ASEAN and the Environment Sompong Sucharitkul Golden Gate University School of Law, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

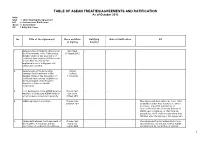

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Edgar Alexander Mearns Papers, Circa 1871-1916, 1934 and Undated

Edgar Alexander Mearns Papers, circa 1871-1916, 1934 and undated Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Series 1: General Correspondence, 1886-1909, and undated................................. 3 Series 2: Biographical Material, 1879, 1885-1900, 1934......................................... 4 Series 3: Field Notes, Research Notes, Specimen Lists, Manuscripts, and Reprints, 1871-1911, and undated.......................................................................................... 5 Series 4: United States-Mexican International Boundary Survey, 1892-1894. Correspondence, Photographs, Drawings, and Research Data on Mammals, circa 1891-1907................................................................................................................ -

Los Cien Montes Más Prominentes Del Planeta D

LOS CIEN MONTES MÁS PROMINENTES DEL PLANETA D. Metzler, E. Jurgalski, J. de Ferranti, A. Maizlish Nº Nombre Alt. Prom. Situación Lat. Long. Collado de referencia Alt. Lat. Long. 1 MOUNT EVEREST 8848 8848 Nepal/Tibet (China) 27°59'18" 86°55'27" 0 2 ACONCAGUA 6962 6962 Argentina -32°39'12" -70°00'39" 0 3 DENALI / MOUNT McKINLEY 6194 6144 Alaska (USA) 63°04'12" -151°00'15" SSW of Rivas (Nicaragua) 50 11°23'03" -85°51'11" 4 KILIMANJARO (KIBO) 5895 5885 Tanzania -3°04'33" 37°21'06" near Suez Canal 10 30°33'21" 32°07'04" 5 COLON/BOLIVAR * 5775 5584 Colombia 10°50'21" -73°41'09" local 191 10°43'51" -72°57'37" 6 MOUNT LOGAN 5959 5250 Yukon (Canada) 60°34'00" -140°24’14“ Mentasta Pass 709 62°55'19" -143°40’08“ 7 PICO DE ORIZABA / CITLALTÉPETL 5636 4922 Mexico 19°01'48" -97°16'15" Champagne Pass 714 60°47'26" -136°25'15" 8 VINSON MASSIF 4892 4892 Antarctica -78°31’32“ -85°37’02“ 0 New Guinea (Indonesia, Irian 9 PUNCAK JAYA / CARSTENSZ PYRAMID 4884 4884 -4°03'48" 137°11'09" 0 Jaya) 10 EL'BRUS 5642 4741 Russia 43°21'12" 42°26'21" West Pakistan 901 26°33'39" 63°39'17" 11 MONT BLANC 4808 4695 France 45°49'57" 06°51'52" near Ozero Kubenskoye 113 60°42'12" c.37°07'46" 12 DAMAVAND 5610 4667 Iran 35°57'18" 52°06'36" South of Kaukasus 943 42°01'27" 43°29'54" 13 KLYUCHEVSKAYA 4750 4649 Kamchatka (Russia) 56°03'15" 160°38'27" 101 60°23'27" 163°53'09" 14 NANGA PARBAT 8125 4608 Pakistan 35°14'21" 74°35'27" Zoji La 3517 34°16'39" 75°28'16" 15 MAUNA KEA 4205 4205 Hawaii (USA) 19°49'14" -155°28’05“ 0 16 JENGISH CHOKUSU 7435 4144 Kyrghysztan/China 42°02'15" 80°07'30" -

Australia and the Origins of ASEAN (1967–1975)

