File Is Composed of the Comfortable Class

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People, Place and Party:: the Social Democratic Federation 1884-1911

Durham E-Theses People, place and party:: the social democratic federation 1884-1911 Young, David Murray How to cite: Young, David Murray (2003) People, place and party:: the social democratic federation 1884-1911, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3081/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk People, Place and Party: the Social Democratic Federation 1884-1911 David Murray Young A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Durham Department of Politics August 2003 CONTENTS page Abstract ii Acknowledgements v Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1- SDF Membership in London 16 Chapter 2 -London -

"The Pioneers of the Great Army of Democrats": the Mythology and Popular History of the British Labour Party, 1890-193

"The Pioneers of the Great Army of Democrats": The Mythology and Popular History of the British Labour Party, 1890-1931 TAYLOR, Antony <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4635-4897> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/17408/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version TAYLOR, Antony (2018). "The Pioneers of the Great Army of Democrats": The Mythology and Popular History of the British Labour Party, 1890-1931. Historical Research, 91 (254), 723-743. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk ‘The Pioneers of the Great Army of Democrats’: The Mythology and Popular History of the British Labour Party, 1890-1931 Recent years have seen an increased interest in the partisan uses of the political past by British political parties and by their apologists and adherents. This trend has proved especially marked in relation to the Labour party. Grounded in debates about the historical basis of labourism, its ‘true’ nature, the degree to which sacred elements of the past have been discarded, marginalised, or revived as part of revisions to the labour platform and through changes of leader, the past has become a contentious area of debate for those interested in broader currents of reform and their relationship to the progressive movements that fed through into the platform of the early twentieth-century Labour party. Contesting traditional notions of labourism as an undifferentiated and unimaginative creed, this article re-examines the political traditions that informed the Labour platform and traces the broader histories and mythologies the party drew on to establish the basis for its moral crusade. -

Greenpeace, Earth First! and the Earth Liberation Front: the Rp Ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America" (2008)

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2008 Greenpeace, Earth First! and The aE rth Liberation Front: The rP ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America Christopher J. Covill University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Covill, Christopher J., "Greenpeace, Earth First! and The Earth Liberation Front: The rP ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America" (2008). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 93. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/93http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Greenpeace, Earth First! and The Earth Liberation Front: The Progression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America Christopher John Covill Faculty Sponsor: Professor Timothy Hennessey, Political Science Causes of worldwide environmental destruction created a form of activism, Ecotage with an incredible success rate. Ecotage uses direct action, or monkey wrenching, to prevent environmental destruction. Mainstream conservation efforts were viewed by many environmentalists as having failed from compromise inspiring the birth of radicalized groups. This eventually transformed conservationists into radicals. Green Peace inspired radical environmentalism by civil disobedience, media campaigns and direct action tactics, but remained mainstream. Earth First’s! philosophy is based on a no compromise approach. -

A History of Modern Palestine

A HISTORY OF MODERN PALESTINE Ilan Pappe’s history of modern Palestine has been updated to include the dramatic events of the s and the early twenty-first century. These years, which began with a sense of optimism, as the Oslo peace accord was being negotiated, culminated in the second intifada and the increase of militancy on both sides. Pappe explains the reasons for the failure of Oslo and the two-state solution, and reflects upon life thereafter as the Palestinians and Israelis battle it out under the shadow of the wall of separation. I P is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Haifa in Israel. He has written extensively on the politics of the Middle East, and is well known for his revisionist interpretation of Israel’s history. His books include The Making of the Arab–Israeli Conflict, – (/) and The Modern Middle East (). A HISTORY OF MODERN PALESTINE One Land, Two Peoples ILAN PAPPE University of Haifa, Israel CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521683159 © Ilan Pappe 2004, 2006 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Second edition 2006 7th printing 2013 Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by the MPG Books Group A catalog record for this publication is available from the British Library. -

The Evolution of Radical Rhetoric: Radical Baby Boomer

THE EVOLUTION OF RADICAL RHETORIC: RADICAL BABY BOOMER DISCOURSE ON FACEBOOK IN THE 21ST CENTURY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY EDWIN FAUNCE ADVISOR: JAMES W. CHESEBRO BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2012 2 Table of Contents Title Page 1 Table of Contents 2 Dedication 3 Acknowledgement 4 Chapter 1: The Problem 5 Chapter 2: LiteratUre Review 11 Chapter 3: Method 24 Chapter 4: Boomer Profile Analysis ConclUsions 47 Chapter 5: Final ConclUsions, Limitations, and Recommendations 58 Works Cited 68 Appendix 74 3 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my children, Rachel and Abigail, with my loVe and admiration. 4 ACknowledgements First and foremost I want to thank and acknowledge my adVisor, and committee chair James W. Chesebro Ph.D. for his gUidance, and extreme hard work coaching and helping me figUre oUt what was in my head. Next, I want to also thank my committee members. I want to thank Michael Holmes Ph.D. for his continued thoughtful and incisive input to this thesis from when it was just an idea rUminating in my head Up to the work that you see before you. I want to thank Melinda Messineo Ph.D. for her encoUragement and help to focus on my topic while I was assembling this thesis proposal. Thank yoU all for yoUr stellar work on this thesis committee. I would like to acknowledge Michael Gerhard Ph.D. for his direction and encoUragement, and also thank the rest of my master’s cohort for listening to the many pedantic papers and lectUres they had to endUre on the sUbject of the elderly on Facebook. -

5195E05d4.Pdf

ILGA-Europe in brief ILGA-Europe is the European Region of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans & Intersex Association. ILGA-Europe works for equality and human rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans & intersex (LGBTI) people at European level. ILGA-Europe is an international non-governmental umbrella organisation bringing together 408 organisations from 45 out of 49 European countries. ILGA-Europe was established as a separate region of ILGA and an independent legal entity in 1996. ILGA was established in 1978. ILGA-Europe advocates for human rights and equality for LGBTI people at European level organisations such as the European Union (EU), the Council of Europe (CoE) and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). ILGA-Europe strengthens the European LGBTI movement by providing trainings and support to its member organisations and other LGBTI groups on advocacy, fundraising, organisational development and communications. ILGA-Europe has its office in Brussels and employs 12 people. Since 1997 ILGA-Europe enjoys participative status at the Council of Europe. Since 2001 ILGA-Europe receives its largest funding from the European Commission. Since 2006 ILGA-Europe enjoys consultative status at the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (ECOSOC) and advocates for equality and human rights of LGBTI people also at the UN level. ILGA-Europe Annual Review of the Human Rights Situation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex People in Europe 2013 This Review covers the period of January -

Homage to Edward Thompson, Part I Bryan D

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 05:13 Labour/Le Travailleur Homage to Edward Thompson, Part I Bryan D. Palmer Volume 32, 1993 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/llt32ob01 Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Canadian Committee on Labour History ISSN 0700-3862 (imprimé) 1911-4842 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Palmer, B. D. (1993). Homage to Edward Thompson, Part I. Labour/Le Travailleur, 32, 10–72. All rights reserved © Canadian Committee on Labour History, 1993 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ OBITUARY / NÉCROLOGIE Homage to Edward Thompson, Parti Bryan D. Palmer EDWARD PALMER (E.P.) THOMPSON, described in 1980 as "our finest socialist writer today — certainly in England, possibly in Europe,"1 died at his home, Wick Episcopi, Worcester on 28 August 1993. Born 3 February 1924, he is survived by his wife of 45 years, fellow historian and political comrade, Dorothy, their daughter Kate, sons Mark and Ben, and numerous grandchildren. He left us—whom I define as those interested in and committed to the integrity of the past and the humane possibilities of a socialist future — a most enduring legacy, his example. -

Kennedycollection.Pdf

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: Special Collection Title: Kennedy Collection Scope: A collection of books on Japan and the Far East, including China, mainly in the 20th century. Dates: 1891-1979 Extent: c. 350 vols. Name of creator: Malcolm Duncan Kennedy Administrative / biographical history: Malcolm Duncan Kennedy, O.B.E., (1895-1984), expert on Japanes affairs, had a varied career as army officer, businessman, civil servant and intelligence officer, during which he spent some two decades in Japan. Kennedy was born in Edinburgh, though some of his earliest years were spent in Penang, and educated at Glenalmond School. During his army career he attended Sandhurst before serving in the First World War. After being severely wounded he convalesced for eighteen months before taking a course in Japanese at SOAS, having been posted to the Intelligence Section of Eastern Command Headquarters in London. From 1917 to 1920 he was a Military Language Officer in Japan, before returning to London where he worked in the Far Eastern Section of the War Office. The following year he was invalided out of the army and returned to Japan as a businessman. From 1925 until 1934 he took up a post in the Japanese Section of the Government Dode and Cypher School, combining this with free-lance journalism. During World War II he continued to work there on Far Eastern Intelligence duties. At the end of the war he moved to the War Office, being based in the headquarters of the Inter-Service Organisation. From 1945 until his retirement in 1955 he worked for S.I.S. -

Dataset of Electoral Volatility in the European Parliament Elections Since 1979 Codebook (July 31, 2019)

Dataset of Electoral Volatility in the European Parliament elections since 1979 Vincenzo Emanuele (Luiss), Davide Angelucci (Luiss), Bruno Marino (Unitelma Sapienza), Leonardo Puleo (Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna), Federico Vegetti (University of Milan) Codebook (July 31, 2019) Description This dataset provides data on electoral volatility and its internal components in the elections for the European Parliament (EP) in all European Union (EU) countries since 1979 or the date of their accession to the Union. It also provides data about electoral volatility for both the class bloc and the demarcation bloc. This dataset will be regularly updated so as to include the next rounds of the European Parliament elections. Content Country: country where the EP election is held (in alphabetical order) Election_year: year in which the election is held Election_date: exact date of the election RegV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between parties that enter or exit from the party system. A party is considered as entering the party system where it receives at least 1% of the national share in election at time t+1 (while it received less than 1% in election at time t). Conversely, a party is considered as exiting the part system where it receives less than 1% in election at time t+1 (while it received at least 1% in election at time t). AltV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between existing parties, namely parties receiving at least 1% of the national share in both elections under scrutiny. OthV: electoral volatility caused by vote switching between parties falling below 1% of the national share in both the elections at time t and t+1. -

Communism As a Way of Life, the Communist Party Historians’ Group and Oxford Student Politics

1 The Ingrained Activist: Communism as a Way of Life, the Communist Party Historians’ Group and Oxford Student Politics When Richard Lloyd Jones came to look back on his wartime school days at Long Dene, a progressive boarding school in Buckinghamshire, one particular incident stuck in his mind.1 He remembered being kept awake during the hot summer of 1944. It was not the heat alone that was responsible for this. Nor was there any particular physical reason why he should have been so wakeful. Part of the school’s ethos was a strenuous emphasis on the pupils participating in forms of outdoor and rural work such as harvesting. All that fresh air and exercise should have been quite sufficient to exhaust even the most active of small boys. What kept Richard Lloyd Jones awake was the incessant talking of a young, hyperactive ‘Raf-Sam’. Lloyd Jones did not recall exactly what it was that so animated the juvenile Samuel, late into that sticky summer’s night, but a reasonable assumption would be that it was politics, specifically communist politics, as the nine-year-old Samuel was already practising his skills as an aspiring communist propagandist and organiser.2 1 Lloyd Jones later became Permanent Secretary for Wales (1985–93) and Chairman for the Arts Council of Wales (1994–99). 2 Richard Lloyd Jones quoted in Sue Smithson, Community Adventure: The Story of Long Dene School (London: New European Publications, 1999), 21. See also: Raphael Samuel, ‘Family Communism’, in The Lost World of British Communism (London: Verso, 2006), 60; Raphael Samuel, ‘Country Visiting: A Memoir’, in Island Stories: Unravelling Britain (London: Verso, 1998), 135–36. -

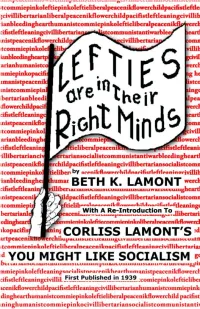

LEFTIES ARE in THEIR RIGHT MINDS Part One

LEFTIES ARE IN THEIR RIGHT MINDS LEFTIES ARE IN THEIR RIGHT MINDS Part One By Beth K. Lamont April 2009 And A Re-Introduction to Corliss Lamont’s You Might Like Socialism First Published in 1939 HALF-MOON FOUNDATION, INC. The Half-Moon Foundation was formed to promote enduring inter- national peace, support for the United Nations, the conservation of our country’s natural environment, and to safeguard and extend civil liberties as guaranteed under the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Lefties Are In Their Right Minds Copyright © 2009 by Beth K. Lamont All rights reserved. Published by Half-Moon Foundation, Inc. ISBN 978-0-578-00782-3 You Might Like Socialism: A Way of Life for Modern Man Copyright © 1939 by Corliss Lamont Originally published by Modern Age Books, Inc. New York, NY Visit the Corliss Lamont Web site http://www.corliss-lamont.org/ Printed in the United States of America Preface Actually, there’s no need for you to read this book at all! The title sums up its whole thesis. When I say Lefties Are In Their Right Minds, I’m trying to give a whimsical approach to a very serious subject. The Righties of this world, who still believe that their might makes them right, have been wrong for too long. That’s why I’m urging: Lefties, it’s you who are right! Check-out a true Leftie-Life-Line: Pacifica Radio, especially its New York Station, @ FM 99.5 WBAI! We're gathering strength! We need to Unite! And what perfect timing. Unbridled Capitalism is in disgrace; I picture rowdy, irresponsible teenagers behaving badly and Big Daddy having to bail them out of jail. -

Milan St. Protić the Serbian Radical Movement

Milan St. Protić The Serbian Radical Movement – A Historical Aspect Following the Serbo-Turkish war (–) an outburst of dynamic po- litical events culminated in the early s with the formation of modern political parties in Serbia. This phenomenon resulted from several impor- tant factors. Although the promulgation of the Constitution in had not yet established full parliamentary democracy, it had secured a political environment in which larger segments of society could take an active part in political decision making. This political document expressed a compro- mise between the Crown and the National Assembly by dividing legislative authority, eliminating the previous oligarchic political tradition and almost unlimited power of the ruler. Secondly, after the assassination of Prince Mihailo Obrenović in , Serbia was ruled by his minor nephew Prince Milan Obrenović who was represented by the Regency. The Regency was dominated by a strong political personality, later founder of the Liberal Party, European-educated Jovan Ristić. The ruling circles felt a need to introduce certain reforms based on Western political experience. Thirdly, as a consequence of the Serbo-Turkish war and the Congress of Berlin in , Serbia became an independent state with all the prerogatives of power and importance that such a position acquires. Fourthly, during this period a number of young Serbian students were sent to European universities to receive higher education. Exposure to European political developments, movements, and ideas accompanied them back to Serbia. Finally, Serbian society politically matured and entered the partisan struggle. Serbian society, dominated by the peasantry, passed through several stages of national consciousness. They began by opposing the Ottoman rule and laying the foundations for a nation-state at the beginning of the nine- teenth century, progressed through opposing the very same State’s estab- Slobodan Jovanović, Vlada Milana Obrenovića, vol.