Live from the Met: Digital Broadcast Cinema, Medium Theory, and Opera for the Masses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doc Nyc Announces Final Titles Including

DOC NYC ANNOUNCES FINAL TITLES INCLUDING WORLD PREMIERE OF BRUCE SPRINGSTREEN & THE E STREET BAND’S “DARKNESS ON THE EDGE OF TOWN” CONCERT FILM AT ZIEGFELD THEATER ON NOVEMBER 4TH AND “MOMENTS OF TRUTH” FEATURING ALEC BALDWIN AND OTHER FAMOUS FIGURES DISCUSSING THEIR FAVORITE DOC MOMENTS New York, NY, October 19th 2010 - DOC NYC, New York’s Documentary Festival, announced its final slate of titles including the world premiere of “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” a new concert film with Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band performing their classic album. The film will screen at the Ziegfeld Theatre on November 4. Directed by the Grammy and Emmy award winner Thom Zimny, the film was shot last year at the Paramount Theatre in Asbury Park, NJ in an unconventional manner without any audience in attendance. Springsteen’s manager Jon Landau has said this presentation “best captures the starkness of the original album.” The film will be released on DVD as part of the box set “The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story” later in November. “We wanted to give fans a one night only opportunity to see this spectacular performance on the Ziegfeld’s big screen,” said DOC NYC Artistic Director Thom Powers. A portion of the proceeds from this screening will be donated to the Danny Fund/Melanoma Research Alliance – a non-profit foundation devoted to advancing melanoma research and awareness set up after the 2008 passing of Danny Federici, longtime Springsteen friend and E-Street Band member. DOC NYC will help launch a new promo campaign of shorts called “Moments of Truth,” in which noteworthy figures (actors, politicians, musicians, etc) describe particular documentary moments that moved them. -

The Arrival of the First Film Sound Systems in Spain (1895-1929)

Journal of Sound, Silence, Image and Technology 27 Issue 1 | December 2018 | 27-41 ISSN 2604-451X The arrival of the first film sound systems in Spain (1895-1929) Lidia López Gómez Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona [email protected] Date received: 10-01-2018 Date of acceptance: 31-03-2018 PALABRAS CLAVE: CINE MUDO | SONIDO | RecepcIÓN | KINETÓFONO | CHRONOPHONE | PHONOFILM KEY WORDS: SILENT FILM | SOUND | RecepTION | KINETOPHONE | CHRONOPHONE | PHONOFILM Journal of Sound, Silence, Image and Technology | Issue 1 | December 2018. 28 The arrival of the first film sound systems in spain (1895-1929) ABSTracT During the final decade of the 19th century, inventors such as Thomas A. Edison and the Lumière brothers worked assiduously to find a way to preserve and reproduce sound and images. The numerous inventions conceived in this period such as the Kinetophone, the Vitascope and the Cinematograph are testament to this and are nowadays consid- ered the forerunners of cinema. Most of these new technologies were presented at public screenings which generated a high level of interest. They attracted people from all social classes, who packed out the halls, theatres and hotels where they were held. This paper presents a review of the newspa- per and magazine articles published in Spain at the turn of the century in order to study the social reception of the first film equip- ment in the country, as well as to understand the role of music in relation to the images at these events and how the first film systems dealt with sound. Journal of Sound, Silence, Image and Technology | Issue 1 | December 2018. -

Catalogue Festival International Ciné

sommaire / summary PRÉSENTATION GÉNÉRALE PRESENTATION GENERALE 48 Monstres / Monsters 3 Sommaire / Summary 51 Soirée courts métrages « Attaque des PsychoZombies » / 4 Editos / Forewords "PsychoZombies’ Attack" short films night 12 Jurys officiels / Official juries 16 Invités / Guests 18 Cérémonies d'ouverture et de palmarès / Opening and HOMMAGE ANIME AU STUDIO GHIBLI palmares ceremonies 52 Conférence / Conference 20 Fête des enfants / Kids party 52 Rétrospective Studio Ghibli / Retrospective 55 Exposition - « Hayao Miyazaki en presse » / Exhibition COMPETITIONS INTERNATIONALES 22 Longs métrages inédits / Unreleased feature films AUTOUR DES FILMS 32 Courts métrages ados / Teenager short films 56 Séminaire « Les outils numériques dans l’éducation à 34 Courts métrages d'animation / Short animated films l’image » / Seminar 57 Ateliers et animations / Workshops and activities 60 Rencontres et actions éducatives / Meetings and educational INEDITS ET AVANT-PREMIERES HORS actions COMPETITION 65 Décentralisation / Decentralization 38 Ciné-bambin / Toddlers film 38 Séances scolaires et familles / School and family screenings 43 Séances scolaires et ado-adultes / Youth and adults screenings INFOS PRATIQUES 66 Equipe et remerciements / Team and thanks 68 Contacts / Print sources THEMATIQUE «CINEMA FANTASTIQUE» 70 Lieux du festival / Venues 44 Ciné-concert / Concert film 72 Réservations et tarifs / Booking and prices 45 Robots et mondes futuristes / Robots and futuristic worlds 74 Grille programme à Saint-Quentin / Schedule in Saint-Quentin 46 Magie, contes et mondes imaginaires / Magic, tales and 78 Index / Index imaginary worlds 79 Partenaires / Partnerships and sponsors éditos / foreword Une 33ème édition sous le Haut-Patronage de Madame Najat VALLAUD- BELKACEM, Ministre de l'éducation nationale, de l'enseignement supérieur et de la recherche. Ciné-Jeune est fantastique ! L’édition 2015 du Festival s’est donné pour thème le « Cinéma fantastique ». -

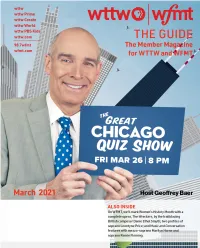

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

History of Communications Media

History of Communications Media Class 5 History of Communications Media • What We Will Cover Today – Photography • Last Week we just started this topic – Typewriter – Motion Pictures • The Emergence of Hollywood • Some Effects of the Feature Film Photography - Origins • Joseph Nicephore Niepce –first photograph (1825) – Used bitumen and required an 8-hour exposure – Invented photoengraving • Today’s photolithography is both a descendent of Niepce’s technique and the means by which printed circuits and computer chips are made – Partner of Louis Daguerre Photography - Origins • Louis Daguerre – invented daguerreotype – Daguerre was a panorama painter and theatrical designer – Announced the daguerreotype system in 1839 • Daguerreotype – a photograph in which the image is exposed onto a silver mirror coated with silver halide particles – The first commercially practical photographic process • Exposures of 15 minutes initially but later shortened – The polaroid of its day – capable of only a single image Photography – Origins • William Henry Fox Talbot – invented the calotype or talbotype – Calotype was a photographic system that: • Used salted paper coated with silver iodide or silver chloride that was developed with gallic acid and fixed with potassium bromide • Produced both a photographic negative and any desired number of positive prints Photography – Origins • Wet Collodion Process - 1 – Invented in 1850 by Frederick Scott Archer and Gustave Le Grey – Wet plate process that required the photographer to coat the glass plate, expose it, -

PDF Portfolio

lauryn schrom GRAPHIC DESIGNER | ILLUSTRATOR [email protected] www.schromcreative.com sneak peek party invite & program An invitation and program handout for a season preview event at Capital Repertory Theatre in Albany, NY. Different textures (paint, wood, velvet, and abstract lighting) peek out of a patchwork set of shapes, suggesting an unforgettable preview night emblematic of a diverse new season. SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Project type: Print Design, Production Design Created with Adobe InDesign, Adobe Photoshop 6 – 7 P.M. in the Lobby YOU ARE CORDIALLY INVITED Music featuring Peter Darling TO CAPITAL REPERTORY THEATRE’S Beer/Wine & Light Fare: • C.H. Evans Brewing Company at the Albany Pump Station SNEAK • Angelo’s 677 Prime • The Hollow Bar + Kitchen PREVIEW • The Merry Monk PEEK PARTY • Yono’s/dp An American Brasserie 7 P.M. in the Theatre Welcome to our 2017–2018 Bank of America Season at theREP! Monday, September 18, 2017 • 6 – 9 p.m. SNEAK Casting! 7:50 – 8:30 P.M. PREVIEW Stars of theREP perform excerpts from PARTY Sex with Strangers, She Loves Me, Paris PEEK Time, Mamma Mia (sing along), Alice In JOIN US Wonderland, The Humans, Shakespeare: The Remix and Blithe Spirit The Sneak Peek Party is our way of giving back to our family of friends who keep our star shining, your generosity makes it happen! 8:30 – 9 P.M. in the Lobby Let us thank you for your support. Join us for complimentary music, wine bar, Dessert & Champagne: delicious food samplings from our restaurant partners, dessert, a champagne Dessert courtesy of Bella Napoli – toast, and a program featuring the real stars of theREP—YOU! Italian-American Bakery & Café Cocktail hour starts 6 p.m. -

