Global Immunization and Gavi Five Priorities for the Next Five Years Center for Global Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gavi's Vaccine Investment Strategy

Gavi’s Vaccine Investment Strategy Deepali Patel THIRD WHO CONSULTATION ON GLOBAL ACTION PLAN FOR INFLUENZA VACCINES (GAP III) Geneva, Switzerland, 15-16 November 2016 www.gavi.org Vaccine Investment Strategy (VIS) Evidence-based approach to identifying new vaccine priorities for Gavi support Strategic investment Conducted every 5 years decision-making (rather than first-come- first-serve) Transparent methodology Consultations and Predictability of Gavi independent expert advice programmes for long- term planning by Analytical review of governments, industry evidence and modelling and donors 2 VIS is aligned with Gavi’s strategic cycle and replenishment 2011-2015 Strategic 2016-2020 Strategic 2021-2025 period period 2008 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 2025 RTS,S pilot funding decision VIS #1 VIS #2 VIS #3 MenA, YF mass campaigns, JE, HPV Cholera stockpile, Mid 2017 : vaccine ‘long list’ Rubella, Rabies/cholera studies, Oct 2017 : methodology Typhoid Malaria – deferred Jun 2018 : vaccine shortlist conjugate Dec 2018 : investment decisions 3 VIS process Develop Collect data Develop in-depth methodology and Apply decision investment decision framework for cases for framework with comparative shortlisted evaluation analysis vaccines criteria Phase I Narrow long list Phase II Recommend for Identify long list to higher priority Gavi Board of vaccines vaccines approval of selected vaccines Stakeholder consultations and independent expert review 4 Evaluation criteria (VIS #2 – 2013) Additional Health Implementation -

CLINICAL TRIALS Safety and Immunogenicity of a Nicotine Conjugate Vaccine in Current Smokers

CLINICAL TRIALS Safety and immunogenicity of a nicotine conjugate vaccine in current smokers Immunotherapy is a novel potential treatment for nicotine addiction. The aim of this study was to assess the safety and immunogenicity of a nicotine conjugate vaccine, NicVAX, and its effects on smoking behavior. were recruited for a noncessation treatment study and assigned to 1 of 3 doses of the (68 ؍ Smokers (N nicotine vaccine (50, 100, or 200 g) or placebo. They were injected on days 0, 28, 56, and 182 and monitored for a period of 38 weeks. Results showed that the nicotine vaccine was safe and well tolerated. Vaccine immunogenicity was dose-related (P < .001), with the highest dose eliciting antibody concentrations within the anticipated range of efficacy. There was no evidence of compensatory smoking or precipitation of nicotine withdrawal with the nicotine vaccine. The 30-day abstinence rate was significantly different across with the highest rate of abstinence occurring with 200 g. The nicotine vaccine appears ,(02. ؍ the 4 doses (P to be a promising medication for tobacco dependence. (Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005;78:456-67.) Dorothy K. Hatsukami, PhD, Stephen Rennard, MD, Douglas Jorenby, PhD, Michael Fiore, MD, MPH, Joseph Koopmeiners, Arjen de Vos, MD, PhD, Gary Horwith, MD, and Paul R. Pentel, MD Minneapolis, Minn, Omaha, Neb, Madison, Wis, and Rockville, Md Surveys show that, although about 41% of smokers apy, is about 25% on average.2 Moreover, these per- make a quit attempt each year, less than 5% of smokers centages most likely exaggerate the efficacy of are successful at remaining abstinent for 3 months to a intervention because these trials are typically composed year.1 Smokers seeking available behavioral and phar- of subjects who are highly motivated to quit and who macologic therapies can enhance successful quit rates are free of complicating diagnoses such as depression 2 by 2- to 3-fold over control conditions. -

