The Politics of Iwi Voice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Outcomes Journey

TE WHĀNAU O WAIPAREIRA l ANNUAL REPORT 2015 -2016 2 #FUTUREMAKERS OUR OUTCOMES JOURNEY - TE WHĀ NAU O WAIPAREIRA #FUTUREMAKERS PERFORMANCE SUMMARY - l Annual Report 2015 – 2016 l Te Rārangi Upoko CONTENTS HE MIHI 2 NGĀ HUA O MATAORA OUR MATAORA OUTCOMES FRAMEWORK 2 OUTCOMES MEASUREMENT PILOT PĒPI AND TAMARIKI SERVICES 3 OUR WHĀNAU 5 6 OUR TAMARIKI 5 7 KORURE WHĀNAU – WHĀNAU TRANSFORMATION 8 REPORTING ON OUTCOMES 10 RANGATAHI OUTCOMES 11 OUR TAITAMARIKI SPEAK UP 12 SUPPORTING KORURE WHĀNAU - LIST OF SERVICES 14 HĀPORI MOMOHO - THRIVING COMMUNITIES 16 TE KĀHUI ORA O TĀMAKI COLLECTIVE IMPACT ACROSS THE TĀMAKI REGION 17 CRITICAL PARTNERSHIPS 20 SOCIAL VALUE AOTEAROA 20 HĀPAI TE HAUORA 21 WAITEMATA DISTRICT HEALTH BOARD 22 #FUTUREMAKERS MANA MĀORI 22 URBAN MAORI ADVANCEMENT NUMA 23 TE POU MATAKANA 25 WHĀNAU TAHI 27 DIRECTORY 28 OUR OUTCOMES JOURNEY - l Annual Report 2015 – 2016 l 1 He Mihi GREETINGS OUR MATAORA noho ana au ki te tara Waiatarua Ka hoki ngā whakaaro ki te wā o mua OUTCOMES FRAMEWORK EKi wana ki te wehi o ngā iwi Māori Ūhia ngā kanohi kei raro te whenua o te awa e are accountable to those that have papaku come before us, our communities and our Te waitohitohia rangatira ka roaka te ingoa Wwhānau. In 2013 we acknowledged this Waipareira! responsibility and laid out our vision for whānau in the “Whānau Future Makers, A 25 Year Outlook Ko te wehi ki a Ihowa ora o ngā mano. Kia Strategic Plan” māturuturu te tōmairangi o tōnā nui o tōnā atawhai ki runga i a tātau katoa. -

28927-Article Text-66259-1-10-20171212

Governed by Contracts: The Development of Indigenous Primary Health Services in Canada, Australia and New Zealand Josée G. Lavoie, PhD Candidate London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Health Policy Unit Abstract This paper is concerned with the emergence of Indigenous primary health care organizations in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. In Canada, the adoption of the 1989 Health Transfer Policy promoted the transfer of on-reserve health services from the federal government to First Nations. In Australia, Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Services first appeared in the 1970s because of community mobilization. It aims to provide some access to free health care to Aboriginal People. A more recent model, the Primary Health Care Access Program, aims at guaranteeing Aboriginal access to comprehensive primary health care services under the authority of Regional Aboriginal Health Boards. In New Zealand, Maori providers emerged because of the market-like conditions implemented in the 1990s. This study compares the policy and contractual environment put in place to support Indigenous health providers in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, using a case study approach. Results show that the contractual environment does not necessarily match declared policy objectives, especially where competitive models for accessing funding have been implemented. Key Words Primary health care, policy, self-determination, Indigenous People, health care financing, fourth sector INTRODUCTION needs of that group; and to promote their political as- This paper is concerned with the emergence of a pirations involving a renegotiation of their relation- fourth sector in Canada’s, Australia’s and New ship with the nation-state. Key features include in- Zealand’s health care systems. -

