Moreira (1879), Rosario Orrego’s Alberto el jugador (1860), Teresa González de Fanning’s Regina (1886), Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda’s Sab (1841), Alberto Blest Gana’s Martín Rivas (1862), José Ramón de Betancourt’s Una feria de la caridad en 183… (1841, 1858), and José Milla’s Los Nazarenos (1867). In the four chapters of the dissertation, I analyze four different perspectives on gambling and its repercussions in society as it applies to gender (Chapters 1 and 2), social class (Chapter 3), and the role of the citizen in post-independence Latin American nation states (Chapter 4). -

Notre Dame Scholastic, Vol. 102, No. 11

a c/> c/> The most famous names in American men's wear are here for you: Eagle, Society Brand, GGG, Hickey-Freeman, Burberry, Alligator, 'Botany' 500, Alpagora, Arrow, Hathaway, Swank, McGregor, Bemhard Altmann, Dobbs, Florsheim . and many, many more. Truly the finest men's clothing and furnishings ob tainable in today's world markets. On the Cmnfius—Notre Drnne o &&& ... so select what you need now: a new suit or topcoat for the holidays ahead . gifts for special friends, and charge them the Campus Shop way. By the way, the Campus Shop will give you quick, expert fitting service so that what you purchase now will be altered and ready before. you leave the campus for the holidays. Merry Christmas and Happy New Year! CHARGE IT THE CAMPUS SHOP WAY 1/3 1/3 IN JUNE IN JULY No Carrying Charge ^ILBERrS On the Campus—Notre Dune Kttfa QaCampis MsShoIman (Author of "I Was a Teen-age Dwarf", "The Manii Loves of Dobie Gillis", etc.) DECK THE HALLS The time has come to make out our Robespierre, alas, was murdered quicker Inarticulate Society Christmas shopping lists, for Christmas than 3'ou could shout Jacques Robes Editor: %\-iU be upon us quicker than you can saj' pierre (or Jack Robinson as he is called Mr. Hudson, in last w^eek's Reper cussions, took issue with Mr. Smith's Jack Robinson. (Have j'ou ever won in the English-speaking countries). hierarchical theory of government: it dered, incidentall}--, about the origin of (There is, I am pleased to report, one was Mr. -

De-Demonising the Old Testament

De-Demonising the Old Testament An Investigation of Azazel , Lilith , Deber , Qeteb and Reshef in the Hebrew Bible Judit M. Blair Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh 2008 Declaration I declare that the present thesis has been composed by me, that it represents my own research, and that it has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. ______________________ Judit M. Blair ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people to thank and acknowledge for their support and help over the past years. Firstly I would like to thank the School of Divinity for the scholarship and the opportunity they provided me in being able to do this PhD. I would like to thank my ‘numerous’ supervisors who have given of their time, energy and knowledge in making this thesis possible: To Professor Hans Barstad for his patience, advice and guiding hand, in particular for his ‘adopting’ me as his own. For his understanding and help with German I am most grateful. To Dr Peter Hayman for giving of his own time to help me in learning Hebrew, then accepting me to study for a PhD, and in particular for his attention to detail. To Professor Nick Wyatt who supervised my Masters and PhD before his retirement for his advice and support. I would also like to thank the staff at New College Library for their assistance at all times, and Dr Jessie Paterson and Bronwen Currie for computer support. My fellow colleagues have provided feedback and helpful criticism and I would especially like to thank all members of HOTS-lite I have known over the years. -

Doru Div Spells

Doru Div Spells word answer would be misleading or contrary to Charm Person (DC 13) 3/day the deity’s interests, a short phrase (five words School enchantment (charm) [mind-affecting]; or less) may be given as an answer instead. Level bard 1, sorcerer/wizard 1 The spell, at best, provides information Casting Time 1 standard action to aid character decisions. The entities Components V, S contacted structure their answers to further their Range close (25 ft. + 5 ft./2 levels) own purposes. If you lag, discuss the answers, Target one humanoid creature or go off to do anything else, the spell ends. Duration 1 hour/level Saving Throw Will negates; Spell Resistance yes Detect Good Constant This charm makes a humanoid creature regard you as its trusted friend and ally (treat the Detect Magic target’s attitude as friendly). If the creature is Constant currently being threatened or attacked by you or your allies, however, it receives a +5 bonus on Invisibility (self only At Will) its saving throw. School illusion (glamer); Level bard 2, The spell does not enable you to control sorcerer/wizard 2 the charmed person as if it were an automaton, Casting Time 1 standard action but it perceives your words and actions in the Components V, S, M/DF (an eyelash encased most favorable way. You can try to give the in gum arabic) subject orders, but you must win an opposed Range personal or touch Charisma check to convince it to do anything it Target you or a creature or object weighing no wouldn’t ordinarily do. -