Vaccination Certificate Information Version: 21 July 2021

معلومات عن شهادة التطعيم، بالعربية 中文疫苗接种凭证信息 Informations sur le certificat de vaccination en FRANÇAIS Информация о сертификате вакцинации на РУССКОМ ЯЗЫКЕ Información sobre el Certificado de Vacunación en ESPAÑOL UN SYSTEM-WIDE COVID-19 VACCINATION PROGRAMME VACCINATION CERTIFICATE INFORMATION VERSION: 21 JULY 2021 ABOUT THE UN SYSTEM-WIDE COVID-19 VACCINATION PROGRAMME The UN is committed to ensuring the protection of its personnel. Tasked by the Secretary-General, the Department of Operational Support (DOS) is leading a coordinated, UN-system-wide effort to ensure the availability of vaccine to UN personnel, their dependents and implementing partners. The roll-out of the UN System-wide COVID-19 Vaccination Programme (the “Programme”) for UN personnel will provide a significant boost to the ability of personnel to stay and deliver on the Organization's mandates, to support beneficiaries in the communities they serve, and to contribute to our on-going work to recover better together from the pandemic. Information about the Programme is available at: https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/vaccination ABOUT THE VACCINATION CERTIFICATE Upon administration of the requisite vaccine dosage, a certificate of vaccination is generated through the Programme’s registration platform (the “Platform”). The certificate generated by the Platform uses a standardized format, similar to the one used by the WHO in its “International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis” (Yellow) vaccination booklet. Note: This certificate may not dispense with travel restrictions put in place by the country(ies) of destination. As the nature of the pandemic continues to rapidly evolve, it is highly advisable to check the latest travel regulations. -

Global Dynamics of a Vaccination Model for Infectious Diseases with Asymptomatic Carriers

MATHEMATICAL BIOSCIENCES doi:10.3934/mbe.2016019 AND ENGINEERING Volume 13, Number 4, August 2016 pp. 813{840 GLOBAL DYNAMICS OF A VACCINATION MODEL FOR INFECTIOUS DISEASES WITH ASYMPTOMATIC CARRIERS Martin Luther Mann Manyombe1;2 and Joseph Mbang1;2 Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science University of Yaounde 1, P.O. Box 812 Yaounde, Cameroon 1;2;3; Jean Lubuma and Berge Tsanou ∗ Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa (Communicated by Abba Gumel) Abstract. In this paper, an epidemic model is investigated for infectious dis- eases that can be transmitted through both the infectious individuals and the asymptomatic carriers (i.e., infected individuals who are contagious but do not show any disease symptoms). We propose a dose-structured vaccination model with multiple transmission pathways. Based on the range of the explic- itly computed basic reproduction number, we prove the global stability of the disease-free when this threshold number is less or equal to the unity. Moreover, whenever it is greater than one, the existence of the unique endemic equilibrium is shown and its global stability is established for the case where the changes of displaying the disease symptoms are independent of the vulnerable classes. Further, the model is shown to exhibit a transcritical bifurcation with the unit basic reproduction number being the bifurcation parameter. The impacts of the asymptomatic carriers and the effectiveness of vaccination on the disease transmission are discussed through through the local and the global sensitivity analyses of the basic reproduction number. Finally, a case study of hepatitis B virus disease (HBV) is considered, with the numerical simulations presented to support the analytical results. -

Yellow Fever 2016

Resident / Humanitarian Coordinator Report on the use of CERF funds RESIDENT / HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS ANGOLA RAPID RESPONSE YELLOW FEVER 2016 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR Pier Paolo Balladelli REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. Review agreed on 02/09/2016 and 07/09/2016. b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team and by cluster/sector coordinators as outlined in the guidelines. YES NO c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders as recommended in the guidelines (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant government counterparts)? YES NO Final version shared with UNICEF and UNDP, although this initiative was mainly implemented by WHO 2 I. HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT TABLE 1: EMERGENCY ALLOCATION OVERVIEW (US$) Total amount required for the humanitarian response: Source Amount CERF 3,000,000 Breakdown of total response COUNTRY-BASED POOL FUND (if applicable) 4,508,559 funding received by source OTHER (bilateral/multilateral) TOTAL 10,473,618 *The total amount does not match because this was considered an underfunded emergency. TABLE 2: CERF EMERGENCY FUNDING BY ALLOCATION AND PROJECT (US$) Allocation 1 – date of official submission: 06/04/2016- 05/10/2016 Agency Project code Cluster/Sector -

