Dreaming of Dwarves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partners Early Music Vancouver Gratefully Acknowledges the Assistance and Support Of: GOVERNMENT SUPPORT Board of Directors

partners Early Music Vancouver gratefully acknowledges the assistance and support of: GOVERNMENT SUPPORT board of directors Fran Watters We acknowledge the support of president the Province of British Columbia Chris Guzy vice president Ron Kruschen treasurer FOUNDATIONS Ilia Korkh secretary THE BRENNAN SPANO FAMILY FOUNDATION Sherrill Grace THE DRANCE FAMILY Tony Knox EARLY MUSIC VANCOUVER FUND Melody Mason 2019-20 PRODUCTION PARTNERS Johanna Shapira Vincent Tan EMV’s performances at the Chan Centre are presented in partnership with the Chan Centre for the Performing Arts, with the support of the Chan Endowment Fund at the University of British Columbia. ÷ pacific José Verstappen cm baroque orchestra artistic director emeritus alexander weimann MUSIC director ÷ staff Matthew White executive & artistic director Nathan Lorch business manager Michelle Herrewynen resource development manager PRODUCTION PARTNERS IN VICTORIA BC Jonathan Evans production manager Laina Tanahara marketing & volunteer coordinator CORPORATE SUPPORT Jan Gates event photographer Rosedale on Robson Suite Hotel VANCOUVER, BC Tony Knox Barrister & Solicitor, Arbitrator Tel: 604 263 5766 Cell: 604 374 7916 Fax: 604 261 1868 Murray Paterson Email: [email protected] 1291 West 40th Avenue, Vancouver, B.C. V6M 1V3 Canada Marketing Group www.knoxlex.com We also gratefullyKnox & Co. denotes D.A.Knox Lawacknowledge Corporation the generosity of our many donors and volunteers. marketing & media relations Trevor Mangion thank you! and The Chan Centre Box Office Staff emv ticket office: 604.822.2697 You can be in good company too! The corporate sponsors of Early Music Vancouver give back to their community through the support of our performances and education & outreach programmes. Their efforts 1254 West 7th Avenue, make a meaningful difference for concertgoers and musicians alike. -

The Cambridge Old English Reader

The Cambridge Old English Reader RICHARD MARSDEN School of English Studies University of Nottingham published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org c Cambridge University Press 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Times 10/13 pt System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Marsden, Richard. The Cambridge Old English reader / Richard Marsden. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0 521 45426 3 (hardback) – ISBN 0 521 45612 6 (paperback) 1. English language – Old English, ca. 450–1100 – Readers. 2. Anglo-Saxons – Literary collections. 3. Anglo-Saxons – Sources. I. Title. PE137.M46 2003 429.86421–dc21 2003043579 ISBN 0 521 45426 3 hardback ISBN 0 521 45612 6 paperback Contents Preface page ix List of abbreviations xi Introduction xv The writing and pronunciation -

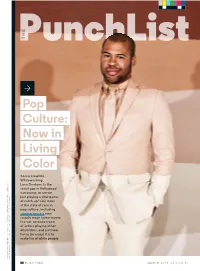

Pop Culture, Including at the Stateof Race in of Catch-Up? Gqlooks Just Playing Aslow Game Narrowing, Or Are We Racial Gapinhollywood Lena Dunham

THE > Pop Culture: Now in Living Color #oscarssowhite. Whitewashing. Lena Dunham. Is the racial gap in Hollywood narrowing, or are we just playing a slow game of catch-up? GQ looks at the state of race in pop culture, including JORDAN PEELE’S new racially tense horror movie, the not-so-woke trend of actors playing other ethnicities, and just how funny (or scary) it is to make fun of white people STYLIST: MICHAEL NASH. PROP STYLIST: FAETHGRUPPE. GROOMING: HEE SOO SOO HEE GROOMING: FAETHGRUPPE. STYLIST: PROP NASH. MICHAEL STYLIST: KLEIN. CALVIN TIE: AND SHIRT, SUIT, GOETZ. + MALIN FOR KWON PETER YANG MARCH 2017 GQ. COM 81 THEPUNCHLIST Jordan Peele Is Terrifying The Key & Peele star goes solo with a real horror story: being black in America jordan peele’s directorial debut, Get Out, is the story of a black man who visits the family of his white girlfriend and begins to suspect they’re either a little racist or plotting to annihilate him. Peele examined race for laughs on the Emmy-winning series Key & Peele. But Get Out expresses racial tension in a way we’ve never seen before: as the monster in a horror Why do you think that is? the layer of race that enriches flick. caity weaver EGG ON YOUR talked to Peele in his Black creators have not been and complicates that tension given a platform, and the [in Get Out] becomes relatable. (BLACK)FACE editing studio about African-American experience An index of racially using race as fodder for can only be dealt with by My dad is a black guy from questionable role-playing a popcorn thriller and an African-American. -

The Inscription of Charms in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts

Oral Tradition, 14/2 (1999): 401-419 The Inscription of Charms in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts Lea Olsan Anglo-Saxon charms constitute a definable oral genre that may be distinguished from other kinds of traditionally oral materials such as epic poetry because texts of charms include explicit directions for performance. Scribes often specify that a charm be spoken (cwean) or sung (singan). In some cases a charm is to be written on some object. But inscribing an incantation on an object does not necessarily diminish or contradict the orality of the genre. An incantation written on an amulet manifests the appropriation of the technology of writing for the purposes of a traditionally oral activity.1 Unlike epic poetry, riddles, or lyrics, charms are performed toward specific practical ends and their mode of operation is performative, so that uttering the incantation accomplishes a purpose. The stated purpose of an incantation also determines when and under what circumstances a charm will be performed. Charms inscribed in manuscripts are tagged according to the needs they answer-whether eye pain, insomnia, childbirth, theft of property, or whatever. Some charms ward off troubles (toothache, bees swarming); others, such as those for bleeding or swellings, relieve physical troubles. This specificity of purpose markedly distinguishes the genre from other traditional oral genres that are less specifically utilitarian. Given the specific circumstances of need that call for their performance, the social contexts in which charms are performed create the conditions felicitous for performative speech acts in Austin’s sense (1975:6-7, 12-15). The assumption underlying charms is that the incantations (whether words or symbols or phonetic patterns) of a charm can effect a change in the state of the person or persons or inanimate object (a salve, for example, or a field for crops). -

'Goblinlike, Fantastic: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40443/ Version: Full Version Citation: Fergus, Emily (2019) ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email ‘Goblinlike, Fantastic’: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle Emily Fergus Submitted for MPhil Degree 2019 Birkbeck, University of London 2 I, Emily Fergus, confirm that all the work contained within this thesis is entirely my own. ___________________________________________________ 3 Abstract This thesis offers a new reading of how little people were presented in both fiction and non-fiction in the latter half of the nineteenth century. After the ‘discovery’ of African pygmies in the 1860s, little people became a powerful way of imaginatively connecting to an inconceivably distant past, and the place of humans within it. Little people in fin de siècle narratives have been commonly interpreted as atavistic, stunted warnings of biological reversion. I suggest that there are other readings available: by deploying two nineteenth-century anthropological theories – E. B. Tylor’s doctrine of ‘survivals’, and euhemerism, a model proposing that the mythology surrounding fairies was based on the existence of real ‘little people’ – they can also be read as positive symbols of the tenacity of the human spirit, and as offering access to a sacred, spiritual, or magic, world. -

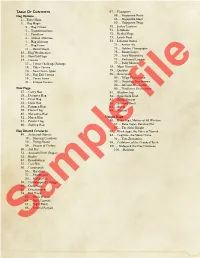

Table of Contents 67

Table Of Contents 67 . Hagspawn Hag Options 68 . Hagspawn Brute 2 . Elder Hags 68 . Hagspawn Mage 3 . Hag Magic 69 . Hagspawn Thug 3 . Hag Curses 70 . Jack o' Lantern 4 . Transformations 71 . Jermlaine 4 . Familiars 72 . Kenku Mage 4 . Animal Affinities 73 . Leech Toad 4 . Hag Alchemy 74 . Libation Oozes 7 . Hag Items 74 . Amber Ale 11 . Weird Magic 75 . Golden Champagne 15 . Hag Weaknesses 75 . Ebony Lager 16 . Non-Evil Hags 75 . Ivory Moonshine 17 . Covens 77 . Perfumed Liqueur 17 . Coven Challenge Ratings 77 . Ruby Merlot 18 . Elder Covens 78 . Moor Hound 18 . New Coven Types 79 . Quablyn 19 . Non-Evil Covens 80 . Scarecrow 19 . Coven Items 80 . Effigy Scarecrows 21 . Unique Covens 80 . Guardian Scarecrows 80 . Infernal Scarecrow New Hags 80 . Pestilence Scarecrows 27 . Carey Hag 81 . Shadow Asp 29 . Deemves Hag 82 . Sporeback Toad 31 . Deep Hag 82 . Stirge Swarm 33 . Dusk Hag 83 . Stitched Devil 35 . Fanggen Hag 84 . Styrix 38 . Hocus Hag 85 . Wastrel 40 . Marzanna Hag 42 . Mojan Hag Unique Hags 44 . Powler Hag 86 . Baba Yaga, Mother of All Witches 46 . Sighing Hag 87 . Baba Yaga's Dancing Hut 87 . The Solar Knight Hag Related Creatures 90 . Black Agga, the Voice of Vaprak 49 . Animated Objects 93 . Cegilune, the Moon Crone 49 . Dancing Cauldron 96 . Yaya Zhelamiss 50 . Flying Spoon 98 . Ceithlenn, of the Crooked Teeth 50 . Swarm of Cutlery 101 . Malagard, the Hag Countess 50 . Ash Rat 106 . Kalabon 52 . Assassin Devil (Dogai) 53 . Boglin 54 . Broodswarm 55 . Cait Sith 56 . Canomorph 56 . Haraknin 57 . Shadurakul 58 . Yeshbavhan 59 . Catobleopas Harbinger 60 . -

Introduction to Beowulf the Action of Beowulf "Beowulf" Seamus Heaney

Introduction to Beowulf 3182 lines in length, Beowulf is the longest surviving Old English poem. It survives in a single manuscript, thought to date from the turn of the eleventh century, though the composition of the poem is usually placed in the eighth or early ninth centuries, perhaps in an Anglian region. The action is set in Scandinavia, and the poem is chiefly concerned with the Geats (inhabitants of Southern Sweden), Danes and Swedes. It falls into two main sections, lls. 1-2199, which describe young Beowulf's defeat of two monsters, Grendel and his mother, at the request of King Hrothgar, and lls. 2200-3182, in which an aged Beowulf, now king, defeats a fire-breathing dragon but is mortally wounded and dies. This coursepack includes three short excerpts from the poem: Beowulf's fight with Grendel (ll. 702b-897), the so-called 'Lament of the Last Survivor' (2247-2266), and the poet's description of Beowulf's funeral (3156-3182). The former consists of the approach of Grendel to Heorot, and his hand-to-hand combat with Beowulf. The second contains the elegaic reflections of a warrior whom the poet imagines to be the sole remnant of a great tribe that once held the treasure now guarded by the dragon which threatens Beowulf's people. The poet powerfully conveys his nostalgia for dead companions and sense that treasure without an owner is worthless. The account of Beowulf's funeral describes a pagan cremation and records the Geats' epitaph for their dead leader. The Action of Beowulf Beowulf opens with a description of the origin and history of the Scylding dynasty, tracing its descent down to Hrothgar, who builds Heorot, a great hall. -

Widsith Beowulf. Beowulf Beowulf

CHAPTER 1 OLD ENGLISH LITERATURE The Old English language or Anglo-Saxon is the earliest form of English. The period is a long one and it is generally considered that Old English was spoken from about A.D. 600 to about 1100. Many of the poems of the period are pagan, in particular Widsith and Beowulf. The greatest English poem, Beowulf is the first English epic. The author of Beowulf is anonymous. It is a story of a brave young man Beowulf in 3182 lines. In this epic poem, Beowulf sails to Denmark with a band of warriors to save the King of Denmark, Hrothgar. Beowulf saves Danish King Hrothgar from a terrible monster called Grendel. The mother of Grendel who sought vengeance for the death of her son was also killed by Beowulf. Beowulf was rewarded and became King. After a prosperous reign of some forty years, Beowulf slays a dragon but in the fight he himself receives a mortal wound and dies. The poem concludes with the funeral ceremonies in honour of the dead hero. Though the poem Beowulf is little interesting to contemporary readers, it is a very important poem in the Old English period because it gives an interesting picture of the life and practices of old days. The difficulty encountered in reading Old English Literature lies in the fact that the language is very different from that of today. There was no rhyme in Old English poems. Instead they used alliteration. Besides Beowulf, there are many other Old English poems. Widsith, Genesis A, Genesis B, Exodus, The Wanderer, The Seafarer, Wife’s Lament, Husband’s Message, Christ and Satan, Daniel, Andreas, Guthlac, The Dream of the Rood, The Battle of Maldon etc. -