The Treaty Challenge: Local Government and Maori

THE TREATY CHALLENGE: LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND MAORI A Scoping Report :: 2002 :: Janine Hayward TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface....................................................................................................................................... 3 Part 1: Maori, Local Government, and the Treaty of Waitangi.......................................... 4 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................4 1.2 Local government, central government and Maori: early beginnings ....................... 5 1.3 Maori, Local Government and the Treaty: Local Government Reform 1980s.......... 7 1.4 Local government review 2001 and options for the future ...................................... 14 1.5 Conclusions .............................................................................................................. 20 1.6 Recommendations for further research .................................................................... 21 Part 2: Maori representation and Local Government........................................................ 22 2.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 22 2.2 Maori representation in local government: debate and reform ................................ 23 2.3 Who represents Maori / tangata whenua? ............................................................... 34 2.4 Conclusion............................................................................................................... -

The Waitangi Tribunal's WAI 2575 Report

HHr Health and Human Rights Journal The Waitangi Tribunal’s WAI 2575 Report: ImplicationsHHR_final_logo_alone.indd 1 10/19/15 10:53 AM for Decolonizing Health Systems heather came, dominic o’sullivan, jacquie kidd, and timothy mccreanor Abstract Te Tiriti o Waitangi, a treaty negotiated between Māori (the Indigenous peoples of Aotearoa) and the British Crown, affirmed Māori sovereignty and guaranteed the protection of hauora (health). The Waitangi Tribunal, established in 1975 to investigate alleged breaches of the agreement, released a major report in 2019 (registered as WAI 2575) about breaches of te Tiriti within the health sector in relation to primary care, legislation, and health policy. This article explores the implications of this report for the New Zealand health sector and the decolonial transformation of health systems. The tribunal found that the Crown has systematically contravened obligations under te Tiriti across the health sector. We complement the tribunal’s findings, through critical analysis, to make five substantive recommendations: (1) the adoption of Tiriti-compliant legislation and policy; (2) recognition of extant Māori political authority (tino rangatiratanga); (3) strengthening of accountability mechanisms; (4) investment in Māori health; and (5) embedding equity and anti-racism within the health sector. These recommendations are critical for upholding te Tiriti obligations. We see these requirements as making significant contributions to decolonizing health systems and policy in Aotearoa and thereby contributing to aspirations for health equity as a transformative concept. Heather Came is Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Health and Environment Sciences, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand. Dominic O’Sullivan is Associate Professor at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Charles Sturt University, Canberra, Australia. -

Aide-Ntentoire "TE MANA"TO WHAKAHIA"TO OR.A •

MINISTRY OF SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Aide-ntentoire "TE MANA"TO WHAKAHIA"TO OR.A • . • !• : l ~ • Meeting Date: 20 October 2015 Security Level: IN CONFIDENCE For: Han Anne Tolley, Minister for Social Development CC: File Reference: . J Meeting with Minister Flavell Meeting details Expected , ' . attendees Purpose of meeting and TPK have been discussingno"i.•.t"we·ciin work to.gether to better support the achievement of Whanau Ora outcomes. TPK has identified options for managing the potential transfer of funding and/or programmes and has been discussing these with their Minister. • That the funding and/or programmes be transferred to TPK, who will then administer it via contract with the Whanau Ora Commissioning Agencies (TPK's recommended approach). • That the funding and/or programmes be administered by MSD via contract with the Whanau Ora Commissioning Agencies. • That MSD retains administration of the funding and/or programmes via contract with current providers, but incorporates a Whanau Ora approach. In terms of timing, TPK has advised Minister Flavell that the potential transfer could take place: • in a phased manner, upon the expiry of current contracts (TPK's recommended approach), or Bowen State Building, Bowen Street, PO Box 1556, Wellington -Telephone 04-916 3300 - Facsimile 04-918 0099 • as soon as possible, through contract novation and transfer. TPK has also raised with their Minister the possibility of a more immediate transfer of the currently uncommitted Te Punanga Haumaru (TPH) funding (approximately $2.55 million) to the Whanau Ora Commissioning Agencies. Key issues In Its advice, TPK has highlighted three key issues that it · recommends Minister Flavell raise with you In the meeting. -