1401882258184.Pdf

The Witch A New Class for Basic Era Games by Timothy S. Brannan Copyright © 2012 Proofreading and editing by and Jeffrey Allen and James G Holloway, DBA Dark Spire. Artists: Daniel Brannan Brian Brinlee Gary Dupuis Larry Elmore Toby Gregory Aitor Gonzalez William McAusland Bradley K McDevitt Bree Orlock and Stardust Publications Howard Pyle Artwork copyright by the original artist and used with permission. Some artwork is in the public domain. Cover art by John William Waterhouse 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................. 2 Athamé .................................................................................78 Forward ................................................................................ 3 Broom ..................................................................................78 PART 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................... 5 Cauldron ...............................................................................78 PART 2: THE WITCH CLASS ............................................ 7 Censer ..................................................................................79 Special Restrictions (Optional) ............................................. 8 Chalice .................................................................................79 Witch ................................................................................. 9 Pentacle ................................................................................79 PART 3: TRADITIONS -

Cnow: Eldritch Witchery

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition The Complete Netbook of Witches & Warlocks: Eldritch Witchery Supplement I 1 The Complete Netbook of Witches and Warlocks: Eldritch Witchery Forward Welcome to the first supplement to the Complete Netbook of Witches and Warlocks. This supplement will contain new ideas, revised old ones, and some extra things I thought you might enjoy. It took me close to 10 years to start and then finish my first netbook. Hopefully this one will not take as long. To begin with, none of the information in this volume is necessary or required to continue to play your witch characters. There is some additional information and errata, but most will be new information. Also there will be some information that is not necessarily witch related, but designed to add extra background to the worlds the witch is likely to play in. This supplement pays homage to the Original Dungeons and Dragons game supplement Eldritch Wizardry. That supplement introduced demons, psionics, artifacts and druids to the D&D game for the first time. It also was the first D&D product that came close to being banned. The controversial cover art, a nude blond woman bound up for a sacrifice, made this a rare item to find. Eldritch Witchery, which conversely has no cover art, will not be as rare or as collectable, but hopefully it will provide you with as much fun as the first provided me. Copies of this supplement, the original Complete Netbook of Witches and Warlocks, as well as any future supplements can be found at my website at http://www.rpghost.com/WebWarlock or http://go.to/WebWarlock. -

311808-Sample.Pdf

Sample. file Contents Author Notes and Credits ......................................4 Chapter 7: Potions of 54 Chapter 1: Hags in General 7 Mutation Randomly Found Potions of Mutation ...............................54 Hag Covens ................................................................................9 Mutation Potion Generator ..................................................55 Cegilune ....................................................................................11 Hag Tailor Made Potions of Mutation ................................56 The Immortal Three ..............................................................12 Sister Sepia & The Burning Bright ....................................14 Chapter 8: Hag Weirds 58 Chapter 2: Hags Lairs 16 Known Hag Weirds ................................................................58 Hag Lairs Near Civilization ..................................................16 68 Herbalist Cottage or Shop ....................................................17 Chapter 9: New Spells Large Active Graveyard .........................................................18 Spell List ...................................................................................70 Sewer or Dungeon .................................................................18 Spell Descriptions ..................................................................71 Haunted House .......................................................................19 Hag Lairs in the Wilderness ................................................ 19 Chapter -

