Marimbas in South African Schools: Gateway Instruments for the Indigenous African Music Curriculum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

The Characteristics of Trauma

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Music and Trauma in the Contemporary South African Novel“ Verfasser Christian Stiftinger angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2011. Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 344 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: UF Englisch Betreuer: Univ. Prof. DDr . Ewald Mengel Declaration of Authenticity I hereby confirm that I have conceived and written this thesis without any outside help, all by myself in English. Any quotations, borrowed ideas or paraphrased passages have been clearly indicated within this work and acknowledged in the bibliographical references. There are no hand-written corrections from myself or others, the mark I received for it can not be deducted in any way through this paper. Vienna, November 2011 Christian Stiftinger Table of Contents 1. Introduction......................................................................................1 2. Trauma..............................................................................................3 2.1 The Characteristics of Trauma..............................................................3 2.1.1 Definition of Trauma I.................................................................3 2.1.2 Traumatic Event and Subjectivity................................................4 2.1.3 Definition of Trauma II................................................................5 2.1.4 Trauma and Dissociation............................................................7 2.1.5 Trauma and Memory...……………………………………………..8 2.1.6 Trauma -

Brian Baldauff Treatise 11.9

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Percussion Music of Michael W. Udow: Composer Portrait and Performance Analysis of Selected Works Brian C. (Brian Christopher) Baldauff Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE PERCUSSION MUSIC OF MICHAEL W. UDOW: COMPOSER PORTRAIT AND PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS OF SELECTED WORKS By BRIAN C. BALDAUFF A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music 2017 Brian C. Baldauff defended this treatise on November 2, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: John W. Parks IV Professor Directing Treatise Frank Gunderson University Representative Christopher Moore Committee Member Patrick Dunnigan Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To Shirley. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document and degree would not have been possible without the support, guidance, and patience of numerous extraordinary individuals. My wife, Caitlin for her unwavering encouragement. Dr. John W. Parks IV, my major professor, Dr. Patrick Dunnigan, Dr. Christopher Moore, and Dr. Frank Gunderson for serving on my committee. All my friends and colleagues from The Florida State University, the University of Central Florida, the University of Michigan, West Liberty University, and the University of Wisconsin- Stevens Point for their advice and friendship. My parents Sharon and Joe, and all my family members for their love. -

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin To cite this version: Denis-Constant Martin. Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. African Minds, Somerset West, pp.472, 2013, 9781920489823. halshs-00875502 HAL Id: halshs-00875502 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00875502 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin AFRICAN MINDS Published by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West, 7130, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.co.za 2013 African Minds ISBN: 978-1-920489-82-3 The text publication is available as a PDF on www.africanminds.co.za and other websites under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, as long as it is attributed to African Minds and used for noncommercial, educational or public policy purposes. The illustrations are subject to copyright as indicated below. Photograph page iv © Denis-Constant -

Footprints on the Sands of Time;

FOOTPRINTS IN THE SANDS OF TIME CELEBRATING EVENTS AND HEROES OF THE STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM AND DEMOCRACY IN SOUTH AFRICA 2 3 FOOTPRINTS LABOUR OF LOVE IN THE SANDS OF TIME Unveiling the Nkosi Albert Luthuli Legacy Project in August 2004, President Thabo Mbeki reminded us that: “... as part of the efforts to liberate ourselves from apartheid and colonialism, both physically and mentally, we have to engage in the process of telling the truth about the history of our country, so that all of our people, armed with this truth, can confidently face the challenges of this day and the next. ISBN 978-1-77018-205-9 “This labour of love, of telling the true story of South Africa and Africa, has to be intensified on © Department of Education 2007 all fronts, so that as Africans we are able to write, present and interpret our history, our conditions and All rights reserved. You may copy material life circumstances, according to our knowledge and from this publication for use in non-profit experience. education programmes if you acknowledge the source. For use in publication, please Courtesy Government Communication and Information System (GCIS) obtain the written permission of the President Thabo Mbeki “It is a challenge that confronts all Africans everywhere Department of Education. - on our continent and in the Diaspora - to define ourselves, not in the image of others, or according to the dictates and Enquiries fancies of people other than ourselves ...” Directorate: Race and Values, Department of Education, Room 223, President Mbeki goes on to quote from a favourite 123 Schoeman Street, Pretoria sub·lime adj 1. -

Local Worlds

Local Worlds Rural Livelihood Strategies in Eastern Cape, South Africa Flora Hajdu Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 366 Linköping University, Department of Water and Environmental Studies Linköping 2006 Linköping Studies in Arts and Science • No. 366 At the Faculty of Arts and Science at Linköpings universitet, research and doctoral studies are carried out within broad prob- lem areas. Research is organized in interdisciplinary research environments and doctoral studies mainly in graduate schools. Jointly, they publish the series Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. This thesis comes from the Department of Water and Environmental Studies at the Tema Institute. Distributed by: Department of Water and Environmental Studies Linköping University 581 83 Linköping Flora Hajdu Local Worlds Rural Livelihood Strategies in Eastern Cape, South Africa Edition 1:1 ISBN 91-85523-25-9 ISSN 0282-9800 © Flora Hajdu and Department of Water and Environmental Studies Original front cover photos: Flora Hajdu View over Cutwini and workers at the Mazizi Tea Plantation Printed by: LiU-Tryck, Linköping 2006 ‘It’s not the kings and generals that make history, but the masses of the people; the workers, the peasants, the doctors, the clergy’ Nelson Mandela ‘None but ourselves can free our minds’ Bob Marley Contents List of Figures, Tables and Boxes..................................................................xi Abbreviations.............................................................................................. xiii South African Institutions -

South African Festivals in the United States: an Expression of Policies

South African Festivals in the United States: An Expression of Policies, Power and Networks DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Akhona Ndzuta, MA Graduate Program in Arts Administration, Education and Policy The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee: Karen E. Hutzel, Ph.D. Wayne P. Lawson, Ph.D. Margaret J. Wyszomirski, Ph.D., Advisor Copyright by Akhona Ndzuta 2019 Abstract This research is a qualitative case study of two festivals that showcased South African music in the USA: the South African Arts Festival which took place in downtown Los Angeles in 2013, and the Ubuntu Festival which was staged at Carnegie Hall in New York in 2014. At both festivals, South African government entities such as the Department of Arts and Culture (DAC), as well as the Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO) were involved. Due to the cultural, economic and other mandates of these departments, broader South African government policy interests were inadvertently represented on foreign soil. The other implication is that since South African culture was central to these events, it was also key to promoting these acultural policy interests. What this research sets out to do is to explore how these festivals promote the interests of South African musicians while furthering South African government interests, and how policy was an enabler of such an execution. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Oppenheimer Memorial Trust and the National Arts Council of South Africa for their generous funding in the first two years of my studies. -

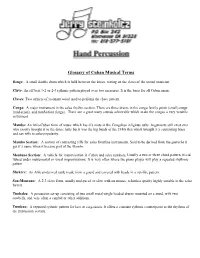

Glossary of Cuban Musical Terms

Glossary of Cuban Musical Terms Bongo: A small double drum which is held between the knees, resting on the claves of the seated musician. Clave: An off beat 3-2 or 2-3 rythmic pattern played over two measures. It is the basis for all Cuban music. Claves: Two strikers of resonant wood used to perform the clave pattern. Conga: A major instrument in the salsa rhythm section. There are three drums in the conga family- quinto (small) conga (mid-sized), and tumbadora (large). There are a great many sounds achievable which make the congas a very versitile instrument. Mambo: An Afro-Cuban form of music which has it’s roots in the Congolese religious cults. Arguments still exist over who exactly brought it to the dance halls but it was the big bands of the 1940s that which brought it’s contrasting brass and sax riffs to salsa popularity. Mambo Section: A section of contrasting riffs for salsa frontline instruments. Said to be derived from the guaracha it got it’s name when it became part of the Mambo. Montuno Section: A vehicle for improvisation in Cuban and salsa numbers. Usually a two or three chord pattern, it is ad- libbed under instrumental or vocal improvisations. It is very often where the piano player will play a repeated rhythmic pattern. Shekere: An African-derived rattle made from a gourd and covered with beads in a net-like pattern. Son-Montuno: A 2-3 clave form, usually mid-paced or slow with an intense, relentless quality highly suitable to the salsa format. -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

PELUANG EKSPOR INSTRUMEN MUSIK PERKUSI DI PASAR KANADA (Market Brief – ITPC Vancouver 2013)

PELUANG EKSPOR INSTRUMEN MUSIK PERKUSI DI PASAR KANADA (Market Brief – ITPC Vancouver 2013) INDONESIAN TRADE PROMOTION CENTER VANCOUVER 1300-1500 WEST GEORGIA ST. VANCOUVER, BC V6G 2Z6 CANADA KATA PENGANTAR Dengan mengucapkan syukur pada Tuhan Yang Maha Kuasa, ITPC Vancouver telah menyelesaikan Market Brief edisi Mei 2013 ini yang berjudul “Peluang Ekspor HS# 920600 – Instrumen Musik Perkusi (Percussion Musical Instruments) Di Pasar Kanada ”. Market Brief ini merupakan pembahasan singkat tentang potensi dan kondisi pasar produk Instrumen Musik Perkusi (Percussion Musical Instruments), di Kanada. Penulisan Market Brief ini mengacu pada “ Outline Market Intelligence & Market Brief ”, Departemen Perdagangan, tanggal 8 Maret 2011 di Hotel Borobudur, Jakarta. Pembuatan Market Brief merupakan bagian dari tugas ITPC di luar negeri yang merupakan informasi terkini tentang suatu produk di suatu negara, mencakup peraturan negara terakreditasi, potensi dan strategi penetrasi pasar, peluang dan hambatan, serta informasi penting yang diperlukan lainnya. Dengan demikian Market Brief ini diharapkan dapat membantu upaya meningkatkan pemasaran produk Instrumen Musik Perkusi (Percussion Musical Instruments) Indonesia dalam persaingan pasar Musical Instrument di Kanada. Semoga Market Brief ini bermanfaat bukan hanya bagi pengusaha Instrumen Musik Perkusi (Percussion Musical Instruments) nasional tapi juga pihak Pemerintah yang dalam hal ini selaku pembuat kebijakan. Terima kasih kami ucapkan atas perhatian, saran serta masukan untuk penyempurnaan Market Brief ini. Vancouver, Mei 2013 Indonesia Trade Promotion Center Wakil Kepala, Tengku Bayu Nasrul Sjah Market brief ITPC Vancouver - 2013 | - HS# 920600 : Instrumen Musik Perkusi (Percussion Musical Instruments) i D A F T A R I S I KATA PENGANTAR ……………………………………………… i DAFTAR ISI ……………………………….…………………………….. ii PETA NEGARA ……………………………………………..……….. iii BAB I. PENDAHULUAN …………………………………………………. 1 – 10 1.1. -

Belgium Raps Red Demand Aides from Congo

wi*i‘ wt ijfc-jQji^yas f r . si ' [ -BIGHT WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 7, 1*€0 / iUrntrir^iiti^^^tt^nins Average Dally Net Preee Rob The Weathw* *-5'|;%,"V\5'*'^‘''*'-' ■ ■'■ For the >!aiMI Feneeat ef .D. sT WaWNwr : Doe. s, uee OeMndy fair, eoUer tiiMitf; I 13,312 m d FrMay, enow flentei Member e l ttw AnaiS ever hUiy tMwttona. Law MMiM Dnrma ef Otrenlattoa Bear IB. Hlgji FrMay aear a#.r. ■* ' i M anchester^ A CUy of Villitge Charm YOUR STORE VOL. LXXX, NO. 68 (TWENTY-POUR PAGBft-IN TWO BECTIONS) MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, DECEMBER 8, 1960 (OtoaeUled JUIvaMeiag on Faga at) PRICE IHYS CBNTS OF VILEACE State News CHARM Military Rules J Roundup Belgium Raps Red Demand $200,000 Fire In Jewett City Savannakhet, Laos, Dec. 8ItPaOiet Lao forcos ringing tho capital were poiaod for attack. Jewett' City, Dec. 8 (A>)—-A (/P>—Right-wing rebel Imder Right-wing rebal 0«n. Phoumi Aides from Congo Gen. Phoumi Nosavan de 'ast spreading fire destroyed NoMvan, who ataged a bra<^k- the Jewett City Furniture Co. O clared today forces loyal to through on the Namkadinh River him staged the uprising in the front 100 mllea eaat of Vientiane early this morning. Wednesday, was reported advanc Fire officials said the malfunc STAMPS Laotian capital, Vientiane. He tion of an Oil burner might have ing on tha capital too. He had aaid the revolt against Pre regrouped his forces, recrossed the started the blaze. Their estiniate C ongolese THURSDAY ONLY! with all cash sales! THURSDAY ONLY! mier Souvanna Phouma’s re river, recaptured Pakadinh on the of the financial loss was $200,000, Blasts UN gime began in pre-dawn dark including the firm’s stock. -

Humanities Update 2016 HUMANITIES UPDATE Inside This Issue Faculty News: Greetings to Faculty 3 Dean’S Welcome 30 Student Bags National Excellence Award

december 2016 humanities update 2016 HUMANITIES UPDATE inside this issue Faculty news: Greetings to Faculty 3 Dean’s welcome 30 Student bags National Excellence Award 4 Workshop on illicit trade attracts top 30 Auf Wiedersehen Derick Musindi alumni from the journalists 31 Sixth Michaelis student makes 5 South meets north, thanks to Tierney Fellowship list research grant Dean of 35 South African College of Music 6 Same story, different country trains educators 7 Blending arts and commerce to enhance 36 Institute for Creative Arts launched Humanities IT career prospects 37 Knighthood for Professor Pather 10 PC donation to benefit local schools This is my final Humanities Update. As you know, I will leave the Faculty and UCT at the end 40 Victoria Mxenge: a homeless people’s of January 2017 to join the University of Fort Hare on 1 February. I will leave behind a place 11 CALDi develops tool for endangered struggle for dignity that I have called home for three years, a community of peers, colleagues and students language 43 2016 staff graduation stories who welcomed me at the end of 2013 and who have worked alongside me ever since. 12 African music tours Mozambique I will always be grateful for those encounters. But enough about that! 44 UCT Art Historian to teach at Oxford 13 Generous gift boosts UCT Opera Campaign 45 Innovative research on Indian I am very excited to share this year’s e-magazine, which is and Karin Murris (School of Education). Promoted to the cultural histories packed with staff and student success stories! The year 2016 rank of Associate Professor are: Dr Veronica Baxter (Drama); 14 Homegrown filmmakers make was a tumultuous year for UCT and the rest of higher education Dr Tanja Bosch (CFMS); Ms Jean Brundrit (Michaelis); Dr Joanne international waves in South Africa.