Friday, July 10, 2020 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI FRIDAY, JULY 10, 2020 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 LANDFILL BREACH STAR PAGES 3, 6-8, 10 ANOTHER WAKE-UP CALL OF GLEE COVID-19NEW 12-13, 20 PAGE 5 MISSING, • PBL Helen Clark heading Covid-19 response panel PRESUMED • Police to be posted at all managed isolation facilities DROWNED •PAGE Poor 3 response in US blamed on ‘anti-science bias’ • Covid-19 worldwide cases passes 12 million PAGE 12 SNOWDUST: Daytime maximum temperatures across Tairawhiti struggled to reach 11 degrees yesterday as the cold southerly brought a sprinkling of snow to the top of Mount Hikurangi — captured on camera by Sam Spencer. “We’re well and truly into the midst of winter now and yesterday sure would have felt like it,” said a MetService forecaster. “The dewpoint temperature (measure of moisture in air) was around zero degrees when the maximum air temperature was recorded. “The average daily maximum for Gisborne in July is around 15 degrees. “So it’s colder than average but it will need to drop a few more degrees to get into record books.” The district avoided the forecast frost overnight due to cloud cover, but MetService predicts 1 degree at Gisborne Airport tomorrow morning. by Matai O’Connor British High Commissioner to recovery,” she said. “Individuals New Zealand Laura Clarke, and organisations across TOITU Tairawhiti, a and Te Whanau o Waipareira Tairawhiti, including iwi, all collective of local iwi, have chief executive John Tamihere did a great job. organised a two-day summit to and Director-General of Health “We want to benchmark and reflect on the region’s response Dr Ashley Bloomfield. -

Roll of Members of the New Zealand House of Representatives, 1854 Onwards

Roll of members of the New Zealand House of Representatives, 1854 onwards Sources: New Zealand Parliamentary Record, Newspapers, Political Party websites, New Zealand Gazette, New Zealand Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), Political Party Press Releases, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, E.9. Last updated: 17 November 2020 Abbreviations for the party affiliations are as follows: ACT ACT (Association of Consumers and Taxpayers) Lib. Liberal All. Alliance LibLab. Liberal Labour CD Christian Democrats Mana Mana Party Ch.H Christian Heritage ManaW. Mana Wahine Te Ira Tangata Party Co. Coalition Maori Maori Party Con. Conservative MP Mauri Pacific CR Coalition Reform Na. National (1925 Liberals) CU Coalition United Nat. National Green Greens NatLib. National Liberal Party (1905) ILib. Independent Liberal NL New Labour ICLib. Independent Coalition Liberal NZD New Zealand Democrats Icon. Independent Conservative NZF New Zealand First ICP Independent Country Party NZL New Zealand Liberals ILab. Independent Labour PCP Progressive Coalition ILib. Independent Liberal PP Progressive Party (“Jim Anderton’s Progressives”) Ind. Independent R Reform IP. Independent Prohibition Ra. Ratana IPLL Independent Political Labour League ROC Right of Centre IR Independent Reform SC Social Credit IRat. Independent Ratana SD Social Democrat IU Independent United U United Lab. Labour UFNZ United Future New Zealand UNZ United New Zealand The end dates of tenure before 1984 are the date the House was dissolved, and the end dates after 1984 are the date of the election. (NB. There were no political parties as such before 1890) Name Electorate Parl’t Elected Vacated Reason Party ACLAND, Hugh John Dyke 1904-1981 Temuka 26-27 07.02.1942 04.11.1946 Defeated Nat. -

