International Regime Theory: ASEAN As a Case Study Dan Patrick Hercl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

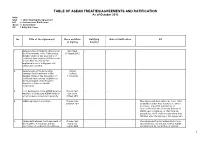

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Australia and the Origins of ASEAN (1967–1975)

1 Australia and the origins of ASEAN (1967–1975) The origins of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and of Australia’s relations with it are bound up in the period of the Cold War in East Asia from the late 1940s, and the serious internal and inter-state conflicts that developed in Southeast Asia in the 1950s and early 1960s. Vietnam and Laos were engulfed in internal wars with external involvement, and conflict ultimately spread to Cambodia. Further conflicts revolved around Indonesia’s unstable internal political order and its opposition to Britain’s efforts to secure the positions of its colonial territories in the region by fostering a federation that could include Malaya, Singapore and the states of North Borneo. The Federation of Malaysia was inaugurated in September 1963, but Singapore was forced to depart in August 1965 and became a separate state. ASEAN was established in August 1967 in an effort to ameliorate the serious tensions among the states that formed it, and to make a contribution towards a more stable regional environment. Australia was intensely interested in all these developments. To discuss these issues, this chapter covers in turn the background to the emergence of interest in regional cooperation in Southeast Asia after the Second World War, the period of Indonesia’s Konfrontasi of Malaysia, the formation of ASEAN and the inauguration of multilateral relations with ASEAN in 1974 by Gough Whitlam’s government, and Australia’s early interactions with ASEAN in the period 1974‒75. 7 ENGAGING THE NEIGHBOURS The Cold War era and early approaches towards regional cooperation The conception of ‘Southeast Asia’ as a distinct region in which states might wish to engage in regional cooperation emerged in an environment of international conflict and the end of the era of Western colonialism.1 Extensive communication and interactions developed in the pre-colonial era, but these were disrupted thoroughly by the arrival of Western powers. -

The IMF and the World Bank in an Evolving World

3 The IMF and the World Bank in an Evolving World This session fea tured two speakers from major countries who have played ac tive and important roles in their countries for many years. The first speaker was Manmohan Singh, the Finance Minister of India and one of the chief archi tects of lndia's recent economic reform program. He was followed by C. Fred Bergsten, the founder and Director of the Institute for International Economics and a fo nner Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Tr easury Department. After they addressed the global issues affecting the Bretton Woods institutions from their unique perspectives, the Chairman of the session-lıımberto Dini, Minister of the Tr easury of Italy-offered an overview and synthesis of the suggestions presented. The speakers then responded to a number of questions and com ments raised by other participants. Manmohan Singh When I was invited to speak at this conference, I accepted with great pleasure. Fiftieth anniversaries are festive occasions when old friends gather to relive pleasant memories, to rejoice and felicitate. I have been privileged, in various capacities in the Government of India, to dea! with the Bretton Woods institutions for almost half of the 50 years we are commemorating today. I have innumerable pleasant memories and old friends associated with these institutions and it is therefore a partic ular pleasure to be part of this celebration. Twoscore and ten years is not a very long time for historians, but it is time enough to reflect on the achievements of institutions and draw new blueprints for the future. -

ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: from Cold War to Conditionality

ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: From Cold War to Conditionality Lee Jones Abstract Despite their other theoretical differences, virtually all scholars of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) agree that the organisation’s members share an almost religious commitment to the norm of non-intervention. This article disrupts this consensus, arguing that ASEAN repeatedly intervened in Cambodia’s internal political conflicts from 1979-1999, often with powerful and destructive effects. ASEAN’s role in maintaining Khmer Rouge occupancy of Cambodia’s UN seat, constructing a new coalition government-in-exile, manipulating Khmer refugee camps and informing the content of the Cambodian peace process will be explored, before turning to the ‘creeping conditionality’ for ASEAN membership imposed after the 1997 ‘coup’ in Phnom Penh. The article argues for an analysis recognising the political nature of intervention, and seeks to explain both the creation of non- intervention norms, and specific violations of them, as attempts by ASEAN elites to maintain their own illiberal, capitalist regimes against domestic and international political threats. Keywords ASEAN, Cambodia, Intervention, Norms, Non-Interference, Sovereignty Contact Information Lee Jones is a doctoral candidate in International Relations at Nuffield College, Oxford, OX1 1NF, UK. His research focuses on ASEAN and intervention in Cambodia, East Timor, and Burma. Comments are welcomed. Email: [email protected]. Tel/Fax: (+44) (0)1865 28890. ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: -

