A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form. Ralph Randolph Duncan II Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Grown-Ups Are Dumb by Alexa Kitchen Grown-Ups Are Dumb by Alexa Kitchen

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Grown-Ups are Dumb by Alexa Kitchen Grown-Ups are Dumb by Alexa Kitchen. Bibliographic record and links to related information available from the Library of Congress catalog. Information from electronic data provided by the publisher. May be incomplete or contain other coding. Dumb parents, little brothers, gigantic messes, and homework--this is the plight of young readers everywhere. And, until now, it had not been expressed by someone so close to the source. Ten-year-old Alexa Kitchen may have an unusual talent--she is the world's youngest comics artist--but she really is just like many girls her age. Just trying to get by in a world that seems determined to undermine her at every turn. Luckily she's got a way with a pen and a good sense of humor. This collection of funny, insightful cartoons based on the real-life trials of many families will resonate with young readers everywhere. Library of Congress subject headings for this publication: Preteens -- Comic books, strips, etc. Girls -- Comic books, strips, etc. Cartoons and comics. Grown-Ups are Dumb by Alexa Kitchen. Bibliographic record and links to related information available from the Library of Congress catalog. Biographical text provided by the publisher (may be incomplete or contain other coding). The Library of Congress makes no claims as to the accuracy of the information provided, and will not maintain or otherwise edit/update the information supplied by the publisher. 1423113317 03. Ten-year-old Alexa Kitchen may have an unusual talent--she is the world's youngest comics artist--but she really is just like many girls her age. -

ROY THOMAS Chapter Four

Captain Marvel Jr. TM & © DC Comics DC © & TM Jr. Marvel Captain Introduction by ROY THOMAS Chapter Four Little Boy Blue Ed Herron had come to Fawcett with a successful track record of writing Explosive is the best way to describe this iconic, colorful cover (on opposite page) by and creating comic book characters that had gone on to greater popularity, Mac Raboy, whose renditions of a teen-age super-hero with a realistic physique was noth- including work on the earliest stories of Timely’s colorful Captain America— ing less than perfect. Captain Marvel Jr. #4, (Feb. 19, 1943). Inset bottom is Raboy’s first and his kid sidekick Bucky. It was during the fall of 1941 that Herron came cover for Fawcett and the first of the CMJr origin trilogy, Master Comics #21 (Dec. 1941). Below up with the idea of a new addition to the Fawcett family. With Captain is a vignette derived from Raboy’s cover art for Captain Marvel Jr. #26 (Jan. 1, 1945). Marvel sales increasing dramatically since his debut in February 1940, Fawcett management figured a teenage version of the “Big Red Cheese” would only increase their profits. Herron liked Raboy’s art very much, and wanted a more illustrative style for the new addition, as opposed to the C. C. Beck or Pete Costanza simplified approach on Captain Marvel. The new boy-hero was ably dubbed Captain Marvel Jr., and it was Mac Raboy who was given the job of visualizing him for the very first time. Jr.’s basic attire was blue, with a red cape. -

Downloadable Content, and Other Low-Cost Con-Themed Items Provide Similar Experiences

Nova Southeastern University From the SelectedWorks of Jon M. Garon 2017 Pop Culture Business Handbook for Cons and Festivals: Introduction and Introduction and Table of Contents Jon M. Garon Available at: https://works.bepress.com/ jon_garon/49/ FILM FESTIVALS, COMIC CONVENTIONS, MUSIC FESTIVALS AND CULTURAL EVENTS DOMINATE THE MODERN CULTURAL LANDSCAPE. EVERY ATTENDEE, VENDOR, EXHIBITOR, PANELIST, AND ORGANIZER NEEDS A PLAYERS HANDBOOK TO NAVIGATE THE RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLDS OF CONS AND FESTIVALS. Pop Culture Business Handbook for Cons and Fes vals provides a real-world guide and reference for these exhilara ng experiences, providing rules, strategies, and insights for the people who a end, work, and develop these fantas cal worlds. With discussions on cosplay, selling autographs, film fes val submissions, organizing panels, policing bootlegs as well as insurance, crowdfunding, budge ng, pyrotechnics, safety and Con planning, the Handbook provides the defini ve guide to “Con Law.” It is an essen al planning tool for any road trip for a conven on and a must for anyone launching or managing a Con or fes val. Advance praise for Pop Culture Business Handbook for Cons and Fes vals “DO NOT HOST NERDS WITHOUT READING THIS BOOK! Anyone who cares about fandom, conven ons, gamifica on, making money and following the law must read this book cover to cover.” - Theodore F. Claypoole, Partner at Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice, LLP "Cons are no longer just events; they are full-fledged businesses requiring professional planning, management and legal compliance. … The book includes extremely useful G guidelines for successfully organizing Cons, mi ga ng risks, and achieving planned outcomes." a r - Dr. -