He Ara Takahinga DIRECTORY

He Ara Takahinga DIRECTORY A Directory of Services in Auckland to Support Whanau Ora Disclaimer Auckland District Health Board and Te Rūnanga O Ngāti Whātua provide this Directory as a service to the public. Auckland District Health Board and Te Rūnanga O Ngāti Whātua are not jointly or severally responsible for, and expressly disclaim all liability for, damages of any kind arising out of use, reference to, or reliance on any information contained within this Directory. While effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information contained herein, no guarantee is given that the information provided in this Directory is correct, complete, and up-to-date. Reference to third-party providers of services in this Directory does not constitute an endorsement by either Auckland District Health Board or Te Rūnanga O Ngāti Whātua of the parties or their products and services. He Mihi E ngā iwi, e ngā reo, e ngā karangarangatanga maha o te ao Tēnā koutou katoa Ka nui te mihi ki ō tātou tini mate i hinga atu nei, i hinga atu nā mai te Rerenga Wairua ki te Whanganui-a-tara whakawhiti ana Te Moana a Raukawa tae atu ki te Waipounamu whakawhiti atu ki te Rakiura mutu atu ki Rekohu. Haere atu koutou ki te putahitanga ō Rehua ki te huihuinga o te Kahurangi oti atu koutou ki reira e moe. Ka hoki mai kia tātou ngā morehu kanohi ora o rātou mā Tēnā ano tatou katoa Anei He Ara Takahinga i ruia mai i runga o Tamaki Makaurau whānui. Tirohia whanuitia i ngā wharangi e hiahia ai koe mo ngā rārangi korero katoa mou. -

Tekaraka09.Pdf

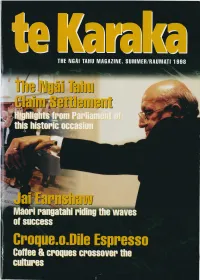

CUlJ ~ @ THE NGAI TAHU MAGAZINE Raumati I Summer 1998 ~ EDITOR Gabrielle Huria 9 CONTRIBUTORS Adrienne Anderson 8 Te Maire Tau editorial [M] Suzanne Ellison Ripeka Paraone GABRIELLE HURIA [M] Trudie Allan Tahu Potiki @J Hana O'Regan c:::::::J Nicola Walsh Nga mihi ate wa ki a koutou. 9 Dion Williams It's that time of the year again when everyone is frantic up until 25th Janyne Morrison @ December, after which time the whole nation slows down for three weeks. Paul White ~ Claire Kaahu White In that down time we have a chance to reflect on the year and for Ngc:i Rob lipa Tahu, the year has been monumental. The settlement process is now Anna Papa committed to our history and how we manage that settlement will be Moana lipa Kate Fraser critical to our future. Matiu Payne Mark Solomon is introduced as the new Kaiwhakahaere of Te ROnanga Virginia Innes-Jones Don Couch o Ngai Tahu. One of his first tasks was to be a signatory to the Ngai Tahu Claims Settlement Act. DESIGN Yellow Pencil PRINTING Liaise On In this edition of Te Karaka we have chosen a selection of pictures from the hikoi to Wellington for the third reading. Over 500 Ngai Tahu tribal PUBLISHER Ngai Tahu Publications Ltd PO Box 13 046 members packed the halls and gallery at Parliament to witness this Christchurch historic occasion. It was an emotional day for everyone including the Phone 03-366 4344 official Ngai Tahu photographer, Lloyd Park, who described the event as Fax 03-365 4424 "the most emotional shoot I have ever undertaken". -

Developing Co:Mpetency and Skills in Te Whanau 0 Waipareira Trust

DEVELOPING CO:MPETENCY AND SKILLS IN TE WHANAU 0 WAIPAREIRA TRUST Tony BuZZard with ERSF Project team ( Phillip Copper, Kathryn Hawes, Roberta Hill and Ken Wilson) Abstract Te Whanau o Waipareira Trust provides a large range of health, education, social, justice, economic and employment services to its predominantly West Auckland Maori constituency. It operates over a large number of sites and uses a wide range ofnetworks , alliances andjoint ventures to deliver its services. It's external environment, like many other New Zealand organisations, is characterised by rapid change and uncertainty. This paper is a preliminary analysis ofsome ofthe cultural and structural features ofWaipareira and the ski/ling strategies it undertakes to survive in its environment. Te Whanau o Waipareira Trust is the fourth case study of the FRST funded "Economic Restructuring and Skills Formation" project undertaken by WEB Research. Increasingly organisations in New Zealand are having to groups and networks representing West Auckland maori up survive in conditions of rapid change and uncertainty. In to this time was formalised and consolidated under the such an environment, what are the skilling strategies that umbrella of the Waipareira Trust in 1984. The decision to organisations undertake take and what are they key cultural change, from an loose open community forum to a trust, was and structural characteristics of these organisations? These made mainly to help it access funding and to find favour with are the two main objectives for the current research pro funding agencies (Hanna 1994). gramme undertaken by WEB Research titled Economic Restructuring and Skills Formation. Te Whanau o W aipareira Since 1991, under the current CEO' s direction, the trust has Trust is the fourth case study in this project. -