Old Me All About Her Impressions of It

~ ~ - ~ ~ ~.~· · ,,... ~~~ ~ T '-() ~ Morris Matters Volume 31, Number 2 July 2012 Contents of Volume 31 , Number 2 Morris Matters? ............................................................................................................... 2 by Long Lankin Olympic Dance Marathon - a Morris Dancer's Story........................................................ 4 by Tom Clare Isle of Wight Morris ............................................................................................................ 7 by Ian Anderson The Nine Hours Wander................................................................................................. 9 by Jonathan Hooton May Day Mice - A Review.............................................................................................. 12 by George Frampton Ten Thousand Hours.................................................................................................. 13 The Rapperlympics (DERT)........................................................................................... 15 by Sue Swift Morris in the News - Nineteenth Century....................................................................... 16 CD review : The Traditional Morris Dance Album............................. 22 by Jerry West CD review: The Morris On Band .................................................................... .. 23 by Jerry West Key to the Teams on Cover ............................................................................... .. 24 This issue of Morris Matters could not avoid the Olympics - but -

The Beowulf Manuscript Free

FREE THE BEOWULF MANUSCRIPT PDF R. D. Fulk | 400 pages | 04 May 2011 | HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9780674052956 | English | Cambridge, Mass, United States The Beowulf Manuscript What we can do is pay attention to top scholars in The Beowulf Manuscript field and make some pretty good guesses. Rather than being composed at a specific time, the poem probably developed out of various influences, especially folk tales and traditions. Parts of it may have originally been performed by court poets or The Beowulf Manuscript bards scops, pronounced "shops," in the Anglo-Saxon who would have sung or chanted their poems to the accompaniment of a The Beowulf Manuscript instrument such as a The Beowulf Manuscript. We can conclude, then, that the work grew out of popular art forms, that various influences worked together, and that the The Beowulf Manuscript may have changed as it developed. During the late s and early s, an American scholar named Milman Parry revolutionized the The Beowulf Manuscript of live performances of epics. He demonstrated convincingly that ancient Greek poems the Iliad and the Odyssey were composed in an oral-formulaic style based on tradition and designed to help the performer produce a long piece from memory or improvise material as he went along. Francis P. Magoun, Jr. XXVIII,demonstrates that the poems were recited The Beowulf Manuscript, more likely, sung or chanted, to audiences in the way that similar works are presented in Beowulf. An example The Beowulf Manuscript the epic itself is the performance of The Finnsburh Episode lines ff. Magoun points out that the bards relied on language specifically developed for the poetry, formulas worked out over a long period The Beowulf Manuscript time and designed to fit the The Beowulf Manuscript demands of a given line while expressing whatever ideas the poet wished to communicate. -

Violence, Christianity, and the Anglo-Saxon Charms Laurajan G

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1-1-2011 Violence, Christianity, And The Anglo-Saxon Charms Laurajan G. Gallardo Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Gallardo, Laurajan G., "Violence, Christianity, And The Anglo-Saxon Charms" (2011). Masters Theses. 293. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/293 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. *****US Copyright Notice***** No further reproduction or distribution of this copy is permitted by electronic transmission or any other means. The user should review the copyright notice on the following scanned image(s) contained in the original work from which this electronic copy was made. Section 108: United States Copyright Law The copyright law of the United States [Title 17, United States Code] governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that use may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Notre Dame Scholastic, Vol. 102, No. 11

a c/> c/> The most famous names in American men's wear are here for you: Eagle, Society Brand, GGG, Hickey-Freeman, Burberry, Alligator, 'Botany' 500, Alpagora, Arrow, Hathaway, Swank, McGregor, Bemhard Altmann, Dobbs, Florsheim . and many, many more. Truly the finest men's clothing and furnishings ob tainable in today's world markets. On the Cmnfius—Notre Drnne o &&& ... so select what you need now: a new suit or topcoat for the holidays ahead . gifts for special friends, and charge them the Campus Shop way. By the way, the Campus Shop will give you quick, expert fitting service so that what you purchase now will be altered and ready before. you leave the campus for the holidays. Merry Christmas and Happy New Year! CHARGE IT THE CAMPUS SHOP WAY 1/3 1/3 IN JUNE IN JULY No Carrying Charge ^ILBERrS On the Campus—Notre Dune Kttfa QaCampis MsShoIman (Author of "I Was a Teen-age Dwarf", "The Manii Loves of Dobie Gillis", etc.) DECK THE HALLS The time has come to make out our Robespierre, alas, was murdered quicker Inarticulate Society Christmas shopping lists, for Christmas than 3'ou could shout Jacques Robes Editor: %\-iU be upon us quicker than you can saj' pierre (or Jack Robinson as he is called Mr. Hudson, in last w^eek's Reper cussions, took issue with Mr. Smith's Jack Robinson. (Have j'ou ever won in the English-speaking countries). hierarchical theory of government: it dered, incidentall}--, about the origin of (There is, I am pleased to report, one was Mr.