Arbor House Assisted Living 4501 W

JULY 2017 Arbor House Assisted Living 4501 W. Main Norman, OK 73072 Arbor House Anything but Conventional It’s the ultimate event for any fan of comics and entertainment, costume parties and celebrity sightings: July 19–23 is 2017’s Comic-Con International. This fan convention is the biggest of its kind in the world, and in many ways the fans provide the biggest show. People Our Staff are encouraged to show up wearing elaborate costumes of their favorite comic book, television, film, or book Christi Dobbs characters. You’ll likely see the Incredible Hulk mingling Executive Director with Jedi Knights, Harry Potter, and characters from the Marki Denton sitcom The Big Bang Theory. This eclectic mix is Comic- Director of Nursing Con’s signature achievement, bringing fans of all ages and interests together to “geek out” over their favorite Lillian “Lil” Kenney popular entertainment. Admissions & Marketing Director Self-described “geeks” have been flocking to San Diego Sarah Dixon for Comic-Con since 1970, when Shel Dorf, Richard Alf, Feeling Bullish July Birthdays Dietary Supervisor Ken Krueger, Marvin Nelson, Mike Towry, Barry Alphonso, Bob Sourk, and Greg Bear founded the Golden State Nina Nichols Most everyone has heard RESIDENTS Engagement Coordinator Comic Book Convention. The original event drew only of Pamplona’s notorious 300 people, but it was a mecca for all things comic Encerrio, or “Running of the June D – 7/15 Laura Tucker related. Over the years, the scope of the production Bulls.” Lesser known is the Administrative Assistant grew along with the size of the convention crowds. -

COLORS and MOODS White Paper

COLORS AND MOODS Susan Minamyer, M.A. in Psychology Roosevelt University Scientists have studied the effect of color determined the accuracy of these on our mood and way of thinking for associations with an international many years. Since the time of Pavlov and database of over 60,000 individuals. his experiments with salivating dogs, In addition to mental associations, there psychologists have known that stimuli can are also physical responses to color. Light take on the properties of other stimuli energy stimulates the pituitary and penal with which they are associated. Pavlov glands, and these regulate hormones and used a bell and some meat; current our bodies’ other physiological systems. theorists are focusing on colors and the Red, for example, stimulates, excites and moods with which they are associated. warms the body, increases the heart rate, brain wave activity, and respiration Since everyone has different experiences, (Friedman). there will be some variability of associations to colors. There also are Bright colors, such as yellow, reflect more some correlations that are specific to light and stimulate the eyes. Yellow is the particular cultures. However, there are color that the eye processes first, and is also universal associations that are the most luminous and visible color in the applicable to nearly everyone. There is spectrum. There may be effects from surprising consistency among authors colors that we do not even understand who describe these associations. yet. Neuropsychologist Kurt Goldstein (Eiseman, Holtschue, McCauley, Morton) found that a blindfolded person will Because of its association with nature and experience physiological reactions under vegetation, green is associated with rays of different colors. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

Media Website Contact List

MEDIA WEBSITE CONTACT LIST version: 8/2016 Outlet Name First Name Last Name Title Email Address Website Address Bleeding Cool Richard Johnston Editor-in-Chief [email protected] http://www.bleedingcool.com/ Comics Alliance Andrew Wheeler Editor in Chief [email protected] http://comicsalliance.com/ Comics Alliance Kevin Gaussoin Editor in Chief [email protected] http://comicsalliance.com/ Comic Book Resources Albert Ching Managing Editor [email protected] http://www.comicbookresources.com/ Comic Vine Tony Guerrero Editor-in-Chief [email protected] http://www.comicbookresources.com/ ComicBook.com James Viscardi Editor in Chief [email protected] http://comicbook.com/ Forces of Geek Erin Maxwell Reporter [email protected] http://www.forcesofgeek.com/ IGN Entertainment Joshua Yehl Comics Editor [email protected] http://www.ign.com/ ICV2 Milton Griepp Editor in Chief [email protected] http://icv2.com/ Newsarama Chris Arrant Editor-in-Chief [email protected] http://www.newsarama.com/ The Beat Heidi MacDonald Editor in Chief [email protected] http://www.comicsbeat.com/ Comicosity Matt Santori-Griffith Senior Editor [email protected] http://www.comicosity.com/ The Mary Sue Maddy Myers Editor [email protected] http://www.themarysue.com/ The Mary Sue Dan Van Winkle Editor [email protected] http://www.themarysue.com/ Multiversity Comics Brian Salvatore Editor-in-Chief [email protected] http://multiversitycomics.com/ Comic Crusaders [email protected] www.comiccrusaders.com/ Graphic Policy Brett Schenker Founder / Blogger in Chief [email protected] https://graphicpolicy.com/ THIS LIST OF CONTACTS IS DESIGNED TO BE A RESOURCE FOR PUBLISHERS TO HELP PROMOTE THEIR PROJECTS TO THE PUBLIC. -

Jnt£Rnationa1 Journal of Comic Art

JNT£RNATIONA1 JOURNAL OF COMIC ART Vol. 14, No. 1 Spring2012 112 113 Graphic Tales of Cancer catharsis, testimonies, and education. Michael Rhode and JTH Connor1 Cartoons, Comics, Funnies, Comic Books "Cancer is not a single disease," said Robert A. Weinberg, a cancer While names work against it, and demagogues have railed against it, biologist at the Whitehead Institute and the Massachusetts Institute comic art has not necessarily been for children. 8 And cancer is not the only of Technology. "It's really dozens, arguably hundreds of diseases."' illness seen in comic art-- characters have died of AIDS in the "Doonesbury" comic strip and the Incredible Hulk comic book, and survived AIDS in Peeter's autobiographical Blue Pills; "Doonesbury"'s football-star-turned-coach B.D. Few people in North America are unaware of or unaffected by the popular suffered a traumatic amputation of his leg in Iraq; "Crankshaft" coped with and professional publicity related to the incidences of the various forms of Alzheimer's disease; Frenchman David B. cartooned a graphic novel on his cancer, the search for a "cure for cancer," the fund-raising runs and other brother's epilepsy; Haidee Merritt drew gag cartoons about her diabetes; similar campaigns in support of research into its causes and treatment, or the "Ziggy"'s Tom Wilson wrote a prose book on his depression, and Keiko To be pink-looped ribbon that is immediately identifiable as the "logo" for breast won awards for her 14-volume fictional manga about autism. 9 Editorial cancer awareness. Study of the history of cancer through professional medical cartoonists have long addressed the link between tobacco use and cancer, 10 and surgical literature is an obvious and traditional portal to understanding as did Garry Trudeau who has long opposed smoking as seen in his Mr. -

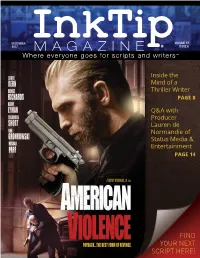

MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where Everyone Goes for Scripts and Writers™

DECEMBER VOLUME 17 2017 MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers™ Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer PAGE 8 Q&A with Producer Lauren de Normandie of Status Media & Entertainment PAGE 14 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! CONTENTS Contest/Festival Winners 4 Feature Scripts – FIND YOUR Grouped by Genre SCRIPTS FAST 5 ON INKTIP! Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer 8 INKTIP OFFERS: Q&A with Producer Lauren • Listings of Scripts and Writers Updated Daily de Normandie of Status Media • Mandates Catered to Your Needs & Entertainment • Newsletters of the Latest Scripts and Writers 14 • Personalized Customer Service • Comprehensive Film Commissions Directory Scripts Represented by Agents/Managers 40 Teleplays 43 You will find what you need on InkTip Sign up at InkTip.com! Or call 818-951-8811. Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they place their scripts on our site. 3 WHAT PEOPLE SAY ABOUT INKTIP WRITERS “[InkTip] was the resource that connected “Without InkTip, I wouldn’t be a produced a director/producer with my screenplay screenwriter. I’d like to think I’d have – and quite quickly. I HAVE BEEN gotten there eventually, but INKTIP ABSOLUTELY DELIGHTED CERTAINLY MADE IT HAPPEN WITH THE SUPPORT AND FASTER … InkTip puts screenwriters into OPPORTUNITIES I’ve gotten through contact with working producers.” being associated with InkTip.” – ANN KIMBROUGH, GOOD KID/BAD KID – DENNIS BUSH, LOVE OR WHATEVER “InkTip gave me the access that I needed “There is nobody out there doing more to directors that I BELIEVE ARE for writers than InkTip – nobody. -

Motion and Color Cognition

Encyclopedia of Color Science and Technology DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-27851-8_63-8 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 Motion and Color Cognition Donald Hoffman* Department of Cognitive Sciences, University of California at Irvine, Irvine, CA, USA Synonyms Achromatopsia; Color from motion; Dynamic color spreading; Neon color spreading Definition Motion and color cognition is a branch of cognitive neuroscience devoted to using brain imaging, psychophysical experiments, and computational modeling to understand the interactions between motion and color processing in the human visual system. Overview The relationships between the perceptions of color and visual motion are complex and intriguing. Evidence from patients with certain rare forms of damage to the cerebral cortex indicates that color and motion are to some extent processed separately within the visual system. This conclusion is buttressed by physiological evidence for separate neural pathways for the processing of color and motion and psychophysical evidence that the perception of motion in color displays is greatly reduced when the colors are isoluminant. However, experiments and demonstrations reveal that the perceptions of color and motion can interact. Motion can trigger the perception of color in achromatic stimuli and in uncolored regions of space. Color can determine the perceived direction of motion, and changes in color can trigger the perception of apparent motion. This article briefly reviews the evidence for separate processing of color and visual motion and for the ways they interact. Evidence for Separate Processing of Color and Motion Patients with the rare condition of cerebral achromatopsia cannot perceive colors, due to damage of cortex in the inferior temporal lobe of both cerebral hemispheres [1, 2].