Hanna Nohynek @Hnohynek

Biosketch Hanna Nohynek @hnohynek Hanna Nohynek is Chief Physician and Deputy Head of the Infectious Diseases Control and Vaccines Unit of the Department of Health Security at the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. She serves as secretary of the Finnish NITAG (KRAR), and leads the subgroup on Strategic development of the influenza vaccination programme and the subgroup on the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination strategy. She practices clinical medicine at a travel health clinic in Aava, Helsinki. She was instrumental in designing the first THL (KTL) health advisory for refugees and asylum seekers in Finland, studying the narcolepsy signal post pandemic vaccination, designing the introduction of the HPV vaccine to the national immunization programme, and the introduction of the live attenuated influenza vaccine for children. Her present research interests are register-based vaccine impact studies, evidence based policy/decision making, vaccine safety, hesitancy, SARS-CoV-2, RSV, influenza and pneumococcus. She coordinates the work packages on field studies and communication for IMI DRIVE on brand specific influenza vaccine effectiveness (www.drive-eu.org). She has authored more than 130 original articles (including the first scientific report on the association between pandemic influenza vaccination and narcolepsy), and she teaches, giving over 30 invited lectures annually and guiding elective, graduate and PhD students (presently Raija Auvinen and Idil Hussein). She belongs to the external faculty of the University of Tampere MSc course on Global Health. She has served on expert committees evaluating HBV, PCV and rota virus vaccines in Finland, and as an advisor to the EU, IMI, IVI, WHO, GAVI, SIDA/SRC, and the Finnish MOFA. -

UNEP Mercury Treaty Protects Access to Thiomersal-Containing Vaccines

UNEP mercury treaty protects access to thiomersal-containing vaccines United Nations Environment Program has developed a treaty on mercury in an effort to protect human health and the environment by limiting mercury releases. In the course of the negotiations, a proposal was made to restrict vaccines that contain the preservative thiomersal under a section of the treaty that prohibits trade of mercury-added products. The implications of restricting thiomersal, an ethyl mercury-containing preservative, would be significant. According to SAGE, “Thiomersal-containing vaccines [are] safe, essential, and irreplaceable components of immunization programs, especially in developing countries, and…removal of these products would disproportionately jeopardize the health and lives of the most disadvantaged children worldwide.” The treaty annex that describes prohibited products specifically excludes “vaccines containing thiomersal as preservatives” under a short list of products the authors intended to emphasize were to be protected. Protecting access to vaccines came as the result of a strong partnership between WHO, UNICEF, GAVI, and civil society advocates and experts around the world to educate country delegates, who predominantly came from ministries of environment. This was also a wonderful partnership with animal health experts, who similarly rely on thiomersal for veterinary vaccines. By facilitating communication between ministries of health and ministries of environment, strong statements are made by delegates about the essential role of thiomersal-containing vaccines in protecting human health. PATH will be collecting and disseminating additional information about how the community came together around this issue and lessons learned in the coming months. . -

Immunization Policies and Procedures Manual

Immunization Policies and Procedures Manual Louisiana Department of Health Office of Public Health Immunization Program Revised September 2017 i Center for Community and Preventive Health Bureau of Infectious Diseases Immunization Program TABLE OF CONTENTS I. POLICY AND GENERAL CLINIC POLICY ............................................................................................................................. 1 PURPOSE ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 POLICY ON CLINIC SCHEDULING ............................................................................................................................................ 2 POLICY ON PUBLICITY FOR IMMUNIZATION ACTIVITIES .............................................................................................. 4 POLICY ON EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES (HEALTH EDUCATION IN IMMUNIZATION CLINICS) .......................... 5 POLICY ON CHECKING IMMUNIZATION STATUS OF ALL CHILDREN RECEIVING SERVICES THROUGH THE HEALTH DEPARTMENT ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 POLICY ON MAXIMIZING TIME SPENT WITH PARENTS DURING IMMUNIZATION CLINICS ............................... 7 POLICY ON ASSISTANCE TO FOREIGN TRAVELERS .......................................................................................................... 9 II. POLICY -

