Marketing of Environmentally Sustainable Ski Center Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Info Hiver 2020-2021

INFO HIVER 2020-2021 WINTER 2020-2021 Q Parquage libre I Free parking Q Zone limitée 2 heures I Limited to 2 hours Q Autorisé de 08:00 à 20:00 I You can park from 8am to 8pm Parking ski au pied I Ski in / ski out Q Autorisé de 07:00 à 23:00 I You can park from 7am to 11pm Q Dépose minute I Drop off point LÉGENDES I LEGENDS Office du tourisme I Tourist office (D3) Salle communale I Community center (D3) Kids club (D3) Piscine couverte, Sauna Indoor swimming pool, Sauna (D2) La Poste I Post office (D3) Supermarché I Supermarket Boucherie I Butcher (D3) Blanchisserie I Laundry (C3) Patinoire I Ice rink (D3) Raquette à neige I Snowshoeing (C2) Sentier hivernal I Winter trail (C2) Borne de recharge I Charging station (D3) Restaurants I Restaurants A) La Tzoumaz (E3) E) Les Fougères (C3) B) La Maison de la Forêt (B2) F) Les Trappeurs (C3) C) La Poste & Pub (D3) G) T-Bar (D3) D) Les Etablons (C2) Location de matériel I Ski rental 1 - Monnet Sports (D3) 3 - T-shop (D3) 2 - Perraudin Sports (D3) Écoles de ski I Ski school 4 - École Suisse de Ski et Snowboard (D2) 5 - Tzoum’Evasion (D3) Agences immobilières I Rental agencies 6 - Carron Immobilier (D3) 9 - SwissKeyChalet (D4) 7 - 4 Vallées 4 Saisons (C3) 10 - Home Partner (C3) 8 - Résidence-Swiss (C3) Récolte des déchets I Waste collect (E3) Papiers I Paper Verres/PET I Glass/PET Moloks I Waste Aluminium Déchets alimentaires I Waste foot Hébergement I Accomodation A) Auberge de la Tzoumaz (E3) H) La Tzoum’Hostel C) Hôtel de la Poste (D3) & Chalet (D4) E) Chalet les Fougères SA (D3) I) Résidence La Tzoumaz Verbier (D3) BIENVENUE WELCOME WILLKOMMEN Au vu de l’évolution de la situation sanitaire actuelle, nous vous recommandons de vérifier l’exactitude des informations fournies dans cette brochure sur notre site internet www.latzoumaz.ch ou auprès de l’office du Tourisme au +41 (0)27 305 16 00. -

Swiss Alps - Veyson

Swiss Alps - Veyson Ref. V02 Chalet Endymion ???????: 6 ???????: 5 Endymion is beautifully decorated luxury Alpine chalet situated in the traditional Swiss village of Veysonnaz, in the heart of The 4 Valleys, Switzerland's most extensive ski resort. Main living areas with extensive seating, entertainment areas, reading areas, open log fire, floor to ceiling windows and balcony access with spectacular views across the valleys. Endymion is located on the slopes just above Veysonnaz - part of the massive Les 4 Vallées ski area (more than 400 kilometres of pistes/100 lifts) - about an hours skiing from Verbier, Nendaz, & La Tzoumaz. It is Drive in/Drive out and Ski in/Ski out, situated adjacent to the piste between Thyon and Veysonnaz. Skiing down to the Magrappe Gondola takes 2 minutes. Located at 1,500 metres, this secluded luxury ski chalet offers breathtaking views across the Rhône Valley. Veysonnaz is a charming old village made up of traditional chalets and low rises, and has an optimal climate boasting 300 days sunshine on average per year, meaning increased chances of quality winter as well as summer activities. Switzerland’s oldest town, Sion, is only 20 minutes away with its two medieval castles, numerous churches and museums. Verbier (60 minutes) and Crans-Montana (50 minutes) offer extensive skiing as well as luxury shopping, dining and top end golf courses. Picturesque, lake-side Montreux (50 minutes) is famous for its annual international Jazz Festival. Chalet living and sleeping Sleeps 12-14 people 5-6 bedrooms, 5 bathrooms Each room has under-floor heating with individual thermostats All beds have luxurious mattress toppers and Egyptian cotton linen The two master suites have en-suite bathrooms Living Room Double height windows with spectacular views of the valley 3 separate seating areas Log fire 200 channel satellite TV Sony music system Dining / Kitchen 12 seater dining table with spectacular valley views opening onto the terrace and outdoor entertainment area. -

