1962 TABLE of CONTENTS Page 1 Forward 2 Opening Remarks Chairman J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Classification of Leotiomycetes

Mycosphere 10(1): 310–489 (2019) www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/10/1/7 Preliminary classification of Leotiomycetes Ekanayaka AH1,2, Hyde KD1,2, Gentekaki E2,3, McKenzie EHC4, Zhao Q1,*, Bulgakov TS5, Camporesi E6,7 1Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650201, Yunnan, China 2Center of Excellence in Fungal Research, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, 57100, Thailand 3School of Science, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, 57100, Thailand 4Landcare Research Manaaki Whenua, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand 5Russian Research Institute of Floriculture and Subtropical Crops, 2/28 Yana Fabritsiusa Street, Sochi 354002, Krasnodar region, Russia 6A.M.B. Gruppo Micologico Forlivese “Antonio Cicognani”, Via Roma 18, Forlì, Italy. 7A.M.B. Circolo Micologico “Giovanni Carini”, C.P. 314 Brescia, Italy. Ekanayaka AH, Hyde KD, Gentekaki E, McKenzie EHC, Zhao Q, Bulgakov TS, Camporesi E 2019 – Preliminary classification of Leotiomycetes. Mycosphere 10(1), 310–489, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/10/1/7 Abstract Leotiomycetes is regarded as the inoperculate class of discomycetes within the phylum Ascomycota. Taxa are mainly characterized by asci with a simple pore blueing in Melzer’s reagent, although some taxa have lost this character. The monophyly of this class has been verified in several recent molecular studies. However, circumscription of the orders, families and generic level delimitation are still unsettled. This paper provides a modified backbone tree for the class Leotiomycetes based on phylogenetic analysis of combined ITS, LSU, SSU, TEF, and RPB2 loci. In the phylogenetic analysis, Leotiomycetes separates into 19 clades, which can be recognized as orders and order-level clades. -

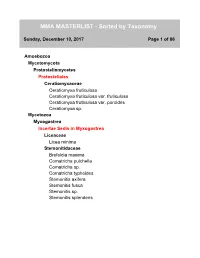

MMA MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy

MMA MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy Sunday, December 10, 2017 Page 1 of 86 Amoebozoa Mycetomycota Protosteliomycetes Protosteliales Ceratiomyxaceae Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. fruticulosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. poroides Ceratiomyxa sp. Mycetozoa Myxogastrea Incertae Sedis in Myxogastrea Liceaceae Licea minima Stemonitidaceae Brefeldia maxima Comatricha pulchella Comatricha sp. Comatricha typhoides Stemonitis axifera Stemonitis fusca Stemonitis sp. Stemonitis splendens Chromista Oomycota Incertae Sedis in Oomycota Peronosporales Peronosporaceae Plasmopara viticola Pythiaceae Pythium deBaryanum Oomycetes Saprolegniales Saprolegniaceae Saprolegnia sp. Peronosporea Albuginales Albuginaceae Albugo candida Fungus Ascomycota Ascomycetes Boliniales Boliniaceae Camarops petersii Capnodiales Capnodiaceae Scorias spongiosa Diaporthales Gnomoniaceae Cryptodiaporthe corni Sydowiellaceae Stegophora ulmea Valsaceae Cryphonectria parasitica Valsella nigroannulata Elaphomycetales Elaphomycetaceae Elaphomyces granulatus Elaphomyces sp. Erysiphales Erysiphaceae Erysiphe aggregata Erysiphe cichoracearum Erysiphe polygoni Microsphaera extensa Phyllactinia guttata Podosphaera clandestina Uncinula adunca Uncinula necator Hysteriales Hysteriaceae Glonium stellatum Leotiales Bulgariaceae Crinula caliciiformis Crinula sp. Mycocaliciales Mycocaliciaceae Phaeocalicium polyporaeum Peltigerales Collemataceae Leptogium cyanescens Lobariaceae Sticta fimbriata Nephromataceae Nephroma helveticum Peltigeraceae Peltigera evansiana Peltigera -

Pseudotsuga Menziesii)

120 - PART 1. CONSENSUS DOCUMENTS ON BIOLOGY OF TREES Section 4. Douglas-Fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) 1. Taxonomy Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirbel) Franco is generally called Douglas-fir (so spelled to maintain its distinction from true firs, the genus Abies). Pseudotsuga Carrière is in the kingdom Plantae, division Pinophyta (traditionally Coniferophyta), class Pinopsida, order Pinales (conifers), and family Pinaceae. The genus Pseudotsuga is most closely related to Larix (larches), as indicated in particular by cone morphology and nuclear, mitochondrial and chloroplast DNA phylogenies (Silen 1978; Wang et al. 2000); both genera also have non-saccate pollen (Owens et al. 1981, 1994). Based on a molecular clock analysis, Larix and Pseudotsuga are estimated to have diverged more than 65 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous to Paleocene (Wang et al. 2000). The earliest known fossil of Pseudotsuga dates from 32 Mya in the Early Oligocene (Schorn and Thompson 1998). Pseudostuga is generally considered to comprise two species native to North America, the widespread Pseudostuga menziesii and the southwestern California endemic P. macrocarpa (Vasey) Mayr (bigcone Douglas-fir), and in eastern Asia comprises three or fewer endemic species in China (Fu et al. 1999) and another in Japan. The taxonomy within the genus is not yet settled, and more species have been described (Farjon 1990). All reported taxa except P. menziesii have a karyotype of 2n = 24, the usual diploid number of chromosomes in Pinaceae, whereas the P. menziesii karyotype is unique with 2n = 26. The two North American species are vegetatively rather similar, but differ markedly in the size of their seeds and seed cones, the latter 4-10 cm long for P. -

AGROFOR International Journal

AGROFOR International Journal PUBLISHER University of East Sarajevo, Faculty of Agriculture Vuka Karadzica 30, 71123 East Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Telephone/fax: +387 57 340 401; +387 57 342 701 Web: www.agrofor.rs.ba; Email: [email protected] EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Vesna MILIC (BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA) MANAGING EDITORS Dusan KOVACEVIC (SERBIA); Sinisa BERJAN (BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA); Noureddin DRIOUECH (ITALY) EDITORIAL BOARD Dieter TRAUTZ (GERMANY); Hamid El BILALI (ITALY); William H. MEYERS (USA); Milic CUROVIC (MONTENEGRO); Tatjana PANDUREVIC (BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA); Alexey LUKIN (RUSSIA); Machito MIHARA (JAPAN); Abdulvahed KHALEDI DARVISHAN (IRAN); Viorel ION (ROMANIA); Novo PRZULJ (BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA); Steve QUARRIE (UNITED KINGDOM); Hiromu OKAZAWA (JAPAN); Snezana JANKOVIC (SERBIA); Naser SABAGHNIA (IRAN); Sasa ORLOVIC (SERBIA); Sanja RADONJIC (MONTENEGRO); Junaid Alam MEMON (PAKISTAN); Vlado KOVACEVIC (CROATIA); Marko GUTALJ (BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA); Dragan MILATOVIC (SERBIA); Pandi ZDRULI (ITALY); Zoran JOVOVIC (MONTENEGRO); Vojislav TRKULJA (BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA); Zoran NJEGOVAN (SERBIA); Adriano CIANI (ITALY); Aleksandra DESPOTOVIC (MONTENEGRO); Igor DJURDJIC (BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA); Stefan BOJIC (BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA); Julijana TRIFKOVIC (BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA) TECHNICAL EDITORS Milan JUGOVIC (BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA) Luka FILIPOVIC (MONTENEGRO) Frequency: 3 times per year Number of copies: 300 ISSN 2490-3434 (Printed) ISSN 2490-3442 (Online) CONTENT BIOMASS PRODUCTION OF MORINGA (Moringa oleifera L.) AT VARIOUS -

Phylogenetic Identification of Pathogenic and Endophytic Fungal Populations in West Coast Douglas-Fir (Pseudotsuga Menziesii) Foliage

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Hazel A. Daniels for the degree of Master of Science in Sustainable Forest Management presented on September 19, 2017. Title: Phylogenetic Identification of Pathogenic and Endophytic Fungal Populations in West Coast Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) Foliage. Abstract approved: _____________________________________________________ James D. Kiser Douglas-fir provides social, economic, and ecological benefits in the Pacific Northwest (PNW). In addition to timber, forests support abundant plant and animal biodiversity and provide socioeconomic viability for many rural communities. Products derived from Douglas- fir account for approximately 17% of the U.S. lumber output with an estimated value of $1.9 billion dollars. Employment related to wood production accounts for approximately 61,000 jobs in Oregon. Timberland also supports water resources, recreation, and wildlife habitat. Minor defoliation has previously been linked to Swiss Needle Cast, associated with the fungus Phaeocryptopus gaeumannii, however, unprecedented large-scale defoliation began in the 1990s and has increased since, leading to decreased growth and yield. Areas affected areas by SNC exceed 500,000 acres in Oregon. Defoliation symptoms are inconsistent with predicted effects of P. gaeumannii, and targeted chemical control has had mixed results. While the microbiome community of conifer needles is poorly described to date, we hypothesize the full interstitial microbiome complex is involved in disease response in conifers. There are at least three known pathogenic endophytes of Douglas-fir, in addition to a large number of endophytes with undetermined host relationships. In order to understand the mechanistic dynamics of needle cast, it is necessary to uncover the underlying cause of the symptoms. -

A Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Investigation of Conifer Endophytes

A Taxonomic and Phylogenetic Investigation of Conifer Endophytes of Eastern Canada by Joey B. Tanney A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016 Abstract Research interest in endophytic fungi has increased substantially, yet is the current research paradigm capable of addressing fundamental taxonomic questions? More than half of the ca. 30,000 endophyte sequences accessioned into GenBank are unidentified to the family rank and this disparity grows every year. The problems with identifying endophytes are a lack of taxonomically informative morphological characters in vitro and a paucity of relevant DNA reference sequences. A study involving ca. 2,600 Picea endophyte cultures from the Acadian Forest Region in Eastern Canada sought to address these taxonomic issues with a combined approach involving molecular methods, classical taxonomy, and field work. It was hypothesized that foliar endophytes have complex life histories involving saprotrophic reproductive stages associated with the host foliage, alternative host substrates, or alternate hosts. Based on inferences from phylogenetic data, new field collections or herbarium specimens were sought to connect unidentifiable endophytes with identifiable material. Approximately 40 endophytes were connected with identifiable material, which resulted in the description of four novel genera and 21 novel species and substantial progress in endophyte taxonomy. Endophytes were connected with saprotrophs and exhibited reproductive stages on non-foliar tissues or different hosts. These results provide support for the foraging ascomycete hypothesis, postulating that for some fungi endophytism is a secondary life history strategy that facilitates persistence and dispersal in the absence of a primary host. -

Douglas-Fir What Science Can Tell Us – an Option for Europe

Douglas-fir What Science Can Tell Us – an option for Europe Heinrich Spiecker, Marcus Lindner and Johanna Schuler (editors) What Science Can Tell Us 9 2019 What Science Can Tell Us Lauri Hetemäki, Editor-In-Chief Georg Winkel, Associate Editor Pekka Leskinen, Associate Editor Minna Korhonen, Managing Editor The editorial office can be contacted at [email protected] Layout: Grano Oy / Jouni Halonen Printing: Grano Oy Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the European Forest Institute. ISBN 978-952-5980-65-3 (printed) ISBN 978-952-5980-66-0 (pdf) Douglas-fir What Science Can Tell Us – an option for Europe Heinrich Spiecker, Marcus Lindner and Johanna Schuler (editors) Funded by the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union This publication is based upon work from COST Action FP1403 NNEXT, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). www.cost.eu Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................9 Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................11 Executive summary ...........................................................................................................13 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................17 Heinrich Spiecker and Johanna Schuler 2. Douglas-fir -

Unclassified ENV/JM/MONO(2008)30

Unclassified ENV/JM/MONO(2008)30 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 28-Nov-2008 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English - Or. English ENVIRONMENT DIRECTORATE JOINT MEETING OF THE CHEMICALS COMMITTEE AND Unclassified ENV/JM/MONO(2008)30 THE WORKING PARTY ON CHEMICALS, PESTICIDES AND BIOTECHNOLOGY SERIES ON HARMONISATION OF REGULATORY OVERSIGHT IN BIOTECHNOLOGY Number 43 CONSENSUS DOCUMENT ON THE BIOLOGY OF DOUGLAS-FIR (Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco) English - Or. English JT03256472 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format ENV/JM/MONO(2008)30 Also published in the Series on Harmonisation of Regulatory Oversight in Biotechnology: No. 1, Commercialisation of Agricultural Products Derived through Modern Biotechnology: Survey Results (1995) No. 2, Analysis of Information Elements Used in the Assessment of Certain Products of Modern Biotechnology (1995) No. 3, Report of the OECD Workshop on the Commercialisation of Agricultural Products Derived through Modern Biotechnology (1995) No. 4, Industrial Products of Modern Biotechnology Intended for Release to the Environment: The Proceedings of the Fribourg Workshop (1996) No. 5, Consensus Document on General Information concerning the Biosafety of Crop Plants Made Virus Resistant through Coat Protein Gene-Mediated Protection (1996) No. 6, Consensus Document on Information Used in the Assessment of Environmental Applications Involving Pseudomonas (1997) No. 7, Consensus Document on the Biology of Brassica napus L. (Oilseed Rape) (1997) No. 8, Consensus Document on the Biology of Solanum tuberosum subsp. tuberosum (Potato) (1997) No. 9, Consensus Document on the Biology of Triticum aestivum (Bread Wheat) (1999) No. -

Phylogeny of Cyttaria Inferred from Nuclear and Mitochondrial Sequence and Morphological Data

Phylogeny of Cyttaria inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial sequence and morphological data The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Peterson, K. R., and D. H. Pfister. 2010. Phylogeny of Cyttaria Inferred from Nuclear and Mitochondrial Sequence and Morphological Data. Mycologia 102, no. 6: 1398–1416. doi:10.3852/10-046. Published Version doi:10.3852/10-046 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:30168159 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mycologia, 102(6), 2010, pp. 1398–1416. DOI: 10.3852/10-046 # 2010 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 Phylogeny of Cyttaria inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial sequence and morphological data Kristin R. Peterson1 sort into clades according to their associations with Donald H. Pfister subgenera Lophozonia and Nothofagus. Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Key words: Encoelioideae, Leotiomycetes, Notho- Harvard University, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, fagus, southern hemisphere Massachusetts 02138 INTRODUCTION Abstract: Cyttaria species (Leotiomycetes, Cyttar- Species belonging to Cyttaria (Leotiomycetes, Cyttar- iales) are obligate, biotrophic associates of Nothofagus iales) have interested evolutionary biologists since (Hamamelididae, Nothofagaceae), the southern Darwin (1839), who collected on his Beagle voyage beech. As such Cyttaria species are restricted to the their spherical, honeycombed fruit bodies in south- southern hemisphere, inhabiting southern South ern South America (FIG. -

