I Fagiolini: the Ache, the Bite and the Banger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stour Music 2021

STOUR MUSIC 2021 ‘Super-Excellent’ Martha McLorinan - mezzo-soprano Nicholas Mulroy - tenor Matthew Long - tenor Greg Skidmore - baritone Frederick Long - bass The 24 (University of York) English Cornett & Sackbut Ensemble Robert Hollingworth conductor Sponsored by James & Jane Loudon Saturday 19th June 6 & 8pm BOUGHTON ALUPH CHURCH Programme Giovanni Gabrieli (c.1514-1612) – Buccinate Joan de Cererols (1618-76) – Missa Batalla (Kyrie/Gloria) Alessandro Grandi (1586-1630) – O Intemerata Juan de Araújo (1646-1712) – Dixit Dominus a 11 Anon – Canzon a 6 Palestrina/Bovicelli – Ave verum corpus Edmund Hooper (c.1513-1621) – O God of Gods Heinrich Schütz (1585-72) – Fili mi Absalon Giovanni Gabrieli – In Ecclesiis (completed H.Keyte) Performers Martha McLorinan – mezzo-soprano Nicholas Mulroy, Matthew Long – tenor Greg Skidmore – baritone Frederick Long – bass William Lyons – Dulcian, curtal, shawm Nicholas Perry – Dulcian, curtal, shawm, cornett Lynda Sayce, Eligio Quinteiro – chitarrone, guitar James Johnstone, Catherine Pierron - organ English Cornett & Sackbut Ensemble Gawain Glenton, Conor Hastings – cornetto Emily White, Tom Lees, George Bartle, Miguel Tantos Sevillano –sackbut Adrian France, Adam Crighton – Bass sackbut Singers and ex-members from ‘The 24’ (University of York) Soprano Imogen Creedy, Anna Claire Golitizin, Eleanor Hunt, Ailsa Campbell, Eleanor Bray Alto Anna Palethorpe, Solomon Hayes, Helena Cooke, Finn Lacey Tenor Ed Lambert, Jack Harberd, James Wells Bass Freddie Foster, David Valsamidis, Ben Rowarth, Sam Gilliatt, George Cook, Phil Normand Programme Note In 1608 the great travel writer Thomas Coryat visited Venice, writing about the experience in his ‘Coryat’s Crudities’, notably recounting a musical entertainment at the confraternity of St Roch. ‘‘The third feast was upon Saint Roches day being Saturday and the sixth day of August, where I heard the best musicke that ever I did in all my life both in the morning and the afternoone, so good that I would willingly goe an hundred miles afoote at any time to heare the like. -

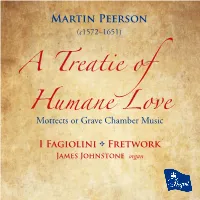

Martin Peerson (C1572–1651)

Martin Peerson (c1572–1651) A Treatie of HMottuectms or aGranve eCh amLber Mouvsic e I Fagiolini E Fretwork James Johnstone organ Martin Peerson (c1572–1651) MotteActs Tor eGartaivee oCfh Hamubmera Mneu sLiqouve e (1630) I Fagiolini E Fretwork James Johnstone organ 1 Love, the delight First part full 3:32 2 Beautie her cover is Second part full 3:04 3 Time faine would stay Third part verse 1:46 4 More than most faire First part full 3:12 5 Thou window of the skie Second part full 2:57 6 You little starres First part verse 1:04 7 And thou, O Love Second part verse 3:04 8 O Love, thou mortall speare First part full 2:52 9 If I by nature Second part full 2:30 10 Cupid, my prettie boy verse 2:52 11 Love is the peace verse 2:43 12 Selfe pitties teares full 3:48 13 Was ever man so matcht with boy? verse 2:21 14 O false and treacherous probabilitie verse 4:08 15 Man, dreame no more First part verse 1:43 16 The flood that did Second part verse 3:40 16 bis When thou hast swept Third part verse 17 Who trusts for trust First part full 3:40 18 Who thinks that sorrows felt Second part full 2:35 19 Man, dreame no more full 4:33 20 Farewell, sweet boye verse 3:01 21 Under a throne full 3:37 22 Where shall a sorrow First part verse 2:01 23 Dead, noble Brooke Second part verse 1:59 24 Where shall a sorrow (a6) First part full 2:48 25 Dead, noble Brooke (a6) Second part full 3:22 Editions by Richard Rastall: Martin Peerson, Complete Works IV: Mottects or Grave Chamber Musique (1630) (Antico Edition, 2012) -2- Martin Peerson and the publication of Grave Chamber Musique (1630) Martin Peerson’s second songbook, Mottects or Grave Chamber Musique , is known as a work of historical importance, but its musical and poetical importance is still unrecognised. -

Download Booklet

THE SUNLIGHT ON THE GARDEn INTRODUCTION Some thoughts around by Clare Wilkinson the words and the music THE SONGS OF STEPHEN WILKINSON (b.1919) (not following programme order) My father’s music has been part of my awareness by Stephen Wilkinson 1 Grantchester James Gilchrist tenor, Anna Markland piano [5.34] from my earliest days. Despite being very 2 Proud Songsters Mhairi Lawson soprano, Ian Buckle piano [1.28] varied (it spans 80 years), it has a particular The Sunlight on the Garden lies somewhere in 3 At the Manger Clare Wilkinson mezzo-soprano, Ian Buckle [4.08] language which is all his own; a unique voice, the middle of an output of songs spanning most 4 Joly Jankyn Clare Wilkinson, Ian Buckle [3.13] yet deeply rooted in the English song tradition of a rather long lifetime. It evokes World War 2, 5 Eternal Summer Matthew Brook bass, Anna Markland piano [2.22] of Finzi, Gurney and Quilter. On becoming an a real watershed for me, and I have allowed 6 Winter Snow Mhairi Lawson, Ian Buckle [1.05] adult and a musician myself I understood its myself a hint of the wail of an air-raid siren and 7 Chapels James Gilchrist, Anna Markland [3.04] quality, and decided that it ought to be known a bomb-drop. 8 Heaven Clare Wilkinson, Ian Buckle [5.53] more widely. This, combined with my father’s 9 The Hour-Glass Mhairi Lawson, Ian Buckle [2.01] natural humility, has led me to be the one MacNeice expresses man’s traditional complaint, 0 Come away, Death James Gilchrist, Anna Markland [3.23] who champions his work. -

How Like an Angel (U.S

10-22 Angel_GP 10/7/14 3:02 PM Page 1 Wednesday–Friday Evenings, October 22–24, 2014, at 7:30 Post-performance discussion with Robert Hollingworth, