Creatures in the Mist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOS DUENDES EN LA LITERATURA ESPAÑOLA Manuel

REVISTA GAROZA Nº 10. SEPTIEMBRE 2010. ISSN: 1577-8932 LOS DUENDES EN LA LITERATURA ESPAÑOLA Manuel COUSILLAS RODRÍGUEZ I.E.S. Salvador de Madariaga. A Coruña RESUMEN Como seres mitológicos elementales de la naturaleza, guardianes de los bosques y de todos los seres vivos que habitan en ellos, los duendes forman parte de la raza elemental feérica, y junto con elfos, trols y hadas, son los seres más populares de las mitologías celta y nórdica. Según la mitología celta, el rey de los duendes y elfos responde al nombre de Oberón, mencionado en obras como Macbeth o Sueño de una noche de San Juan de William Shakespeare. Posteriormente, estas leyendas son igualmente mencionadas en el Fausto de Goethe, donde un coro de silfos invocado por Mefistófeles trata de seducir al doctor Fausto, o en cuentos tradicionales infantiles como los escritos por los hermanos Grimm, donde la figura del duende suele asociarse a pequeños seres bonachones. Herederos de esa tradición literaria son muchos de los cuentos contemporáneos del peninsular español. Palabras clave: duende, céltica, península ibérica, literatura comparada. ABSTRACT As a basic mythological element in our nature, guardians of forests and all living things that inhabit them, fairies are part of the elemental fairy race, and along with elves, and trolls, are the most popular creatures in Celtic and Norse mythologies. According to Celtic mythology, the king of fairies and elves is named Oberon, mentioned in works such as Macbeth or Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare. These legends are also mentioned in Goethe's 61 MANUEL COUSILLAS RODRÍGUEZ REVISTA GAROZA Nº 10. -

James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 474 132 SO 033 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty TITLE James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at Uplands Retirement Community (Pleasant Hill, TN, June 17, 2002). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; *Educational Background; Popular Culture; Primary Sources; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Conversation; Educators; Historical Research; *Michener (James A); Pennsylvania (Doylestown); Philanthropists ABSTRACT This paper presents an imaginary conversation between an interviewer and the novelist, James Michener (1907-1997). Starting with Michener's early life experiences in Doylestown (Pennsylvania), the conversation includes his family's poverty, his wanderings across the United States, and his reading at the local public library. The dialogue includes his education at Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), St. Andrews University (Scotland), Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) where he became a social studies teacher, and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts) where he pursued, but did not complete, a Ph.D. in education. Michener's experiences as a textbook editor at Macmillan Publishers and in the U.S. Navy during World War II are part of the discourse. The exchange elaborates on how Michener began to write fiction, focuses on his great success as a writer, and notes that he and his wife donated over $100 million to educational institutions over the years. Lists five selected works about James Michener and provides a year-by-year Internet search on the author.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Pop Culture, Including at the Stateof Race in of Catch-Up? Gqlooks Just Playing Aslow Game Narrowing, Or Are We Racial Gapinhollywood Lena Dunham

THE > Pop Culture: Now in Living Color #oscarssowhite. Whitewashing. Lena Dunham. Is the racial gap in Hollywood narrowing, or are we just playing a slow game of catch-up? GQ looks at the state of race in pop culture, including JORDAN PEELE’S new racially tense horror movie, the not-so-woke trend of actors playing other ethnicities, and just how funny (or scary) it is to make fun of white people STYLIST: MICHAEL NASH. PROP STYLIST: FAETHGRUPPE. GROOMING: HEE SOO SOO HEE GROOMING: FAETHGRUPPE. STYLIST: PROP NASH. MICHAEL STYLIST: KLEIN. CALVIN TIE: AND SHIRT, SUIT, GOETZ. + MALIN FOR KWON PETER YANG MARCH 2017 GQ. COM 81 THEPUNCHLIST Jordan Peele Is Terrifying The Key & Peele star goes solo with a real horror story: being black in America jordan peele’s directorial debut, Get Out, is the story of a black man who visits the family of his white girlfriend and begins to suspect they’re either a little racist or plotting to annihilate him. Peele examined race for laughs on the Emmy-winning series Key & Peele. But Get Out expresses racial tension in a way we’ve never seen before: as the monster in a horror Why do you think that is? the layer of race that enriches flick. caity weaver EGG ON YOUR talked to Peele in his Black creators have not been and complicates that tension given a platform, and the [in Get Out] becomes relatable. (BLACK)FACE editing studio about African-American experience An index of racially using race as fodder for can only be dealt with by My dad is a black guy from questionable role-playing a popcorn thriller and an African-American. -