Verbier, Switzerland Jan 30 Thru Feb 7, 2015

Verbier, Switzerland Jan 30 thru Feb 7, 2015 $2,550 Per Person / Double Occupancy Optional extension to be determined if group desires Feb 8–10 What’s Included • Round trip non-stop air transportation from Boston to Zurich on Swiss Air • Motor coach transfers to and from Airports & hotels • 7 nights lodging at the Hotel de Verbier • Full Breakfast and afternoon tea & cake – • 5-course evening meal with choice of menu, including pre dinner aperitif, choice of wines with dinner followed by tea/coffee & chocolates(6 nights) • One night fondue dinner at La Caveau (*or similar venue) • Welcome party on arrival • All hotel taxes and fees included & gratuities What’s not included • Lunch, Discounted Lift tickets and side trips Accommodations The Hotel de Verbier provides a superb base from which to explore Verbier and the spectacular “4 Valleys” ski area. The hotels public areas are furnished in an attractively rustic Swiss style and provide a warm and welcoming atmosphere, with a comfortable and spacious lounge with a log fireplace, where afternoon tea and cakes are served daily, and an adjoining bar with TV. All the bedrooms were refurbished to a high standard in a modern style for winter of 2014 and have private bath or shower/wc, along with many having a balcony. All communal areas off free WI/FI and there is a lift for convenience to upper floors. Location The Medran gondolas are less than a 5 minute walk or take the free ski bus which stops just 50m from the hotel. Located in the center of town you will be right in the middle of the nightlife area. -

Nous Soutenons Le Grand Raid

1 4 7 Nous soutenons le Grand Raid verbier veysonnaz evolène Verbier > En été, Verbier et le Val de Bagnes offrent un cadre magni- During summertime Verbier Val de Bagnes offers a magnificent setting Veysonnaz > Là où la montagne élargit votre horizon…Cette The lookout post of the Alps, Veysonnaz is the crossroad to Evolène > Un village de montagne typique avec son but festif, A typical mountain village with its festive purpose, culture, tra- fique pour découvrir les multiples facettes de la montagne. Alliant le to discover the many facets of the mountain. Combining sport, cul- petite station pour les sportifs et familles est un véritable balcon several valleys and has an exceptional panoramic view. culture, tradition et gastronomie. Une région où l’authenticité dition and gastronomy. Authenticity and traditional life are still sport, la culture et la gastronomie, Verbier et le Val de Bagnes enchan- ture and gastronomy, Verbier Val de Bagnes enchants curious visitors de la vie traditionnelle est toujours présente. present. tent les visiteurs curieux au travers d’une multitude d’événements et through a plethora of events and activities. From the concerts of the sur les Alpes au panorama exceptionnel ! Située au cœur des 4 d’activités. Des concerts du Verbier Festival à la Patrouille des Glaciers, Verbier Festival to the Patrouille des Glaciers race, to the bike paths Vallées, elle offre des conditions climatiques de rêve en toutes des pistes du Bikepark à Bagnes - Capitale de la raclette, la région of the Bagnes Bikepark to Bagnes- Capital of raclette, the regions vi- saisons. vibre au rythme des saisons « Grandeur Nature ». -

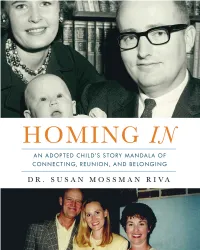

Librarian Review Copy

Copy Review Librarian HOMING IN AN ADOPTED CHILD’S STORY MANDALA OF CONNECTING, REUNION, AND BELONGING DR. SUSAN MOSSMANCopy RIVA Review Virginia Librarian Homing In: An Adopted Child’s Story Mandala of Connecting, Reunion, and Belonging © 2020 by Susan Kay Mossman Riva. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or digital (including photocopying and recording) except for the inclusion in a review, without written permission from the publisher. Because of the dynamic nature of the Internet, any web addresses or links contained in this book may have changed since publication and may no longer be valid. The views expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: all effort has been done to ensure accuracy and ownership of all included information. While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created by sales representatives or written promotional materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. The publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services, and you should consult a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages incurred as a result of using the techniques contained in thisCopy book or any other source reference. -

Les Terrasses De Nendaz NEN DAZ NEN DAZ

Les Terrasses de Nendaz NEN DAZ NEN DAZ 01 LOCATION HAUTE-NENDAZ Haute-Nendaz lies in the heart of the 4 Vallées ski region wich connects Verbier, La Tzoumaz, Nendaz and Thyon/Les Collons. It is the largest ski area of Switzerland. Haute-Nendaz is a family paradies and it has the label Family Destination. The municipality of Nendaz has more than 6,700 inhabitants and is lively all year round. The tourist office and other organizations organize many activities and events for the young and old. In Haute-Nendaz you will find here anything you desire such as: Many restaurants & bars, the main supermarkets (Migros and Coop), various banks, a post office, a wellness ares of 2’200 2m , an outside swimming pool, an ice rink, tennis and squash courts, a gym, playgrounds, a library, a child care center, doctors, a dentist, a vet etc… Restaurant Mont-Rouge Local products 01 LOCATION HAUTE-NENDAZ Haute-Nendaz is located: • 14km from Sion • 168km from Geneva • 284km from Zurich • 261km from Milan • 318km from Lyon • 590km from Munich Ski Mountain bike 02 ACTIVITIES 2’200m2 Wellness area 250km of walking paths 412km of ski slopes 200km of mountain bike tracks 300 days of sunshine per year Family Destination Wellness Family Les Terrasses de Nendaz 02 ACTIVITIES MAP OF THE SKI SLOPES View from the Terrasses de Nendaz 03 LES TERRASSES DE NENDAZ SKI-IN & OUT The building Les Terrasses de Nendaz is under construction on the main ski slope of Haute-Nendaz, in the heart of the 4 Vallées ski area that is the largest ski region of Switzerland. -

Swiss Alps Destination Guide

Swiss Alps Destination Guide Overview of Swiss Alps The Alps contain some of Switzerland's most dramatic landscapes, in a country already well endowed with spectacular scenery and fabulous alpine vistas. Situated at the heart of the Alps, Switzerland shares the mountain range with France, Italy and Austria, and provides winter and summer time enjoyment for skiers, snowboarders, walkers and climbers. Switzerland has the distinction of being home to the first ever ski resort, and since then, over 200 first-class resorts have attracted thousands of Swiss and international downhill and cross-country skiers and snowboarders. The tradition of skiing goes back two centuries. Today, with more than 1,700 mountain railways and ski lifts, renowned ski schools and instructors, the best ski equipment in the world, and outstanding slopes and facilities catering for all levels of ability, it fully deserves its moniker of 'Europe's winter playground'. Key Facts Language: The four official languages are Swiss German, French, Italian and Romansch. Most people know at least three languages, including English. Passport/Visa: The borderless region known as the Schengen area includes the following countries: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, The Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and as of December 2008, Switzerland. All these countries issue a standard Schengen visa that has a multiple entry option that allows the holder to travel freely within the borders of all. It is highly recommended that travellers' passports have at least six months' validity remaining after the intended date of departure from their travel destination. -