The Role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Democracy Support

The role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in post-conflict reconstruction and democracy support www.idea.int THE ROLE OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS IN POST- CONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION AND DEMOCRACY SUPPORT Julio S. Amador III and Joycee A. Teodoro © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance International IDEA Strömsborg SE-103 34, STOCKHOLM SWEDEN Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected], website: www.idea.int The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit thepublication as well as to remix and adapt it provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence see: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-sa/3.0/>. International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Graphic design by Turbo Design CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 4 2. ASEAN’S INSTITUTIONAL MANDATES ............................................................... 5 3. CONFLICT IN SOUTH-EAST ASIA AND THE ROLE OF ASEAN ...... 7 4. ADOPTING A POST-CONFLICT ROLE FOR -

International Governmental Organization Knowledge Management for Multilateral Trade Lawmaking Michael P

American University International Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 6 Article 6 2000 International Governmental Organization Knowledge Management for Multilateral Trade Lawmaking Michael P. Ryan W. Christopher Lenhardt Katsuya Tamai Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Ryan, Michael P., et al. "International Governmental Organization Knowledge Management for Multilateral Trade Lawmaking." American University International Law Review 15, no. 6 (2000): 1347-1378. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERNATIONAL GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATION KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT FOR MULTILATERAL TRADE LAWMAKING MICHAEL P. RYAN' W. CHRISTOPHER LENHARDT*° KATSUYA TAMAI INTRODUCTION ............................................ 1347 I. KNOWLEDGE AND THE FUNCTIONAL THEORY OF INTERNATIONAL GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATION ........................................ 1349 II. INTERNATIONAL GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS AS KNOWLEDGE MANAGERS .... 1356 III. ORGANIZATIONAL THEORY OF KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT ...................... 1361 IV. INTERNATIONAL GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATION KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT FOR MULTILATERAL -

Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015

Association of Southeast Asian Nations Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 One Vision, One Identity, One Community Association of Southeast Asian Nations Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. For inquiries, contact: Public Affairs Office The ASEAN Secretariat 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 Fax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail : [email protected] General information on ASEAN appears online at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org Catalogue-in-Publication Data Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, April 2009 352.1159 1. ASEAN – Summit – Blueprints 2. Political-Security – Economic – Socio-Cultural ISBN 978-602-8411-04-2 The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgement. Copyright ASEAN Secretariat 2009 All rights reserved ii Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Table of Contents Cha-am Hua Hin Declaration on the Roadmap for the ASEAN Community (2009-2015) ..........................01 ASEAN Political-Security Community Blueprint .........................................................................................05 ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint ....................................................................................................21 -

An Evolving ASEAN: Vision and Reality

Menon • Lee An Evolving ASEAN Vision and Reality The formation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in was originally driven by political and security concerns In the decades that followed ASEAN’s scope evolved to include an ambitious and progressive economic agenda In December the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) was formally launched Although AEC has enjoyed some notable successes the vision of economic integration has yet to be fully realized This publication reviews the evolution of ASEAN economic integration and assesses the major achievements It also examines the challenges that emerged during the past decade and provides recommendations on how to overcome them About the Asian Development Bank AN EVOLVING ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous inclusive resilient and sustainable Asia and the Pacifi c while sustaining its e orts to eradicate extreme poverty Established in it is owned by members— from the region Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue loans equity investments guarantees grants and technical assistance ASEAN: AN EVOLVING ASEAN VISION AND REALITY VISION Edited by Jayant Menon and Cassey Lee SEPTEMBER AND REALITY ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org 9 789292 616946 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK AN EVOLVING ASEAN VISION AND REALITY Edited by Jayant Menon and Cassey Lee SEPTEMBEr 2019 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2019 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. -

The Construction of International Regimes in East Asia: Coercion, Consensus and Collective Goods

THE CONSTRUCTION OF INTERNATIONAL REGIMES IN EAST ASIA: COERCION, CONSENSUS AND COLLECTIVE GOODS Mark Beeson A revised version of this paper was published in Sargeson, Sally (ed.), Collective Goods, Collective Futures in Asia, London: Routledge, 2002, pp 25-40. Abstract This paper employs theories of hegemony to explore the way the regional economic regime was reconstituted in the aftermath of the East Asian financial crisis of 1997. An important distinction is made here between realist and Gramscian notions of hegemony in the construction of international orders. I argue that while these perspectives are predicated upon very different assumptions about the way the world works, they both offer important insights about the development of the contemporary international political economy in East Asia. In the final section of the chapter I examine recent events in the region in more detail and consider their implications for the future of international relations more generally. It has become commonplace to observe that we live in an increasingly interconnected, not to say global era. While it is necessary to treat undifferentiated notions of ‘globalisation’ with some caution, international economic interaction in particular has clearly been accelerating. In such circumstances, the external environment within which international commerce occurs has become an increasingly important influence on both the activities of private economic actors and the more general domestic affairs of nations. The conduct of economic activity, both internationally -

