Chapter I Taxonomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

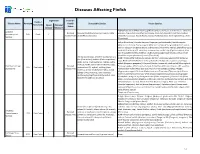

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

Paleontology and Sedimentology of Middle Eocene Rocks in Lago Argentino Area, Santa Cruz Province, Argentina

AMEGHINIANA (Rev. Asoc. Paleontol. Argent.) - 46 (1): 27-47. Buenos Aires, 30-04-2009 ISSN 0002-7014 Paleontology and sedimentology of Middle Eocene rocks in Lago Argentino area, Santa Cruz Province, Argentina Silvio CASADÍO1,2, Miguel GRIFFIN1,2, Sergio MARENSSI3,2, Laura NET4, Ana PARRAS1,2, Martín RODRÍGUEZ RAISING5,2 and Sergio SANTILLANA3 Abstract. Sedimentological and paleontological study of the Man Aike Formation at the Estancia 25 de Mayo, SW of Santa Cruz Province, Argentina, represents the evolution of an incised valley from fluvial to marine environment during the late middle Eocene. At the base of the unit there is an unconformity that corresponds to fluvial channels which cut down into the underlying Maastrichtian sandstones of the Calafate Formation. The fauna of invertebrates (mostly molluscs) illustrated herein was collected from shell beds interpreted as tidal ravinement surfaces. The fauna includes terebratulid brachiopods, bivalves of the families Malletiidae, Mytilidae, Pinnidae, Ostreidae, Pectinidae, Carditidae, Crassatellidae, Lahillidae, Mactridae, Veneridae, and Hiatellidae, and gastropods of the families Trochidae and Calyptraeidae, and a member of Archaeogastropoda of uncertain affinities. The similarities of this fauna with that recorded in the Upper Member of the Río Turbio Formation, together with 87Sr/86Sr ages, sug- gest a late Middle Eocene age for the Man Aike Formation. Resumen. PALEONTOLOGÍA Y SEDIMENTOLOGÍA DE LAS ROCAS DEL EOCENO MEDIO EXPUESTAS EN EL ÁREA DE LAGO ARGENTINO, PROVINCIA DE SANTA CRUZ, ARGENTINA. Los estudios sedimentológicos y paleontológicos real- izados en rocas asignadas a la Formación Man Aike, expuestas en la estancia 25 de Mayo, al sur de Calafate, provincia de Santa Cruz, Argentina, sugieren que esta unidad representa la evolución de un valle inciso desde ambientes fluviales a marinos durante el Eoceno medio tardío. -

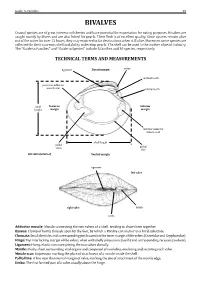

Field Identification Guide to the Living Marine Resources In

Guide to Families 29 BIVALVES Coastal species are of great interest to fisheries and have potential for exportation for eating purposes. Bivalves are caught mainly by divers and are also fished for pearls. Their flesh is of excellent quality. Since oysters remain alive out of the water for over 12 hours, they may exported to far destinations when still alive. Moreover, some species are collected for their nacreous shell and ability to develop pearls. The shell can be used in the mother of pearl industry. The “Guide to Families’’ andTECHNICAL ‘‘Guide to Species’’ TERMS include 5AND families MEASUREMENTS and 10 species, respectively. ligament Dorsal margin umbo posterior adductor cardinal tooth muscle scar lateral tooth Posterior Anterior margin margin shell height anterior adductor muscle scar pallial sinus pallial shell length line left valve (interior) Ventral margin ligament left valve right valve lunule umbo Adductor muscle: Byssus: Chomata: Muscle connecting the two valves of a shell, tending to draw them together. Hinge: Clump of horny threads spun by the foot, by which a Bivalve can anchor to a hard substrate. Ligament: Small denticles and corresponding pits located on the inner margin of the valves (Ostreidae and Gryphaeidae). Mantle: Top interlocking margin of the valves, often with shelly projections (teeth) and corresponding recesses (sockets). Muscle scar: Horny, elastic structure joining the two valves dorsally. Pallial line: Fleshy sheet surrounding vital organs and composed of two lobes, one lining and secreting each valve. Umbo: Impression marking the place of attachment of a muscle inside the shell. A line near the internal margin of valve, marking the site of attachment of the mantle edge. -

