Mark Twain Media/Carson-Dellosa Publishing LLC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book 1 Wilson, ND FIC WIL 0256HV2 100 People Who Made History

TitleWave # Title Author Dewey Subject 25034V2 1 2 3 :--a child's first counting book Jay, Alison. E JAY Counting 100 Cupboards: Book 1 Wilson, N.D. FIC WIL 0256HV2 100 people who made history :--meet the : Gilliland, Ben 920 GIL History 0240SF8 100 things you should know about explore North, Dan. 910.4 NOR Exploring 1001 Bugs to Spot Helbrough, Emma E HEL Bugs 17147Z4 101 animal secrets Berger, Melvin. 590 BER Animals 29655F2 11 birthdays Mass, Wendy, 1967- FIC MAS 29655F2 11 birthdays Mass, Wendy, 1967- FIC MAS 0464MJ2 13 American artists children should know: Finger, Brad. 709.73 FIN Art 0425HS4 13 art mysteries children should know Wenzel, Angela. 759 WEN Art 0116VF7 13 modern artists children should know Finger, Brad. 920 FIN Art 0498YG7 13 sculptures children should know Wenzel, Angela. 730 WEN Art 18th Century Clothing Kalman, Bobbie 391.0 KAL History: Clothing 07891Y9 18th century clothing Kalman, Bobbie. 391 KAL History: Clothing 30401V4 19 varieties of gazelle :--poems of the : Nye, Naomi Shihab 811 NYE Poetry 19th Century Clothing Kalman, Bobbie 391 KAL History: Clothing 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Verne, Jules FIC VER 0085EP2 8th grade superzero Rhuday-Perkovich, Olugbemi FIC RHU *YA 0342PZ7 A balanced diet Veitch, Catherine. 613.2 VEI Health A Bargain for Frances Hoban, Russell E HOB Picture Book 0454EV7 A black hole is not a hole DeCristofano, Carolyn Cina 523.8 DEC Space 29515RX A book about color Gonyea, Mark. 701 GON Art 38082C1 A cache of jewels and other collective n: Heller, Ruth, 1924- 428.1 HEL 31417W7 A chair for my mother Williams, Vera B. -

The Material World, Memory, and the Making of William Penn's Pennsylvania, 1681--1726

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2011 Building and Planting: The Material World, Memory, and the Making of William Penn's Pennsylvania, 1681--1726 Catharine Christie Dann Roeber College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Roeber, Catharine Christie Dann, "Building and Planting: The Material World, Memory, and the Making of William Penn's Pennsylvania, 1681--1726" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623350. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-824s-w281 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Building and Planting: The Material World, Memory, and the Making of William Penn's Pennsylvania, 1681-1726 Catharine Christie Dann Roeber Oxford, Pennsylvania Bachelor of Arts, The College of William and Mary, 1998 Master of Arts, Winterthur Program in Early American Culture, University of Delaware, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History The College of William and Mary August, 2011 Copyright © 2011 Catharine Dann Roeber All rights reserved APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ac#t~Catharine ~t-r'~~ Christie Dann Roeber ~----- Committee Chair Dr. -

INCOME TAX in COMMON LAW JURISDICTIONS: from the Origins

This page intentionally left blank INCOME TAX IN COMMON LAW JURISDICTIONS Many common law countries inherited British income tax rules. Whether the inheritance was direct or indirect, the rationale and origins of some of the central rules seem almost lost in history. Commonly, they are simply explained as being of British origin without further explanation, but even in Britain the origins of some of these rules are less than clear. This book traces the roots of the income tax and its precursors in Britain and in its former colonies to 1820. Harris focuses on four issues that are central to common law income taxes and which are of particular current relevance: the capitalÀrevenue distinction, the taxation of corporations, taxation on both a source and residence basis, and the schedular approach to taxation. He uses an historical per- spective to make observations about the future direction of income tax in the modern world. Volume II will cover the period 1820 to 2000. PETER HARRIS is a solicitor whose primary interest is in tax law. He is also a Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Law of the University of Cambridge, Deputy Director of the Faculty’s Centre for Tax Law, and a Tutor, Director of Studies and Fellow at Churchill College. CAMBRIDGE TAX LAW SERIES Tax law is a growing area of interest, as it is included as a subdivision in many areas of study and is a key consideration in business needs throughout the world. Books in this Series will expose the theoretical underpinning behind the law to shed light on the taxation systems, so that the questions to be asked when addressing an issue become clear. -