Mcbastard's MAUSOLEUM: DVD Review: IGGY & the STOOGES: RAW POW

McBASTARD'S MAUSOLEUM: DVD Review: IGGY & THE STOOGES: RAW POW... Page 1 of 40 Share Report Abuse Next Blog » Create Blog Sign In McBASTARD'S MAUSOLEUM indie, horror, and cult cinema blog. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2011 CONTRIBUTORS DVD Review: IGGY & THE STOOGES: RAW POWER LIVE IN THE HANDS OF FANS (2011) Christopher Kahler McBastard Root Rot CONTACT To submit materials for review please email me for the address. I am also willing to accept reviews, articles and other content for the site. email: [email protected] twitter: http://twitter.com/mcbastard2000 facebook: http://www.facebook.com/pages/mcBast ards-mausoleum/169440663073382 tumblr: http://mcbastardsmausoleum.tumblr.co m/ IGGY AND THE STOOGES digg: http://digg.com/mcbastard2000 RAW POWER LIVE IN THE HANDS OF FANS (2010) stumbleupon: http://www.stumbleupon.com/stumbler/ LABEL: MVD Visual McBastard2000/reviews/ REGION CODE: 1 NTSC RATING: Unrated THE CRYPT DURATION: 81 mins AUDIO:Dolby Digital 2.0. 51 ▼ 2011 (262) VIDEO: 16:9 Widescreen ▼ October (18) DIRECTOR:Joey Carry Extreme Horror Film THE BUNNY GAME Banned in the U... Filmed towards the end of their 2010 reunion tour RAW POWER LIVE IN THE HANDS Blu-ray Review: HALLOWEEN: THE OF FANS captures Iggy and the Stooges blistering live performance of the classic CURSE OF MICHAEL MY... RAW POWER (1973) album at the All Tomorrow's Parties Festival in Monticello, New Schlocky B-Movie York. The performance was filmed by six contestants who entered an online contest Anthology 'CHILLERAMA' on Blu- for a chance to both meet and document the band at this very performance. The ray.. -

Action | Adventure | Comedy | Crime & Gangster | Drama

Genres and generic conventions Below is a list of some of the main genres in film. For each genre there are broad descriptions of typical plots and characters, some aspects of mise- en-scene and theme. Genre is a very fluid idea however, and a film may not easily fit into just one genre, so sub-genres are also listed. Each description features some gaps for you to fill in- these are the names of each genre. Read the description carefully and choose one of the following genres to add into the gaps. ACTION | ADVENTURE | COMEDY | CRIME & GANGSTER | DRAMA | EPICS & HISTORICAL | HORROR | MUSICAL | SCIENCE FICTION | WAR | WESTERNS EXTENSION: for each, list 2 or 3 reasons why each example film fits in with that genre. Conventions Example films _______ are serious films. They are driven by intense plots that aim to portray realistic characters, settings, situations and stories that involve intense character development. ______ tend to eschew special-effects or action though some of these elements may feature. Traditionally, ______ films are probably the largest film genre but perhaps because it is a very broad genre that can apply to a wide range of sub genres. Some examples include melodramas, epics (historical dramas), or romantic genres. ______ biographical films (or "biopics") are a major sub-genre. 1 _________ films are exciting stories, with interesting experiences and set pieces set in a variety of exotic locales. Whilst featuring many similar aspects to the action genre, _______ films tend to see characters travelling around trying to find a Macguffin. These films can include traditional swashbucklers, serialised films, expeditions for lost continents, explorations of jungles, deserts or even space, treasure hunts and any other form of “search” or “hunt”. -

A Genealogy of the Music Mockumentary

Sheridan College SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences Books & Chapters (FHASS) 5-8-2019 It’s Such a Fine Line Between Stupid and Clever: A Genealogy of the Music Mockumentary Michael Brendan Baker Sheridan College, [email protected] Peter Lester Follow this and additional works at: https://source.sheridancollege.ca/fhass_books Part of the Music Commons SOURCE Citation Baker, Michael Brendan and Lester, Peter, "It’s Such a Fine Line Between Stupid and Clever: A Genealogy of the Music Mockumentary" (2019). Books & Chapters. 9. https://source.sheridancollege.ca/fhass_books/9 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences (FHASS) at SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books & Chapters by an authorized administrator of SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 29 “It’S SUCH A FINE LINE BETWEEN STUPID AND CLEVER” A Genealogy of the Music Mockumentary Michael Brendan Baker and Peter Lester Imitation is the sincerest [form] of flattery. —Charles Caleb Colton, 1820 In 1934, on the Aran Islands off the western coast of Ireland, pioneering filmmaker Robert Flaherty and his crew were collecting material for a feature-length nonfiction film documenting the premodern conditions endured by residents of the rough North Atlantic outpost. Discussing the ways in which Flaherty prearranged character interactions and informally scripted many of the scenarios that would ultimately feature in his films, camera assistant John Taylor later recalled for filmmaker George Stoney that he wrote in his notebooks at the time the word “mockumentary” to describe this creative treatment of the nonfictional material How( ). -