Dreaming of Dwarves

DREAMING OF DWARVES: NIGHTMARES AND SHAMANISM IN ANGLO-SAXON POETICS AND THE WIĐ DWEORH CHARM by MATTHEW C. G. LEWIS (Under the Direction of Jonathan Evans) ABSTRACT Anglo-Saxon Metrical Charm 3, Wið Dweorh, from the British Library MS Harley 585, provides evidence of remnants of shamanic thinking in the early Christian era of Anglo-Saxon England. It shows a depth of understanding of dream psychology that prefigures modern psychiatric techniques; provides clues as to the linguistic, religious, cultural, and folkloric origins of nightmares, and reflects a tradition of shamanism in Old English poetry. This paper illustrates these linguistic and folkloric themes, places the metrical charm within the shamanistic tradition of Old English poetics, and connects the charm‟s value as a therapeutic device to modern psychiatric techniques. INDEX WORDS: Anglo-Saxon poetics, shamanism, metrical charms, nightmare, dreams, folk medicine and remedies, The Wanderer, Lacnunga, The Seafarer, Beowulf, medieval folklore, succubus, theories of cognition, psychiatry DREAMING OF DWARVES ANGLO-SAXON DREAM THEORY, NIGHTMARES, AND THE WIĐ DWEORH CHARM by MATTHEW C. G. LEWIS A.B., University of Georgia, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Matthew C. G. Lewis All Rights Reserved DREAMING OF DWARVES ANGLO-SAXON DREAM THEORY, NIGHTMARES, AND THE WIĐ DWEORH CHARM by MATTHEW C. G. LEWIS Major Professor: Jonathan Evans Committee: Charles Doyle John Vance Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2009 iv DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my parents, Brian and Kate Lewis, who instilled in me an early love of reading; and who have uncomplainingly put up with far too many years of my academic puttering about; and to my aunt, Thérèse Lewis, who introduced me to J. -

KLIO Penn State's Creative Arts Journal Volume 3, 2018

KLIO Penn State’s Creative Arts Journal Volume 3, 2018 OUR MISSION Klio is the Muse of history and poetry, called upon by early Greek writers and artists for inspiration and creative guidance. The Greek verb kleô, meaning to celebrate, comes from her name. Here at Klio, we celebrate both written and visual expressions of creativity. Klio is the online sister to Penn State’s creative arts journal, Kalliope. Klio seeks to showcase the work of students and keep a community record of creative arts from all PSU campuses. We strive to provide an inclusive community to celebrate the creative and linguistic talents of emerging Penn State artists and writers. Any and all forms are encouraged, as we pride ourselves on being a multimedia publication that represents diversity in art, perspective, and culture. Klio is a platform for all Penn State students. We are Penn State. We are Klio. Cover art: “See Me” by Joy Blazofsky Klio Logo by Sarah Nields KLIO 2018| klio.psu.edu 1 KLIO 2018 STAFF Editor-in-Chief: Tiffany Fu Managing Editor: Christy McDermott Fiction Editor: Nathan Ousey Poetry Editor: Sumner C. Drain V Non-Fiction Editor: Erin Campbell Art and Multimedia Director: Sean Bradley Music Editor: Maddy Bacon Curatorial Editor: Grace Eppinger Blog Editors: Grace Eppinger | Christy McDermott Promotion/Marketing: Adam Traina Social Media Coordinators: Sam Cavanagh | Erin Campbell Social Events Coordinator/University Park Outreach: Kayla White Commonwealth Campus Coordinator/International Student Outreach: Jinny Kim Web Developers: Katherine Reese | Taylor Hayes Archive Manager: Taylor Hayes Faculty Advisor: Alison Jaenicke KLIO 2018| klio.psu.edu 2 Dear Klio Readers, As we near the end of the fall semester, our Klio staff would like to thank our contributors and readers, and bid farewell to the publication we’ve been busy building over the past few months. -

Truth and Salsa Truth and Salsa

Middle reader fiction www.peachtree-online.com allssaa n Mexico, everyone calls thirteen-year-old gringa a I lOWErY SS Hayley by the new name she has chosen: Margarita. andand Life includes endless fireworks, beautiful butterflies, hh colorful fiestas, a mysterious ghost, and even a tt glamorous part as a movie extra with her new friend, uu Truth and Salsa Lili. Hayley’s having so much fun, she almost forgets about Truth and Salsa rr her parents’ recent separation. TT But there are also difficult lessons to be learned, as poverty forces Lili’s father and other men from the village to work as migrant laborers in the United States. When they encounter hardship and prejudice, Hayley begins to understand the true meaning of family unity… Awards and Praise for TruTh And SAlSA “Hayley is a refreshing heroine, warm and realistic… The writing is engaging, and Lowery has created a strong sense of place through vivid descriptions of local festivals, scenery, and day-to-day life in the town.” —School Library Journal ✱ ISBN 13: 978-1-56145-498-3 2007 Bank Street College of Education Best Children’s Books ISBN 10: 1-56145-498-2 of the Year ✱ 2006 Society of School Librarians International Book Awards LINDA LOWERY (honor book, Language Arts K-6) ✱ 2007 Kansas State Reading Circle (Middle School) / Kansas National Education Association Truth and Salsa Truth and Salsa LINDA LOWERY Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2006 by Linda Lowery First trade paperback edition published in 2009 All rights reserved.