Application of Link Integrity Techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science Department of Electronics and Computer Science A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD Supervisor: Prof. Wendy Hall and Dr Les Carr Examiner: Dr Nick Gibbins Application of Link Integrity techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web by Rob Vesse February 10, 2011 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND APPLIED SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD by Rob Vesse As the Web of Linked Data expands it will become increasingly important to preserve data and links such that the data remains available and usable. In this work I present a method for locating linked data to preserve which functions even when the URI the user wishes to preserve does not resolve (i.e. is broken/not RDF) and an application for monitoring and preserving the data. This work is based upon the principle of adapting ideas from hypermedia link integrity in order to apply them to the Semantic Web. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Hypothesis . .2 1.2 Report Overview . .8 2 Literature Review 9 2.1 Problems in Link Integrity . .9 2.1.1 The `Dangling-Link' Problem . .9 2.1.2 The Editing Problem . 10 2.1.3 URI Identity & Meaning . 10 2.1.4 The Coreference Problem . 11 2.2 Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1 Early Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1.1 Halasz's 7 Issues . 12 2.2.2 Open Hypermedia . 14 2.2.2.1 Dexter Model . 14 2.2.3 The World Wide Web . -

Colonial America

Grade 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® • Listening & Learning™ Strand Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Anthology Read-Aloud Again!™ It Tell Colonial America Colonial Colonial America Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Anthology Listening & Learning™ Strand GRADE 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. You are free: to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work to Remix — to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike — If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Copyright © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts, Listening & Learning, and Tell It Again! are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. -

13 Colonies Reading Comprehension Series Available On

13 Colonies Reading Comprehension Series Available on: MrN365.com Teachers Pay Teachers Terms of Use: • Purchaser cannot share product with other teachers, parents, tutors, or other products, who have not themselves purchased products or subscription to MrN365.com. • Purchaser cannot re-sell product or extract passage, questions, or other information from the product for use in other materials including websites, standardized tests, workbooks, publications, mailings, or apps. • Purchaser cannot post product online without the expressed written consent from Nussbaum Education Network, LLC • Passages and question sets (product) can be used by a single purchaser and associated students. Product can be distributed to students. • Any other uses not described here require written permission from Nussbaum Education Network, LLC The Connecticut Colony Connecticut was originally settled by Dutch fur traders in 1614. They sailed up the Connecticut River and built a fort near present-day Hartford. The first English settlers were Puritans from the Massachusetts Bay Colony who arrived in Connecticut in 1633 under the leadership of Reverend Thomas Hooker. After their arrival, several colonies were established including the Colony of Connecticut, Old Saybrooke, Windsor, Hartford, and New Haven. Hartford quickly became an important center of government and trade. Much of the land settled by the colonists was purchased from the Mohegan Indians. The Pequot tribe, however, wanted the land. Soon, violence erupted between settlers and the Pequots in 1637. In what came to be known as the Pequot War, the Pequots were systematically massacred by not only the settlers, but by Mohegan and Naragansett Indians that had previously warred against them. -

DELAWARE COLONY Reading Comprehension

DELAWARE COLONY Reading Comprehension The Dutch first settled Delaware in 1631, although all of the original settlers were killed in a disagreement with local Indians. Seven years later, the Swedes set up a colony and trading post at Fort Christina in the northern part of Delaware. Today, Fort Christina is called Wilmington. In 1651, the Dutch reclaimed the area and built a fort near present-day New Castle. By 1655, the Dutch had forcibly removed the Swedes from the area and reincorporated Delaware into their empire. In 1664, however, the British removed the Dutch from the East Coast. After William Penn was granted the land that became Pennsylvania in 1682, he persuaded the Duke of York to lease him the western shore of Delaware Bay so that his colony could have an outlet to the sea. The Duke agreed and henceforth, Penn's original charter included the northern sections of present-day Delaware, which became known as "The Lower Counties on the Delaware." The decision by the Duke angered Lord Baltimore, the first proprietary governor of Maryland, who believed he had the rights to it. A lengthy and occasionally violent 100-year conflict between Penn's heirs and Baltimore's heirs was finally settled when Delaware's border was defined in 1750 and when the Maryland/Pennsylvania and Maryland/Delaware borders were defined as part of the Mason-Dixon line in 1768. Shortly after the incorporation of the "Lower Counties" into Pennsylvania, the sparsely populated region grew isolated from the bustling city of Philadelphia and began holding their own legislative assemblies, though they remained subjects of the Pennsylvania governor. -

