The Socialist Movement in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"The Pioneers of the Great Army of Democrats": the Mythology and Popular History of the British Labour Party, 1890-193

"The Pioneers of the Great Army of Democrats": The Mythology and Popular History of the British Labour Party, 1890-1931 TAYLOR, Antony <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4635-4897> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/17408/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version TAYLOR, Antony (2018). "The Pioneers of the Great Army of Democrats": The Mythology and Popular History of the British Labour Party, 1890-1931. Historical Research, 91 (254), 723-743. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk ‘The Pioneers of the Great Army of Democrats’: The Mythology and Popular History of the British Labour Party, 1890-1931 Recent years have seen an increased interest in the partisan uses of the political past by British political parties and by their apologists and adherents. This trend has proved especially marked in relation to the Labour party. Grounded in debates about the historical basis of labourism, its ‘true’ nature, the degree to which sacred elements of the past have been discarded, marginalised, or revived as part of revisions to the labour platform and through changes of leader, the past has become a contentious area of debate for those interested in broader currents of reform and their relationship to the progressive movements that fed through into the platform of the early twentieth-century Labour party. Contesting traditional notions of labourism as an undifferentiated and unimaginative creed, this article re-examines the political traditions that informed the Labour platform and traces the broader histories and mythologies the party drew on to establish the basis for its moral crusade. -

File Is Composed of the Comfortable Class

The English Radical Tradition and the British Left 1885-1945 ENDERBY, John Stephen Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26096/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26096/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. The English Radical Tradition and the British Left 1885-1945 by John Stephen Enderby A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 I hereby declare that: 1. I have not been enrolled for another award of the University, or other academic or professional organisation, whilst undertaking my research degree. 2. None of the material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award. 3. I am aware of and understand the University's policy on plagiarism and certify that this thesis is my own work. The use of all published or other sources of material consulted have been properly and fully acknowledged. 4. The work undertaken towards the thesis has been conducted in accordance with the SHU Principles of Integrity in Research and the SHU Research Ethics Policy. -

Literature and the Late-Victorian Radical Press

Literature Compass 7/8 (2010): 702–712, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00729.x Literature and the Late-Victorian Radical Press Elizabeth Carolyn Miller* University of California, Davis Abstract Amidst a larger surge in the number of books and periodicals published in late-nineteenth-century Britain, a corresponding surge occurred in the radical press. The counter-cultural press that emerged at the fin de sie`cle sought to define itself in opposition to commercial print and the capitalist press and was deeply antagonistic to existing political, economic, and print publishing structures. Litera- ture flourished across this counter-public print sphere, and major authors of the day such as William Morris and George Bernard Shaw published fiction, poetry, and literary criticism within it. Until recently, this corner of late-Victorian print culture has been of interest principally to historians, but literary critics have begun to take more interest in the late-Victorian radical press and in the literary cultures of socialist newspapers and journals such as the Clarion and the New Age. Amidst a larger surge in the number of books and periodicals published in Britain at the end of the nineteenth century, a corresponding surge occurred in the radical press: as Deian Hopkin calculates, several hundred periodicals representing a wide array of socialist perspectives were born, many to die soon after, in the decades surrounding the turn of the century (226). An independent infrastructure of radical presses, associated with various radical organizations and editors, emerged as an alternative means of periodical production apart from commercial, profit-oriented print.1 Literature and literary discourse flourished across this counterpublic sphere, and major authors of the day published fiction, poetry, and journalism within it: in the 1880s, for example, William Morris spent five years editing and writing for the revolutionary paper Commonweal, while George Bernard Shaw cut his teeth as an author by serializing four novels in the socialist journals To-Day and Our Corner. -

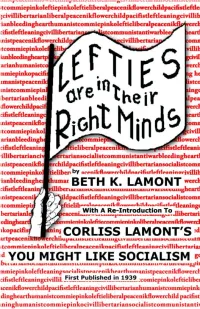

LEFTIES ARE in THEIR RIGHT MINDS Part One

LEFTIES ARE IN THEIR RIGHT MINDS LEFTIES ARE IN THEIR RIGHT MINDS Part One By Beth K. Lamont April 2009 And A Re-Introduction to Corliss Lamont’s You Might Like Socialism First Published in 1939 HALF-MOON FOUNDATION, INC. The Half-Moon Foundation was formed to promote enduring inter- national peace, support for the United Nations, the conservation of our country’s natural environment, and to safeguard and extend civil liberties as guaranteed under the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Lefties Are In Their Right Minds Copyright © 2009 by Beth K. Lamont All rights reserved. Published by Half-Moon Foundation, Inc. ISBN 978-0-578-00782-3 You Might Like Socialism: A Way of Life for Modern Man Copyright © 1939 by Corliss Lamont Originally published by Modern Age Books, Inc. New York, NY Visit the Corliss Lamont Web site http://www.corliss-lamont.org/ Printed in the United States of America Preface Actually, there’s no need for you to read this book at all! The title sums up its whole thesis. When I say Lefties Are In Their Right Minds, I’m trying to give a whimsical approach to a very serious subject. The Righties of this world, who still believe that their might makes them right, have been wrong for too long. That’s why I’m urging: Lefties, it’s you who are right! Check-out a true Leftie-Life-Line: Pacifica Radio, especially its New York Station, @ FM 99.5 WBAI! We're gathering strength! We need to Unite! And what perfect timing. Unbridled Capitalism is in disgrace; I picture rowdy, irresponsible teenagers behaving badly and Big Daddy having to bail them out of jail. -

The Socialist Macro-Sect in the ‘Digital Age’: the Victorian Socialists’ Strategy for Assembling a Counterpublic

tripleC 18 (2): 685-700, 2020 http://www.triple-c.at The Socialist Macro-Sect in the ‘Digital Age’: The Victorian Socialists’ Strategy for Assembling a Counterpublic By Ian Anderson RMIT, Melbourne, Australia, [email protected], jetpack.zoob.net Abstract: The Victorian Socialists (VicSocialists) are a socialist electoral organisation in Aus- tralia which has had some electoral success as a regional fourth party behind the Greens. This article seeks to address what kind of organisation the VicSocialists are, what communi- cative techniques the organisation employs in assembling a counterpublic or constituency, and what this case study illustrates in terms of the broader formation of counterpublics in the ‘digital age’. This article characterises the VicSocialists as a “macro-sect”, a new organisa- tional form. The macro-sect is something more than a socialist micro-sect and less than a mass party, while optimistically conceiving of itself as a proto-mass party. The macro-sect strategy is distinct from another 21st-century party-form, the digital party. Unlike the digital parties, which tend to fetishise digital media, the VicSocialists treat digital media soberly as just one tool in the formation and mobilisation of counterpublics, a tool with serious limita- tions. Additionally, digital media is complementary with face-to-face communication (such as doorknocking) in important ways. A study of a parallel US macro-sect, the DSA, similarly found that activists were ambivalent about digital media, yet strongly used it for promotion. This commonality with the DSA suggests the international emergence of a new organisation- al form, with a distinct communicative strategy for forming counterpublics in the so-called ‘digital age’ – one which necessarily uses digital media, yet does not fetishise it. -

Phemister2017.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. ‘Our American Aristotle’ Henry George and the Republican Tradition during the Transatlantic Irish Land War, 1877-1887 Andrew Phemister PhD University of Edinburgh 2016 Abstract This thesis examines the relationship between Henry George and the Irish on both sides of the Atlantic and, detailing the ideological interaction between George’s republicanism and Irish nationalism, argues that his uneven appeal reveals the contours of the construction of Gilded Age Irish-America. The work assesses the functionality and operation, in both Ireland and the US, of Irish culture as a dynamic but discordant friction within the Anglophone world. Ireland’s unique geopolitical position and its religious constitution nurtured an agrarianism that shared its intellectual roots with American republicanism. This study details how the crisis of Irish land invigorated both traditions as an effective oppositional culture to the processes of modernity. -

Tribune BACK COPIES Attention Libraries, Schools and Tertiary Institutions!

Tribune BACK COPIES Attention libraries, schools and tertiary institutions! T w er ly oac.K co pies of h LH, dating from May 1978, .ire available as a set for $18.00. Single copies are aiso available; Numbers 70-90 52 Earlier editions $1. All post free. Write to ALR. PO Box A247, Sydney South 2000. In its 60 years, Tribune has been illegal, praised, quoted, raided, Spring 1983, No. 85, Kimberley Land Rights* daily, sued, abused, searched, Melal Industry crisis • US copied, busted...but we have never bases • Unemployment in been silenced. the 1930s • $2. In the last few months Tribune has carried interviews with arms expert Andrew Mack on the disarmament talks, NDP senator Jo Vallentine. political economist Ted Wheelwright, singers Margret RoadKnight, Jeannie Lewis and Robyn Archer, playwright Stephen Sewell, the Women's Housing Company, Shorty O'Neill from the National Federation of Land Councils and many others. Summer 1983, No. 86, Life If you want a genuinely broad left under Labor** Philippines Eurocommunism • Land weekly newspaper, you can t be left Rights • Reviews • $2. without it. Autumn 1984. No. 87, Organised crim e in NSW Uranium and Labor • Subscribe! Interview with Noel Counihan • $2. Subscription rales: Two years $45, One year $2K, Six months $15, three months S8. Institutions S35. Students, pensioners, unemployed: One year SIS, Six months SKI, three months $6. Prisoners free. I enclose S .................. for subscription. ittw* .* * »■ « ■ -r^mrwm +**d I jfc.w Name: \ddrev»: ........................................................................... Winter 1984, No. B8, Nicaragua • The Accord • ............................. ............ ..................... Post code Feminist Strategies * Issues for working parents Bank card No. -

The Undiscovered Country: Essays In

T H E UNDISCOVERED COUNTRY Cultural Dialectics series editor: Raphael Foshay The difference between subject and object slices through subject as well as through object. theodore adorno Cultural Dialectics provides an open arena in which to debate questions of cul- ture and dialectic — their practices, their theoretical forms, and their relations to one another and to other spheres and modes of inquiry. Approaches that draw on any of the following are especially encouraged: continental philoso- phy, psychoanalysis, the Frankfurt and Birmingham schools of cultural theory, deconstruction, gender theory, postcoloniality, and interdisciplinarity. series titles Northern Love: An Exploration of Canadian Masculinity Paul Nonnekes Making Game: An Essay on Hunting, Familiar Things, and the Strangeness of Being Who One Is Peter L. Atkinson Valences of Interdisciplinarity: Theory, Pedagogy, Practice Edited by Raphael Foshay Imperfection Patrick Grant The Undiscovered Country: Essays in Canadian Intellectual Culture Ian Angus T H E UNDISCOVERED COUNTRY E S S AY S I N CANADIAN INTELLECTUAL CuLtuRE IAN ANGUS Copyright © 2013 Ian Angus Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, AB T5j 3s8 ISBN 978-1 -927356-32-6 (print) 978-1 -927356-33-3 (PDF) 978-1 -927356-34-0 (epub) A volume in Cultural Dialectics ISSN 1915-836X (print) 1915-8378 (digital) Cover and interior design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Book Printers. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Angus, Ian H. (Ian Henderson) The undiscovered country : essays in Canadian intellectual culture / Ian Angus. (Cultural dialectics, ISSN 1915-836X) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Proportional Representation in Theory and Practice the Australian Experience

Proportional Representation in Theory and Practice The Australian Experience Glynn Evans Department of Politics and International Relations School of Social Sciences The University of Adelaide June 2019 Table of Contents Abstract ii Statement of Authorship iii Acknowledgements iv Preface vi 1. Introduction 1 2. District Magnitude, Proportionality and the Number of 30 Parties 3. District Magnitude and Partisan Advantage in the 57 Senate 4. District Magnitude and Partisan Advantage in Western 102 Australia 5. District Magnitude and Partisan Advantage in South Eastern Jurisdictions 132 6. Proportional Representation and Minor Parties: Some 170 Deviating Cases 7. Does Proportional Representation Favour 204 Independents? 8. Proportional Representation and Women – How Much 231 Help? 9. Conclusion 247 Bibliography 251 Appendices 260 i Abstract While all houses of Australian parliaments using proportional representation use the Single Transferable Vote arrangement, district magnitudes (the numbers of members elected per division) and requirements for casting a formal vote vary considerably. Early chapters of this thesis analyse election results in search for distinct patterns of proportionality, the numbers of effective parties and partisan advantage under different conditions. This thesis argues that while district magnitude remains the decisive factor in determining proportionality (the higher the magnitude, the more proportional the system), ballot paper numbering requirements play a more important role in determining the number of (especially) parliamentary parties. The general pattern is that, somewhat paradoxically, the more freedom voters have to choose their own preference allocations, or lack of them, the smaller the number of parliamentary parties. Even numbered magnitudes in general, and six member divisions in particular, provide some advantage to the Liberal and National Parties, while the Greens are disadvantaged in five member divisions as compared to six or seven member divisions. -

Donor to Political Party and Political Campaigner Return Form

Donor to Political Party and Political Campaigner Disclosure Return – Organisations FINANCIAL YEAR 2019-20 Section 305B(1) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Electoral Act) requires donors to furnish a return within 20 weeks after the end of the financial year. The due date for lodging this return is 17 November 2020. Completing the Return: • This return is to be completed by organisations who made a donation to a registered political party (or a State branch), political campaigner, or to another person or organisation with the intention of benefiting a registered political party or political campaigner. • This return is to be completed with reference to the Financial Disclosure Guide for Donors to Political Parties and Political Campaigners. • This return will be available for public inspection from Monday 1 February 2021 at www.aec.gov.au. • Any supporting documentation included with this return may be treated as part of a public disclosure and displayed on the AEC website. • The information on this return is collected under s305B of the Electoral Act. NOTE: This form is for the use of organisations only. Please use the form Donor to Political Party and Political Campaigner Disclosure Return – Individuals if you are completing a return for an individual. Details of organisation that made the donation Name Address Suburb/Town State Postcode ABN ACN Details of person completing this return Name Capacity or position (e.g. company secretary) Postal address Suburb/Town State Postcode Telephone number ( ) Fax number ( ) Email address Certification I certify that the information contained in this return and its attachments is true and complete to the best of my knowledge, information and belief. -

Spring 2020 – Election Feature

North and West Melbourne News SPRING 2020 13 Melbourne City Council Election Key dates: Ballots posted to registered voters – 6-8 October; voting closes – 23 October Melbourne City Council’s place in our world Meg De Young The News and the Centre have assembled three-term President/Mayor at Melton City Council. this 4-page feature to provide voters with “The state makes certain directions, such as Melbourne City Council is the local government information that may help them in the Melbourne capping the percentage increase for rates, body responsible for the municipality of City Council election being held during October. Margaret said. Melbourne. The Council consists of a Lord Mayor, a This information is particularly important “The Council determines its budget according to Deputy Lord Mayor and nine Councillors. this year, when COVID-19 restrictions make what it sees as the community needs. Councillors The Chief Executive Officer liaises with the traditional electioneering, such as public are elected every four years and the majority of meetings, impossible. offices of the Lord Mayor and Deputy Lord Mayor, councils are divided into wards with proportional Councillors, City of Melbourne executives, Victorian representation.” Government and community and corporate MCC provides pre-school, youth support and senior citizens facilities and programs, library Margaret talked about local governments’ stakeholders to see that objectives are being met. responsibilities. “Council is responsible The City of Melbourne municipality covers 14 services and meeting rooms for local groups. It also has a strong role in advocacy with other for providing a wide variety of services and suburbs, including the CBD. -

Portugal and Her Islandy| a Study in Strategic Location

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1977 Portugal and her islandy| A study in strategic location James Elliott Curry The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Curry, James Elliott, "Portugal and her islandy| A study in strategic location" (1977). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3256. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3256 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PORTUGAL AND HER ISLANDS: A STUDY IN STRATEGIC LOCATION by James E. Curry B.A., University of Montana, 1969 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1977 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners De-^k^, G^raduaxe Schoo n Date UMI Number: EP34446 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT UMI EP34446 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author.