William of Auvergne and Popular Demonology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clones Stick Together

TVhome The Daily Home April 12 - 18, 2015 Clones Stick Together Sarah (Tatiana Maslany) is on a mission to find the 000208858R1 truth about the clones on season three of “Orphan Black,” premiering Saturday at 8 p.m. on BBC America. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., April 12, 2015 — Sat., April 18, 2015 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING Friday WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 6 p.m. FS1 St. John’s Red Storm at Drag Racing WCIQ 7 10 4 Creighton Blue Jays (Live) WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Saturday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 7 p.m. ESPN2 Summitracing.com 12 p.m. ESPN2 Vanderbilt Com- WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 NHRA Nationals from The Strip at modores at South Carolina WEAC 24 24 Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Las Gamecocks (Live) WJSU 40 4 4 40 Vegas (Taped) 2 p.m. -

Pop Culture, Including at the Stateof Race in of Catch-Up? Gqlooks Just Playing Aslow Game Narrowing, Or Are We Racial Gapinhollywood Lena Dunham

THE > Pop Culture: Now in Living Color #oscarssowhite. Whitewashing. Lena Dunham. Is the racial gap in Hollywood narrowing, or are we just playing a slow game of catch-up? GQ looks at the state of race in pop culture, including JORDAN PEELE’S new racially tense horror movie, the not-so-woke trend of actors playing other ethnicities, and just how funny (or scary) it is to make fun of white people STYLIST: MICHAEL NASH. PROP STYLIST: FAETHGRUPPE. GROOMING: HEE SOO SOO HEE GROOMING: FAETHGRUPPE. STYLIST: PROP NASH. MICHAEL STYLIST: KLEIN. CALVIN TIE: AND SHIRT, SUIT, GOETZ. + MALIN FOR KWON PETER YANG MARCH 2017 GQ. COM 81 THEPUNCHLIST Jordan Peele Is Terrifying The Key & Peele star goes solo with a real horror story: being black in America jordan peele’s directorial debut, Get Out, is the story of a black man who visits the family of his white girlfriend and begins to suspect they’re either a little racist or plotting to annihilate him. Peele examined race for laughs on the Emmy-winning series Key & Peele. But Get Out expresses racial tension in a way we’ve never seen before: as the monster in a horror Why do you think that is? the layer of race that enriches flick. caity weaver EGG ON YOUR talked to Peele in his Black creators have not been and complicates that tension given a platform, and the [in Get Out] becomes relatable. (BLACK)FACE editing studio about African-American experience An index of racially using race as fodder for can only be dealt with by My dad is a black guy from questionable role-playing a popcorn thriller and an African-American. -

Theories of Truth. Bibliography on Primary Medieval Authors

Theories of Truth. Bibliography on Primary Medieval Authors https://www.ontology.co/biblio/truth-medieval-authors.htm Theory and History of Ontology by Raul Corazzon | e-mail: [email protected] History of Truth. Selected Bibliography on Medieval Primary Authors The Authors to which I will devote an entire page are marked with an asterisk (*). Hilary of Poitiers Augustine of Hippo (*) Boethius (*) Isidore of Seville John Scottus Eriugena (*) Isaac Israeli Avicenna (*) Anselm of Canterbury (*) Peter Abelard (*) Philip the Chancellor Robert Grosseteste William of Auvergne Albert the Great Bonaventure Thomas Aquinas (*) Henry of Ghent Siger of Brabant John Duns Scotus (*) Hervaeus Natalis Giles of Rome Durandus of St. Pourçain Peter Auriol Walter Burley William of Ockham (*) Robert Holkot John Buridan (*) 1 di 14 22/09/2016 09:25 Theories of Truth. Bibliography on Primary Medieval Authors https://www.ontology.co/biblio/truth-medieval-authors.htm Gregory of Rimini William of Heytesbury Peter of Mantua Paul of Venice Hilary of Poitiers (ca. 300 - 368) Texts 1. Meijering, E.P. 1982. Hilary of Poitiers on the Trinity. De Trinitate 1, 1-19, 2, 3. Leiden: Brill. In close cooperation with J. C. M: van Winden. On truth see I, 1-14. Studies Augustine of Hippo ( 354 - 430) Texts Studies 1. Boyer, Charles. 1921. L'idée De Vérité Dans La Philosophie De Saint Augustin. Paris: Gabriel Beauchesne. 2. Kuntz, Paul G. 1982. "St. Augustine's Quest for Truth: The Adequacy of a Christian Philosophy." Augustinian Studies no. 13:1-21. 3. Vilalobos, José. 1982. Ser Y Verdad En Agustín De Hipona. Sevilla: Publicaciones de la Universidad de Sevilla. -

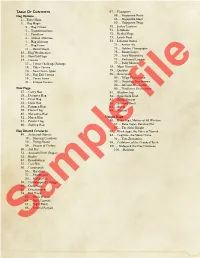

Table of Contents 67

Table Of Contents 67 . Hagspawn Hag Options 68 . Hagspawn Brute 2 . Elder Hags 68 . Hagspawn Mage 3 . Hag Magic 69 . Hagspawn Thug 3 . Hag Curses 70 . Jack o' Lantern 4 . Transformations 71 . Jermlaine 4 . Familiars 72 . Kenku Mage 4 . Animal Affinities 73 . Leech Toad 4 . Hag Alchemy 74 . Libation Oozes 7 . Hag Items 74 . Amber Ale 11 . Weird Magic 75 . Golden Champagne 15 . Hag Weaknesses 75 . Ebony Lager 16 . Non-Evil Hags 75 . Ivory Moonshine 17 . Covens 77 . Perfumed Liqueur 17 . Coven Challenge Ratings 77 . Ruby Merlot 18 . Elder Covens 78 . Moor Hound 18 . New Coven Types 79 . Quablyn 19 . Non-Evil Covens 80 . Scarecrow 19 . Coven Items 80 . Effigy Scarecrows 21 . Unique Covens 80 . Guardian Scarecrows 80 . Infernal Scarecrow New Hags 80 . Pestilence Scarecrows 27 . Carey Hag 81 . Shadow Asp 29 . Deemves Hag 82 . Sporeback Toad 31 . Deep Hag 82 . Stirge Swarm 33 . Dusk Hag 83 . Stitched Devil 35 . Fanggen Hag 84 . Styrix 38 . Hocus Hag 85 . Wastrel 40 . Marzanna Hag 42 . Mojan Hag Unique Hags 44 . Powler Hag 86 . Baba Yaga, Mother of All Witches 46 . Sighing Hag 87 . Baba Yaga's Dancing Hut 87 . The Solar Knight Hag Related Creatures 90 . Black Agga, the Voice of Vaprak 49 . Animated Objects 93 . Cegilune, the Moon Crone 49 . Dancing Cauldron 96 . Yaya Zhelamiss 50 . Flying Spoon 98 . Ceithlenn, of the Crooked Teeth 50 . Swarm of Cutlery 101 . Malagard, the Hag Countess 50 . Ash Rat 106 . Kalabon 52 . Assassin Devil (Dogai) 53 . Boglin 54 . Broodswarm 55 . Cait Sith 56 . Canomorph 56 . Haraknin 57 . Shadurakul 58 . Yeshbavhan 59 . Catobleopas Harbinger 60 . -

The Synagogue of Satan

THE SYNAGOGUE OF SATAN BY MAXIMILIAN J. RUDWIN THE Synagogue of Satan is of greater antiquity and potency than the Church of God. The fear of a mahgn being was earher in operation and more powerful in its appeal among primitive peoples than the love of a benign being. Fear, it should be re- membered, was the first incentive of religious worship. Propitiation of harmful powers was the first phase of all sacrificial rites. This is perhaps the meaning of the old Gnostic tradition that when Solomon was summoned from his tomb and asked, "Who first named the name of God?" he answered, "The Devil." Furthermore, every religion that preceded Christianity was a form of devil-worship in the eyes of the new faith. The early Christians actually believed that all pagans were devil-worshippers inasmuch as all pagan gods were in Christian eyes disguised demons who caused themselves to be adored under different names in dif- ferent countries. It was believed that the spirits of hell took the form of idols, working through them, as St. Thomas Aquinas said, certain marvels w'hich excited the wonder and admiration of their worshippers (Siiinina theologica n.ii.94). This viewpoint was not confined to the Christians. It has ever been a custom among men to send to the Devil all who do not belong to their own particular caste, class or cult. Each nation or religion has always claimed the Deity for itself and assigned the Devil to other nations and religions. Zoroaster described alien M^orshippers as children of the Divas, which, in biblical parlance, is equivalent to sons of Belial. -

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Magicians, Sorcerers and Witches: Considering Pretantric, Non-Sectarian Sources of Tantric Practices