South Auckland Whānau Direct Area Population Snapshot

The South Auckland Whānau Direct Area Population Snapshot Locality Population Snapshot South Auckland Te Pou Matakana COMMISSIONING AGENCY KIA TU - KIA OHO - KIA MATAARA STAND TALL - STAND STRONG - STAND VIGILANT www.tepoumatakana.com Level 4, Whānau Centre I 6-8 Pioneer Steet, Henderson, Auckland, New Zealand Postal I PO Box 21 081, Henderson, Auckland 0650. New Zealand I Phone 0800 929 282 TE POU MATAKANA Te Pou Matakana COMMISSIONING AGENCY Te Pou Matakana KIA TU - KIA OHO - KIA MATAARA COMMISSIONING AGENCY STAND TALL - STAND STRONG - STAND VIGILANT Locality Population Snapshot South Auckland Produced by: Dr John Huakau Waipareira Tuararo Te Whānau o Waipareira, Research Unit. © 2014 Te Pou Matakana ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Any unauthorised copy, reprint or use of this material is prohibited. No part of this content may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without express written permission from Te Pou Matakana. ISBN 978-0-473-31577-1 JluyJuly 2014 Table of Contents Te Pou Matakana KIA TU - KIA OHO - KIA MATAARA COMMISSIONING AGENCY STAND TALL - STAND STRONG - STAND VIGILANT SECTION 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 Introduction...................................................................................................................................3 Demographics ..............................................................................................................................3 Socioeconomics Status -

Whānau Ora Annual Summary Report: 1 July 2016

Whānau Ora Annual Summary Report 1 July 2016 – 30 June 2017 Whakataukī Ma te huruhuru, ka rere te manu Adorn the bird with feathers so it can fly Cover photo: Sachko Shimamoto (left), Cinnimon Ratima (middle) and Lyka Rose (right) at a pre-Christmas whānau well-being day hosted by Te Waka Tapu in Christchurch. Photo credit: Madison Henry. Contents Te Puni Kōkiri Chief Executive Foreword 5 Executive Summary 7 Section 1 11 Introduction 11 1.1 What is Whānau Ora? 11 1.2 Purpose of the report 14 1.3 Whānau Ora delivery model 14 1.4 Measuring Whānau Ora 19 Section 2 21 2016/17 Whānau Ora expectations and achievements 21 2.1 What priorities were set for Whānau Ora in 2016/17? 22 2.2 What was achieved for Whānau Ora in 2016/17? 24 2.2.1 Te Pou Matakana 25 2.2.2 Te Pūtahitanga o Te Waipounamu 49 2.2.3 Pasifika Futures 71 2.2.4 Whānau Ora Partnership Group 87 Appendix 1 89 Whānau Ora Outcomes Framework: Empowering Whānau into the Future 90 Appendix 2 92 Glossary of Māori terms 92 Te Puni Kōkiri – Whānau Ora Annual Summary Report – 1 July 2016–30 June 2017 1 List of figures Figure 1: Moving from a traditional service delivery approach to a whānau-centred approach 11 Figure 2: Whānau Ora Commissioning Model 15 Figure 3: Whānau engaged with Te Pou Matakana during 2016/17 28 Figure 4: Ethnicity of whānau engaged with Te Pou Matakana during 2015/16 and 2016/17 29 Figure 5: Gender of whānau engaged with Whānau Direct during 2016/17 29 Figure 6: Age breakdown of whānau supported by Whānau Direct during 2016/17 30 Figure 7: Top 10 uses of Whānau Direct