Partnership Profile: Gavi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLINICAL TRIALS Safety and Immunogenicity of a Nicotine Conjugate Vaccine in Current Smokers

CLINICAL TRIALS Safety and immunogenicity of a nicotine conjugate vaccine in current smokers Immunotherapy is a novel potential treatment for nicotine addiction. The aim of this study was to assess the safety and immunogenicity of a nicotine conjugate vaccine, NicVAX, and its effects on smoking behavior. were recruited for a noncessation treatment study and assigned to 1 of 3 doses of the (68 ؍ Smokers (N nicotine vaccine (50, 100, or 200 g) or placebo. They were injected on days 0, 28, 56, and 182 and monitored for a period of 38 weeks. Results showed that the nicotine vaccine was safe and well tolerated. Vaccine immunogenicity was dose-related (P < .001), with the highest dose eliciting antibody concentrations within the anticipated range of efficacy. There was no evidence of compensatory smoking or precipitation of nicotine withdrawal with the nicotine vaccine. The 30-day abstinence rate was significantly different across with the highest rate of abstinence occurring with 200 g. The nicotine vaccine appears ,(02. ؍ the 4 doses (P to be a promising medication for tobacco dependence. (Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005;78:456-67.) Dorothy K. Hatsukami, PhD, Stephen Rennard, MD, Douglas Jorenby, PhD, Michael Fiore, MD, MPH, Joseph Koopmeiners, Arjen de Vos, MD, PhD, Gary Horwith, MD, and Paul R. Pentel, MD Minneapolis, Minn, Omaha, Neb, Madison, Wis, and Rockville, Md Surveys show that, although about 41% of smokers apy, is about 25% on average.2 Moreover, these per- make a quit attempt each year, less than 5% of smokers centages most likely exaggerate the efficacy of are successful at remaining abstinent for 3 months to a intervention because these trials are typically composed year.1 Smokers seeking available behavioral and phar- of subjects who are highly motivated to quit and who macologic therapies can enhance successful quit rates are free of complicating diagnoses such as depression 2 by 2- to 3-fold over control conditions. -

Immunization Policies and Procedures Manual

Immunization Policies and Procedures Manual Louisiana Department of Health Office of Public Health Immunization Program Revised September 2017 i Center for Community and Preventive Health Bureau of Infectious Diseases Immunization Program TABLE OF CONTENTS I. POLICY AND GENERAL CLINIC POLICY ............................................................................................................................. 1 PURPOSE ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 POLICY ON CLINIC SCHEDULING ............................................................................................................................................ 2 POLICY ON PUBLICITY FOR IMMUNIZATION ACTIVITIES .............................................................................................. 4 POLICY ON EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES (HEALTH EDUCATION IN IMMUNIZATION CLINICS) .......................... 5 POLICY ON CHECKING IMMUNIZATION STATUS OF ALL CHILDREN RECEIVING SERVICES THROUGH THE HEALTH DEPARTMENT ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 POLICY ON MAXIMIZING TIME SPENT WITH PARENTS DURING IMMUNIZATION CLINICS ............................... 7 POLICY ON ASSISTANCE TO FOREIGN TRAVELERS .......................................................................................................... 9 II. POLICY -