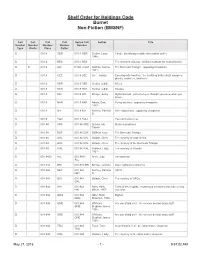

Shelf Order for Holdings Code Burnet Non-Fiction (BMSNF)

Shelf Order for Holdings Code Burnet Non-Fiction (BMSNF) Call Call Call Call Sorted Call Author Title Number Number Number Number Number Type Prefix Class Cutter D 001.4 GER 001.4 GER Gerber, Larry, Cited! : identifying credible information online 1946- D 001.4 RES 001.4 RES The research virtuoso : brilliant methods for normal brains D R 001.9 Gaf R 001.9 Gaf Gaffron, Norma, The Bermuda Triangle : opposing viewpoints 1931- D 001.9 GEE 001.9 GEE Gee, Joshua Encyclopedia horrifica : the terrifying truth! about vampires, ghosts, monsters, and more D 001.9 HER 001.9 HER Herbst, Judith. Aliens D 001.9 HER 001.9 HER Herbst, Judith. Hoaxes D 001.9 KRI 001.9 KRI Krieger, Emily Myths busted! : just when you thought you knew what you knew-- D 001.9 NAR 001.9 NAR Nardo, Don, Flying saucers : opposing viewpoints 1947- D 001.9 Net 001.9 Net Netzley, Patricia Alien abductions : opposing viewpoints D. D 001.9 YOU 001.9 YOU You can't scare me!. D 001.94 ANS 001.94 ANS Ansary, Mir Mysterious places Tamim D 001.94 DUF 001.94 DUF Duffield, Katy The Bermuda Triangle D 001.94 OXL 001.94 OXL Oxlade, Chris The mystery of crop circles D 001.94 OXL 001.94 OXL Oxlade, Chris The mystery of the Bermuda Triangle D 001.94 WAL 001.94 WAL Wallace, Holly, The mystery of Atlantis 1961- D 001.9403 ALL 001.9403 Allen, Judy Unexplained ALL D 001.942 BRI 001.942 BRI Bringle, Jennifer Alien sightings in America D 001.942 NET 001.942 Netzley, Patricia UFO's NET D. -

Colonies Take Root 1587 - 1752

Colonies Take Root 1587 - 1752 Cold winters, short growing season, and a rugged landscape Temperate climate, longer growing season, lowland landscape of fields and valleys Warm climate, long growing season, landscape with broad fields and valleys Geography lent itself to fishing, lumber harvesting, and small-scale subsistence farming. Known as the “bread basket” of the colonies for exporting staple crops, such as wheat and grain Exported the labor-intensive cash crops of tobacco, rice, and indigo New England Colonies Life in was not easy. Because the growing season was short and the soil was rocky, most farmers practiced . They produced enough food for themselves and sometimes a little extra to trade in town. New England villages developed in a unique way. Large plots of land were sold to groups of people, often the congregation of a Puritan church. Congregations divided the land among their members. Usually a cluster of farmhouses surrounded a central square, called a green or common, and a meeting- house where public activities took place. Changes in Puritan Society The Puritan religion began a gradual decline in the early 1700s. The three factors led to this decline. 1. Economic success competed with Puritan Ideas. Many colonists began to care as much about business and material things as much as they did about religion. 2. Increasing competition from other religious groups. Baptists and Anglicans established churches in New England. 3. Political changes also weakened the Puritan community. New charters guaranteed religious freedom and granted the right to vote based on property ownership instead of church membership. Major Industries of New England ECONOMIC BENEFITS TO ACTIVITY COLONISTS Fishing Fish could be sold for consumption or export. -

8089 Globe Drive | Woodbury, MN 55125 | Wlamn.Org Big Idea the Three Regions of English Colonies on the Eastern Seaboard Develop

