Structure of Protistan Parasites Found in Bivalve Molluscs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

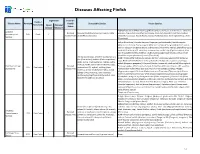

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE MACRONUTRIENTS SHAPE MICROBIAL COMMUNITIES, GENE EXPRESSION AND PROTEIN EVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By JOSHUA THOMAS COOPER Norman, Oklahoma 2017 MACRONUTRIENTS SHAPE MICROBIAL COMMUNITIES, GENE EXPRESSION AND PROTEIN EVOLUTION A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF MICROBIOLOGY AND PLANT BIOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Boris Wawrik, Chair ______________________________ Dr. J. Phil Gibson ______________________________ Dr. Anne K. Dunn ______________________________ Dr. John Paul Masly ______________________________ Dr. K. David Hambright ii © Copyright by JOSHUA THOMAS COOPER 2017 All Rights Reserved. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my two advisors Dr. Boris Wawrik and Dr. J. Phil Gibson for helping me become a better scientist and better educator. I would also like to thank my committee members Dr. Anne K. Dunn, Dr. K. David Hambright, and Dr. J.P. Masly for providing valuable inputs that lead me to carefully consider my research questions. I would also like to thank Dr. J.P. Masly for the opportunity to coauthor a book chapter on the speciation of diatoms. It is still such a privilege that you believed in me and my crazy diatom ideas to form a concise chapter in addition to learn your style of writing has been a benefit to my professional development. I’m also thankful for my first undergraduate research mentor, Dr. Miriam Steinitz-Kannan, now retired from Northern Kentucky University, who was the first to show the amazing wonders of pond scum. Who knew that studying diatoms and algae as an undergraduate would lead me all the way to a Ph.D. -

Pathogens Table 2006

Important pathogens and parasites of molluscs Genetic and Pathology Laboratory Pathogen or parasite Host species Host impact Geographical distribution Infection period Diagnostic Cycle Species Group Denmark, Netherland, Incubation period : 3-4 month Ostrea edulis, O. Parasite of oyster haemocytes Throughout the year France, Ireland, Great Britain in infected area. Histology, Bonamia ostreae Protozoan Conchaphila, O. Angasi, O. (=>all the tissues can be invaded). (with a peak in Direct (except Scotland), Italy, tissue imprint, PCR, ISH, Puelchana, Tiostrea chilensis Oyster mortality September) Spain and USA electron microscopy Parasite of oyster haemocytes Throughout the year Histology, tissue imprint, Ostrea angasi, Ostrea Australia, New Zéland, Bonamia exitiosa Protozoan (=>all the tissues can be invaded). (with a peak during PCR, ISH, electron Unknown chilensis, Ostrea edulis Tasmania, Spain (in 2007) Oyster mortality Australian autumn) microscopy Parasites present in connective Histology, tissue imprint, Haplosporidium tissue (mantle, gonads, digestive Protozoan Crassostrea virginica USA, Canada Spring-summer PCR, ISH, electron Unknown costale gland) but not in digestive tubule microscopy epithelia. Mortality in May-June Parasites present in gills, connective tissue. Sporulation only Histology, tissue imprint, Unknown but Haplosporidium Crassostrea virginica, USA, Canada, Japan, Korea, Summer (May until Protozoan in the epithelium of digestive gland smear, PCR, HIS, electron intermediate host is nelsoni Crassostrea gigas France October) in C. virginica, Mortalities in C. microscopy suspected virginica. No mortality in C. gigas Parasite present in connective Haplosporidium Protozoan O. edulis, O. angasi tissue. Sometimes, mortality can France, Netherland, Spain Histology, tissue imprint Unknown armoricanum be observed Ostrea edulis , Tiostrea Spring-summer Histology, tissue imprint, ISH, Intermediate host: Extracellular parasite of the Marteilia refringens Protozoan chilensis, O. -