An Abstract of the Thesis Of

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Lilah Gonen for the degree of Master of Science in Botany and Plant Pathology presented on December 9, 2020. Title: Community Ecology of Foliar Fungi and Oomycetes of Pseudotsuga menziesii on the Pacific Northwest Coast. Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________________________ Andy Jones Jared LeBoldus Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii (coast Douglas-fir) is a tree of ecological, economic, and cultural value in its native North American Pacific Northwest (PNW) distribution. P. menziesii is host to a variety of well- documented endophytic foliar microorganisms, including the fungus Nothophaeocryptopus gaeumannii, the causal agent of Swiss needle cast (SNC), and the oomycete Phytophthora pluvialis, which causes cryptic disease symptoms in P. menziesii. Little is understood about how entire foliar microbial communities are structured by geography, climate, and host lineage, nor how foliar fungi and oomycetes interact at the tree level. This study used a large-scale reciprocal transplant experiment, next-generation sequencing (NGS), and culture-based methods to characterize the diversity and structure of foliar fungi and oomycetes of P. menziesii across three sites on the PNW coast. Fungal community composition within trees was structured by host location (p = 1e-4, 1.5e-3) as well as interactions between host location and lineage (p = 0.02, 6.4e- 3, 8e-4). Oomycete communities were dominated by a single OTU, assigned to Phytophthora cacuminis, a recently described species in Australia. An undescribed Pythium species was isolated in culture from 18 trees throughout the study sites. Generalized linear mixed models revealed that fungal community richness was positively correlated to oomycete community richness among trees (estimated coefficient = 0.14, p = 8.3e-16), and that presence of P. -

Endophytic Fungi in Forest Trees: Are They Mutualists?

fungal biology reviews 21 (2007) 75–89 journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fbr Review Endophytic fungi in forest trees: are they mutualists? Thomas N. SIEBER* Forest Pathology and Dendrology, Institute of Integrative Biology (IBZ), ETH Zurich, CH-8092 Zurich, Switzerland article info abstract Article history: Forest trees form symbiotic associations with endophytic fungi which live inside healthy Received 26 February 2007 tissues as quiescent microthalli. All forest trees in temperate zones host endophytic fungi. Received in revised form The species diversity of endophyte communities can be high. Some tree species host more 24 April 2007 than 100 species in one tissue type, but communities are usually dominated by a few host- Accepted 15 May 2007 specific species. The endophyte communities in angiosperms are frequently dominated by Published online 14 June 2007 species of Diaporthales and those in gymnosperms by species of Helotiales. Divergence of angiosperms and gymnosperms coincides with the divergence of the Diaporthales and the Keywords: Helotiales in the late Carboniferous about 300 million years (Ma) ago, indicating that the Antagonism Diaporthalean and Helotialean ancestors of tree endophytes had been associated, respec- Apiognomonia errabunda tively, with angiosperms and gymnosperms since 300 Ma. Consequently, dominant tree Biodiversity endophytes have been evolving with their hosts for millions of years. High virulence of Commensalism such endophytes can be excluded. Some are, however, opportunists and can cause disease Evolution after the host has been weakened by some other factor. Mutualism of tree endophytes is Fomes fomentarius often assumed, but evidence is mostly circumstantial. The sheer impossibility of producing Mutualism endophyte-free control trees impedes proof of mutualism. -

Characterising Plant Pathogen Communities and Their Environmental Drivers at a National Scale

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Characterising plant pathogen communities and their environmental drivers at a national scale A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Lincoln University by Andreas Makiola Lincoln University, New Zealand 2019 General abstract Plant pathogens play a critical role for global food security, conservation of natural ecosystems and future resilience and sustainability of ecosystem services in general. Thus, it is crucial to understand the large-scale processes that shape plant pathogen communities. The recent drop in DNA sequencing costs offers, for the first time, the opportunity to study multiple plant pathogens simultaneously in their naturally occurring environment effectively at large scale. In this thesis, my aims were (1) to employ next-generation sequencing (NGS) based metabarcoding for the detection and identification of plant pathogens at the ecosystem scale in New Zealand, (2) to characterise plant pathogen communities, and (3) to determine the environmental drivers of these communities. First, I investigated the suitability of NGS for the detection, identification and quantification of plant pathogens using rust fungi as a model system.