Info Été 2020

INFO ÉTÉ 2020 SUMMER I SOMMER 2020 LÉGENDES I LEGEND Office du tourisme I Tourist office Supermarché I Supermarket - Boucherie I Butcher Salle communale I Community centre Piscine couverte, sauna, bronzage en terrasse Indoor swimming pool, sauna, tanning terrace Bancomat I ATM La Poste I Post office Chapelles a) Chapelle de l’Ascension I Ascension chapel b) Chapelle d’été I Summer chapel Fromagerie I Cheese factory Pique-nique I Pic nic place Blanchisserie I Laundry Tennis Football Basketball Volleyball Q Parquage libre I Free parking Q Zone limitée 2 heures Limited to 2 hours Restaurants I Restaurants a) La Tzoumaz b) La Poste b) Le Pub c) Les Trappeurs d) T-Bar e) Le Blanc restaurant f) Les Fougères Location de VTT I Mountain bike rental 1) Perraudin Sports Agences immobilières I Rental agencies 2) Carron Immobilier 3) 4 Vallées 4 Saisons 4) Résidence-Swiss 5) SwissKeyChalet 6) Home Partner Récolte des déchets I Waste collect Papiers I Paper Verres/PET I Glas/PET Moloks I Waste Aluminium Hébergement I Accomodation a) Auberge de la Tzoumaz b) Hôtel de la Poste g) La Tzoum’Hostel h) Résidence La Tzoumaz Points d’intérêt I Points of interest Maison de la forêt I House of the forest Sentier des sens I Trail of the senses Bisse de Saxon, place de pique-nique du Marteau Saxon irrigation channel, The Hammer pic nic place Défis de la rivière I Challenges of the River BIENVENUE WELCOME WILLKOMMEN Cet été nous devons nous adapter aux mesures de sécurité liées au COVID-19. La situation évolue de jour en jour, nos anima- tions et manifestations aussi ! Restez informés en consultant régulière- ment notre site internet ou page Facebook, ou auprès de l’Office du tourisme. -

Real Estate Agencies and Hotels' List

Real estate agencies and hotels’ list Téléverbier SA Case postale 419 CH-1936 Verbier Tél. : +41 27 775 25 11 Fax. : +41 27 775 25 98 Email: [email protected] Web : http://www.verbier4vallees.ch Winter 2017-2018 Hotels 4 Valle es Relais & Châteaux le Chalet d'Adrien***** Chemin des Creux CH-1936 Verbier Tél. : +41 27 771 62 00 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.chalet-adrien.com/index.php/fr/ The Lodge Verbier***** Chemin de Plénadzeu 3 CH-1936 Verbier Tél. : + 44 (0) 208 600 0430 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.virginlimitededition.com/en/the-lodge 2 Chalet de Flore **** Rue de Médran 20 CH-1936 Verbier Tél. : +41 27 775 33 44 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.chalet-flore.ch/ Hôtel Nevaï **** Route de Verbier Station 55 CH-1936 Verbier Tél.: +41 27 775 40 00 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.hotelnevai.com/ 3 Hôtel Montpellier*** Rue du Centre sportif 37 CH-1936 Verbier Tél. : +41 27 775 50 40 Email: [email protected] Web: http://montpelierverbier.ch/fr/ Hôtel Mirabeau *** Route de Ransou 72 CH-1936 Verbier Tél. : +41 27 771 63 35 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.mirabeauhotel.ch 4 Hôtel La Rotonde *** Chemin de la Barmète 2 CH-1936 Verbier Tél. : +41 27 771 65 25 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.hotelrotonde.com/ Hôtel de la Poste *** Rue de Médran 12 CP 334 CH-1936 Verbier Tél: +41 27 771 66 81 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.hotelposteverbier.ch/ 5 Hôtel Phénix *** Rue de la Poste 4 CH-1936 Verbier Tél. -

A Mountain of Emotions Accommodation and Leisure Activities 2015-2016

A mountain of emotions Accommodation and leisure activities 2015-2016 CONTENTS Winter 6-7 4 Vallées, one of the biggest ski areas in the world 8-9 Winter excursions 10-11 Source of adrenaline 12-13 Children’s paradise 14-15 Winter map 16 Winter tariffs 16 Rental of equipment 17 Ski schools 17 Winter walks 18 Top events and weekly activities Summer 20-21 Nendaz in the land of the bisses 22-23 Magic of the summits 24-25 Thirst for adventures 26-27 Passion for folklore 28-29 Summer map 30 Summer tariffs 30 Rental of mountainbikes 31 Top events and weekly activities 32 Label Families Welcome Experiences and accomodation 34-35 Zen attitude 36-37 Pleasure of discovery 38-39 Welcome home 41-42 Hotels & Inns 43 B&B 44 Group accommodation 45 Chalets with hotel services 46 Mountain cabins 47-51 Rental agencies 52 Estate agents 53 Nendaz on the web 53 Brochures and maps 54-56 Accommodation map 57 List of apartment blocks Photos by : M. Blache, E. Bornet, Chalet des Alpes, A. Delhez, A. Fournier, Interhome, J.-P. Guillermin, Sarah Bourne Photography, A. Meniconzi, C. Perret, S. Staub, www.arolle.com, L. Scarascia Impressum Edited by Nendaz Tourisme, Nendaz Printed : 13 000 copies Published and printed : IGN, Nendaz Electronic version of the brochure on www.nendaz.ch FACTS & FIGURES KEY FIGURES Population 6 100 full-time inhabitants Sunshine 300 days per year Area 85,9 km2 Villages 17 Geographic area Swiss Alps Highest point 3336 m (La Rosablanche) Lowest point 492 m (Aproz) Official language French Helsinki 2521 km 04:45 Copenhagen 1370 km 02:00 Oslo -