Symbiodinium Genomes Reveal Adaptive Evolution of Functions Related to Symbiosis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/198762; this version posted October 5, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Article 2 Symbiodinium genomes reveal adaptive evolution of 3 functions related to symbiosis 4 Huanle Liu1, Timothy G. Stephens1, Raúl A. González-Pech1, Victor H. Beltran2, Bruno 5 Lapeyre3,4, Pim Bongaerts5, Ira Cooke3, David G. Bourne2,6, Sylvain Forêt7,*, David J. 6 Miller3, Madeleine J. H. van Oppen2,8, Christian R. Voolstra9, Mark A. Ragan1 and Cheong 7 Xin Chan1,10,† 8 1Institute for Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072, 9 Australia 10 2Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, QLD 4810, Australia 11 3ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies and Department of Molecular and Cell 12 Biology, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD 4811, Australia 13 4Laboratoire d’excellence CORAIL, Centre de Recherches Insulaires et Observatoire de 14 l’Environnement, Moorea 98729, French Polynesia 15 5Global Change Institute, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia 16 6College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD 4811, 17 Australia 18 7Research School of Biology, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia 19 8School of BioSciences, The University of Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/198762; this version posted October 5, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

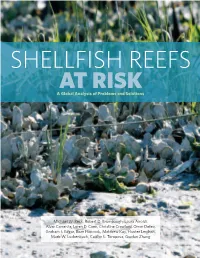

Shellfish Reefs at Risk

SHELLFISH REEFS AT RISK A Global Analysis of Problems and Solutions Michael W. Beck, Robert D. Brumbaugh, Laura Airoldi, Alvar Carranza, Loren D. Coen, Christine Crawford, Omar Defeo, Graham J. Edgar, Boze Hancock, Matthew Kay, Hunter Lenihan, Mark W. Luckenbach, Caitlyn L. Toropova, Guofan Zhang CONTENTS Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Methods .................................................................................................................................... 10 Results ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Condition of Oyster Reefs Globally Across Bays and Ecoregions ............ 14 Regional Summaries of the Condition of Shellfish Reefs ............................ 15 Overview of Threats and Causes of Decline ................................................................ 28 Recommendations for Conservation, Restoration and Management ................ 30 Conclusions ............................................................................................................................ 36 References ............................................................................................................................. -

Drawing the Tree of Eukaryotic Life Based on the Analysis of 2,269 Comment Manually Annotated Myosins from 328 Species Florian Odronitz and Martin Kollmar

Open Access Research2007OdronitzVolume 8, and Issue Kollmar 9, Article R196 Drawing the tree of eukaryotic life based on the analysis of 2,269 comment manually annotated myosins from 328 species Florian Odronitz and Martin Kollmar Address: Department of NMR-based Structural Biology, Max-Planck-Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Am Fassberg, 37077 Goettingen, Germany. Correspondence: Martin Kollmar. Email: [email protected] reviews Published: 18 September 2007 Received: 6 March 2007 Revised: 17 September 2007 Genome Biology 2007, 8:R196 (doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r196) Accepted: 18 September 2007 The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found online at http://genomebiology.com/2007/8/9/R196 © 2007 Odronitz and Kollmar; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which reports permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The<p>Thesome eukaryotic accepted tree of relationshipstreeeukaryotic of life life of was major reconstr taxa anducted resolving based on disputed the analysis and preliminary of 2,269 myosin classifications.</p> motor domains from 328 organisms, confirming Abstract deposited research Background: The evolutionary history of organisms is expressed in phylogenetic trees. The most widely used phylogenetic trees describing the evolution of all organisms have been constructed based on single-gene phylogenies that, however, often produce conflicting results. Incongruence between phylogenetic trees can result from the violation of the orthology assumption and stochastic and systematic errors. Results: Here, we have reconstructed the tree of eukaryotic life based on the analysis of 2,269 myosin motor domains from 328 organisms. -

Olympia Oyster (Ostrea Lurida)

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea lurida in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2011 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2011. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea lurida in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xi + 56 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2000. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea conchaphila in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 30 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Gillespie, G.E. 2000. COSEWIC status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea conchaphila in Canada in COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea conchaphila in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-30 pp. Production note: COSEWIC acknowledges Graham E. Gillespie for writing the provisional status report on the Olympia Oyster, Ostrea lurida, prepared under contract with Environment Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada. The contractor’s involvement with the writing of the status report ended with the acceptance of the provisional report. Any modifications to the status report during the subsequent preparation of the 6-month interim and 2-month interim status reports were overseen by Robert Forsyth and Dr. Gerald Mackie, COSEWIC Molluscs Specialist Subcommittee Co-Chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’huître plate du Pacifique (Ostrea lurida) au Canada. -

Symbiodinium Genomes Reveal Adaptive Evolution of Functions Related to Coral-Dinoflagellate Symbiosis