Domain-Based Unit Overview Title of Domain: The Thirteen Colonies: Life and Times Before the Revolution, Grade 3 Learning Time: 35 days Big Idea The three regions of English colonies on the eastern seaboard developed differently for a variety of reasons. (p.174) What Students Need to Learn (p.174) ● Explain the differences in climate and agriculture among the three colonial regions ● Locate the thirteen colonies and important cities, such as Philadelphia, Boston, New York, Charleston qu ● Southern Colonies: ○ Locate and identify importance of Virginia, Maryland, South Carolina, Georgia ○ Describe the story of Jamestown ○ Identify the founders of these colonies, their reliance on slavery and cash crop ○ Describe the Middle Passage ● New England Colonies: ○ Locate and identify importance of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island ○ Describe the two groups that settled in Massachusetts: Pilgrims and Puritans ○ Explain the development of maritime economy and the influence of religion ● Middle Atlantic Colonies: ○ Locate and identify importance of New York, New Jersey, Delaware ○ Describe the successes of the Dutch in New York ○ Identify importance of William Penn and the Quakers in Pennsylvania MN Academic Standards 3.4.1.2.1- Examine historical records, maps and artifacts to answer basic questions about times and events in history, both ancient and more recent. 3.4.1.1.2- Create timelines of important events in three different tie scales- decades, centuries and millennia. 3.4.2.5.1- Identify examples of individuals or groups who have had an impact on world history; explain how their actions helped shape the world around them. 8089 Globe Drive | Woodbury, MN 55125 | wlamn.org 3.4.3.9.1- Compare and Contrast daily life for people living in ancient times in at least three different regions of the world. -

The Newark Post 'Volu;\IE Xx NEWARK, DELAWARE, THURSDAY OCTOBER 17 1929 NUMBER 88

/ • The Newark Post 'VoLU;\IE xx NEWARK, DELAWARE, THURSDAY OCTOBER 17 1929 NUMBER 88 ARS SMASHED Town Library Drive STREET PROGRAM WILL HONOR DEL. Historical Edition CHIEF CAPTURES The membership committee, The Newark Post is now ac IN ACCIDENTS which has been conducting a ABOUT COMPLETE D. A. R. REGENT cumulating data for a special HEAVILY ARMED campaign this week for member historical edition of this locality, ships in the Town Library, re which will be published the lat ports an excellent response and Difficulties Encountered In Mrs. Cooch----- Will Lead Proces- ter part of the month. It will NEGRO GUNMAN Laying South Chapel Street sion Of National Officers appreciate any stories, anec ~:~~c:~e t~f c~~P:~~i ~~cc~~!~~i dotes or little known historical Th'~ ~,OB3~~~a~~~1 drives ever undertaken for the Storm Sewer Have Re- And State Regents At Dedi- Keeley Makes Daring Arres Acc idents In Newark During facts, which may be sent in by local library. tarded Progress cation Services In Washing- contributors. Old records will At Cannery Following At Week , But Occupants All Membership in the Library, be carefully taken care of and which is in the Old Academy ton returned. tempted Murder; Disarm Escape Inj ury; One Driver $400 Building, is $1.00 per year. The The town engineer, Merle Sigmund: ----,. Negro W'ho Had Drop On 290 Fined library is supported by these reports that the laying of the curb Mrs. Edward W. Cooch, of Cooch's Him 495 memberships and by help jrom and gutter in the fall street improve- Bridge, State Regent of the D. -

British Colonization of the Americas from Wikipedia, the Free

British colonization of the Americas From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from British colonisation of the Americas) European colonization of the Americas First colonization British Couronian Danish Dutch French German Hospitaller Italian Norse Portuguese Russian Scottish Spanish Swedish Colonization of Canada Colonization of the U.S. Decolonization v t e British colonization of the Americas (including colonization by both the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland before the Acts of Union, which created the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707) began in 1607 in Jamestown, Virginia and r eached its peak when colonies had been established throughout the Americas. The English, and later the British, were among the most important colonizers of the Americas, and their American empire came to rival the Spanish American colonies in military and economic might. Three types of colonies existed in the British Empire in America during the heig ht of its power in the eighteenth century. These were charter colonies, propriet ary colonies and royal colonies. After the end of the Napoleonic Wars (18031815), British territories in the Americas were slowly granted more responsible govern ment. In 1838 the Durham Report recommended full responsible government for Cana da but this did not get fully implemented for another decade. Eventually with th e Confederation of Canada, the Canadian colonies were granted a significant amou nt of autonomy and became a self-governing Dominion in 1867. Other colonies in t he rest of the Americas followed at a much slower pace. In this way, two countri es in North America, ten in the Caribbean, and one in South America have receive d their independence from the United Kingdom.