CICP Working Paper No. 14: Cambodia's Engagement with ASEAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

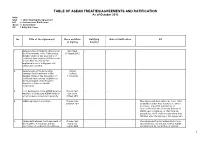

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

President Richard Nixon's Daily Diary, July 16-31, 1969

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest 7/30/1969 A 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest from Don- 7/30/1969 A Maung Airport, Bangkok 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/23/1969 A Appendix “B” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/24/1969 A Appendix “A” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/26/1969 A Appendix “B” 6 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/27/1969 A Appendix “A” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-3 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary July 16, 1969 – July 31, 1969 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) rnc.~IIJc.I'" rtIl."I'\ttU 1"'AUI'4'~ UAILJ UIAtU (See Travel Record for Travel Activity) ---- -~-------------------~--------------I PLACi-· DAY BEGA;'{ DATE (Mo., Day, Yr.) JULY 16, 1969 TIME DAY THE WHITE HOUSE - Washington, D. -

Agnew Assails U.S. Critics of Ewitary Aid to Thailand Va,T

Agnew Assails U.S. Critics Of e WitaryvA,t Aid to Thailand By Jack Foisie Loa Amities TIrries BANGKOK, Jan. 4—The Thal government, which has always decried American criti- cism of some aspects of Thai- American military coopera- tion, gained a new supporter today in Vice President Spiro Agnew. Meeting with Prime Minis- ter Thanom Kittikachorn for two hours today, Agnew de- clared: "Some people back home are so anxious to make friends of our enemies that they even seem ready to make enemies of our friends," The quote was approved for attribution to the Vice Presi- dent by American officials who sat in on the closed ses- sion- It was the second time on his Asian trip, now in its sec- ond week, that Agnew had re- newed his criticism of televi- sion and newspaper reporting, and of the people who do not wholly support American in- volvement in the Vietnam war. His comment could also apply to Sens. J. W. Fulbright (D-Ark.), Stuart Symington ID-Mo.) and Albert Gore (D- Tenn.), who have questioned the extent of US. commit- ments to Thailand. 0 t h e r Senators have opposed use of U.S. troops alland or Laos mout congressional approval. Both American and Thai ac- counts of the Thanom-Agnew talks said that most doubts had been dispelled about the Associated Prens "Nixon doctrine" of gradual The Agnews tour grounds of the Bangkok Grand Palace de-escalation of American po- litical and military presence• American policy, and no less- in Asia. They said Agnew declared the ening of U.S. -

Australia and the Origins of ASEAN (1967–1975)

1 Australia and the origins of ASEAN (1967–1975) The origins of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and of Australia’s relations with it are bound up in the period of the Cold War in East Asia from the late 1940s, and the serious internal and inter-state conflicts that developed in Southeast Asia in the 1950s and early 1960s. Vietnam and Laos were engulfed in internal wars with external involvement, and conflict ultimately spread to Cambodia. Further conflicts revolved around Indonesia’s unstable internal political order and its opposition to Britain’s efforts to secure the positions of its colonial territories in the region by fostering a federation that could include Malaya, Singapore and the states of North Borneo. The Federation of Malaysia was inaugurated in September 1963, but Singapore was forced to depart in August 1965 and became a separate state. ASEAN was established in August 1967 in an effort to ameliorate the serious tensions among the states that formed it, and to make a contribution towards a more stable regional environment. Australia was intensely interested in all these developments. To discuss these issues, this chapter covers in turn the background to the emergence of interest in regional cooperation in Southeast Asia after the Second World War, the period of Indonesia’s Konfrontasi of Malaysia, the formation of ASEAN and the inauguration of multilateral relations with ASEAN in 1974 by Gough Whitlam’s government, and Australia’s early interactions with ASEAN in the period 1974‒75. 7 ENGAGING THE NEIGHBOURS The Cold War era and early approaches towards regional cooperation The conception of ‘Southeast Asia’ as a distinct region in which states might wish to engage in regional cooperation emerged in an environment of international conflict and the end of the era of Western colonialism.1 Extensive communication and interactions developed in the pre-colonial era, but these were disrupted thoroughly by the arrival of Western powers. -

ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: from Cold War to Conditionality

ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: From Cold War to Conditionality Lee Jones Abstract Despite their other theoretical differences, virtually all scholars of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) agree that the organisation’s members share an almost religious commitment to the norm of non-intervention. This article disrupts this consensus, arguing that ASEAN repeatedly intervened in Cambodia’s internal political conflicts from 1979-1999, often with powerful and destructive effects. ASEAN’s role in maintaining Khmer Rouge occupancy of Cambodia’s UN seat, constructing a new coalition government-in-exile, manipulating Khmer refugee camps and informing the content of the Cambodian peace process will be explored, before turning to the ‘creeping conditionality’ for ASEAN membership imposed after the 1997 ‘coup’ in Phnom Penh. The article argues for an analysis recognising the political nature of intervention, and seeks to explain both the creation of non- intervention norms, and specific violations of them, as attempts by ASEAN elites to maintain their own illiberal, capitalist regimes against domestic and international political threats. Keywords ASEAN, Cambodia, Intervention, Norms, Non-Interference, Sovereignty Contact Information Lee Jones is a doctoral candidate in International Relations at Nuffield College, Oxford, OX1 1NF, UK. His research focuses on ASEAN and intervention in Cambodia, East Timor, and Burma. Comments are welcomed. Email: [email protected]. Tel/Fax: (+44) (0)1865 28890. ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: -

The Role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Democracy Support

The role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in post-conflict reconstruction and democracy support www.idea.int THE ROLE OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS IN POST- CONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION AND DEMOCRACY SUPPORT Julio S. Amador III and Joycee A. Teodoro © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance International IDEA Strömsborg SE-103 34, STOCKHOLM SWEDEN Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected], website: www.idea.int The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit thepublication as well as to remix and adapt it provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence see: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-sa/3.0/>. International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Graphic design by Turbo Design CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 4 2. ASEAN’S INSTITUTIONAL MANDATES ............................................................... 5 3. CONFLICT IN SOUTH-EAST ASIA AND THE ROLE OF ASEAN ...... 7 4. ADOPTING A POST-CONFLICT ROLE FOR -

Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015

Association of Southeast Asian Nations Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 One Vision, One Identity, One Community Association of Southeast Asian Nations Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. For inquiries, contact: Public Affairs Office The ASEAN Secretariat 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 Fax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail : [email protected] General information on ASEAN appears online at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org Catalogue-in-Publication Data Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, April 2009 352.1159 1. ASEAN – Summit – Blueprints 2. Political-Security – Economic – Socio-Cultural ISBN 978-602-8411-04-2 The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgement. Copyright ASEAN Secretariat 2009 All rights reserved ii Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Table of Contents Cha-am Hua Hin Declaration on the Roadmap for the ASEAN Community (2009-2015) ..........................01 ASEAN Political-Security Community Blueprint .........................................................................................05 ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint ....................................................................................................21 -

China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence: Principles and Foreign Policy

China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence: Principles and Foreign Policy Sophie Diamant Richardson Old Chatham, New York Bachelor of Arts, Oberlin College, 1992 Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Politics University of Virginia May, 2005 !, 11 !K::;=::: .' P I / j ;/"'" G 2 © Copyright by Sophie Diamant Richardson All Rights Reserved May 2005 3 ABSTRACT Most international relations scholarship concentrates exclusively on cooperation or aggression and dismisses non-conforming behavior as anomalous. Consequently, Chinese foreign policy towards small states is deemed either irrelevant or deviant. Yet an inquiry into the full range of choices available to policymakers shows that a particular set of beliefs – the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence – determined options, thus demonstrating the validity of an alternative rationality that standard approaches cannot apprehend. In theoretical terms, a belief-based explanation suggests that international relations and individual states’ foreign policies are not necessarily determined by a uniformly offensive or defensive posture, and that states can pursue more peaceful security strategies than an “anarchic” system has previously allowed. “Security” is not the one-dimensional, militarized state of being most international relations theory implies. Rather, it is a highly subjective, experience-based construct, such that those with different experiences will pursue different means of trying to create their own security. By examining one detailed longitudinal case, which draws on extensive archival research in China, and three shorter cases, it is shown that Chinese foreign policy makers rarely pursued options outside the Five Principles. -