UNICEF Immunization Roadmap 2018-2030

UNICEF IMMUNIZATION ROADMAP 2018–2030 Cover: ©UNICEF/UN065768/Khouder Al-Issa A health worker vaccinates 3-year-old Rahaf in Tareek Albab neighborhood in the eastern part of Aleppo city. UNICEF IMMUNIZATION ROADMAP 2018–2030 Photograph credits: Pages vi-vii: © Shutterstock/thi Page 5: © UNICEF/UN060913/Al-Issa Page 6: © UNICEF/UNI41364/Estey Page 10: © UNICEF/UN061432/Dejongh Page 14: © UNICEF/UNI76541/Holmes Page 18: © UNICEF/UN0125829/Sharma Page 24: © UNICEF/UN059884/Zar Mon Page 26: © UNICEF/UN065770/Al-Issa Page 33: © UNICEF/UN0143438/Alhariri Page 34: © UNICEF/UNI45693/Estey Page 38: © UNICEF/UNI77040/Holmes Page 40: © UNICEF/UN0125861/Sharma Page 44: © UNICEF/UNI41211/Holmes © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), September 2018 Permission is required to reproduce any part of this publication. Permission will be freely granted to educational or non-profit organizations. Please contact: Health Section, Immunization Team UNICEF 3 United Nations Plaza New York, NY 100017 Contents Abbreviations viii Executive summary 1 1. Introduction 7 1.1 Background 7 1.2 Developing the Roadmap 9 2. Key considerations informing the UNICEF Immunization Roadmap 11 2.1 Key drivers of immunization through 2030 11 2.2 Evolving immunization partnerships 15 2.3 UNICEF’s comparative advantage in immunization 16 3. What is new in this Roadmap? 19 3.1 Immunization coverage as a tracer indicator of child equity 19 3.2 Key areas of work 21 4. Roadmap programming framework 27 4.1 Vision and impact statements 27 4.2 Programming principles 27 4.3 Context-driven responses 27 4.4 Objectives and priorities 29 4.5 Populations and platforms 32 4.6 Country-level immunization strategies 32 5. -

Vaccine Hesitancy

WHY CHILDREN WORKSHOP ON IMMUNIZATIONS ARE NOT VACCINATED? VACCINE HESITANCY José Esparza MD, PhD - Adjunct Professor, Institute of Human Virology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA - Robert Koch Fellow, Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany - Senior Advisor, Global Virus Network, Baltimore, MD, USA. Formerly: - Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA, USA - World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland The value of vaccination “The impact of vaccination on the health of the world’s people is hard to exaggerate. With the exception of safe water, no other modality has had such a major effect on mortality reduction and population growth” Stanley Plotkin (2013) VACCINES VAILABLE TO PROTECT AGAINST MORE DISEASES (US) BASIC VACCINES RECOMMENDED BY WHO For all: BCG, hepatitis B, polio, DTP, Hib, Pneumococcal (conjugated), rotavirus, measles, rubella, HPV. For certain regions: Japanese encephalitis, yellow fever, tick-borne encephalitis. For some high-risk populations: typhoid, cholera, meningococcal, hepatitis A, rabies. For certain immunization programs: mumps, influenza Vaccines save millions of lives annually, worldwide WHAT THE WORLD HAS ACHIEVED: 40 YEARS OF INCREASING REACH OF BASIC VACCINES “Bill Gates Chart” 17 M GAVI 5.6 M 4.2 M Today (ca 2015): <5% of children in GAVI countries fully immunised with the 11 WHO- recommended vaccines Seth Berkley (GAVI) The goal: 50% of children in GAVI countries fully immunised by 2020 Seth Berkley (GAVI) The current world immunization efforts are achieving: • Equity between high and low-income countries • Bringing the power of vaccines to even the world’s poorest countries • Reducing morbidity and mortality in developing countries • Eliminating and eradicating disease WHY CHILDREN ARE NOT VACCINATED? •Vaccines are not available •Deficient health care systems •Poverty •Vaccine hesitancy (reticencia a la vacunacion) VACCINE HESITANCE: WHO DEFINITION “Vaccine hesitancy refers to delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services. -