Article Magicians, Sorcerers and Witches: Considering Pretantric, Non-sectarian Sources of Tantric Practices Ronald M. Davidson Department of Religious Studies, Farifield University, Fairfield, CT 06824, USA; [email protected] Received: 27 June 2017; Accepted: 23 August 2017; Published: 13 September 2017 Abstract: Most models on the origins of tantrism have been either inattentive to or dismissive of non-literate, non-sectarian ritual systems. Groups of magicians, sorcerers or witches operated in India since before the advent of tantrism and continued to perform ritual, entertainment and curative functions down to the present. There is no evidence that they were tantric in any significant way, and it is not clear that they were concerned with any of the liberation ideologies that are a hallmark of the sectarian systems, even while they had their own separate identities and specific divinities. This paper provides evidence for the durability of these systems and their continuation as sources for some of the ritual and nomenclature of the sectarian tantric traditions, including the predisposition to ritual creativity and bricolage. Keywords: tantra; mantra; ritual; magician; sorcerer; seeress; vidyādhara; māyākāra; aindrajālika; non-literate 1. Introduction1 In the emergence of alternative religious systems such as tantrism, a number of factors have historically been seen at play. Among these are elements that might be called ‘pre-existing’. That is, they themselves are not representative of the eventual emergent system, but they provide some of the raw material—ritual, ideological, terminological, functional, or other—for its development. Indology, and in particular the study of Indian ritual, has been less than adroit at discussing such phenomena, especially when it may be designated or classified as ‘magical’ in some sense. -

SOURCES of MEDIEVAL DEMONOLOGY by Diana Lynn Walzel When Most of Us Think of Demons Today, If We Do Think of Them, Some Medieval Imp Undoubtedly Comes to Mind

SOURCES OF MEDIEVAL DEMONOLOGY by Diana Lynn Walzel When most of us think of demons today, if we do think of them, some medieval imp undoubtedly comes to mind. The lineage of the medieval demon, and the modern conception thereof, can be traced to four main sources, all of which have links to the earliest human civilizations. Greek philosophy, Jewish apocryphal literature, Biblical doctrine, and pagan Germanic folklore all contribute elements to the demons which flourished in men's minds at the close of the medieval period. It is my purpose briefly to delineate the demonology of each of these sources and to indicate their relationship to each other. Homer had equated demons with gods and used daimon and theos as synonyms. Later writers gave a different nuance and even definition to the word daimon, but the close relationship between demons and the gods was never completely lost from sight. In the thinkers of Middle Platonism the identification of demons with the gods was revived, and this equation is ever-present in Christian authors. Hesiod had been the first to view demons as other than gods, consider- ing them the departed souls of men living in the golden age. Going a step further, Pythagoras believed the soul of any man became a demon when separated from the body. A demon, then, was simply a bodiless soul. In Platonic thought there was great confusion between demons and human souls. There seems to have been an actual distinction between the two for Plato, but what the distinction was is impossible now to discern. -

Notre Dame Scholastic, Vol. 102, No. 11

a c/> c/> The most famous names in American men's wear are here for you: Eagle, Society Brand, GGG, Hickey-Freeman, Burberry, Alligator, 'Botany' 500, Alpagora, Arrow, Hathaway, Swank, McGregor, Bemhard Altmann, Dobbs, Florsheim . and many, many more. Truly the finest men's clothing and furnishings ob tainable in today's world markets. On the Cmnfius—Notre Drnne o &&& ... so select what you need now: a new suit or topcoat for the holidays ahead . gifts for special friends, and charge them the Campus Shop way. By the way, the Campus Shop will give you quick, expert fitting service so that what you purchase now will be altered and ready before. you leave the campus for the holidays. Merry Christmas and Happy New Year! CHARGE IT THE CAMPUS SHOP WAY 1/3 1/3 IN JUNE IN JULY No Carrying Charge ^ILBERrS On the Campus—Notre Dune Kttfa QaCampis MsShoIman (Author of "I Was a Teen-age Dwarf", "The Manii Loves of Dobie Gillis", etc.) DECK THE HALLS The time has come to make out our Robespierre, alas, was murdered quicker Inarticulate Society Christmas shopping lists, for Christmas than 3'ou could shout Jacques Robes Editor: %\-iU be upon us quicker than you can saj' pierre (or Jack Robinson as he is called Mr. Hudson, in last w^eek's Reper cussions, took issue with Mr. Smith's Jack Robinson. (Have j'ou ever won in the English-speaking countries). hierarchical theory of government: it dered, incidentall}--, about the origin of (There is, I am pleased to report, one was Mr. -

