Australia's First Socialists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Workingman's Paradise": Pioneering Socialist Realism

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online William Lane's "The Workingman's Paradise": Pioneering Socialist Realism Michael Wilding For their part in the 1891 Australian shearers' strike, some 80 to 100 unionists were convicted in Queensland with sentences ranging from three months for 'intimidation' to three years for 'conspiracy'. It was to aid the families of the gaoled unionists that William Lane wrote The Workingman's Paradise (1892). 'The first part is laid during the summer of 1888-9 and covers two days; the second at the commencement of the Queensland bush excitement in 1891, covering a somewhat shorter time.' (iii) The materials of the shearers' strike and the maritime strike that preceded it in 1890 are not, then, the explicit materials of Lane's novel. But these political confrontations are the off-stage reference of the novel's main characters. They are a major unwritten, but present, component of the novel. The second chapter of part II alludes both to the defeat of the maritime strike and the beginnings ofthe shearers' strike, forthcoming in the novel's time, already defeated in the reader's time. Those voices preaching moderation in the maritime strike, are introduced into the discussion only to be discounted. The unionists who went round 'talking law and order to the chaps on strike and rounding on every man who even boo'd as though he were a blackleg' have realised the way they were co-opted and used by the 'authorities'. 'The man who told me vowed it would be a long time before he'd do policeman's work again. -

Recorder 298.Pages

RECORDER RecorderOfficial newsletter of the Melbourne Labour History Society (ISSN 0155-8722) Issue No. 298—July 2020 • From Sicily to St Lucia (Review), Ken Mansell, pp. 9-10 IN THIS EDITION: • Oil under Troubled Water (Review), by Michael Leach, pp. 10-11 • Extreme and Dangerous (Review), by Phillip Deery, p. 1 • The Yalta Conference (Review), by Laurence W Maher, pp. 11-12 • The Fatal Lure of Politics (Review), Verity Burgmann, p. 2 • The Boys Who Said NO!, p. 12 • Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin (Review), by Nick Dyrenfurth, pp. 3-4 • NIBS Online, p. 12 • Dorothy Day in Australia, p. 4 • Union Education History Project, by Max Ogden, p. 12 • Tribute to Jack Mundey, by Verity Burgmann, pp. 5-6 • Graham Berry, Democratic Adventurer, p. 12 • Vale Jack Mundey, by Brian Smiddy, p. 7 • Tribune Photographs Online, p. 12 • Batman By-Election, 1962, by Carolyn Allan Smart & Lyle Allan, pp. 7-8 • Melbourne Branch Contacts, p. 12 • Without Bosses (Review), by Brendan McGloin, p. 8 Extreme and Dangerous: The Curious Case of Dr Ian Macdonald Phillip Deery His case parallels that of another medical doctor, Paul Reuben James, who was dismissed by the Department of Although there are numerous memoirs of British and Repatriation in 1950 for opposing the Communist Party American communists written by their children, Dissolution Bill. James was attached to the Reserve Australian communists have attracted far fewer Officers of Command and, to the consternation of ASIO, accounts. We have Ric Throssell’s Wild Weeds and would most certainly have been mobilised for active Wildflowers: The Life and Letters of Katherine Susannah military service were World War III to eventuate, as Pritchard, Roger Milliss’ Serpent’s Tooth, Mark Aarons’ many believed. -

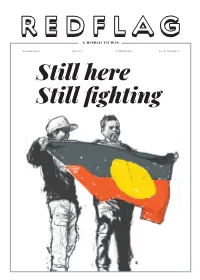

RF177.Pdf (Redflag.Org.Au)

A WORLD TO WIN REDFLAG.ORG.AU ISSUE #177 19 JANUARY 2021 $3 / $5 (SOLIDARITY) Still here Still fi ghting REDFLAG | 19 JANUARY 2021 PUBLICATION OF SOCIALIST ALTERNATIVE REDFLAG.ORG.AU 2 Red Flag Issue # 177 19 January 2021 ISSN: 2202-2228 Published by Red Flag Support the Press Inc. Trades Hall 54 Victoria St Carlton South Vic 3053 [email protected] Christmas Island (03) 9650 3541 Editorial committee Ben Hillier Louise O’Shea Daniel Taylor Corey Oakley rioters James Plested Simone White fail nonetheless. Some are forced to complete rehabil- Visual editor itation programs and told that when they do so their James Plested appeals will be strengthened. They do it. They fail. These are men with families in Australia. They Production are workers who were raising children. They are men Tess Lee Ack n the first week of 2021, detainees at the Christ- who were sending money to impoverished family Allen Myers mas Island Immigration Detention Centre be- members in other countries. Now, with their visas can- Oscar Sterner gan setting it alight. A peaceful protest, which celled, they have no incomes at all. This has rendered Subscriptions started on the afternoon of 5 January, had by partners and children homeless. and publicity evening escalated into a riot over the treatment Before their transportation from immigration fa- Jess Lenehan Iof hundreds of men there by Home Affairs Minister cilities and prisons on the Australian mainland, some Peter Dutton and his Australian Border Force. Four of these men could receive visits from loved ones. Now What is days later, facing down reinforced numbers of masked, they can barely, if at all, get internet access to speak to armed Serco security thugs and Australian Federal them. -

