Agribusiness Development Clusters, Sezs and Incubators: Highlights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Causas De Las Crisis Alimentarias En Somalia, Sudán Y Etiopía Entre 1980 Y 2015

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS Y EMPRESARIALES DEPARTAMENTO DE ECONOMÍA APLICADA I TESIS DOCTORAL Causas de las crisis alimentarias en Somalia, Sudán y Etiopía entre 1980 y 2015 MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Francisco Jesús Gómez de Mercado Millán DIRECTOR Jorge Fonseca Castro Madrid, 2018 © Francisco Jesús Gómez de Mercado Millán, 2017 UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS Y EMPRESARIALES Departamento de Economía Aplicada I CAUSAS DE LAS CRISIS ALIMENTARIAS EN SOMALIA, SUDÁN Y ETIOPÍA ENTRE 1980 Y 2015 TESIS DOCTORAL PRESENTADA POR FRANCISCO JESÚS GÓMEZ DE MERCADO MILLÁN BAJO LA DIRECCIÓN DEL DOCTOR JORGE FONSECA CASTRO Madrid, 2017 Causas de las crisis alimentarias en Somalia, Sudán y Etiopía entre 1980 y 2015 Agradecimientos Deseo expresar mi agradecimiento, en primer lugar, a don Jorge Fonseca Castro, director de esta tesis y de la Catedra "Celso Furtado" de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, así como al resto de profesores del Master de Economía Internacional y Desarrollo de la UCM por sus enseñanzas durante todos estos años. 3 Causas de las crisis alimentarias en Somalia, Sudán y Etiopía entre 1980 y 2015 A mi mujer 5 Causas de las crisis alimentarias en Somalia, Sudán y Etiopía entre 1980 y 2015 Resulta tremendamente irónico que la mitad de las personas que pasan hambre en el mundo se dediquen a la agricultura. Devereux, Vaitla y Hauenstein-Swan (2008, 26). 7 Causas de las crisis alimentarias en Somalia, Sudán y Etiopía entre 1980 y 2015 RESUMEN -

Measuring the Rural Transport Premium in Murang'a County, Kenya

Measuring the Rural Transport Premium in Murang’a County, Kenya Final Report Tacitus Ltd GEN2185B June 2020 The Developmental Participatory Consultants Preferred citation: Orwa, S., and Oyoo, R. (2020). Measuring the Rural Transport Premium in Kenya: Final Report, GEN2185B. London: ReCAP for DFID. For further information, please contact Samuel Orwa, [email protected] ReCAP Project Management Unit Cardno Emerging Market (UK) Ltd Level 5, Clarendon Business Centre 42 Upper Berkeley Street, Marylebone London W1H 5PW United Kingdom The views in this document are those of the authors and they do not necessarily reflect the views of the Research for Community Access Partnership (ReCAP) or Cardno Emerging Markets (UK) Ltd for whom the document was prepared Cover photo: Gitugi -Shopping Centre – Picture by Robert Oyoo Quality assurance and review table Version Author(s) Reviewer(s) Date 1.0 Samuel Orwa and Robert Oyoo Annabel Bradbury (ReCAP PMU) 16/06/2020 Joseph Haule (ReCAP PMU 22/06/2020 2.0 Samuel Orwa and Robert Oyoo Annabel Bradbury (ReCAP PMU) 02/07/2020 ReCAP Database Details: Measuring the Rural Transport Premium in Murang’a County, Kenya Reference No: GEN2185B Location Kenya Samuel Orwa Procurement Sole sourced Source of Proposal Method Theme Transport Services Sub-Theme Rural Transport Impact Indicators Lead Tacitus Ltd N/A Partner Implementation Organisation Organisation Total Approved GBP 4,800 GBP 4,800 Total Used Budget Budget Start Date 24 February 2020 End Date 30 June 2020 Report Due Date 15 June 2020 Date Received 15 June 2020 ReCAP | Measuring the Rural Transport Premium in Kenya 3 Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

A Farming Systems Research Bibliography of Kansas State University's Vertical File Materials