Ski Heaven, Veysonnaz Ski Heaven Chalet Ski Heaven Is a High Quality Chalet of 14 Apartments Which Shares a Deluxe Spa with Sauna and a Jacuzzi

Ski Heaven, Veysonnaz Ski Heaven Chalet Ski Heaven is a high quality chalet of 14 apartments which shares a deluxe spa with sauna and a Jacuzzi. Completed and ready to occupy, Chalet Ski Heaven is a traditional style chalet of luxury apartments on a sunny West facing plot on the main street of Veysonnaz within easy walking distance of the ski lift. Essential Facts • Finished and available immediately • 250m from the ski lift • In main street near shops and restaurants • Access to the entire Verbier ski area • Sunny position with stunning panoramic views • Spa with sauna and Jacuzzi • Available for foreigners • Last chance to buy a new apartment in Veysonnaz Property Location Chalet Ski Heaven is a high quality chalet of 14 This is a traditional village at 1350m complete with apartments with a shared deluxe spa with sauna and church, charming restaurants and old chalets and a Jacuzzi. Construction started in autumn 2011, and is with beautiful views over the Rhone valley. Above the now finished. old village at 1400m is the ski resort of Veysonnaz with a new high speed lift which takes you directly The apartments are on a sunny West facing plot on into the huge Verbier ski area, which has over 400km the main street of Veysonnaz near the restaurants, of prepared pistes and is the largest and one of the shops and bars and within easy walking distance of most challenging ski areas in Switzerland. the ski lift at the foot of the slopes. The Ski Heaven has huge terraces with glass balconies to catch the afternoon sun and to appreciate the stunning view. -

Download a Brochure

WELCOME TO THE LODGE! From the moment I saw it, I knew WELCOME this beautiful chalet in the Swiss Alps was destined to become my favourite mountain hideaway. I chose SIR RICHARD BRANSON’S Verbier because it’s an amazing year MOUNTAIN RETREAT IN VERBIER, round destination and offers world- PERCHED HIGH IN THE SWISS class skiing, fabulous après-ski and ALPS, IS THE PERFECT YEAR- everything you could wish for in a ROUND ESCAPE. COMPLETE WITH summer escape! Paragliding, rock NINE STUNNING BEDROOMS climbing, mountain biking… you name AND SUITES, AN INDOOR it! I hope you too will enjoy your experience at The Lodge as much POOL, INDOOR AND OUTDOOR as I always do. HOT TUBS AND A FRIENDLY TEAM OF EXPERIENCED STAFF INCLUDING A SPA THERAPIST AND MICHELIN-STAR TRAINED SIR RICHARD BRANSON CHEFS, THE LODGE IS A TRUE ALPINE PARADISE, IDEAL FOR A LUXURY SKI HOLIDAY OR AN ACTIVE SUMMER BREAK. ROOMS MASTER SUITES Your room Located on the top floor (4th floor), with magnificent views The Lodge is the perfect place for holidaying with of the mountains and valley opposite, both Master Suites friends and family. This picture-perfect chalet sleeps are very spacious with feature centrepiece fireplaces, up to 18 adults in seven beautifully decorated luxury a sitting area and mini-bar. For families who would like bedrooms and two stunning Master Suites, all enjoying interconnecting rooms, there’s a secret door in the bookcase views to the valley below. An additional six children can which connect the two Master Suites together. be accommodated in the kid’s bunk room.