Pathogens Table 2006

Important pathogens and parasites of molluscs Genetic and Pathology Laboratory Pathogen or parasite Host species Host impact Geographical distribution Infection period Diagnostic Cycle Species Group Denmark, Netherland, Incubation period : 3-4 month Ostrea edulis, O. Parasite of oyster haemocytes Throughout the year France, Ireland, Great Britain in infected area. Histology, Bonamia ostreae Protozoan Conchaphila, O. Angasi, O. (=>all the tissues can be invaded). (with a peak in Direct (except Scotland), Italy, tissue imprint, PCR, ISH, Puelchana, Tiostrea chilensis Oyster mortality September) Spain and USA electron microscopy Parasite of oyster haemocytes Throughout the year Histology, tissue imprint, Ostrea angasi, Ostrea Australia, New Zéland, Bonamia exitiosa Protozoan (=>all the tissues can be invaded). (with a peak during PCR, ISH, electron Unknown chilensis, Ostrea edulis Tasmania, Spain (in 2007) Oyster mortality Australian autumn) microscopy Parasites present in connective Histology, tissue imprint, Haplosporidium tissue (mantle, gonads, digestive Protozoan Crassostrea virginica USA, Canada Spring-summer PCR, ISH, electron Unknown costale gland) but not in digestive tubule microscopy epithelia. Mortality in May-June Parasites present in gills, connective tissue. Sporulation only Histology, tissue imprint, Unknown but Haplosporidium Crassostrea virginica, USA, Canada, Japan, Korea, Summer (May until Protozoan in the epithelium of digestive gland smear, PCR, HIS, electron intermediate host is nelsoni Crassostrea gigas France October) in C. virginica, Mortalities in C. microscopy suspected virginica. No mortality in C. gigas Parasite present in connective Haplosporidium Protozoan O. edulis, O. angasi tissue. Sometimes, mortality can France, Netherland, Spain Histology, tissue imprint Unknown armoricanum be observed Ostrea edulis , Tiostrea Spring-summer Histology, tissue imprint, ISH, Intermediate host: Extracellular parasite of the Marteilia refringens Protozoan chilensis, O. -

Geological Survey

DEPABTMENT OF THE INTEKIOR BULLETIN OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY N~o. 151 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1898 UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIEECTOR THE LOWER CRETACEOUS GRYPMAS OF THK TEX.AS REGION ROBERT THOMAS HILL THOMAS WAYLA'ND VAUGHAN WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT FEINTING OFFICE 18.98 THE LOWER CRETACEOUS GRYPHJ1AS OF THE TEXAS REGION. BY I EOBEET THOMAS HILL and THOMAS WAYLAND VAUGHAN. CONTENTS. Page. Letter of transmittal....._..........._....._ ............................ 11 Introduction ...---._._....__................._....._.__............._...._ 13 The fossil oysters of the Texas region.._._.._.___._-..-._._......-..--.... 23 Classification of the Ostreidae. .. ...-...---..-.......-.....-.-............ 24 Historical statement of the discovery in the Texas region of the forms referred to Gryphsea pitcher! Morton ................................ 33 Gryphaea corrugata Say._______._._..__..__...__.,_._.________...____.._ 33 Gryphsea pitcheri Morton............................................... 34 Roemer's Gryphsea pitcheri............................................ 35 Marcou's Gryphsea pitcheri............................................ 35 Blake's Gryphaea pitcheri............................................. 36 Schiel's Gryphsea pitcheri...........................,.:................ 36 Hall's Gryphsea pitcheri (= G. dilatata var. tucumcarii Marcou) ...... 36 Heilprin's Gryphaea pitcheri.....'..................................... 37 Gryphaea pitcheri var. hilli Cragin................................... -

Breeding and Domestication of Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea

W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Articles Virginia Institute of Marine Science 2014 Breeding And Domestication Of Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea Virginica) Lines For Culture In The Mid-Atlantic, Usa: Line Development And Mass Selection For Disease Resistance Anu Frank-Lawale Virginia Institute of Marine Science Standish K. Allen Jr. Virginia Institute of Marine Science Lionel Degremont Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Frank-Lawale, Anu; Allen, Standish K. Jr.; and Degremont, Lionel, "Breeding And Domestication Of Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea Virginica) Lines For Culture In The Mid-Atlantic, Usa: Line Development And Mass Selection For Disease Resistance" (2014). VIMS Articles. 334. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles/334 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in VIMS Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 33, No. 1, 153–165, 2014. BREEDING AND DOMESTICATION OF EASTERN OYSTER (CRASSOSTREA VIRGINICA) LINES FOR CULTURE IN THE MID-ATLANTIC, USA: LINE DEVELOPMENT AND MASS SELECTION FOR DISEASE RESISTANCE ANU FRANK-LAWALE,* STANDISH K. ALLEN, JR. AND LIONEL DE´GREMONT† Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Aquaculture Genetics and Breeding Technology Center, College of William and Mary, 1375 Greate Road, Gloucester Point, VA 23062 ABSTRACT A selective breeding program for Crassostrea virginica was established in 1997 as part of an initiative in Virginia to address declining oyster harvests caused by the two oyster pathogens Haplosporidium nelsoni (MSX) and Perkinsus marinus (Dermo). -

Biogeographical Homogeneity in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. II

Vol. 19: 75–84, 2013 AQUATIC BIOLOGY Published online September 4 doi: 10.3354/ab00521 Aquat Biol Biogeographical homogeneity in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. II. Temporal variation in Lebanese bivalve biota Fabio Crocetta1,*, Ghazi Bitar2, Helmut Zibrowius3, Marco Oliverio4 1Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, Villa Comunale, 80121, Napoli, Italy 2Department of Natural Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, Lebanese University, Hadath, Lebanon 3Le Corbusier 644, 280 Boulevard Michelet, 13008 Marseille, France 4Dipartimento di Biologia e Biotecnologie ‘Charles Darwin’, University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’, Viale dell’Università 32, 00185 Roma, Italy ABSTRACT: Lebanon (eastern Mediterranean Sea) is an area of particular biogeographic signifi- cance for studying the structure of eastern Mediterranean marine biodiversity and its recent changes. Based on literature records and original samples, we review here the knowledge of the Lebanese marine bivalve biota, tracing its changes during the last 170 yr. The updated checklist of bivalves of Lebanon yielded a total of 114 species (96 native and 18 alien taxa), accounting for ca. 26.5% of the known Mediterranean Bivalvia and thus representing a particularly poor fauna. Analysis of the 21 taxa historically described on Lebanese material only yielded 2 available names. Records of 24 species are new for the Lebanese fauna, and Lioberus ligneus is also a new record for the Mediterranean Sea. Comparisons between molluscan records by past (before 1950) and modern (after 1950) authors revealed temporal variations and qualitative modifications of the Lebanese bivalve fauna, mostly affected by the introduction of Erythraean species. The rate of recording of new alien species (evaluated in decades) revealed later first local arrivals (after 1900) than those observed for other eastern Mediterranean shores, while the peak in records in conjunc- tion with our samplings (1991 to 2010) emphasizes the need for increased field work to monitor their arrival and establishment. -

Data From: Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability

Portland State University PDXScholar Environmental Science and Management Datasets Environmental Science and Management 7-2019 Data From: Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability Britta Baechler Portland State University, [email protected] Elise F. Granek Portland State University, [email protected] Matthew V. Hunter Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Kathleen E. Conn United States Geological Survey Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/esm_data Part of the Environmental Health and Protection Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, and the Environmental Monitoring Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Baechler, Britta; Granek, Elise F.; Hunter, Matthew V.; and Conn, Kathleen E., "Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability" (2019). [Dataset]. https://doi.org/10.15760/esm-data.1 This Dataset is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Science and Management Datasets by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Metadata template1 for datasets of L&O-Letters articles Table 1. Description of the fields needed to describe the creation of your dataset. Title of dataset Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability URL of dataset Data is available in the Portland State University PDXScholar data repository at: https://doi.org/10.15760/esm-data.1 Abstract Microplastics are an ecological stressor with implications for ecosystem and human health when present in seafood. -

Electrical Phenomena at the Washington Monument

pebbles cemented n-ith mhite limestone, ancl gracl- that the mhole of the old becl is to some extent 1,er- nally changing upmarcl into a firm, barren, homoge- meatecl by the vatels of the unclergro~mclriver.- neous limestone. The extent and direction of this unclergro~~ncl This formation mas in continuation of, or some- channel, and the determination of other streams times below, the horizon of the Exogyra arietina than the Blanco which may be tapped by it, are marl. Here, then, mas the solution of the problem promising subjects of future investigation, which I of the San XIarcos. The rocks before me were of hope at an early clate to unclertake, not only in the the later cretaceous, deposited upon the gravel and hope of gaining, by a stuclp of the amount of erosion shingle -which had formecl the bed of a river during of the older rocks, some idea of the duration of the the period of emergence. They had choked up and interval betmeen the tmo periods of rock formation, rendered impervious the superficial layers of the but of obtaining some inforination concerniug the river-bed, but doubtless left the loner gravel and fresh-mater life of that period. EDTVIKJ. POND. sand beds in as gooil condition for carrying water as Austin. Tex., Nay 18. ever. To make the ericlence comolete. I found, on examination of the rock ma, whiih lies only a few Electrical phenomena at the Washington feet above the river, that it is the Soft limestone of the later cretaceous, containing numerous specimens monument. -

FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Fisheries and for a world without hunger Aquaculture Department Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme Mercenaria mercenaria (Linnaeus, 1758) I. Identity V. Status And Trends a. Biological Features VI. Main Issues b. Images Gallery a. Responsible Aquaculture Practices II. Profile VII. References a. Historical Background a. Related Links b. Main Producer Countries c. Habitat And Biology III. Production a. Production Cycle b. Production Systems c. Diseases And Control Measures IV. Statistics a. Production Statistics b. Market And Trade Identity Mercenaria mercenaria Linnaeus, 1758 [Veneridae] FAO Names: En - Northern quahog(=Hard clam), Fr - Praire, Es - Chirla mercenaria Biological features Shell solid, equivalve; inequilateral, beaks in the front half of the shell; broadly oval in outline. Ligament a deeply inset, dark brown elliptical band, behind the beaks reaching half-way to the posterior margin. Lunule well defined, broad, heart-shaped. Escutcheon indistinct. Sculpture of concentric lines, raised here and there into ridges, and fine radiating lines. In young specimens the ridges are present all over the shell but in the adult they persist, after wear and tear, only near the anterior and posterior margins. Growth stages prominent. Both valves with three cardinal teeth; in addition there is present in each valve a rough tooth-like area behind the beaks and immediately below the ligament; this area has the appearance of a supplementary posterior cardinal tooth which has been broken off. No laterals. Pallial sinus not deep, triangular. Margin grenulate. Colour a dirty white, light varnish-brown, dull grey or grey-brown. Inside of shell white, sometimes deep violet about the adductor muscle scars. -

Early Ontogeny of Jurassic Bakevelliids and Their Bearing on Bivalve Evolution

Early ontogeny of Jurassic bakevelliids and their bearing on bivalve evolution NIKOLAUS MALCHUS Malchus, N. 2004. Early ontogeny of Jurassic bakevelliids and their bearing on bivalve evolution. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 49 (1): 85–110. Larval and earliest postlarval shells of Jurassic Bakevelliidae are described for the first time and some complementary data are given concerning larval shells of oysters and pinnids. Two new larval shell characters, a posterodorsal outlet and shell septum are described. The outlet is homologous to the posterodorsal notch of oysters and posterodorsal ridge of arcoids. It probably reflects the presence of the soft anatomical character post−anal tuft, which, among Pteriomorphia, was only known from oysters. A shell septum was so far only known from Cassianellidae, Lithiotidae, and the bakevelliid Kobayashites. A review of early ontogenetic shell characters strongly suggests a basal dichotomy within the Pterio− morphia separating taxa with opisthogyrate larval shells, such as most (or all?) Praecardioida, Pinnoida, Pterioida (Bakevelliidae, Cassianellidae, all living Pterioidea), and Ostreoida from all other groups. The Pinnidae appear to be closely related to the Pterioida, and the Bakevelliidae belong to the stem line of the Cassianellidae, Lithiotidae, Pterioidea, and Ostreoidea. The latter two superfamilies comprise a well constrained clade. These interpretations are con− sistent with recent phylogenetic hypotheses based on palaeontological and genetic (18S and 28S mtDNA) data. A more detailed phylogeny is hampered by the fact that many larval shell characters are rather ancient plesiomorphies. Key words: Bivalvia, Pteriomorphia, Bakevelliidae, larval shell, ontogeny, phylogeny. Nikolaus Malchus [[email protected]], Departamento de Geologia/Unitat Paleontologia, Universitat Autòno− ma Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès), Spain. -

Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea Virginica)

Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica) Imagine yourself on the streets of Manhattan, hungry but short of time and money. You see a pushcart, place your order and are served a quick lunch of…..oysters! That’s right, oysters. Throughout the 19th and early 20th Centuries, New York City was an oyster-eating town with oyster barges lining the waterfront and oysters served and sold on the streets. The abundance of these tasty bivalves was a welcome food source for the Dutch and English colonists and oysters, exported back to Europe, quickly became a source of economic wealth. So many oysters were sold that paths and extended shorelines were built in New York City on crushed shells. Oysters have been a prominent species in the New York/New Jersey Harbor Estuary since the end of the Ice Age. They have been documented as a food source in the Estuary for as long as 8,000 years, based on evidence from Native American midden (trash) piles. Later, many of the Harbor Estuary’s shoreline communities developed and thrived on the oyster trade until it collapsed in the mid-1920s, although minor oyster fisheries survived at the Harbor Estuary’s Jamaica Bay fringes where the East River meets Long Island Sound until the late1930s or later. In the 1880’s it was estimated that oysters covered about 350 square miles or 250,000 acres of the Harbor Estuary’s bottom. They were found in mid-to lower salinity areas including the tidal rivers in New Jersey’s Monmouth County, Raritan Bay, up the lower Raritan River, throughout the Arthur Kill, Newark Bay, the lower Rahway, Passaic, and Hackensack Rivers, the Kill Van Kull, up both sides of the Hudson River into Haverstraw Bay, around New York City in the Harlem and East Rivers and in many smaller tributaries and Jamaica Bay.