Elemental Motes by Charles Choi Illustration by Rob Alexamder Little Fires up the Imagination More Than a Vision of the Well

Fantastic Terrain: Elemental Motes By Charles Choi illustration by Rob Alexamder Little fires up the imagination more than a vision of the well. The awe-inspiring heights that motes often soar at carry impossible, such as an island defying gravity by floating miles the promise of death-defying acts of derring-do that can stick high up in the air. This might be why castles in the sky are so with players for years. Although the constant risk of a poten- common in fantasy, from the ethereal cloud kingdoms seen tially lethal fall underlies the greatest strength of motes as a in fairy tales such as Jack and the Beanstalk to the ominous storytelling tool—spine-tingling suspense—unfortunately, it is flying citadels of Krynn in Dragonlance. also their greatest weakness. One wrong step on the part of either Dungeon Master or player, and a player character or Islands in the sky made their debut in 4th Edition as valuable nonplayer character can inadvertently go hurtling earthmotes in the updated Forgotten Realms® setting, and into the brink. However, such challenges can be overcome now they can be unforgettable elements in your campaign as easily with a little forethought. TM & © 2009 Wizards of the Coast LLC All rights reserved. March 2010 | Dungeon 176 76 Fantastic Terrain: Elemental Motes Motes in On the flipside, in settings where air travel is common, such as the Eberron® setting, motes Facts abouT Motes Your CaMpaign could become common ports of call. Such mote- Motes are often born from breaches between the ports can brim with adventure and serve as home mortal world and the Elemental Chaos, when matter In a game that includes monster-infested dungeons, to all kinds of intrigue. -

'Goblinlike, Fantastic: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40443/ Version: Full Version Citation: Fergus, Emily (2019) ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email ‘Goblinlike, Fantastic’: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle Emily Fergus Submitted for MPhil Degree 2019 Birkbeck, University of London 2 I, Emily Fergus, confirm that all the work contained within this thesis is entirely my own. ___________________________________________________ 3 Abstract This thesis offers a new reading of how little people were presented in both fiction and non-fiction in the latter half of the nineteenth century. After the ‘discovery’ of African pygmies in the 1860s, little people became a powerful way of imaginatively connecting to an inconceivably distant past, and the place of humans within it. Little people in fin de siècle narratives have been commonly interpreted as atavistic, stunted warnings of biological reversion. I suggest that there are other readings available: by deploying two nineteenth-century anthropological theories – E. B. Tylor’s doctrine of ‘survivals’, and euhemerism, a model proposing that the mythology surrounding fairies was based on the existence of real ‘little people’ – they can also be read as positive symbols of the tenacity of the human spirit, and as offering access to a sacred, spiritual, or magic, world. -

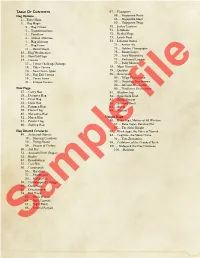

Table of Contents 67

Table Of Contents 67 . Hagspawn Hag Options 68 . Hagspawn Brute 2 . Elder Hags 68 . Hagspawn Mage 3 . Hag Magic 69 . Hagspawn Thug 3 . Hag Curses 70 . Jack o' Lantern 4 . Transformations 71 . Jermlaine 4 . Familiars 72 . Kenku Mage 4 . Animal Affinities 73 . Leech Toad 4 . Hag Alchemy 74 . Libation Oozes 7 . Hag Items 74 . Amber Ale 11 . Weird Magic 75 . Golden Champagne 15 . Hag Weaknesses 75 . Ebony Lager 16 . Non-Evil Hags 75 . Ivory Moonshine 17 . Covens 77 . Perfumed Liqueur 17 . Coven Challenge Ratings 77 . Ruby Merlot 18 . Elder Covens 78 . Moor Hound 18 . New Coven Types 79 . Quablyn 19 . Non-Evil Covens 80 . Scarecrow 19 . Coven Items 80 . Effigy Scarecrows 21 . Unique Covens 80 . Guardian Scarecrows 80 . Infernal Scarecrow New Hags 80 . Pestilence Scarecrows 27 . Carey Hag 81 . Shadow Asp 29 . Deemves Hag 82 . Sporeback Toad 31 . Deep Hag 82 . Stirge Swarm 33 . Dusk Hag 83 . Stitched Devil 35 . Fanggen Hag 84 . Styrix 38 . Hocus Hag 85 . Wastrel 40 . Marzanna Hag 42 . Mojan Hag Unique Hags 44 . Powler Hag 86 . Baba Yaga, Mother of All Witches 46 . Sighing Hag 87 . Baba Yaga's Dancing Hut 87 . The Solar Knight Hag Related Creatures 90 . Black Agga, the Voice of Vaprak 49 . Animated Objects 93 . Cegilune, the Moon Crone 49 . Dancing Cauldron 96 . Yaya Zhelamiss 50 . Flying Spoon 98 . Ceithlenn, of the Crooked Teeth 50 . Swarm of Cutlery 101 . Malagard, the Hag Countess 50 . Ash Rat 106 . Kalabon 52 . Assassin Devil (Dogai) 53 . Boglin 54 . Broodswarm 55 . Cait Sith 56 . Canomorph 56 . Haraknin 57 . Shadurakul 58 . Yeshbavhan 59 . Catobleopas Harbinger 60 . -

Horse Motifs in Folk Narrative of the Supernatural

HORSE MOTIFS IN FOLK NARRATIVE OF THE SlPERNA TURAL by Victoria Harkavy A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ___ ~C=:l!L~;;rtl....,19~~~'V'l rogram Director Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: ~U_c-ly-=-a2..!-.:t ;LC>=-----...!/~'fF_ Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Horse Motifs in Folk Narrative of the Supernatural A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Victoria Harkavy Bachelor of Arts University of Maryland-College Park 2006 Director: Margaret Yocom, Professor Interdisciplinary Studies Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to my wonderful and supportive parents, Lorraine Messinger and Kenneth Harkavy. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee, Drs. Yocom, Fraser, and Rashkover, for putting in the time and effort to get this thesis finalized. Thanks also to my friends and colleagues who let me run ideas by them. Special thanks to Margaret Christoph for lending her copy editing expertise. Endless gratitude goes to my family taking care of me when I was focused on writing. Thanks also go to William, Folklore Horse, for all of the inspiration, and to Gumbie, Folklore Cat, for only sometimes sitting on the keyboard. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract .............................................................................................................................. vi Interdisciplinary Elements of this Study ............................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

Meike Weijtmans S4235797 BA Thesis English Language and Culture Supervisor: Dr

Weijtmans, s4235797/1 Meike Weijtmans s4235797 BA Thesis English Language and Culture Supervisor: dr. Chris Cusack Examiner: dr. L.S. Chardonnens August 15, 2018 The Celtic Image in Contemporary Adaptations of the Arthurian Legend M.A.S. Weijtmans BA Thesis August 15, 2018 Weijtmans, s4235797/2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: dr. Chris Cusack, dr. L.S. Chardonnens Title of document: The Celtic Image in Contemporary Adaptations of the Arthurian Legend Name of course: BA Thesis Date of submission: August 15, 2018 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Meike Weijtmans Student number: s4235797 Weijtmans, s4235797/3 Abstract Celtic culture has always been a source of interest in contemporary popular culture, as it has been in the past; Greek and Roman writers painted the Celts as barbaric and uncivilised peoples, but were impressed with their religion and mythology. The Celtic revival period gave birth to the paradox that still defines the Celtic image to this day, namely that the rurality, simplicity and spirituality of the Celts was to be admired, but that they were uncivilised, irrational and wild at the same time. Recent debates surround the concepts of “Celt”, “Celticity” and “Celtic” are also discussed in this thesis. The first part of this thesis focuses on Celtic history and culture, as well as the complexities surrounding the terminology and the construction of the Celtic image over the centuries. This main body of the thesis analyses the way Celtic elements in contemporary adaptations of the Arthurian narrative form the modern Celtic image. -

