A Genealogy of the Music Mockumentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spinal Tap, in Which He Performed As the Musician 5 Derek Smalls

Case 2:16-cv-07733 Document 1 Filed 10/17/16 Page 1 of 17 Page ID #:1 1 Peter L. Haviland (Bar Number 144967) [email protected] 2 Scott S. Humphreys (Bar Number 298021) [email protected] 3 Terrence M. Jones (Bar Number 256603) [email protected] 4 BALLARD SPAHR LLP 2029 Century Park East, Suite 800 5 Los Angeles, CA 90067-2909 Telephone: 424.204.4400 6 Facsimile: 424.204.4350 7 Attorneys for Plaintiff Century of Progress Productions 8 9 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 10 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 11 12 CENTURY OF PROGRESS ) Case No. 2:16-cv-07733 PRODUCTIONS, ) 13 ) Plaintiff, ) COMPLAINT FOR: 14 ) ) (1) Breach of Contract; v. ) 15 ) (2) Breach of the Implied Covenant 16 VIVENDI S.A.; STUDIOCANAL; ) of Good Faith and Fair Dealing; ) (3) Fraud; STUDIOCANAL IMAGE; ) 17 RON HALPERN, an individual; and (4) Accounting; and DOES 1 through 10, inclusive, ) 18 ) (5) Declaratory Relief Re: ) Trademark (28 U.S.C. § 2201) ) 19 Defendants. ) ) DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL 20 Deadline) 21 ) 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 COMPLAINT AND DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Case 2:16-cv-07733 Document 1 Filed 10/17/16 Page 2 of 17 Page ID #:2 1 PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 2 1. Harry Shearer, creator of the radio and podcast program "Le Show," 3 and voice of some twenty-three characters on "The Simpsons," is co-creator of 4 the movie classic This Is Spinal Tap, in which he performed as the musician 5 Derek Smalls. 6 2. This Is Spinal Tap and its music, which Shearer also co-wrote, 7 including such songs as "Sex Farm" and "Stonehenge," have remained popular for 8 more than thirty years, and have earned considerable sums for the French 9 conglomerate Vivendi S.A. -

Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2014 Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College Recommended Citation Hernandez, Dahnya Nicole, "Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960" (2014). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 60. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/60 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUNNY PAGES COMIC STRIPS AND THE AMERICAN FAMILY, 1930-1960 BY DAHNYA HERNANDEZ-ROACH SUBMITTED TO PITZER COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE FIRST READER: PROFESSOR BILL ANTHES SECOND READER: PROFESSOR MATTHEW DELMONT APRIL 25, 2014 0 Table of Contents Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................................................2 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................3 Chapter One: Blondie.....................................................................................................................................18 Chapter Two: Little Orphan Annie............................................................................................................35 -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Doc Nyc Announces Final Titles Including

DOC NYC ANNOUNCES FINAL TITLES INCLUDING WORLD PREMIERE OF BRUCE SPRINGSTREEN & THE E STREET BAND’S “DARKNESS ON THE EDGE OF TOWN” CONCERT FILM AT ZIEGFELD THEATER ON NOVEMBER 4TH AND “MOMENTS OF TRUTH” FEATURING ALEC BALDWIN AND OTHER FAMOUS FIGURES DISCUSSING THEIR FAVORITE DOC MOMENTS New York, NY, October 19th 2010 - DOC NYC, New York’s Documentary Festival, announced its final slate of titles including the world premiere of “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” a new concert film with Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band performing their classic album. The film will screen at the Ziegfeld Theatre on November 4. Directed by the Grammy and Emmy award winner Thom Zimny, the film was shot last year at the Paramount Theatre in Asbury Park, NJ in an unconventional manner without any audience in attendance. Springsteen’s manager Jon Landau has said this presentation “best captures the starkness of the original album.” The film will be released on DVD as part of the box set “The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story” later in November. “We wanted to give fans a one night only opportunity to see this spectacular performance on the Ziegfeld’s big screen,” said DOC NYC Artistic Director Thom Powers. A portion of the proceeds from this screening will be donated to the Danny Fund/Melanoma Research Alliance – a non-profit foundation devoted to advancing melanoma research and awareness set up after the 2008 passing of Danny Federici, longtime Springsteen friend and E-Street Band member. DOC NYC will help launch a new promo campaign of shorts called “Moments of Truth,” in which noteworthy figures (actors, politicians, musicians, etc) describe particular documentary moments that moved them. -