Page 210 H-France Review Vol. 8 (March 2008), No. 52 Roland J

H-France Review Volume 8 (2008) Page 210 H-France Review Vol. 8 (March 2008), No. 52 Roland J. Teske, Studies in the Philosophy of William of Auvergne, Bishop of Paris (1228-1249). Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2006. 274 pp. Table, introduction, notes, bibliography, and indexes. $30.00 U.S. (pb). ISBN 0-87462-674-9. Review by Steven P. Marrone, Tufts University. William of Auvergne, master of theology at the University of Paris and bishop of that city from 1228 until his death in 1249, was one of the most prominent Latin theologians of his day, recognized for his intellectual import throughout much of the rest of the thirteenth century. Yet the modern historiography of scholastic thought has paid him relatively little attention. The only book devoted to the entirety of his thinking, a three-volume study by Amato Masnovo, appeared well over half a century ago.[1] With the new work under review here, gathering together thirteen essays on aspects of William’s philosophy originally published between 1990 and 2003, Roland Teske goes a long way towards redressing the balance. In the name of full disclosure, I should admit that as an author of two books in which William’s speculative achievements play a major role, I cannot be considered an impartial witness to Teske’s effort.[2] All the same, I believe that anyone who reads Teske’s book will come away convinced that William deserves just the sort of probing and sustained examination Teske has given him. For the sake of our accurate appreciation of the historical trajectory of thirteenth-century scholasticism, I hope the book has many readers. -

De-Demonising the Old Testament

De-Demonising the Old Testament An Investigation of Azazel , Lilith , Deber , Qeteb and Reshef in the Hebrew Bible Judit M. Blair Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh 2008 Declaration I declare that the present thesis has been composed by me, that it represents my own research, and that it has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. ______________________ Judit M. Blair ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people to thank and acknowledge for their support and help over the past years. Firstly I would like to thank the School of Divinity for the scholarship and the opportunity they provided me in being able to do this PhD. I would like to thank my ‘numerous’ supervisors who have given of their time, energy and knowledge in making this thesis possible: To Professor Hans Barstad for his patience, advice and guiding hand, in particular for his ‘adopting’ me as his own. For his understanding and help with German I am most grateful. To Dr Peter Hayman for giving of his own time to help me in learning Hebrew, then accepting me to study for a PhD, and in particular for his attention to detail. To Professor Nick Wyatt who supervised my Masters and PhD before his retirement for his advice and support. I would also like to thank the staff at New College Library for their assistance at all times, and Dr Jessie Paterson and Bronwen Currie for computer support. My fellow colleagues have provided feedback and helpful criticism and I would especially like to thank all members of HOTS-lite I have known over the years. -

Berserkir: a Double Legend

Brathair 4 (2), 2004: 97-101 ISSN 1519-9053 Berserkir: A Double Legend Prof. Dr. Anatoly Liberman University of Minnesota (USA) [email protected] Resumo O artigo analisa o tema dos guerreiros da Escandinávia Viking conhecidos como Berserkir, concluindo que as tradicionais associações com o deus Óðinn, formação de grupos secretos e a utilização de alucinógenos foram produtos da fantasia dos escritores cristãos, sem nenhuma base histórica. Palavras-chave: Mitologia, sociedade Viking, literatura medieval Resumé Le travaille analyse le thème des guerriers de l’Escandinavie Viking ont connu comme Berserkir, que conclut que les traditionels associations avec le dieu Odin, formations de groupes sécrets et l’utilization des hallucinogènes allaient produits de la fantasie des ècrivans chrètienes sans aucun base historique. Mots-clé: Mythologie, société Viking, littérature medievale http://www.brathair.cjb.net 97 Brathair 4 (2), 2004: 97-101 ISSN 1519-9053 It sometimes happens that modern scholars know something about antiquity and the Middle Ages hidden from those who lived at that time. For example, unlike Plato, we can etymologize many Ancient Greek words. Perhaps we even understand a few lines of skaldic poetry better than did Snorri. But berserkir (whom, to simplify matters, I will call berserkers, as is done in English dictionaries) fared badly. The Vikings’ contemporaries had lost all memory of berserkers’ identity. In the 13th century, berserkers reemerged in the sagas as society’s dangerous outcasts and soon disappeared without a trace until medievalists revived them in their works. The berserker-related boom is now behind us, but an impressive bibliography of the subject testifies to scholarship devoid of a factual base and feeding mainly on itself.