UNICEF Immunization Roadmap 2018-2030

UNICEF IMMUNIZATION ROADMAP 2018–2030 Cover: ©UNICEF/UN065768/Khouder Al-Issa A health worker vaccinates 3-year-old Rahaf in Tareek Albab neighborhood in the eastern part of Aleppo city. UNICEF IMMUNIZATION ROADMAP 2018–2030 Photograph credits: Pages vi-vii: © Shutterstock/thi Page 5: © UNICEF/UN060913/Al-Issa Page 6: © UNICEF/UNI41364/Estey Page 10: © UNICEF/UN061432/Dejongh Page 14: © UNICEF/UNI76541/Holmes Page 18: © UNICEF/UN0125829/Sharma Page 24: © UNICEF/UN059884/Zar Mon Page 26: © UNICEF/UN065770/Al-Issa Page 33: © UNICEF/UN0143438/Alhariri Page 34: © UNICEF/UNI45693/Estey Page 38: © UNICEF/UNI77040/Holmes Page 40: © UNICEF/UN0125861/Sharma Page 44: © UNICEF/UNI41211/Holmes © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), September 2018 Permission is required to reproduce any part of this publication. Permission will be freely granted to educational or non-profit organizations. Please contact: Health Section, Immunization Team UNICEF 3 United Nations Plaza New York, NY 100017 Contents Abbreviations viii Executive summary 1 1. Introduction 7 1.1 Background 7 1.2 Developing the Roadmap 9 2. Key considerations informing the UNICEF Immunization Roadmap 11 2.1 Key drivers of immunization through 2030 11 2.2 Evolving immunization partnerships 15 2.3 UNICEF’s comparative advantage in immunization 16 3. What is new in this Roadmap? 19 3.1 Immunization coverage as a tracer indicator of child equity 19 3.2 Key areas of work 21 4. Roadmap programming framework 27 4.1 Vision and impact statements 27 4.2 Programming principles 27 4.3 Context-driven responses 27 4.4 Objectives and priorities 29 4.5 Populations and platforms 32 4.6 Country-level immunization strategies 32 5. -

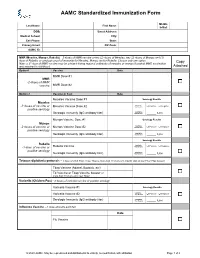

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form Middle Last Name: First Name: Initial: DOB: Street Address: Medical School: City: Cell Phone: State: Primary Email: ZIP Code: AAMC ID: MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) – 2 doses of MMR vaccine or two (2) doses of Measles, two (2) doses of Mumps and (1) dose of Rubella; or serologic proof of immunity for Measles, Mumps and/or Rubella. Choose only one option. Copy Note: a 3rd dose of MMR vaccine may be advised during regional outbreaks of measles or mumps if original MMR vaccination was received in childhood. Attached Option1 Vaccine Date MMR Dose #1 MMR -2 doses of MMR vaccine MMR Dose #2 Option 2 Vaccine or Test Date Measles Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Measles Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Measles Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Mumps Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Mumps Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Mumps Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Serology Results Rubella Qualitative Positive Negative -1 dose of vaccine or Rubella Vaccine Titer Results: positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis – 1 dose of adult Tdap; if last Tdap is more than 10 years old, provide date of last Td or Tdap booster Tdap Vaccine (Adacel, Boostrix, etc) Td Vaccine or Tdap Vaccine booster (if more than 10 years since last Tdap) Varicella (Chicken Pox) - 2 doses of varicella vaccine or positive serology Varicella Vaccine #1 Serology Results Qualitative Varicella Vaccine #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Quantitative Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Influenza Vaccine --1 dose annually each fall Date Flu Vaccine © 2020 AAMC. -

Hepatitis B Vaccine – Frequently Asked Questions (Information from the CDC)

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form 2020 Hepatitis B Vaccine – Frequently Asked Questions (Information from the CDC) 1. What are the hepatitis B vaccines licensed for use in the United States? Three single-antigen vaccines and two combination vaccines are currently licensed in the United States. Single-antigen hepatitis B vaccines: • ENGERIX-B® • RECOMBIVAX HB® • HEPLISAV-B™ Combination vaccines: • PEDIARIX®: Combined hepatitis B, diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis (DTaP), and inactivated poliovirus (IPV) vaccine. Cannot be administered before age 6 weeks or after age 7 years. • TWINRIX®: Combined Hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccine. Recommended for people aged ≥18 years who are at increased risk for both HAV and HBV infections. 2. What are the recommended schedules for hepatitis B vaccination? The vaccination schedule most often used for children and adults is three doses given at 0, 1, and 6 months. Alternate schedules have been approved for certain vaccines and/or populations. A new formulation, Heplisav-B (HepB-CpG), is approved to be given as two doses one month apart. 3. If there is an interruption between doses of hepatitis B vaccine, does the vaccine series need to be restarted? No. The series does not need to be restarted but the following should be considered: • If the vaccine series was interrupted after the first dose, the second dose should be administered as soon as possible. • The second and third doses should be separated by an interval of at least 8 weeks. • If only the third dose is delayed, it should be administered as soon as possible. 4. Is it harmful to administer an extra dose of hepatitis B vaccine or to repeat the entire vaccine series if documentation of the vaccination history is unavailable or the serology test is negative? No, administering extra doses of single-antigen hepatitis B vaccine is not harmful. -

Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule

Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule UNITED STATES for ages 19 years or older 2021 Recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices How to use the adult immunization schedule (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip) and approved by the Centers for Disease Determine recommended Assess need for additional Review vaccine types, Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov), American College of Physicians 1 vaccinations by age 2 recommended vaccinations 3 frequencies, and intervals (www.acponline.org), American Academy of Family Physicians (www.aafp. (Table 1) by medical condition and and considerations for org), American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (www.acog.org), other indications (Table 2) special situations (Notes) American College of Nurse-Midwives (www.midwife.org), and American Academy of Physician Assistants (www.aapa.org). Vaccines in the Adult Immunization Schedule* Report y Vaccines Abbreviations Trade names Suspected cases of reportable vaccine-preventable diseases or outbreaks to the local or state health department Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine Hib ActHIB® y Clinically significant postvaccination reactions to the Vaccine Adverse Event Hiberix® Reporting System at www.vaers.hhs.gov or 800-822-7967 PedvaxHIB® Hepatitis A vaccine HepA Havrix® Injury claims Vaqta® All vaccines included in the adult immunization schedule except pneumococcal 23-valent polysaccharide (PPSV23) and zoster (RZV) vaccines are covered by the Hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccine HepA-HepB Twinrix® Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. Information on how to file a vaccine injury Hepatitis B vaccine HepB Engerix-B® claim is available at www.hrsa.gov/vaccinecompensation. Recombivax HB® Heplisav-B® Questions or comments Contact www.cdc.gov/cdc-info or 800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636), in English or Human papillomavirus vaccine HPV Gardasil 9® Spanish, 8 a.m.–8 p.m. -

Techniques and Talking Points to Address Vaccine Hesitancy

Techniques and Talking Points to Address Vaccine Hesitancy Kristin Oliver, MD, MHS Assistant Professor Department of Environmental Medicine & Public Health Department of Pediatrics Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai I have no financial disclosures Worldwide prevent 2-3 million deaths every year. In US prevent 42,000 deaths per birth cohort. Discuss reasons for vaccine hesitancy. Answer the most common questions Objectives and concerns surrounding vaccines. Apply Motivational Interviewing (MI) strategies to address vaccine hesitancy. Most Parents Vaccinate Percent children age 24 months who received vaccinations, 2017 1.3% Percent Unvaccinated 1.4 1.3% 1.2 1 0.8 0.9% 0.6 0.4 0.2 98.7% 0 2011 2015 Percent Unvaccinated Unvaccinated Vaccinated Data source: Vaccination Coverage Among Children Aged 19–35 Months — United States, 2017. MMWR. v. 67, no. 40 ≥ 1 MMR Vaccination Coverage Among Children 19-35 Months 2017 Content source: National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/childvaxview/data- reports/mmr/trend/index.html Heat Map of Select County Non-Medical Exemption Rates, 2016-2017 Olive JK, Hotez PJ, Damania A, Nolan MS (2018) The state of the antivaccine movement in the United States: A focused examination of nonmedical exemptions in states and counties. PLOS Medicine 15(6): e1002578. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002578 https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002578 Parents Differ in Attitudes Towards Vaccination Data: Gust et al. Am J Behav. 2005;29(1): 81-92. Figure: Sanofi Pasteur 9/15 MKT30043 Will too many vaccines overwhelm the immune system? Common Questions From Vaccine Isn’t it better to space vaccines out? Hesitant Families Does MMR vaccine cause autism? (and their friends and neighbors and Are there harmful ingredients in strangers at vaccines? cocktail parties) Isn’t it better to get the natural infection? Source: Immunization Action Coalition. -