Corrected: Publisher correction ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s42003-018-0098-3 OPEN Symbiodinium genomes reveal adaptive evolution of functions related to coral-dinoflagellate symbiosis Huanle Liu1, Timothy G. Stephens1, Raúl A. González-Pech1, Victor H. Beltran2, Bruno Lapeyre3,4,12, Pim Bongaerts5,6, Ira Cooke4, Manuel Aranda7, David G. Bourne2,8, Sylvain Forêt3,9, David J. Miller3,4, Madeleine J.H. van Oppen2,10, Christian R. Voolstra7, Mark A. Ragan1 & Cheong Xin Chan1,11 1234567890():,; Symbiosis between dinoflagellates of the genus Symbiodinium and reef-building corals forms the trophic foundation of the world’s coral reef ecosystems. Here we present the first draft genome of Symbiodinium goreaui (Clade C, type C1: 1.03 Gbp), one of the most ubiquitous endosymbionts associated with corals, and an improved draft genome of Symbiodinium kawagutii (Clade F, strain CS-156: 1.05 Gbp) to further elucidate genomic signatures of this symbiosis. Comparative analysis of four available Symbiodinium genomes against other dinoflagellate genomes led to the identification of 2460 nuclear gene families (containing 5% of Symbiodinium genes) that show evidence of positive selection, including genes involved in photosynthesis, transmembrane ion transport, synthesis and modification of amino acids and glycoproteins, and stress response. Further, we identify extensive sets of genes for meiosis and response to light stress. These draft genomes provide a foundational resource for advancing our understanding of Symbiodinium biology and the coral-algal symbiosis. 1 Institute for Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia. 2 Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, QLD 4810, Australia. 3 ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD 4811, Australia. -

Prevalent Ciliate Symbiosis on Copepods: High Genetic Diversity and Wide Distribution Detected Using Small Subunit Ribosomal RNA Gene

Prevalent Ciliate Symbiosis on Copepods: High Genetic Diversity and Wide Distribution Detected Using Small Subunit Ribosomal RNA Gene Zhiling Guo1,2, Sheng Liu1, Simin Hu1, Tao Li1, Yousong Huang4, Guangxing Liu4, Huan Zhang2,4*, Senjie Lin2,3* 1 Key Laboratory of Marine Bio-resources Sustainable Utilization, South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Science, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, 2 Department of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut, Groton, Connecticut, United States of America, 3 Marine Biodiversity and Global Change Laboratory, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, China, 4 Department of Environmental Science, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, Shandong, China Abstract Toward understanding the genetic diversity and distribution of copepod-associated symbiotic ciliates and the evolutionary relationships with their hosts in the marine environment, we developed a small subunit ribosomal RNA gene (18S rDNA)- based molecular method and investigated the genetic diversity and genotype distribution of the symbiotic ciliates on copepods. Of the 10 copepod species representing six families collected from six locations of Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, 9 were found to harbor ciliate symbionts. Phylogenetic analysis of the 391 ciliate 18S rDNA sequences obtained revealed seven groups (ribogroups), six (containing 99% of all the sequences) belonging to subclass Apostomatida, the other clustered with peritrich ciliate Vorticella gracilis. Among the Apostomatida groups, Group III were essentially identical to Vampyrophrya pelagica, and the other five groups represented the undocumented ciliates that were close to Vampyrophrya/ Gymnodinioides/Hyalophysa. Group VI ciliates were found in all copepod species but one (Calanus sinicus), and were most abundant among all ciliate sequences obtained, indicating that they are the dominant symbiotic ciliates universally associated with copepods. -

Assessment of the Cell Viability of Cultured Perkinsus Marinus

J. Eukaryot. Microbiol., 52(6), 2005 pp. 492–499 r 2005 by the International Society of Protistologists DOI: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00058.x Assessment of the Cell Viability of Cultured Perkinsus marinus (Perkinsea), a Parasitic Protozoan of the Eastern Oyster, Crassostrea virginica, Using SYBRgreen–Propidium Iodide Double Staining and Flow Cytometry PHILIPPE SOUDANT,a,1 FU-LIN E. CHUb and ERIC D. LUNDb aLEMAR, UMR 6539, IUEM-UBO, Technopole Brest-Iroise, Place Nicolas Copernic, 29280 Plouzane´, France, and bVirginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary, Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062, USA ABSTRACT. A flow cytometry (FCM) assay using SYBRgreen and propidium iodide double staining was tested to assess viability and morphological parameters of Perkinsus marinus under different cold- and heat-shock treatments and at different growth phases. P. mari- nus meront cells, cultivated at 28 1C, were incubated in triplicate for 30 min at À 80 1C, À 20 1C, 5 1C, and 20 1C for cold-shock treatments and at 32 1C, 36 1C, 40 1C, 44 1C, 48 1C, 52 1C, and 60 1C for heat-shock treatments. A slight and significant decrease in percentage of viable cells (PVC), from 93.6% to 92.7%, was observed at À 20 1C and the lowest PVC was obtained at À 80 1C (54.0%). After 30 min of heat shocks at 40 1C and 44 1C, PVC decreased slightly but significantly compared to cells maintained at 28 1C. When cells were heat shocked at 48 1C, 52 1C, and 60 1C heavy mortality occurred and PVC decreased to 33.8%, 8.0%, and 3.4%, respectively. -

Aquatic Microbial Ecology 79:1

Vol. 79: 1–12, 2017 AQUATIC MICROBIAL ECOLOGY Published online March 28 https://doi.org/10.3354/ame01811 Aquat Microb Ecol Contribution to AME Special 6 ‘SAME 14: progress and perspectives in aquatic microbial ecology’ OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS REVIEW Exploring the oceanic microeukaryotic interactome with metaomics approaches Anders K. Krabberød1, Marit F. M. Bjorbækmo1, Kamran Shalchian-Tabrizi1, Ramiro Logares2,1,* 1University of Oslo, Department of Biosciences, Section for Genetics and Evolutionary Biology (Evogene), Blindernv. 31, 0316 Oslo, Norway 2Institute of Marine Sciences (ICM), CSIC, Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta, Barcelona, Spain ABSTRACT: Biological communities are systems composed of many interacting parts (species, populations or single cells) that in combination constitute the functional basis of the biosphere. Animal and plant ecologists have advanced substantially our understanding of ecological inter- actions. In contrast, our knowledge of ecological interaction in microbes is still rudimentary. This represents a major knowledge gap, as microbes are key players in almost all ecosystems, particu- larly in the oceans. Several studies still pool together widely different marine microbes into broad functional categories (e.g. grazers) and therefore overlook fine-grained species/population-spe- cific interactions. Increasing our understanding of ecological interactions is particularly needed for oceanic microeukaryotes, which include a large diversity of poorly understood symbiotic rela- tionships that range from mutualistic to parasitic. The reason for the current state of affairs is that determining ecological interactions between microbes has proven to be highly challenging. How- ever, recent technological developments in genomics and transcriptomics (metaomics for short), coupled with microfluidics and high-performance computing are making it increasingly feasible to determine ecological interactions at the microscale. -

Is Pallial Mucus Involved in Ostrea Edulis Defenses Against the Parasite Bonamia

1 Is pallial mucus involved in Ostrea edulis defenses against the parasite Bonamia 2 ostreae? 3 Sergio Fernández-Boo1,4*, Ophélie Gervais1, Maria Prado-Alvarez3 Bruno Chollet1, 4 Stéphane Claverol2, Cyrielle Lecadet1, Christine Dubreuil1, Isabelle Arzul1 5 1 Institut Français de Recherche pour l´Exploitation de la Mer (IFREMER), Laboratoire de 6 Génétique et Pathologie (LGP), Avenue Mus de Loup, 17390 La Tremblade, France. 7 2 Université de Bordeaux, Centre Génomique Fonctionnelle de Bordeaux, Plateforme 8 Protéome, F-33000 Bordeaux, France. 9 3 Aquatic Molecular Pathobiology Group. Marine Research Institute (IIM-CSIC). Vigo. 10 Spain. 11 4 Centro Interdisciplinar de Investigação Marinha e Ambiental (CIIMAR), University of 12 Porto, Avenida General Norton de Matos, S/N, 4450-208 Matosinhos, Portugal. 13 14 *Corresponding author: [email protected] 15 Abstract 16 Bonamia ostreae is an intrahemocytic parasite that has been responsible for severe 17 mortalities in the flat oyster Ostrea edulis since the 1970´s. The Pacific oyster 18 Crassostrea gigas is considered to be resistant to the disease and appears to have 19 mechanisms to avoid infection. Most studies carried out on the invertebrate immune 20 system focus on the role of hemolymph, although mucus, which covers the body surface 21 of molluscs, could also act as a barrier against pathogens. In this study, the in vitro effect 22 of mucus from the oyster species Ostrea edulis and C. gigas on B. ostreae was 23 investigated using flow cytometry. Results showed an increase in esterase activities and 24 mortality rate of parasites exposed to mucus from both oyster species.