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

Screwball Syll

Webster University FLST 3160: Topics in Film Studies: Screwball Comedy Instructor: Dr. Diane Carson, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course focuses on classic screwball comedies from the 1930s and 40s. Films studied include It Happened One Night, Bringing Up Baby, The Awful Truth, and The Lady Eve. Thematic as well as technical elements will be analyzed. Actors include Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, Clark Gable, and Barbara Stanwyck. Class involves lectures, discussions, written analysis, and in-class screenings. COURSE OBJECTIVES: The purpose of this course is to analyze and inform students about the screwball comedy genre. By the end of the semester, students should have: 1. An understanding of the basic elements of screwball comedies including important elements expressed cinematically in illustrative selections from noteworthy screwball comedy directors. 2. An ability to analyze music and sound, editing (montage), performance, camera movement and angle, composition (mise-en-scene), screenwriting and directing and to understand how these technical elements contribute to the screwball comedy film under scrutiny. 3. An ability to apply various approaches to comic film analysis, including consideration of aesthetic elements, sociocultural critiques, and psychoanalytic methodology. 4. An understanding of diverse directorial styles and the effect upon the viewer. 5. An ability to analyze different kinds of screwball comedies from the earliest example in 1934 through the genre’s development into the early 40s. 6. Acquaintance with several classic screwball comedies and what makes them unique. 7. An ability to think critically about responses to the screwball comedy genre and to have insight into the films under scrutiny. -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. For The Economistt perpetuating the Patent Office myth, see April 13, 1991, page 83. 2. See Sass. 3. Book publication in 1906. 4.Swirski (2006). 5. For more on eliterary critiques and nobrow artertainment, see Swirski (2005). 6. Carlin, et al., online. 7. Reagan’s first inaugural, January 20, 1981. 8. For background and analysis, see Hess; also excellent study by Lamb. 9. This and following quote in Conason, 78. 10. BBC News, “Obama: Mitt Romney wrong.” 11. NYC cabbies in Bryson and McKay, 24; on regulated economy, Goldin and Libecap; on welfare for Big Business, Schlosser, 72, 102. 12. For an informed critique from the perspective of a Wall Street trader, see Taleb; for a frontal assault on the neoliberal programs of economic austerity and political repression, see Klein; Collins and Yeskel; documentary Walmart. 13. In Kohut, 28. 14. Orwell, 318. 15. Storey, 5; McCabe, 6; Altschull, 424. 16. Kelly, 19. 17. “From falsehood, anything follows.” 18. Calder; also Swirski (2010), Introduction. 19. In The Economist, February 19, 2011: 79. 20. Prominently Gianos; Giglio. 21. The Economistt (2011). 22. For more examples, see Swirski (2010); Tavakoli-Far. My thanks to Alice Tse for her help with the images. Chapter 1 1. In Powers, 137; parts of this research are based on Swirski (2009). 2. Haynes, 19. 168 NOTES 3. In Moyers, 279. 4. Ruderman, 10. 5. In Krassner, 276–77. 6. Green, 57; bottom of paragraph, Ruderman, 179. 7. In Zagorin, 28; next quote 30; Shakespeare did not spare the Trojan War in Troilus and Cressida. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Nomination Press Release Outstanding Character Voice-Over Performance F Is For Family • The Stinger • Netflix • Wild West Television in association with Gaumont Television Kevin Michael Richardson as Rosie Family Guy • Con Heiress • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin, Stewie Griffin, Brian Griffin, Glenn Quagmire, Tom Tucker, Seamus Family Guy • Throw It Away • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television Alex Borstein as Lois Griffin, Tricia Takanawa The Simpsons • From Russia Without Love • FOX • Gracie Films in association with 20th Century Fox Television Hank Azaria as Moe, Carl, Duffman, Kirk When You Wish Upon A Pickle: A Sesame Street Special • HBO • Sesame Street Workshop Eric Jacobson as Bert, Grover, Oscar Outstanding Animated Program Big Mouth • The Planned Parenthood Show • Netflix • A Netflix Original Production Nick Kroll, Executive Producer Andrew Goldberg, Executive Producer Mark J. Levin, Executive Producer Jennifer Flackett, Executive Producer Joe Wengert, Supervising Producer Ben Kalina, Supervising Producer Chris Prynoski, Supervising Producer Shannon Prynoski, Supervising Producer Anthony Lioi, Supervising Producer Gil Ozeri, Producer Kelly Galuska, Producer Nate Funaro, Produced by Emily Altman, Written by Bryan Francis, Directed by Mike L. Mayfield, Co-Supervising Director Jerilyn Blair, Animation Timer Bill Buchanan, Animation Timer Sean Dempsey, Animation Timer Jamie Huang, Animation Timer Bob's Burgers • Just One Of The Boyz 4 Now For Now • FOXP •a g2e0 t1h Century -

