05-Ethnobiology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maya Knowledge and "Science Wars"

Journal of Ethnobiology 20(2); 129-158 Winter 2000 MAYA KNOWLEDGE AND "SCIENCE WARS" E. N. ANDERSON Department ofAnthropology University ofCalifornia, Riverside Riverside, CA 92521~0418 ABSTRACT.-Knowledge is socially constructed, yet humans succeed in knowing a great deal about their environments. Recent debates over the nature of "science" involve extreme positions, from claims that allscience is arbitrary to claims that science is somehow a privileged body of truth. Something may be learned by considering the biological knowledge of a very different culture with a long record of high civilization. Yucatec Maya cthnobiology agrees with contemporary international biological science in many respects, almost all of them highly specific, pragmatic and observational. It differs in many other respects, most of them highly inferential and cosmological. One may tentatively conclude that common observation of everyday matters is more directly affected by interaction with the nonhuman environment than is abstract deductive reasoning. but that social factors operate at all levels. Key words: Yucatec Maya, ethnoornithology, science wars, philosophy ofscience, Yucatan Peninsula RESUMEN.-EI EI conocimiento es una construcci6n social, pero los humanos pueden aprender mucho ce sus alrededores. Discursos recientes sobre "ciencia" incluyen posiciones extremos; algunos proponen que "ciencia" es arbitrario, otros proponen que "ciencia" es verdad absoluto. Seria posible conocer mucho si investiguemos el conocimiento biol6gico de una cultura, muy difcrente, con una historia larga de alta civilizaci6n. EI conodrniento etnobiol6gico de los Yucatecos conformc, mas 0 menos, con la sciencia contemporanea internacional, especial mente en detallas dcrivadas de la experiencia pragmatica. Pero, el es deferente en otros respectos-Ios que derivan de cosmovisi6n 0 de inferencia logical. -

Roadrunner Fact Sheet

Roadrunner Fact Sheet Common Name: Roadrunner Scientific Name: Geococcyx Californianus & Geococcyx Velox Wild Status: Not Threatened Habitat: Arid dessert and shrub Country: United States, Mexico, and Central America Shelter: These birds nest 1-3 meters off the ground in low trees, shrubs, or cactus Life Span: 8 years Size: 2 feet in length; 8-15 ounces Details The genus Geococcyx consists of two species of bird: the greater roadrunner and the lesser roadrunner. They live in the arid climates of Southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central America. Though these birds can fly, they spend most of their time running from shrub to shrub. Roadrunners spend the entirety of their day hunting prey and dodging predators. It's a tough life out there in the wild! These birds eat insects, small reptiles and mammals, arachnids, snails, other birds, eggs, fruit, and seeds. One thing that these birds do not have to worry about is drinking water. They intake enough moisture through their diet and are able to secrete any excess salt build-up through glands in their eyes. This adaptation is common in sea birds as their main source of hydration is the ocean. The fact that roadrunners have adapted this trait as well goes to show how well they are suited for their environment. A roadrunner will mate for life and will travel in pairs, guarding their territory from other roadrunners. When taking care of the nest, both male and female take turns incubating eggs and caring for their young. The young will leave the nest after a couple weeks and will then learn foraging techniques for a few days until they are left to fend for themselves. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Sonoran Joint Venture Bird Conservation Plan Version 1.0

Sonoran Joint Venture Bird Conservation Plan Version 1.0 Sonoran Joint Venture 738 N. 5th Avenue, Suite 102 Tucson, AZ 85705 520-882-0047 (phone) 520-882-0037 (fax) www.sonoranjv.org May 2006 Sonoran Joint Venture Bird Conservation Plan Version 1.0 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Acknowledgments We would like to thank all of the members of the Sonoran Joint Venture Technical Committee for their steadfast work at meetings and for reviews of this document. The following Technical Committee meetings were devoted in part or total to working on the Bird Conservation Plan: Tucson, June 11-12, 2004; Guaymas, October 19-20, 2004; Tucson, January 26-27, 2005; El Palmito, June 2-3, 2005, and Tucson, October 27-29, 2005. Another major contribution to the planning process was the completion of the first round of the northwest Mexico Species Assessment Process on May 10-14, 2004. Without the data contributed and generated by those participants we would not have been able to successfully assess and prioritize all bird species in the SJV area. Writing the Conservation Plan was truly a group effort of many people representing a variety of agencies, NGOs, and universities. Primary contributors are recognized at the beginning of each regional chapter in which they participated. The following agencies and organizations were involved in the plan: Arizona Game and Fish Department, Audubon Arizona, Centro de Investigación Cientifica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada (CICESE), Centro de Investigación de Alimentación y Desarrollo (CIAD), Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP), Instituto del Medio Ambiente y el Desarrollo (IMADES), PRBO Conservation Science, Pronatura Noroeste, Proyecto Corredor Colibrí, Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT), Sonoran Institute, The Hummingbird Monitoring Network, Tucson Audubon Society, U.S. -