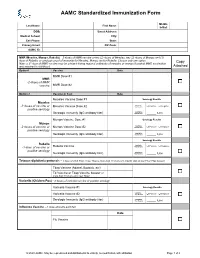

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form Middle Last Name: First Name: Initial: DOB: Street Address: Medical School: City: Cell Phone: State: Primary Email: ZIP Code: AAMC ID: MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) – 2 doses of MMR vaccine or two (2) doses of Measles, two (2) doses of Mumps and (1) dose of Rubella; or serologic proof of immunity for Measles, Mumps and/or Rubella. Choose only one option. Copy Note: a 3rd dose of MMR vaccine may be advised during regional outbreaks of measles or mumps if original MMR vaccination was received in childhood. Attached Option1 Vaccine Date MMR Dose #1 MMR -2 doses of MMR vaccine MMR Dose #2 Option 2 Vaccine or Test Date Measles Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Measles Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Measles Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Mumps Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Mumps Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Mumps Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Serology Results Rubella Qualitative Positive Negative -1 dose of vaccine or Rubella Vaccine Titer Results: positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis – 1 dose of adult Tdap; if last Tdap is more than 10 years old, provide date of last Td or Tdap booster Tdap Vaccine (Adacel, Boostrix, etc) Td Vaccine or Tdap Vaccine booster (if more than 10 years since last Tdap) Varicella (Chicken Pox) - 2 doses of varicella vaccine or positive serology Varicella Vaccine #1 Serology Results Qualitative Varicella Vaccine #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Quantitative Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Influenza Vaccine --1 dose annually each fall Date Flu Vaccine © 2020 AAMC. -

Hepatitis B Vaccine – Frequently Asked Questions (Information from the CDC)

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form 2020 Hepatitis B Vaccine – Frequently Asked Questions (Information from the CDC) 1. What are the hepatitis B vaccines licensed for use in the United States? Three single-antigen vaccines and two combination vaccines are currently licensed in the United States. Single-antigen hepatitis B vaccines: • ENGERIX-B® • RECOMBIVAX HB® • HEPLISAV-B™ Combination vaccines: • PEDIARIX®: Combined hepatitis B, diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis (DTaP), and inactivated poliovirus (IPV) vaccine. Cannot be administered before age 6 weeks or after age 7 years. • TWINRIX®: Combined Hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccine. Recommended for people aged ≥18 years who are at increased risk for both HAV and HBV infections. 2. What are the recommended schedules for hepatitis B vaccination? The vaccination schedule most often used for children and adults is three doses given at 0, 1, and 6 months. Alternate schedules have been approved for certain vaccines and/or populations. A new formulation, Heplisav-B (HepB-CpG), is approved to be given as two doses one month apart. 3. If there is an interruption between doses of hepatitis B vaccine, does the vaccine series need to be restarted? No. The series does not need to be restarted but the following should be considered: • If the vaccine series was interrupted after the first dose, the second dose should be administered as soon as possible. • The second and third doses should be separated by an interval of at least 8 weeks. • If only the third dose is delayed, it should be administered as soon as possible. 4. Is it harmful to administer an extra dose of hepatitis B vaccine or to repeat the entire vaccine series if documentation of the vaccination history is unavailable or the serology test is negative? No, administering extra doses of single-antigen hepatitis B vaccine is not harmful.