2021-22 School Year New York State Immunization Requirements for School Entrance/Attendance1

2021-22 School Year New York State Immunization Requirements for School Entrance/Attendance1 NOTES: Children in a prekindergarten setting should be age-appropriately immunized. The number of doses depends on the schedule recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Intervals between doses of vaccine should be in accordance with the ACIP-recommended immunization schedule for persons 0 through 18 years of age. Doses received before the minimum age or intervals are not valid and do not count toward the number of doses listed below. See footnotes for specific information foreach vaccine. Children who are enrolling in grade-less classes should meet the immunization requirements of the grades for which they are age equivalent. Dose requirements MUST be read with the footnotes of this schedule Prekindergarten Kindergarten and Grades Grades Grade Vaccines (Day Care, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 12 Head Start, and 11 Nursery or Pre-k) Diphtheria and Tetanus 5 doses toxoid-containing vaccine or 4 doses and Pertussis vaccine 4 doses if the 4th dose was received 3 doses (DTaP/DTP/Tdap/Td)2 at 4 years or older or 3 doses if 7 years or older and the series was started at 1 year or older Tetanus and Diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine Not applicable 1 dose and Pertussis vaccine adolescent booster (Tdap)3 Polio vaccine (IPV/OPV)4 4 doses 3 doses or 3 doses if the 3rd dose was received at 4 years or older Measles, Mumps and 1 dose 2 doses Rubella vaccine (MMR)5 Hepatitis B vaccine6 3 doses 3 doses or 2 doses of adult hepatitis B vaccine (Recombivax) for children who received the doses at least 4 months apart between the ages of 11 through 15 years Varicella (Chickenpox) 1 dose 2 doses vaccine7 Meningococcal conjugate Grades 2 doses vaccine (MenACWY)8 7, 8, 9, 10 or 1 dose Not applicable and 11: if the dose 1 dose was received at 16 years or older Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine 1 to 4 doses Not applicable (Hib)9 Pneumococcal Conjugate 1 to 4 doses Not applicable vaccine (PCV)10 Department of Health 1. -

Improving Vaccination Coverage Fact Sheet

Improving Vaccination Coverage Fact Sheet Improving Vaccination Coverage for Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Public confidence in immunization is critical to sustaining and increasing vaccination coverage rates and preventing outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs). There is some evidence suggesting vaccination requirements that have broad reach, limited exemption criteria, and strong enforcement may help promote higher rates of vaccination coverage along with complementary actions such as monitoring VPD cases, vaccination coverage, and exemption rates; and also reporting on recent VPD outbreaks. Importation of measles into the U.S. emphasizes the importance of sustaining and increasing vaccination coverage rates to prevent outbreaks of VPDs. Measles is a highly-contagious respiratory disease caused by a virus. It spreads through the air through coughing and sneezing. Measles starts with a fever, runny nose, cough, red eyes, and sore throat, and is followed by a rash that spreads all over the body. About three out of 10 people who get measles will develop one or more complications including pneumonia, ear infections, or diarrhea. Complications are more common in children younger than age 5 and adults. Measles cases and outbreaks still occur in countries in Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. Worldwide, about 20 million people get measles each year; about 146,000 die. Each year, unvaccinated people get infected while in other countries and bring the disease into the United States and spread it to others. Since 2000, when measles was declared eliminated from the U.S., the annual number of people reported to have measles ranged from a low of 37 people in 2004 to a high of 668 people in 2014. -