Aid Coordination in Cambodia

CAMBODIA CONSULTATIVE GROUP MEETING PARIS, JULY 1-2, 1997 Public Disclosure Authorized Tableof Content PAGE SUMMARY REPORTOF THE PROCEEDINGS.................................................... 1 I LIST OF ANNEXES Annex 1: List of Participants................................................... 14 OpeningSession Annex 2: Agenda.23 Annex 3: Opening Remarksby Mr. Javad Khalilzadeh-Shirazi,World Bank .. 24 by H.E. Keat Chhon, Sr. Minister in charge Public Disclosure Authorized Annex 4: Opening Remarks of Rehabilitationand Development,Minister of Economy and Finance, Cambodia.27 Macro-EconomicIssues Annex 5: Statement by H.E. Keat Chhon, Cambodia.30 Annex 6: Statement by Mr. Hubert Neiss, IMF.33 Annex 7: Statementby Mr. Kyle Peters, WorldBank .38 Annex 8: Statement by the Delegatefor Japan.41 Annex 9: Statementby the Delegatefor Australia.47 Annex 10: Statementby the Delegate for the United States........................................... 54 Annex 11: Statementby the Delegate for ADB.................................................... 57 Annex 12: Statementby the Delegatefor the EuropeanCommission ............................ 59 Annex 13: Statement by the Delegate for the United NationsAgencies ........................ 61 Public Disclosure Authorized Annex 14: Statement by the Delegatefor Norway.................................................... 64 Annex 14A: Statement by the Delegatefor Denmark . ...................................66 Annex 15: Statement by the Delegatefor Sweden.................................................... 68 Annex -

Malaysia's Foreign Policy from a Constructivist Viewpoint

ௐ 4 ഇ! ࢱ 93-122! 2018 ѐ/؞ཱི !ס έ៉઼ᅫࡁտ؞Ώ! ௐ 14 Taiwan International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 93-122 Winter 2018 馬來西亞的外交政策 ─ 建構主義觀點 ࡰܲ ૩̋ࡊԫ̂ጯ̳ВᙯܼၱᇃӘրઘି ၡ ࢋ гٺၹཌྷ۞៍ᕇྋᛖֽҘֲ۞γϹ߆ඉĄϤޙώኢ͛ဘྏϡ நҜཉᄃˠ˾ඕၹ۞ᙯܼĂ1970 ѐͽֽ݈Ҙֲ۞γϹ߆ඉೀͼ ઼ᔵ֕Ш̚ϲ̙ඕޢщБͽ઼̈́छщБ࠹ᙯĄ1970 ѐͽొ̰ ߏޢĄ1980 ѐͽޘࠧͽವՐՀ̂۞઼ᅫਕ֍͵ڒ᎗ٺ༖Ăҭ߿ Ш߆ඉͽ̈́ 2020 ѐण୕Ăૄώ˯ߏͽགྷᑻ൴णࠎڌݣ࢚ٙᑞထ۞ ጱ۞γϹ߆ඉĄቔኢ͛Ϻந˞ֽҘֲ۞кᙝᙯܼͽ઼̈́д ݑ઼̚ঔ۞ϲٺݑ઼̚ঔ۞ϲಞĂ֭ͷͽ αଐဩֽྋᛖ઼̝ ၹཌྷ۞ఢቑăᄮТă̼͛ă࠹̢៍ăۤົޙಞĄ͛ϐĂඊ۰ᄮࠎ ன၁ཌྷᄃҋϤཌྷĂՀਕྋᛖ઼۞γϹ߆ඉٺĂ࠹ྵه၁ኹඈ៍ ྮशĄ ၹཌྷޙăݑ઼̚ঔăםڌᙯᔣෟĈ Ͽᜋ઼छă ăௐ 4 ഇĞ2018/؞ཱིğס Įέ៉઼ᅫࡁտ؞Ώįௐ 14 94 壹、前言 γϹ߆ٺ၆͞ءΪߏԯֽҘֲڍдኢֽҘֲ۞γϹ߆ඉॡĂт γϹૺ̝ĶֽҘֲķ઼Щரعઇ˘ୃĂּтͽ˭઼߆ڱඉ۞࠻ ኜαঔ࠰Ă֭Їңࣃኢ̝ĞMinistryٸΝĂ၁âइγϹ߆ඉ of Foreign Affairs, 2018ğĄ 【馬來西亞】奉行以和平、人道、正義及平等價值觀為基礎的獨 立原則和務實的外交政策,其外交政策首要目標是保護【馬來西 亞】的主權和國家利益,並透過有效的外交行為為公平與平等的 國際社會做出有意義的貢獻。……【馬來西亞】推動前瞻性和務 實性的外交政策,促進貿易,吸引外國投資,以及作為穩定與和 平的國家。……【馬來西亞】充分致力於推動全球和平安全與繁 榮的多邊主義,在與發展國家的技術合作方面,【馬來西亞】通過 各種外交政策機制,分享經驗與知識並與其他國家進行合作。…… 【馬來西亞】繼續遵循獨立、主權、領土完整和不干涉他國事務 的原則,和平解決爭端,和平共處,互惠互利。 ݑֲ۞ڌдצ˯ޘ̂ޝᇹᙜ΄γĂ઼۞γϹ߆ඉдءੵ˞ֱ পঅгநҜཉͽ̈́প۞ˠ˾ඕၹඈᙯᔣЯ৵۞ᇆᜩĂд̙Тॡഇѣ̙ ТૺĄࠖѩĂώኢ͛дኢֽҘֲγϹ߆ඉॡĂࢋ̶ࠎ̂ొ̶Ă ௐ˘ొ̶Аಶপঅ۞гநҜཉ̈́၆щБ۞நྋүࡦഀ̬Ăͽѩాඕ γϹ߆ඉүࠎĂ֭ኢЯপঅ۞ˠ˾ඕၹĂ۞عЧ࣎߆ޢֽҘֲϲז छ̚Էႊ઼̦ڒϔ઼छĂֽҘֲд᎗۞ٸࠧ̚࠹༊ฟ͵ڒүࠎ᎗ ֎ҒĂপҾߏݑঔજ۞̚ڼᆃ֎Ғĉௐ˟ొ̶ߏଣֽҘֲдડા߆ ၹཌྷޙᒜԊ๕઼̚۞γϹૺĄ͛ϐĂඊ۰ဘྏͽ઼ᅫᙯܼநኢ̚۞ ྋᛖ઼γϹ߆ඉĂ֭ரέ៉д઼۞γϹߛၹ˭ѣң߉˧ᕇүࠎඕᄬĄ 貳、獨立後各政府的外交政策主張 ĆٛતĞTunku Abdul RahmanĂౌܠĆؑڌֽҘֲгநҜཉ۞ࢦࢋّĂϡ ֽҘֲௐ˘Їࢵ࠹Ă1957-70ğ۞ྖֽᄲĂι۞઼˿˘ొ̶гֲ߷̂ౙĂ ၹཌྷ៍ᕇ 95ޙ ֽҘֲ۞γϹ߆ඉǕ ඍᘷᇃ̂Ηफ̚۞˘ొ̶Ą˵Яܝᛂזᄼăາೀֲ̰ޠଂහٺΩ˘ొ̶ᛳ זѩĂֽҘֲ่่̙ߏֲ߷̂ౙᄃֲ߷फᑎ̝ม۞ሇĂՀߏݑ઼̚ঔ ĞTunku Abdul Rahman, 1965: 659ğĄଂϲҌ̫͗ܝ߶̝ม۞υགྷޘО ҘֲВ።གྷ 7 Ҝࢵ࠹1ĂЯࠎгநҜཉ۞ࢦࢋّĂтңӀϡγϹ߆ඉдЕֽ ˠޘૻᚮు۞ᒖဩ̚ჯϠхĉ˫Яࠎˠ˾۞পঅّĂֽˠăරˠăО ˭ߊхᆊࣃЧளĂ઼тңдк۞Ϡၗ˭ჯ઼छхд۞ᆊࣃĉͽ۞ -

The Fight Against International Terrorism: Cambodian Perspective

CICP Working Paper No.23. i No. 23 TThhee Fiigghhtt aggaaiinnsstt Inntteerrnnaattiioonnaall TTeerrrroorriissmm:: A Caammbbooddiiaann PPeerrssppeeccttiivvee Chheang Vannarith And Chap Sotharith April 2008 With Compliments This Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the Cambodian Institute for Cooperation and Peace Published with the funding support from The International Foundation for Arts and Culture, IFAC CICP Working Paper No.23. ii About Cambodian Institute for Cooperation and Peace (CICP) The CICP is an independent, neutral, and non-partisan research institute based in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The Institute promotes both domestic and regional dialogue between government officials, national and international organizations, scholars, and the private sector on issues of peace, democracy, civil society, security, foreign policy, conflict resolution, economics and national development. In this regard, the institute endeavors to: organize forums, lectures, local, regional and international workshops and conference on various development and international issues; design and conduct trainings to civil servants and general public to build capacity in various topics especially in economic development and international cooperation; participate and share ideas in domestic, regional and international forums, workshops and conferences; promote peace and cooperation among Cambodians, as well as between Cambodians and others through regional and international dialogues; and conduct surveys and researches on various topics including socio-economic development, security, strategic studies, international relation, defense management as well as disseminate the resulting research findings. Networking The Institute convenes workshops, seminars and colloquia on aspects of socio-economic development, international relations and security. -

Flt I Lrt HE Dr. Haruhisa Handa Advisor to the Prime

Chairman, Asian Economic Forum H.E. Dr. Haruhisa Handa Advisor to the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Cambodia; Advisor to the Royal Government of Cambodia; Founder and Chairman, Asia Economic Forum; Chancellor, The University of Cambodia; President and Founder, International Foundation for Arts and Culture H.E. Dr. Haruhisa Handa is a highly-praised business man, a respected philanthropist, a successful author, a musician, poet, painter, dancer, and a motivational speaker. He received his B.A. in Economics at Doshisha University and later received an M.A. in Vocal Music from Musashino Academia Musicae. H.E. Dr. Handa went on to acquire an M.A. in Creative Arts from Edith Cowan University in Australia, which also later awarded him an honorary doctorate. He is also an ordained Zen Buddhist priest in the Rinzai tradition. H.E. Dr. Handa has served as a guest lecturer at numerous esteemed universities around the world, sharing his extensive experience and knowledge. Currently, he operates several overseas companies; and serves as Vice-Chairman of the International Shinto Foundation, the President and Founder of the International Foundation for Arts and Culture, the Vice-Chairman of the Sihanouk Hospital, an Advisor to the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Chancellor of the University of Cambodia, and the Founder and Chairman of the Asia Economic Forum (AEF). Vice-Chairman, Asian Economic Forum H.E. Dr. Kao Kim Hourn Advisor to the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Cambodia; Member, Supreme National Economic Council; Secretary of State, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation; Vice-Chairman of AEF; President, The University of Cambodia H.E.