A FARMING SYSTEMS RESEARCH BIBLIOGRAPHY OF KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY'S VERTICAL FILE MATERIALS. REVISED. Gretchen A. Graham, Editor* Paper No. 4. Revised July 1986 Resources on Developing Countries Farrell Library Kansas State University Manhattan, Kansas 66506 U.S.A. *Data entry and data base programming by Susan Powell, Research Assistant and Master Candidate, Dept. of Computer Science, KSU. 2005 Digital Edition Kansas State University Digital Library Department FARMING SYSTEMS RESEARCH PAPER SERIES Kansas State University’s Farming Systems Research (FSR) Paper Series is supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development Title XII Program Support Grant. The goal of the Program Support Grant is to increase the University’s ability to implement Title XII agricultural and nutritional development assistance programs in less-developed countries. This paper series is maintained by the FSR Program Associates -- a multidisciplinary team of professors who are aiming their activities at applied research on farming from a systems perspective. The purpose of the FSR Paper Series is to disseminate infor- mation on FSR. Publication categories include updated bibliographies from KSU’s FSR data base; proceedings from KSU’s FSR Systems Symposium; selected papers presented in KSU’s FSR Seminar Series; selected papers prepared by KSU’s Programs Associates. Vernon C. Larson Director International Agricultural Programs NOTICE OF NONDISCRIMINATION Kansas State University is committed to a policy of non-discrimination on the basis of race, sex, national origin, handicap, or other non-merit reasons, in admissions, educational programs or activities, and employ- ment, all as required by applicable laws and regulations. Responsibility for coordination of compliance efforts and receipt of inquiries, including those concerning Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, has been delegated to Jane D. -

Kenya Health Workforce Report: the Status of Healthcare Professionals in Kenya, 2015 Collaborating Institutions

Kenya Health Workforce Report: The Status of Healthcare Professionals in Kenya, 2015 Collaborating Institutions Kenya Ministry of Health (MOH) Radiation Protection Board (RPB) Medical Practitioners and Dentist Board Society of Radiographers of Kenya (SORK) (MPDB) Public Health Officers and Technicians Nursing Council of Kenya (NCK) Council (PHOTC) Clinical Officers Council (COC) Kenya Health Workforce Project (KHWP) Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) Emory University Kenya Medical Laboratory Technicians and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Technologists Board (KMLTTB) Prevention (CDC) Kenya Nutritionists and Dieticians Institute (KNDI) Donor Support This report was supported under a cooperative agreement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Coordinating Office of the Center for Global Health (CGH) Division of Global HIV and TB (DGHT) through the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH) Grant Number U36OE000002 to Emory University, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC or ASPPH. Contact Information Ministry of Health Afya House, Cathedral Road P.O. Box 30016, Tel. 2717077, Nairobi http://www.health.go.ke Medical Practitioners and Dentist Board (MPDB) www.medicalboard.co.ke Nursing Council of Kenya (NCK) www.nckenya.com Clinical Officers Council (COC) www.clinicalofficerscouncil.org Pharmacy and Poisons Board (PPB) www.pharmacyboardkenya.org Kenya Medical Laboratory -

Quick Scan of Kenya's Forage Sub-Sector

Quick Scan of Kenya’s Forage Sub-Sector Netherlands East African Dairy Partnership (NEADAP) Working Paper Nairobi - July 2019 Authors: Jos Creemers (SNV Kenya) Adolfo Alvarez Aranguiz (Wageningen UR, Livestock Research) Kenya Forage Sub-Sector Quick Scan – Working Paper – NEADAP, July 2019 ii Quick Scan of Kenya’s Forage Sub-Sector Working Paper Netherlands East African Dairy Partnership (NEADAP) Jos Creemers - SNV Kenya Adolfo Alvarez Aranguiz - Wageningen UR, Livestock Research This document or Working Paper describes Kenya’s forage sub-sector and looks at the current situation of available forage species and their quality, seasonality, preservation, forage seeds and planting material, fertilizer use, mecha- nisation, inputs and services, the forage market, education and training, innovations, environmentally sustainable forage production and policies and regulations affecting the forage sub-sector. The Working Paper identifies gaps and gives recommendations to enhance availability of quality forages. It is a reference document for the development of a Strategy Paper and/or Policy Brief under Theme 2: Forages and nutrition of dairy cows, of the Netherlands East African Dairy Partnership project (NEADAP). NEADAP is an initiative by the Netherlands government for learning and sharing amongst different dairy sectors and projects in East Africa. This report can be downloaded free of charge from www.cowsoko.com/KMDP and from https://edepot.wur.nl/504126. The user may copy, distribute and transmit the work and create derivative works. Third-party material that has been used in the work and to which intellectual property rights apply, may not be used without prior permission of the third party concerned. The user must specify the name as stated by the author or license holder of the work, but not in such a way as to give the impression that the work of the user or the way in which the work has been used are being endorsed. -