Fifth ASEAN Summit: Introductory Note Sompong Sucharitkul Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected]

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Publications Faculty Scholarship 12-1995 Basic Documents - Fifth ASEAN Summit: Introductory Note Sompong Sucharitkul Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Sucharitkul, Sompong, "Basic Documents - Fifth ASEAN Summit: Introductory Note" (1995). Publications. Paper 540. http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs/540 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \ I BASIC DOCUMENTS lfiE'TH ASEAN SUMMIT BANGKOK, DECEMBER 14- 15, 1995 BANGKOK SUMMIT DECLARATION AND ANNEXES* [Done at Bangkok, December 15, 1995] + Cite as 35 ILM ..... (1996) + TREATY ON THE SOUTH-EAST ASIA NUCLEAR WEAPON-FREE ZONE .. WITH ANNEX AND PROTOCOL** [Done at Bangkok, December 15, 1995] + Cite as 35 ILM ..... (1996) + INTRODUCTORY NOTE BY SOMPONG SUCHARITKUL * Reproduced from the text supplied by the ASEAN Secretariat. The Introductory Note was prepared for International Legal Materials by Sompong Sucharitkul, O.C.L., Distinguished Professor of International and Comparative Law, Golden Gate University School of Law, First ASEAN Secretary-General (Thailand) 1967-1970. ** Reproduced from the text supplied by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand, with an Introductory Note by Sompong Sucharitkul. 1 ASEAN, The Association of South-East Asian Nations was established by the ASEAN Declaration of August 8, 1967 in Bangkok. -

ASEAN and the Environment Sompong Sucharitkul Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected]

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Publications Faculty Scholarship 1993 ASEAN and the Environment Sompong Sucharitkul Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation 3 Asian Yearbook of Int'l. L. (1993) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Asian Yearbook of International Law published under the auspices of the Foundation for the Development of International Law in Asia (DILA) General Editors Ko Swan Sik- M.C.W. Pinto - J.J.C. Syatauw VOLUME 3 1993 ASEAN AND THE ENVIRONMENT By SOMPONG SUCHARITKUL ASEAN AND THE ENVIRONlVIENT by SOMPONG SUCHARITKUL ASEAN AND THE ENVIRONMENT I. ASEAN AWARENESS OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT This is part of a series of studies devoted to the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), a dynamic regional organization for social, cultural and economic cooperation. 1 The ASEAN Society currently comprises six regional members : Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines and since January 7, 1984, Brunei Darussalam. 2 ASEAN tends to grow in membership and closer association with regional neighbors 3 and to expand in further intensified cooperation with its non-ASEAN, non-regional partners. 4 The object of this study is to examine some of ASEAN collective endeavors in the implementation of environmental protection within the ASEAN region and beyond. -

Europe As International Actor: Maximizing Nation-State Sovereignty by Laurent Goetschel* Fellow for European Studies Swiss Peace Foundation P.O

Program for the Study of Ge7ll'l£11ly and Europe Working Paper Series #6.3 Europe as International Actor: Maximizing Nation-State Sovereignty by Laurent Goetschel* Fellow for European Studies Swiss Peace Foundation P.O. Box CH . 3000 Berne 13 spfgoetsche [email protected] Tel 41 31 311 55 82 Fax 41 31 311 5583 Abstract The continually increasing literature on foreign- and security-policy dimensions of the European Union (EU) has provided no remedy for the widespread helplessness in gaining a purchase on Europe as an international actor. The basic hindrance to understanding this policy comes from an all-too-literal interpretation of the acronym involved: the CFSP is understood as a total or partial replacement of the nation-states' foreign and security policy. This article aims to point the way to a new understanding of the CFSP in which this policy is not based on the integration of nation state foreign and security policy. I suggest that the proper way to grasp the phenomenon of the CFSP is to describe it as an international regime whose goal is to administer links between economic integration and foreign- and security policy cooperation in the sense of maximizing the sovereignty of member states. This requires, on the one hand, the prevention of "spillovers" from the economic area that could interfere with the foreign- and security-policy indepen dence of member states. On the other hand, it demands applying the EU's economic potential to reinforce the foreign- and security-policy range of member states. Due to the logic of this policy, CFSP priorities and fields of ac tion differ profoundly from those of a national foreign and security policy.