The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2011 The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Dance Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Flores, Tania, "The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1118. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1118 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores Occidental College Migration and Transnational Identity: Fall 2011 Flores 2 Acknowledgments I could not have completed this project without the advice and guidance of my academic director, Professor Souad Eddouada; my advisor, Professor Taieb Belghazi; my professor of music at Occidental College, Professor Simeon Pillich; my professor of Islamic studies at Occidental, Professor Malek Moazzam-Doulat; or my gracious and helpful interviewees. I am also grateful to Elvira Roca Rey for allowing me to use her studio to choreograph after we had finished dance class, and to Professor Said Graiouid for his guidance and time. -

Magical Creatures in Isadora Moon

The Magical Creatures of Isadora Moon In the Isadora Moon stories, Isadora’s mum is a fairy and her dad is a vampire. This means that, even though Isadora lives in the human world, she has adventures with lots of fantastical creatures. Harriet Muncaster writes and draws the Isadora Moon books. Writers like Harriet often look at stories and legends from the past to get ideas for their own stories. What are some of the legends that Harriet looked at when telling the story of Isadora Moon, and what has she changed to make her stories as unique as Isadora herself? Fairies In the modern day, we picture fairies as tiny human-like creatures with wings like those of dragonflies or butterflies. However, up until the Victorian age (1837- 1901), the word ‘fairy’ meant any magical creature or events and comes from the Old French word faerie, which means ‘enchanted’. Goblins, pixies, dwarves and nymphs were all called ‘fairies’. These different types of fairies usually did not have wings, and were sometimes human- sized instead of tiny. They could also be good or bad, either helping or tricking people. Luckily, Isadora’s mum, Countess Cordelia Moon, is a good fairy, who likes baking magical cakes, planting colourful flowers, and spending time in nature. Like most modern fairies, she has wings, magical powers, and a close connection with nature, but unlike fairies in some stories, she is human-size. Isadora’s mum can fly using her fairy wings and can use her magic wand to bring toys to life, make plants grow anywhere, and change the appearance of different objects, such as Isadora’s tent. -

The Myths of Mexico and Peru

THE MYTHS OF MEXICO AND PERU by Lewis Spence (1913) This material has been reconstructed from various unverified sources of very poor quality and reproduction by Campbell M Gold CMG Archives http://campbellmgold.com --()-- 1 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Illustrations .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Map of the Valley of Mexico ................................................................................................................ 3 Ethnographic Map of Mexico ............................................................................................................... 4 Detail of Ethnographic Map of Mexico ................................................................................................. 5 Empire of the Incas .............................................................................................................................. 6 Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1 - The Civilisation of Mexico .................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 2 - Mexican Mythology ........................................................................................................... -

Aleksandr Nikoláevitch Afanássiev E O Conto Popular Russo

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS ORIENTAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LITERATURA E CULTURA RUSSA FLAVIA CRISTINA MOINO CAROLINSKI Aleksandr Nikoláevitch Afanássiev e o conto popular russo São Paulo 2008 UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS ORIENTAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LITERATURA E CULTURA RUSSA Aleksandr Nikoláevitch Afanássiev e o conto popular russo Flavia Cristina Moino Carolinski Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Literatura e Cultura Russa do Departamento de Letras Orientais da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Mestre. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Arlete Orlando Cavaliere São Paulo 2008 Agradecimentos À minha orientadora Profa. Dra. Arlete O. Cavaliere por sempre ter acreditado e incentivado meu trabalho. Aos Profs. Drs. Bruno Barreto Gomide e Elena N. Vássina por toda a pronta atenção dispensada durante o processo do trabalho. Aos Profs. Drs. Boris Schnaiderman e Serguei Nekliúdov pela generosidade com que me ajudaram a esclarecer diversos pontos da pesquisa. À amiga e professora Tatiana Larkina pela paciência e permanente apoio. A todos os meus amigos queridos que foram atormentados pelas minhas dúvidas eternas. Ao meu superespecial marido que, com carinho e inteligência, acompanhou atentamente cada passo deste trabalho. 3 Resumo A coletânea Contos populares russos, lançada de 1855 a 1863 em oito volumes, foi resultado do cuidadoso trabalho de Aleksandr N. Afanássiev (1826-1871), responsável pela reunião e publicação de cerca de 600 textos presentes nessa obra, que ganhou destaque por ser a primeira coletânea de contos populares russos de caráter científico, tornando-se assim um importante material de estudo, além de apresentar a poesia e o humor inerentes aos contos.