1 Australia and the origins of ASEAN (1967–1975) The origins of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and of Australia’s relations with it are bound up in the period of the Cold War in East Asia from the late 1940s, and the serious internal and inter-state conflicts that developed in Southeast Asia in the 1950s and early 1960s. Vietnam and Laos were engulfed in internal wars with external involvement, and conflict ultimately spread to Cambodia. Further conflicts revolved around Indonesia’s unstable internal political order and its opposition to Britain’s efforts to secure the positions of its colonial territories in the region by fostering a federation that could include Malaya, Singapore and the states of North Borneo. The Federation of Malaysia was inaugurated in September 1963, but Singapore was forced to depart in August 1965 and became a separate state. ASEAN was established in August 1967 in an effort to ameliorate the serious tensions among the states that formed it, and to make a contribution towards a more stable regional environment. Australia was intensely interested in all these developments. To discuss these issues, this chapter covers in turn the background to the emergence of interest in regional cooperation in Southeast Asia after the Second World War, the period of Indonesia’s Konfrontasi of Malaysia, the formation of ASEAN and the inauguration of multilateral relations with ASEAN in 1974 by Gough Whitlam’s government, and Australia’s early interactions with ASEAN in the period 1974‒75. 7 ENGAGING THE NEIGHBOURS The Cold War era and early approaches towards regional cooperation The conception of ‘Southeast Asia’ as a distinct region in which states might wish to engage in regional cooperation emerged in an environment of international conflict and the end of the era of Western colonialism.1 Extensive communication and interactions developed in the pre-colonial era, but these were disrupted thoroughly by the arrival of Western powers. -

A Global Overview of Protected Areas on the World Heritage List of Particular Importance for Biodiversity

A GLOBAL OVERVIEW OF PROTECTED AREAS ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST OF PARTICULAR IMPORTANCE FOR BIODIVERSITY A contribution to the Global Theme Study of World Heritage Natural Sites Text and Tables compiled by Gemma Smith and Janina Jakubowska Maps compiled by Ian May UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre Cambridge, UK November 2000 Disclaimer: The contents of this report and associated maps do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION 1.0 OVERVIEW......................................................................................................................................................1 2.0 ISSUES TO CONSIDER....................................................................................................................................1 3.0 WHAT IS BIODIVERSITY?..............................................................................................................................2 4.0 ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY......................................................................................................................3 5.0 CURRENT WORLD HERITAGE SITES............................................................................................................4 -

ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: from Cold War to Conditionality

ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: From Cold War to Conditionality Lee Jones Abstract Despite their other theoretical differences, virtually all scholars of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) agree that the organisation’s members share an almost religious commitment to the norm of non-intervention. This article disrupts this consensus, arguing that ASEAN repeatedly intervened in Cambodia’s internal political conflicts from 1979-1999, often with powerful and destructive effects. ASEAN’s role in maintaining Khmer Rouge occupancy of Cambodia’s UN seat, constructing a new coalition government-in-exile, manipulating Khmer refugee camps and informing the content of the Cambodian peace process will be explored, before turning to the ‘creeping conditionality’ for ASEAN membership imposed after the 1997 ‘coup’ in Phnom Penh. The article argues for an analysis recognising the political nature of intervention, and seeks to explain both the creation of non- intervention norms, and specific violations of them, as attempts by ASEAN elites to maintain their own illiberal, capitalist regimes against domestic and international political threats. Keywords ASEAN, Cambodia, Intervention, Norms, Non-Interference, Sovereignty Contact Information Lee Jones is a doctoral candidate in International Relations at Nuffield College, Oxford, OX1 1NF, UK. His research focuses on ASEAN and intervention in Cambodia, East Timor, and Burma. Comments are welcomed. Email: [email protected]. Tel/Fax: (+44) (0)1865 28890. ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: -

Birds from Canlaon Volcano in the Highlands of Negros Island in the Philippines

July, 1956 283 BIRDS FROM CANLAON VOLCANO IN THE HIGHLANDS OF NEGROS ISLAND IN THE PHILIPPINES By S. DILLON RIPLEY and D. S. RABOR Several ornithological collectors have worked on Negros Island, which is the fourth largest of the 7090 islands that form the Philippine Archipelago. However, John White- head, the famous English naturalist, was the only person who collected extensively in the highlands of this island. Whitehead worked on the slopes of Canlaon Volcano, in the north-central section in March and April, 1896. Since that time no other collector has visited this volcano until April and May, 1953, when one of us, Rabor, collected in prac- tically the same places in which Whitehead worked. This study of the birds of the high- lands of Negros Island was carried on chiefly through the aid of the Peabody Museum of Natural History of Yale University. TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY OF THE COLLECTING LOCALITIES The principal central mountain chain traverses Negros Island from its northeast corner south to the southern end. This range lies closer to the east side than to the west and forms a divide throughout the extent of the island. A dormant volcano, Canlaon, with an elevation of about 8200 feet, is the most prominent peak in the north-central section of the mountain chain, and it is easily the dominant landmark of the western coastal plain. Many of the mountains of Negros Island are volcanic (Smith, 1924). The north- western region, where most of the sugar cane is grown, is mainly of volcanic origin, whereas the southeastern portion consists of folded and faulted plutonic rocks, slates, and jaspers, probably of Mesozoic Age, and some Tertiary extrusives, all more or less dissected and worn down by erosion. -

The Role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Democracy Support

The role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in post-conflict reconstruction and democracy support www.idea.int THE ROLE OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS IN POST- CONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION AND DEMOCRACY SUPPORT Julio S. Amador III and Joycee A. Teodoro © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance International IDEA Strömsborg SE-103 34, STOCKHOLM SWEDEN Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected], website: www.idea.int The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit thepublication as well as to remix and adapt it provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence see: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-sa/3.0/>. International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Graphic design by Turbo Design CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 4 2. ASEAN’S INSTITUTIONAL MANDATES ............................................................... 5 3. CONFLICT IN SOUTH-EAST ASIA AND THE ROLE OF ASEAN ...... 7 4. ADOPTING A POST-CONFLICT ROLE FOR -

Trust Mountain Climb Challenge

Reaching together! Top of the World Challenge! We can all reach great heights both individually and go further still together. How many of the world’s 100 tallest mountains can we climb as one Trust community? During these challenging times it’s important that we all look after our mental wellbeing and walking is a great way to do this, alongside also improving our physical health. We are going to use this challenge to fundraise for the mental health charity MIND. We’re encouraging children to walk locally with their parents (within the restrictions of Please follow this link to our Just Giving page. lockdown) and measure how far they walk. They can then colour or tick off any mountain of their choice below and share this with their teacher via Seesaw. Everest Each child could walk far enough to climb several mountains over 8 848m the next few weeks. What could a class, a Key Stage K2 - 8611m or a school achieve together? Kangchenjunga - 8586m All school and other Trust staff have the Nanga Parbat 8125m Manaslu 8163m Dhaulagiri I 8167m opportunity to join in too. How high can Batura Sar 7795m Nanda Devi 7816m Annapurna 8091m Kongur Shan 7649m Tirich Mir 7708m Namcha Barwa 7782m everyone in the Trust go? Pik Komm’zma 7495m Minya Konka 7556m Kangkar Punzum 7570m There’s no limit to what we Cerro Aconcagua 6962m Gyalha Peri 7294m Pik Pobeda 7439m can achieve together! Xuelian Feng 6627m Mercedario 6720m Ojos del Salado 6893m Kilimanjaro 5895m Mt Logan 5959m Denali 6194m Chimborazo 6267m Yulong Xueshan 5596m Damavand 5610m Citlaltepetl 5636m -

Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015

Association of Southeast Asian Nations Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 One Vision, One Identity, One Community Association of Southeast Asian Nations Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. For inquiries, contact: Public Affairs Office The ASEAN Secretariat 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 Fax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail : [email protected] General information on ASEAN appears online at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org Catalogue-in-Publication Data Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, April 2009 352.1159 1. ASEAN – Summit – Blueprints 2. Political-Security – Economic – Socio-Cultural ISBN 978-602-8411-04-2 The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgement. Copyright ASEAN Secretariat 2009 All rights reserved ii Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Table of Contents Cha-am Hua Hin Declaration on the Roadmap for the ASEAN Community (2009-2015) ..........................01 ASEAN Political-Security Community Blueprint .........................................................................................05 ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint ....................................................................................................21 -

An Evolving ASEAN: Vision and Reality

Menon • Lee An Evolving ASEAN Vision and Reality The formation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in was originally driven by political and security concerns In the decades that followed ASEAN’s scope evolved to include an ambitious and progressive economic agenda In December the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) was formally launched Although AEC has enjoyed some notable successes the vision of economic integration has yet to be fully realized This publication reviews the evolution of ASEAN economic integration and assesses the major achievements It also examines the challenges that emerged during the past decade and provides recommendations on how to overcome them About the Asian Development Bank AN EVOLVING ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous inclusive resilient and sustainable Asia and the Pacifi c while sustaining its e orts to eradicate extreme poverty Established in it is owned by members— from the region Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue loans equity investments guarantees grants and technical assistance ASEAN: AN EVOLVING ASEAN VISION AND REALITY VISION Edited by Jayant Menon and Cassey Lee SEPTEMBER AND REALITY ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org 9 789292 616946 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK AN EVOLVING ASEAN VISION AND REALITY Edited by Jayant Menon and Cassey Lee SEPTEMBEr 2019 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2019 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. -

The Conservation Status of Biological Resources in the Philippines

: -.^,rhr:"-i-3'^^=£#?^-j^.r-^a^ Sj2 r:iw0,">::^^'^ \^^' Cfl|*ti-»;;^ THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES IN THE PHILIPPINES A RRF'OHT V^Y THK lUCN CONSKRVATION MONITORING CENT:-!E PfcparGd by Roger Cox for the lnLf5rnaLion?.l InsLituLo Cor Knvironment and Development (IIED) February 1988 / fgrMsa^jnt-^'-agyga-- •r-r- ;.«-'> t ^-' isr* 1*.- i^^s. , r^^, ^».|;; ^b-^ ^.*%-^ *i,r^-v . iinnc [ '»/' C'A'. aSM!': Vi - '«.;s^ ; a-* f%h '3;riti7;.:- n'^'ji K ;ii;!'r ' <s:ii.uiy.. viii. K A xo.^ jf^'r;.' 3 10 ciJuJi i\ Ji\{ :::) Jnj:kf- .i. n ( im'.i) •V'lt r'v - -V.-^f~^?fl LP-ife- f^^ s.:.... --11 -^M.jj^^^ riB CC./Sfc^RvAriON .<*TC.rj^. OF EI3U:i' "I.VJ, JbO'TSOURCES ^^a THE PHILIPPlVl'fC ;j^...^..-r'^^ I ilRPOHT BY THK ILCJJ CGJJSIiKVA'ilCN M0N:.V:..):;1NG CKNT ^ Pc'jpas-fjr' ')y Roto* C(/X for the TiKD). {'obruary 1988 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from UNEP-WCIVIC, Cambridge http://www.archive.org/details/conservationstat88coxr . 7' CONTENTS List of Figures, Appendices and Tables iii Summary iy Acknowledgements vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Objectives 3 2 METHODS 4 3. FLORA, VEGETATION AND FOREST COVER 3.1 Description of the natural vegetation 4 3.1.1 The forests 4 3.1.2 Other vegetation types 7 3 2 Conservation status of the Philippine flora 8 3.2.1 Introduction 8 3.2.2 Causes of habitat destruction 9 3.2.3 Threatened plant species 11 3. 2. A Centres of plant diversity and endemism 12 4 COASTAL AND MARINE ECOSYSTEMS 4.1 Background 17 4.2 Mangroves 18 4.3 Coral reefs 19 4.4 Seagrass beds 22 5.