The Emergence of Abstract Film in America Was Organized by Synchronization with a Musical Accompaniment

EmergenceFilmFilmFilmArchiveinArchivesAmerica, The Abstract Harvard Anthology Table of Contents "Legacy Alive: An Introduction" by Bruce Posner . ... ... ... ... ..... ... ... ... ... ............ ....... ... ... ... ... .... .2 "Articulated Light: An Appendix" by Gerald O'Grady .. ... ... ...... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...... ... ... ... ... ... .... .3 "Cinema as a An Form: Avant-Garde " Experimentation " Abstraction" by Vlada Petric .. ... 3 "A New RealismThe Object" by Fernand Leger ... ........ ... ... ... ...... ........ ... ... ... ... .... ... .......... .4 "True Creation" by Oskar Fischinger .. ..... ... ... ... ... .. ...... ... ....... ... ........... ... ... ... ... ... ....... ... ........4 "Observable Forces" by Harry Smith . ... ... ... ... ... ... ...... ... ... ... ... ......... ... ... ... .......... ...... ... ... ... ......5 "Images of Nowhere" by Raul Ruiz ......... ... ... ........ ... ... ... ... ... ...... ... ... ... ... ... ...... ... ... .... ... ... ... 5 `TIME. .. on dit: Having Declared a Belief in God" by Stan Brakhage ..... ...... ............. ... ... ... .. 6 "Hilla Rebay and the Guggenheim Nexus" by Cecile Starr ..... ... ...... ............ ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...7 Mary Ellen Bute by Cecile Starr .. ... ... ... ... ...... ... ... ... ... ... ............ ... ...... ... ... ... ... ... ...... ... .............8 James Whitney studying water currents for Wu Ming (1973) Statement I by Mary Ellen Bute ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...... ...... ... ... ...... ... ... ... ... .. -

Soviet Science Fiction Movies in the Mirror of Film Criticism and Viewers’ Opinions

Alexander Fedorov Soviet science fiction movies in the mirror of film criticism and viewers’ opinions Moscow, 2021 Fedorov A.V. Soviet science fiction movies in the mirror of film criticism and viewers’ opinions. Moscow: Information for all, 2021. 162 p. The monograph provides a wide panorama of the opinions of film critics and viewers about Soviet movies of the fantastic genre of different years. For university students, graduate students, teachers, teachers, a wide audience interested in science fiction. Reviewer: Professor M.P. Tselysh. © Alexander Fedorov, 2021. 1 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 1. Soviet science fiction in the mirror of the opinions of film critics and viewers ………………………… 4 2. "The Mystery of Two Oceans": a novel and its adaptation ………………………………………………….. 117 3. "Amphibian Man": a novel and its adaptation ………………………………………………………………….. 122 3. "Hyperboloid of Engineer Garin": a novel and its adaptation …………………………………………….. 126 4. Soviet science fiction at the turn of the 1950s — 1960s and its American screen transformations……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 130 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 136 Filmography (Soviet fiction Sc-Fi films: 1919—1991) ……………………………………………………………. 138 About the author …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 150 References……………………………………………………………….……………………………………………………….. 155 2 Introduction This monograph attempts to provide a broad panorama of Soviet science fiction films (including television ones) in the mirror of -

Redalyc.Los Inicios Del Cine Sonoro Y La Creación De Nuevas Empresas Fílmicas En México (1928-1931)

Revista del Centro de Investigación. Universidad La Salle ISSN: 1405-6690 [email protected] Universidad La Salle México Vidal Bonifaz, Rosario Los inicios del cine sonoro y la creación de nuevas empresas fílmicas en México (1928-1931) Revista del Centro de Investigación. Universidad La Salle, vol. 8, núm. 29, enero-junio, 2008, pp. 17- 28 Universidad La Salle Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=34282903 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Los inicios del cine sonoro y la creación de nuevas empresas fílmicas en México (1928-1931) Mtra. Rosario Vidal Bonifaz Centro Universitario de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Universidad de Guadalajara E-mail: [email protected] Recibido: Septiembre 9, 2007. Aceptado: Diciembre 7, 2007 RESUMEN El cine como industria tuvo su plataforma en las primeras décadas del siglo XX, y la imagen fue su principal elemento de identidad. No será hasta la crisis de 1929 y la necesidad de financiamiento que los empresarios voltean su mirada a la integración de la imagen con el sonido. Surge así el cine sonoro, no exento de temores y recelos empresariales. En México, la historia de la industria cinematográfica es paradójica: se instituye antes de contar con una plataforma sólida. Es bajo la protección del Estado —y su discurso nacionalista— que los empresarios “arriesgan su capital” para el desarrollo del cine.