Romantic Nationalism and the Descent Into Myth

Romantic Nationalism and the Descent into Myth: William Lane's Th e Wo rkingman 's Paradise ANDREW McCANN University of Melbourne he study of Australian lit�rature has been and no doubt still is a fo rm of nationalist pedagogy in which the primary object of nationalist discourse, the people, is emblematisedT in the fo rmation of a literary culture. The easy simultaneity of text and populace implied here is a recurring trope in the writing of Australian cultural history. Needless to say the 1890s is the decade that most clearly embodies this simul taneity in its foregrounding of an apparent movement from Romanticism to a more directly political realism. The narrative of the people's becoming, in other words, involves a stylistic shift that is seen as integral to, even constitutive of, political consciousness in the years before Federation. By this reckoning, the shift to realism concretises the perception of locality, the sense of time and space, we associate \•lith the nation. Realism effects, in Mikhail Bakhtin's words, 'a creative humanisation of this locality, which transforms a part of terrestrial space into a place of historical life for people' (31). The trouble with this version of Australian literary history is that it mistakes obvious stylistic differences for a genuine and radical discursive shift. In positing the movement from Romanticism to realism as the key to national becoming it assumes a direct correspondence between the aesthetic and the ideological. This elides what, looking from a slightly different angle, is equally obvious about late-nineteenth Ct'ntury Australian nationalism, and perhaps nationalism in general: that is, the nation, with its attendant notions of organically bonded community, locality and autochthony, is not simply haunted by Romanticism, it is unambiguously Romantic. -

Socialism and the ALP Left

John Sendy Socialism and the ALP Left THE FEDERAL TAKE-OVER of the Victorian Labor Party, inspired by rightwing policies, ruling class desires and the ambi tions of attaining electoral victory at any cost, has proved a grand failure, irrespective of what occurs in the next weeks. The interventionists had a completely unreal estimate of the situation in Victoria and have proved quite unequal to the job undertaken. They in no way realised the depth of support for Hartley, Hogg and their colleagues. Estimating that Hartley, Hogg & Co. would have only a handful of supporters faced with strong-arm tactics, they to a large degree were paralysed by the strength and full-blooded nature of the opposition and defiance which they confronted from a membership sickened by the traditional parliamentary antics of a Whitlam and the hare brained, opportunist, power-game manoeuvrings of a Cameron. The idea of reforming the ALP to enhance its 1972 electoral prospects by eliminating “the madmen of Victoria” in exchange for some curbing of the rightwing dominance in NSW was swal lowed readily by sundry opportunistic, unprincipled “left wingers" in NSW and Victoria obsessed with positions and “power” and with achieving the “advance” of electing a Labor Government under Whitlam. The “Mad Hatters tea party” of Broken Hill was fol lowed by the circus-style orgy of the Travel Lodge Motel in the John Sendy is Victorian Secretary of the Communist Party. This article was written in mid-January. 2 AUSTRALIAN LEFT REVIEW— MARCH, 1971 full glare of television cameras and the shoddy backroom dealings of the dimly lit Chinese cafes of Sydney. -

The Making of White Australia

The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888 Philip Gavin Griffiths A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University December 2006 I declare that the material contained in this thesis is entirely my own work, except where due and accurate acknowledgement of another source has been made. Philip Gavin Griffiths Page v Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xiii Abstract xv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 A review of the literature 4 A ruling class policy? 27 Methodology 35 Summary of thesis argument 41 Organisation of the thesis 47 A note on words and comparisons 50 Chapter 2 Class analysis and colonial Australia 53 Marxism and class analysis 54 An Australian ruling class? 61 Challenges to Marxism 76 A Marxist theory of racism 87 Chapter 3 Chinese people as a strategic threat 97 Gold as a lever for colonisation 105 The Queensland anti-Chinese laws of 1876-77 110 The ‘dangers’ of a relatively unsettled colonial settler state 126 The Queensland ruling class galvanised behind restrictive legislation 131 Conclusion 135 Page vi Chapter 4 The spectre of slavery, or, who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 137 The political economy of anti-slavery 142 Indentured labour: The new slavery? 149 The controversy over Pacific Islander ‘slavery’ 152 A racially-divided working class: The real spectre of slavery 166 Chinese people as carriers of slavery 171 The ruling class dilemma: Who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 176 A divided continent? Parkes proposes to unite the south 183 Conclusion -