The GAVI Alliance

GLOBAL PROGRAM REVIEW The GAVI Alliance Global Program Review The World Bank’s Partnership with the GAVI Alliance Main Report and Annexes Contents ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................................. V ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................................ XI PROGRAM AT A GLANCE: THE GAVI ALLIANCE ............................................................................ XII KEY BANK STAFF RESPONSIBLE DURING PERIOD UNDER REVIEW ........................................ XIV GLOSSARY ......................................................................................................................................... XV OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................................ XVII GAVI ALLIANCE MANAGEMENT RESPONSE .............................................................................. XXV WORLD BANK GROUP MANAGEMENT RESPONSE ................................................................... XXIX CHAIRPERSON’S SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... XXXI 1. THE WORLD BANK-GAVI PARTNERSHIP AND THE PURPOSE OF THE REVIEW ...................... 1 Evolution of GAVI ..................................................................................................................................................... -

The Thimerosal Controversy

The Thimerosal Controversy Aimee Sutherland, VRG Research Assistant April 2013 Background In the early 1920s, a major public health concern was vaccine contamination with bacteria and other germs, which could result in the death of children receiving the vaccines from tainted vials. In the book “The Hazards of Immunization”, Sir Graham S. Wilson depicts an occurrence of contamination that happened in Australia in 1928 in which twelve out of twenty-one children died after receiving the vaccine for diphtheria due to multiple staphylococcal abscesses and toxemia (FDA). This incident spurred the development of preservatives for multi-dose vials of vaccine. In 1928, Eli Lilly was the first pharmaceutical company to introduce thimerosal, an organomercury compound that is approximately 50% mercury by weight, as a preservative that would thwart microbial growth (FDA). After its introduction as a germocide, thimerosal was often challenged for its efficacy rather than its safety. The American Medical Association (AMA) published an article that questioned the effectiveness of the organomercury compounds over the inorganic mercury ones (Baker, 245). In 1938 manufacturers were required to submit safety-testing information to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Although preservatives had already been incorporated into many vaccines, it was not until 1968 that preservatives were required for multi-dose vials in the United States Code of Federal Regulations (FDA). In 1970s the American population, increasingly concerned about environmental contamination with heavy metals, began to have reservations about the safety of organomercury and the controversy regarding thimerosal ensued after. The Controversy In 1990s, the use of thimerosal as a preservative became controversial and was targeted as a possible cause of autism because of its mercury content. -

COVID-19: Mechanisms of Vaccination and Immunity

Review COVID-19: Mechanisms of Vaccination and Immunity Daniel E. Speiser 1,* and Martin F. Bachmann 2,3,4,* 1 Department of Oncology, University Hospital and University of Lausanne, 1066 Lausanne, Switzerland 2 International Immunology Centre, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei 230036, China 3 Department of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergology, Inselspital, University of Bern, 3010 Bern, Switzerland 4 Department of BioMedical Research, University of Bern, 3008 Bern, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.E.S.); [email protected] (M.F.B.) Received: 2 July 2020; Accepted: 20 July 2020; Published: 22 July 2020 Abstract: Vaccines are needed to protect from SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing COVID-19. Vaccines that induce large quantities of high affinity virus-neutralizing antibodies may optimally prevent infection and avoid unfavorable effects. Vaccination trials require precise clinical management, complemented with detailed evaluation of safety and immune responses. Here, we review the pros and cons of available vaccine platforms and options to accelerate vaccine development towards the safe immunization of the world’s population against SARS-CoV-2. Favorable vaccines, used in well-designed vaccination strategies, may be critical for limiting harm and promoting trust and a long-term return to normal public life and economy. Keywords: SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19; nucleic acid tests; serology; vaccination; immunity 1. Introduction The COVID-19 pandemic holds great challenges for which the world is only partially prepared [1]. SARS-CoV-2 combines serious pathogenicity with high infectivity. The latter is enhanced by the fact that asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic individuals can transmit the virus, in contrast to SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV, which were transmitted by symptomatic patients and could be contained more efficiently [2,3].