Agrodiversity: Learning from Farmers Across the World

The United Nations University is an organ of the United Nations estab- lished by the General Assembly in 1972 to be an international community of scholars engaged in research, advanced training, and the dissemination of knowledge related to the pressing global problems of human survi- val, development, and welfare. Its activities focus mainly on the areas of peace and governance, environment and sustainable development, and science and technology in relation to human welfare. The University oper- ates through a worldwide network of research and postgraduate training centres, with its planning and coordinating headquarters in Tokyo. The United Nations University Press, the publishing division of the UNU, publishes scholarly and policy-oriented books and periodicals in areas related to the University’s research. Agrodiversity This book presents part of the findings of the international project “People, Land Management, and Environmental Change”, which was initiated in 1992 by the United Nations University. From 1998 to 2002, the project was supported by the Global Environment Facility with the United Nations Environment Programme as implementing agency and the United Nations University as executing agency. The views expressed in this book are entirely those of the respective authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Global Environment Facility, the United Nations Environment Programme, and the United Nations University. Agrodiversity: Learning from farmers across the world Edited by Harold Brookfield, Helen Parsons, and Muriel -

Effect of Cobalt, Molybdenum and Rhizobium on Yield of Soya Beans in Kisii County, Kenya

International Journal For Research In Agricultural And Food Science ISSN: 2208-2719 Effect of Cobalt, Molybdenum and Rhizobium on Yield of Soya Beans in Kisii County, Kenya. Ombuna Dorice1 , Mworia Mugambi2, Muchiri John3 123 Kenya Methodist University. Department of Agriculture and Rural Development Email: [email protected], mworia. mugambi @kemu.ac.ke, john.muchiri @kemu.ac.ke Correspondence: Dorice Omwocha, : Email: [email protected] Abstract. Introduction: Soybean is a leading source of protein and oil used for human consumption and livestock feed, also considered a valuable crop globally. The leading producers worldwide are United States of America, Brazil and China that produce as high as 89.9 Million tonnes annually. In Kenya, the beans are mainly grown in the western and central regions of Kenya, and the average yield is 363 kgha-1. This is low compared to the other countries, the poor yield in Kisii County is associated to low soil fertility, poor agronomic practices and acidified soil. Additionally, insufficient nitrogen and phosphorus in soil, use of unimproved seed varieties and poor management practices are causes. Objectives: The study aimed at evaluating the effects of molybdenum, cobalt and rhizobium inoculants on yield of soya beans in Kisii County. Research methodology: A randomised complete block design experiment was carried out at Kisii Agricultural Training Centre. Seeds were coated with ttreatments that included: Control (WT), DAP, Rhizoliq Top Soya 3m/kg, Wuxal Extra COMO1.5 at 1m/kg of seed, Wuxal Extra COMO 1.5 at 1.5 mls/kg of seed, (Wuxal Extra COMO 1.5 at 1.5 mls/kg / Rhilizic top 3mls) and (Waxul Extra15 COMO1m/Rhizoliq top 3ml/kg) of soya seed. -

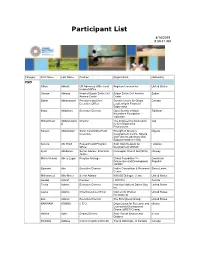

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana -

Género Y Legislación

76 ISSN 1020-4377 Rev. 1 FAO ESTUDIO LEGISLATIVO 76 Rev. 1 Género y legislación – Los derechos de la mujer en agricultura derechos – Los y legislación Género Género y legislación Las mujeres constituyen una parte sustancial de la población económicamente activa dedicada a la agricultura. Los instrumentos internacionales de derechos humanos, Los derechos de la mujer medioambiente y desarrollo sostenible proclaman el principio de no discriminación por razón de sexo o de género. Sin embargo las mujeres frecuentemente se encuentran con obstáculos de género a la hora de ejercer sus derechos y de alimentar a sus familias. en la agricultura Así, el derecho a un nivel de vida adecuado, que incluye una alimentación adecuada, puede verse vulnerado. Estos obstáculos pueden derivarse de normas directa o indirectamente discriminatorias, de prácticas socioculturales profundamente arraigadas o de ambas cosas. El presente estudio analiza desde una perspectiva de género la legislación relativa a la agricultura existente en distintos países del mundo, examinando la condición jurídica de la mujer en tres esferas clave: los derechos sobre la tierra y los recursos naturales; los derechos de las trabajadoras agrícolas; y los derechos de las trabajadoras autónomas del sector agrario, desde la condición de la mujer en las cooperativas rurales hasta su acceso a los servicios de crédito, capacitación y extensión agrícola. ISBN 978-92-5-305563-0 ISSN 1020-4377 978 9 2 5 3 0 5 5 6 3 0 FAO TC/M/A0686S/1/05.07/1000 FAO ESTUDIO Género y legislación LEGISLATIVO Los -

Management of Trees Used in Mursik (Fermented Milk) Production in Trans-Nzoia District, Kenya

Journal of Ethnobiology 20(1): 75-91 Summer 2000 MANAGEMENT OF TREES USED IN MURSIK (FERMENTED MILK) PRODUCTION IN TRANS-NZOIA DISTRICT, KENYA WILLIAM MUREITHI Department ofForestry, Moi University, P.O. Box 1125, E/doret Kenya CHRlSTOFFEL DEN BIGGELAAR Department ofInterdisciplinary Studies 109-B East Hall Appalachian State University Boone, NC 28608 USA EDWARD W. WESAKANIA and KURlA KAMAU Kaisagat Environmental Conservation Youth Group PO. Box 119, Kipsaina via Kitale Kenya CATHERINE GATUNDU Forest Action Network P.O. Box 21428, Nairobi Kenya ABsTRACT.- Milk treatment using trees is an age-old practice of both sedentary and nomadic pastoral communities in Kenya. Due to economic, political and environmental pressures, many pastoralists have become settled farmers and turned to crop cultivation as their main means of survival. However, they have continued to keep some cows and to treat their milk using traditional practices, incorporating the desired tree species into their farming system. This paper presents information as to how species are identified and selected, how the trees are managed, management problems associated with the trees, and how farmers evaluate the results of continuing experimentation with trees used for mllrsik production. Key words: Fermented milk, /nllrsik, pastoralism, farming, Kenya REsUMEN.-Tratamiento de leche usando arboles es una antigua practica de comunidades pastoriles sedentario y n6madas en Kenya. Par la influencia econ6mico, poHtica y ambiental, muchos ganaderos se haeen agricultores y se mantienen con las cultivaci6n de comida c6mo su superviviente. Ademas, elias siguen manteniendo vacas y tratando la leche con practicos tradicionales, incorporando los arboles neeesarios en su sistema de agricultura. Este papel va 76 MUREITHI ('I al. -

Plantation Struggles in Kenya: Trade Unionism on the Land 1947-63

Doctoral Thesis Plantation Struggles in Kenya: Trade Unionism on the Land 1947-63 David Nicholas Hyde Department of History School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2000 ProQuest Number: 10731711 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731711 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The following work examines the making of Kenya’s plantation proletariat and its social physiognomy in Thika and Kiambu districts from the late forties to the mid sixties. The work proceeds from the value relations of the coffee commodity on the world market and then to production relations within the districts concerned. Select estates within these areas are then identified in order to trace the workings of the law of value from its appearance as prices in the world market to the origins ofsurplus value and struggles over its extraction within the workplace. The increased rate of exploitation tliroughout the plantation economy is then identified as the principal subterranean impulse to workers’ recourse to trade unionism. -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Pobushed by Authority of the Repnbhc of Kenya

THE KENYA GAZETTE PobUshed by Authority of the Repnbhc of Kenya (Regntered as a Newspaper at the G P 0 ) Vol. LXIX-No. 33 NAIROBI, 30th June 1967 Price Sh 1/50 CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICES GAZETTENo~~c~s-(Contd ) PAGB 1 PAGE The Interpletatlon and Genelal P~ovlslons Act- TI anspol t Llcenslng Tempolaly Tlan5fel of Powers 684 ?veb-te and Asdm n t at e The Commlsslons of Inquliy Act-Amendlng Comrnlsslon 684 Revocation of Power of Attoiney The Const~tution of the Repubhc of Kenya-Appolnt ment 684 Bmkl uptcy Jurlsdlctlon The T~adeUnlons Tllhunal (Procedu~e) Rules 1964- The Companies Act-Notice of Intention to Dlssolve Appointment 684 Companies 700 The Forests Act-Appointment 684 The Socletles Act-Reglstlatlons, etc The Ltnd Acqulsltlon Act, 1894, of Indr-Appointment, Tendel s et~ 684 Local Govetnment Notlces The Crlm~nalPlocedule Code-Appointments 684 Notlce of Closule of Roads The Regulatlon of Wages and Condltlons of Employ ment Act-Appointments, etc 685 Busmess Tlansfers The Oaths and Statutory Declarations AL~-A Ch-tnge of Name Comm~ss~on 685 The National Assembly and Local Government Electlons Order 1967 685 I SUPPLEMENT No 51 The Court of Appeal foi Eastern Afnca-Vacatlon Dates 685 Legrslatzve Supplement The Agriculture Act-Dlrectlons 685 LEGALNOTICE NO PAOE The Cotton Act-Buylng Centres and Dates 686 174-The Local Government Electlons (Amendment) Rules 1967 199 The Mlnlng Regulations-Explry of Locatlon 686 135-The Teachers Servlce Commlsslon Act 1966- The Reglstrat~on of Tltles Act-Grant of Letters of Notlce of Commencement 199 Admlnlstratlon,