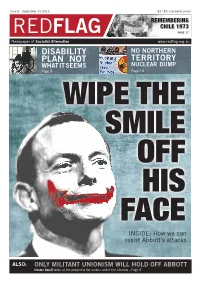

Red Flag Issue8 0.Pdf

Issue 8 - September 10 2013 $3 / $5 (solidarity price) REMEMBERING FLAG CHILE 1973 RED PAGE 17 Newspaper of Socialist Alternative www.redfl ag.org.au DISABILITY NO NORTHERN PLAN NOT TERRITORY WHAT IT SEEMS NUCLEAR DUMP Page 8 Page 13 WIPE THE SMILE OFF HIS FACE INSIDE: How we can resist Abbott’s attacks ALSO: ONLY MILITANT UNIONISM WILL HOLD OFF ABBOTT Jerome Small looks at the prospects for unions under the Liberals - Page 9 2 10 SEPTEMBER 2013 Newspaper of Socialist Alternative FLAG www.redfl ag.org.au RED CONTENTS EDITORIAL 3 How Labor let the bastards in Mick Armstrong analyses the election result. 4 Wipe the smile off Abbott’s face ALP wouldn’t stop Abbo , Diane Fieldes on what we need to do to fi ght back. now it’s up to the rest of us 5 The limits of the Greens’ leftism A lot of people woke up on Sunday leader (any leader) and wait for the 6 Where does real change come from? a er the election with a sore head. next election. Don’t reassess any And not just from drowning their policies, don’t look seriously about the Colleen Bolger makes the argument for getting organised. sorrows too determinedly the night deep crisis of Laborism that, having David confront a Goliath in yellow overalls before. The thought of Tony Abbo as developed for the last 30 years, is now prime minister is enough to make the at its most acute point. Jeremy Gibson reports on a community battling to keep McDonald’s soberest person’s head hurt. -

Literature and the Late-Victorian Radical Press

Literature Compass 7/8 (2010): 702–712, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00729.x Literature and the Late-Victorian Radical Press Elizabeth Carolyn Miller* University of California, Davis Abstract Amidst a larger surge in the number of books and periodicals published in late-nineteenth-century Britain, a corresponding surge occurred in the radical press. The counter-cultural press that emerged at the fin de sie`cle sought to define itself in opposition to commercial print and the capitalist press and was deeply antagonistic to existing political, economic, and print publishing structures. Litera- ture flourished across this counter-public print sphere, and major authors of the day such as William Morris and George Bernard Shaw published fiction, poetry, and literary criticism within it. Until recently, this corner of late-Victorian print culture has been of interest principally to historians, but literary critics have begun to take more interest in the late-Victorian radical press and in the literary cultures of socialist newspapers and journals such as the Clarion and the New Age. Amidst a larger surge in the number of books and periodicals published in Britain at the end of the nineteenth century, a corresponding surge occurred in the radical press: as Deian Hopkin calculates, several hundred periodicals representing a wide array of socialist perspectives were born, many to die soon after, in the decades surrounding the turn of the century (226). An independent infrastructure of radical presses, associated with various radical organizations and editors, emerged as an alternative means of periodical production apart from commercial, profit-oriented print.1 Literature and literary discourse flourished across this counterpublic sphere, and major authors of the day published fiction, poetry, and journalism within it: in the 1880s, for example, William Morris spent five years editing and writing for the revolutionary paper Commonweal, while George Bernard Shaw cut his teeth as an author by serializing four novels in the socialist journals To-Day and Our Corner. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Children of the Red Flag Growing Up in a Communist Family During the Cold War: A Comparative Analysis of the British and Dutch Communist Movement Elke Marloes Weesjes Dphil University of Sussex September 2010 1 Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 2 Abstract This thesis assesses the extent of social isolation experienced by Dutch and British ‘children of the red flag’, i.e. people who grew up in communist families during the Cold War. This study is a comparative research and focuses on the political and non-political aspects of the communist movement. By collating the existing body of biographical research and prosopographical literature with oral testimonies this thesis sets out to build a balanced picture of the British and Dutch communist movement. -

Recorder Vol. 1 No. 2 September 1964

oa ros Recorder <> MELBOURNE BRANCH AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF LABOUR HISTORY Vol 1. No. 2. September 19SL EDITORIAL productionDrnfinot-inS ,?,was not+ commencedall we would with wish the for. previous This issueissue andwill the come standard through of production^'^'^^ Letter. Cost is a factor in the andQnr^ anyon^r ??++little will helpfpom to Othergenerate members collective v;ill he activity,v/elcomed immediatelyin return vou may secure a "missing linlc" long sought. x y, la reiiurn you Street,Q+v,^ + Moonee Ponds. should he sent to S. xMerrifield, 81 VVaverley THE ItNfTERNATIONALS 28/q/lfifih^«t^Q? founding of the First International on in humanhnmon >.?history + which ^have ^ ^resulted J^ondon. from It this.is hard' to SiSSess the changes 10711871 were other signs of future17S2, events. 1830, 181+8 and the later Commune of tnto ■Pnr.mform an associationsarly _ as 1839, in London,German worlcnen expelled from Paris attempted giveffivc. ao lead to anotherMarx and efx.ort Engels in produced international the "Communist co-operation. Manifesto" to ff nvp ininternational London at the meetings, time of thetwo 1862 on 28A/1863Exhibition and Government\ in supportSt.James of the Hall Polish demanded insurrection the intervention agains? CzLis? hy the pSIsifEnglish Classes , rmed in I800 oy the karquessMaterial Townshend, Elevation gave aof furtherthe Industrial lead, P^^liifii^inry meetings in June and July were followed hv thP l5/7/18ys"°*^®'' ''•®- dtlesatos only was held at Philadelphia on in Ootobe5°1881°Sto X ao Ohor?nd^??nal?rw''"r?^'"Jonur anu iinally was held in Paris on lh/7/1889. -

The Red North

The Red North Queensland’s History of Struggle Jim McIlroy 2 The Red North: Queensland’s History of Struggle Contents Introduction................................................................................................3 The Great Shearers’ Strikes of the 1890s ....................................5 Maritime Strike................................................................................................. 6 1891 battleground............................................................................................. 8 1894: the third round...................................................................................... 11 Lessons of the 1890s strikes........................................................................... 11 The Red Flag Riots, Brisbane 1919 ..............................................13 Background to the 1919 events...................................................................... 13 ‘Loyalist’ pogrom............................................................................................ 16 The Red North.........................................................................................19 Weil’s Disease................................................................................................. 20 Italian migrants............................................................................................... 21 Women........................................................................................................... 22 Party press..................................................................................................... -

UQFL241 Ted and Eva Bacon Papers

FRYER LIBRARY Manuscript Finding Aid UQFL241 Ted and Eva Bacon Papers Size 17 boxes, 3 albums, 1 parcel Contents Correspondence, minutes, typescript articles, reports, circular letters, photographs. Date range 1936 - 1993. Bulk of collection from 1970s and 1980s. Biography Edwin Alexander (Ted) and Eva Bacon were both members of the Communist Party of Australia. Eva Bacon was also a member of the Union of Australian Women. She was especially active in women's and peace issues. Ted Bacon was on various CPA bodies and worked for Aboriginal rights. Notes Mostly open access; some restrictions. Related material can be found in UQFL234 Communist Party of Australia (Queensland Branch) Collection. Box 1 Peace [Comparison between 1966 Conference on S.E. Asia and Australia, and 1963 Conference on Peace and the People’s Needs]. 6 leaves handwritten [by Ted Bacon?] What way out in Vietnam? 2 versions, varying numbers of handwritten and typed leaves, handwriting of Ted Bacon (?) Letter to Ted [Bacon] from Joyce. Undated. 2 leaves typescript. Party work. Leaflets Handwritten note: Assorted leaflets. 1 leaf. Plastic bag with handwritten sticker: Assorted leaflets. ‘The arms race - humanity at risk’. 4 pages printed. Application form to attend the Australian People’s Disarmament Conference, 1978. Bombed in Vietnam. 4 pages printed. Communist Party of Australia. China must get out of Vietnam, stop the war from spreading. 1 leaf duplicated typescript, dated 1979 in ballpoint. Issued by the Hands Of[f] Vietnam Committee. Rally. The Communist Party is behind this Moratorium - way behind. 4 pages printed. Authorised by B. Laver. Dissension. Conscription and you! 2 pages duplicated typescript.