Mexico Chiapas 15Th April to 27Th April 2021 (13 Days)

Mexico Chiapas 15th April to 27th April 2021 (13 days) Horned Guan by Adam Riley Chiapas is the southernmost state of Mexico, located on the border of Guatemala. Our 13 day tour of Chiapas takes in the very best of the areas birding sites such as San Cristobal de las Casas, Comitan, the Sumidero Canyon, Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Tapachula and Volcan Tacana. A myriad of beautiful and sought after species includes the amazing Giant Wren, localized Nava’s Wren, dainty Pink-headed Warbler, Rufous-collared Thrush, Garnet-throated and Amethyst-throated Hummingbird, Rufous-browed Wren, Blue-and-white Mockingbird, Bearded Screech Owl, Slender Sheartail, Belted Flycatcher, Red-breasted Chat, Bar-winged Oriole, Lesser Ground Cuckoo, Lesser Roadrunner, Cabanis’s Wren, Mayan Antthrush, Orange-breasted and Rose-bellied Bunting, West Mexican Chachalaca, Citreoline Trogon, Yellow-eyed Junco, Unspotted Saw-whet Owl and Long- tailed Sabrewing. Without doubt, the tour highlight is liable to be the incredible Horned Guan. While searching for this incomparable species, we can expect to come across a host of other highlights such as Emerald-chinned, Wine-throated and Azure-crowned Hummingbird, Cabanis’s Tanager and at night the haunting Fulvous Owl! RBL Mexico – Chiapas Itinerary 2 THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Tuxtla Gutierrez, transfer to San Cristobal del las Casas Day 2 San Cristobal to Comitan Day 3 Comitan to Tuxtla Gutierrez Days 4, 5 & 6 Sumidero Canyon and Eastern Sierra tropical forests Day 7 Arriaga to Mapastepec via the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Day 8 Mapastepec to Tapachula Day 9 Benito Juarez el Plan to Chiquihuites Day 10 Chiquihuites to Volcan Tacana high camp & Horned Guan Day 11 Volcan Tacana high camp to Union Juarez Day 12 Union Juarez to Tapachula Day 13 Final departures from Tapachula TOUR MAP… RBL Mexico – Chiapas Itinerary 3 THE TOUR IN DETAIL… Day 1: Arrival in Tuxtla Gutierrez, transfer to San Cristobal del las Casas. -

Appendix S1. List of the 719 Bird Species Distributed Within Neotropical Seasonally Dry Forests (NSDF) Considered in This Study

Appendix S1. List of the 719 bird species distributed within Neotropical seasonally dry forests (NSDF) considered in this study. Information about the number of occurrences records and bioclimatic variables set used for model, as well as the values of ROC- Partial test and IUCN category are provide directly for each species in the table. bio 01 bio 02 bio 03 bio 04 bio 05 bio 06 bio 07 bio 08 bio 09 bio 10 bio 11 bio 12 bio 13 bio 14 bio 15 bio 16 bio 17 bio 18 bio 19 Order Family Genera Species name English nameEnglish records (5km) IUCN IUCN category Associated NDF to ROC-Partial values Number Number of presence ACCIPITRIFORMES ACCIPITRIDAE Accipiter (Vieillot, 1816) Accipiter bicolor (Vieillot, 1807) Bicolored Hawk LC 1778 1.40 + 0.02 Accipiter chionogaster (Kaup, 1852) White-breasted Hawk NoData 11 p * Accipiter cooperii (Bonaparte, 1828) Cooper's Hawk LC x 192 1.39 ± 0.06 Accipiter gundlachi Lawrence, 1860 Gundlach's Hawk EN 138 1.14 ± 0.13 Accipiter striatus Vieillot, 1807 Sharp-shinned Hawk LC 1588 1.85 ± 0.05 Accipiter ventralis Sclater, PL, 1866 Plain-breasted Hawk LC 23 1.69 ± 0.00 Busarellus (Lesson, 1843) Busarellus nigricollis (Latham, 1790) Black-collared Hawk LC 1822 1.51 ± 0.03 Buteo (Lacepede, 1799) Buteo brachyurus Vieillot, 1816 Short-tailed Hawk LC 4546 1.48 ± 0.01 Buteo jamaicensis (Gmelin, JF, 1788) Red-tailed Hawk LC 551 1.36 ± 0.05 Buteo nitidus (Latham, 1790) Grey-lined Hawk LC 1516 1.42 ± 0.03 Buteogallus (Lesson, 1830) Buteogallus anthracinus (Deppe, 1830) Common Black Hawk LC x 3224 1.52 ± 0.02 Buteogallus gundlachii (Cabanis, 1855) Cuban Black Hawk NT x 185 1.28 ± 0.10 Buteogallus meridionalis (Latham, 1790) Savanna Hawk LC x 2900 1.45 ± 0.02 Buteogallus urubitinga (Gmelin, 1788) Great Black Hawk LC 2927 1.38 ± 0.02 Chondrohierax (Lesson, 1843) Chondrohierax uncinatus (Temminck, 1822) Hook-billed Kite LC 1746 1.46 ± 0.03 Circus (Lacépède, 1799) Circus buffoni (Gmelin, JF, 1788) Long-winged Harrier LC 1270 1.61 ± 0.03 Elanus (Savigny, 1809) Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 29/09/2021. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

New Information on the Late Pleistocene Birds from San Josecito Cave, Nuevo Leon, Mexico ’

A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY Volume 96 Number 3 The Condor96571-589 Q The Cooper Omithologkzd %cietY 1994 NEW INFORMATION ON THE LATE PLEISTOCENE BIRDS FROM SAN JOSECITO CAVE, NUEVO LEON, MEXICO ’ DAVID W. STEADMAN New York State Museum, The State Education Department, Albany, NY 12230 JOAQUIN ARROYO-CARRALES Museum of Texas Tech University,Lubbock, TX 79409 and Laboratorio de Paleozoologia,Subdireccion de ServiciosAcademicos, Instituto National de Antropologiae Historia, Mexico EILEEN JOHNSON Museum of Texas Tech University,Lubbock, TX 79409 A. FARIOLA GUZMAN Laboratorio de Paleozoologta,Subdireccibn de ServiciosAcademicos, Instituto National de Antropologiiae Historia, Mexico Abstract. We report 90 bird bones representing 18 speciesfrom recent excavations at San Josecito Gave, Nuevo Le6n, Mexico. The new material increasesthe avifauna of this rich late Pleistocenelocality from 52 to 62 species.Eight of the 10 newly recorded taxa are extant; each is either of temperate rather than tropical affinities (such as the American Woodcock Scolopax minor and Pinyon Jay Gymnorhinuscyanocephalus) or is very wide- spreadin its modem distribution. The two extinct taxa are a stork (Ciconia sp. or Mycteria sp.) and Geococcyxcalifornianus conklingi, a large temporal subspeciesof the Greater Road- runner. In this region of the Sierra Madre Oriental (about lat. 24”N, long. lOO”W, elev. 2,000-2,600 m). the late Pleistocene avifauna was a mixture of speciesthat to&y prefer coniferous or pine-oak forests/woodlands,grasslands/savannas, and wetlands. As with var- ious late Pleistoceneplant and mammal communities of the United Statesand Mexico, no clear modem analog exists for the late Pleistoceneavifauna of San JosecitoCave. Key words: Late Pleistoceneavzfaunas; Mexico; historicalbiogeography; extinct species; temperate/tropicaltransition. -

Fauna from the Lagartero Basurero, Chiapas, Mexico Kristin L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Identifying Social Drama in the Maya Region; Fauna from the Lagartero Basurero, Chiapas, Mexico Kristin L. Koželsky Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IDENTIFYING SOCIAL DRAMA IN THE MAYA REGION; FAUNA FROM THE LAGARTERO BASURERO, CHIAPAS, MEXICO By KRISTIN L. KOŽELSKY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2005 Copyright © 2005 Kristin L. Koželsky All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Kristin Koželsky defended on March 16, 2005. _________________________________ Mary E. D. Pohl Professor Directing Thesis _________________________________ Rochelle Marrinan Committee Member _________________________________ William A. Parkinson Committee Member _________________________________ Kitty Emery Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________________ Dean Falk, Chair, Department of Anthropology The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to offer gratitude to Dr. Mary Pohl, who made this thesis possible and provided thoughtful critique and support throughout this research and my studies at Florida State University. I would also like to extend special thanks to Dr. Rochelle Marrinan and Dr. William Parkinson whose critique and intellectual rigor have shaped my approach to archaeology. I would like to acknowledge Dr. Kitty Emery of the Florida Museum of Natural History, whose work has been influential for me; I appreciate her willingness to be a part of this thesis and the opportunity she has given me to work with the zooarchaeological collections at the Museum. -

Breeds on Islands and Along Coasts of the Chukchi and Bering

FAMILY PTEROCLIDIDAE 217 Notes.--Also known as Common Puffin and, in Old World literature, as the Puffin. Fra- tercula arctica and F. corniculata constitutea superspecies(Mayr and Short 1970). Fratercula corniculata (Naumann). Horned Puffin. Mormon corniculata Naumann, 1821, Isis von Oken, col. 782. (Kamchatka.) Habitat.--Mostly pelagic;nests on rocky islandsin cliff crevicesand amongboulders, rarely in groundburrows. Distribution.--Breedson islandsand alongcoasts of the Chukchiand Bering seasfrom the DiomedeIslands and Cape Lisburnesouth to the AleutianIslands, and alongthe Pacific coast of western North America from the Alaska Peninsula and south-coastal Alaska south to British Columbia (QueenCharlotte Islands, and probablyelsewhere along the coast);and in Asia from northeasternSiberia (Kolyuchin Bay) southto the CommanderIslands, Kam- chatka,Sakhalin, and the northernKuril Islands.Nonbreeding birds occurin late springand summer south along the Pacific coast of North America to southernCalifornia, and north in Siberia to Wrangel and Herald islands. Winters from the Bering Sea and Aleutians south, at least casually,to the northwestern Hawaiian Islands (from Kure east to Laysan), and off North America (rarely) to southern California;and in Asia from northeasternSiberia southto Japan. Accidentalin Mackenzie (Basil Bay); a sight report for Baja California. Notes.--See comments under F. arctica. Fratercula cirrhata (Pallas). Tufted Puffin. Alca cirrhata Pallas, 1769, Spic. Zool. 1(5): 7, pl. i; pl. v, figs. 1-3. (in Mari inter Kamtschatcamet -

Distribution of Overwintering Nearctic Migrants in the Yucatan Peninsula, I: General Patterns of Occurrence ’

The Condor9 1:515-544 0 The CooperOrnithological Society 1989 DISTRIBUTION OF OVERWINTERING NEARCTIC MIGRANTS IN THE YUCATAN PENINSULA, I: GENERAL PATTERNS OF OCCURRENCE ’ JAMES F. LYNCH SmithsonianEnvironmental Research Center, P.O. Box 28, Edgewater,MD 21037 Abstract. Point countsand mist-net surveyswere employed to studythe winter distri- bution of nearcticmigratory landbirds in Mexico’s YucatanPeninsula. Overwintering mi- grantscomprised 42 regularlyoccurring species, and accountedfor 30-58% (mean = 41%) of the individual birds encounteredin surveysof a wide rangeof natural and disturbed habitats.Some migratory species were encountered most frequently in pastures,agricultural fields,or brushysecond growth, but the main habitatfor many migrantswas tropical forest. Migratoryand residentspecies showed similar degreesof specializationwith respectto the successionalmaturity of their habitats,but residentswere more likely to specializeon particulartypes of matureforest. After mist-netcapture data werestandardized by rarefac- tion, therewere no statisticallysignificant differences in the ratio of migrantsto permanent residentsin habitatsthat ranged from pasture,through brushy old fields,to maturesemiever- greenforest. For any given number of captures,species richness of both migrantsand residentswas substantiallyhigher in mist-net samplesfrom pasturesand brushyold fields than in thosefrom maturesemievergreen forest. With few exceptions,nearctic migratory species that breed in mature temperate-zone forestoccurred both in forestand in brushysecond -

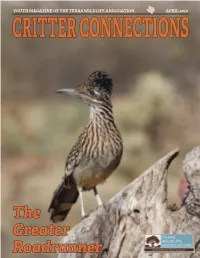

The Greater Roadrunner Cholla

YOUTH MAGAZINE OF THE TEXAS WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION APRIL 2018 CRITTER CONNECTIONS The Greater Roadrunner Cholla Cholla (Cylindropuntia imbricata or Opuntia imbricata), pronounced choy-yah, is a type of cactus found in dry, desert-type habitats in Texas and the southwestern United States. It is also known as tree cholla because it grows like a tree with a short trunk and branches. They are usually 3-8 feet in height and can be 3-4 feet wide. The stems of the plant are a greyish-green color and look like a braid or rope covered with spines. The second part of the scientific name, imbricata, means to have overlapping edges, which refers to the bumps or ridges on the branches. The spines are barbed, which means they have microscopic hooks on the tip like a fishhook. This means if you get a spine stuck in your hand it will stick just like a porcupine quill. Their yellow fruit grows at the end of the stems and looks similar to the branches of the plant but without the large spines. The fruits are hard and most animals and humans will not eat them, with the rare exception of some larger mammals, like cows. In the spring the cactus grows dark pink, or magenta, flowers that are about 5 centimeters or 2 inches wide. These flowers provide nectar for different insects like bees. When a stem falls onto the ground, it is able to grow roots and start a new plant. This makes it a fast spreading plant and can sometimes be considered a pest or weed.