Click to Download

v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Action Back In Bond!? pg. 18 MeetTHE Folks GUFFMAN Arrives! WIND Howls! SPINAL’s Tapped! Names Dropped! PLUS The Blue Planet GEORGE FENTON Babes & Brits ED SHEARMUR Celebrity Studded Interviews! The Way It Was Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, MARVIN HAMLISCH Annette O’Toole, Christopher Guest, Eugene Levy, Parker Posey, David L. Lander, Bob Balaban, Rob Reiner, JaneJane Lynch,Lynch, JohnJohn MichaelMichael Higgins,Higgins, 04> Catherine O’Hara, Martin Short, Steve Martin, Tom Hanks, Barbra Streisand, Diane Keaton, Anthony Newley, Woody Allen, Robert Redford, Jamie Lee Curtis, 7225274 93704 Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Wolfman Jack, $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada JoeJoe DiMaggio,DiMaggio, OliverOliver North,North, Fawn Hall, Nick Nolte, Nastassja Kinski all mentioned inside! v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c2 On August 19th, all of Hollywood will be reading music. spotting editing composing orchestration contracting dubbing sync licensing music marketing publishing re-scoring prepping clearance music supervising musicians recording studios Summer Film & TV Music Special Issue. August 19, 2003 Music adds emotional resonance to moving pictures. And music creation is a vital part of Hollywood’s economy. Our Summer Film & TV Music Issue is the definitive guide to the music of movies and TV. It’s part 3 of our 4 part series, featuring “Who Scores Primetime,” “Calling Emmy,” upcoming fall films by distributor, director, music credits and much more. It’s the place to advertise your talent, product or service to the people who create the moving pictures. -

Catalogue Festival International Ciné

sommaire / summary PRÉSENTATION GÉNÉRALE PRESENTATION GENERALE 48 Monstres / Monsters 3 Sommaire / Summary 51 Soirée courts métrages « Attaque des PsychoZombies » / 4 Editos / Forewords "PsychoZombies’ Attack" short films night 12 Jurys officiels / Official juries 16 Invités / Guests 18 Cérémonies d'ouverture et de palmarès / Opening and HOMMAGE ANIME AU STUDIO GHIBLI palmares ceremonies 52 Conférence / Conference 20 Fête des enfants / Kids party 52 Rétrospective Studio Ghibli / Retrospective 55 Exposition - « Hayao Miyazaki en presse » / Exhibition COMPETITIONS INTERNATIONALES 22 Longs métrages inédits / Unreleased feature films AUTOUR DES FILMS 32 Courts métrages ados / Teenager short films 56 Séminaire « Les outils numériques dans l’éducation à 34 Courts métrages d'animation / Short animated films l’image » / Seminar 57 Ateliers et animations / Workshops and activities 60 Rencontres et actions éducatives / Meetings and educational INEDITS ET AVANT-PREMIERES HORS actions COMPETITION 65 Décentralisation / Decentralization 38 Ciné-bambin / Toddlers film 38 Séances scolaires et familles / School and family screenings 43 Séances scolaires et ado-adultes / Youth and adults screenings INFOS PRATIQUES 66 Equipe et remerciements / Team and thanks 68 Contacts / Print sources THEMATIQUE «CINEMA FANTASTIQUE» 70 Lieux du festival / Venues 44 Ciné-concert / Concert film 72 Réservations et tarifs / Booking and prices 45 Robots et mondes futuristes / Robots and futuristic worlds 74 Grille programme à Saint-Quentin / Schedule in Saint-Quentin 46 Magie, contes et mondes imaginaires / Magic, tales and 78 Index / Index imaginary worlds 79 Partenaires / Partnerships and sponsors éditos / foreword Une 33ème édition sous le Haut-Patronage de Madame Najat VALLAUD- BELKACEM, Ministre de l'éducation nationale, de l'enseignement supérieur et de la recherche. Ciné-Jeune est fantastique ! L’édition 2015 du Festival s’est donné pour thème le « Cinéma fantastique ». -

A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form. Ralph Randolph Duncan II Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Panel Analysis: A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form. Ralph Randolph Duncan II Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Duncan, Ralph Randolph II, "Panel Analysis: A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4910. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4910 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The qualityof this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copysubmitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

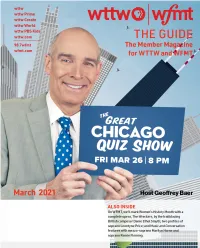

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili.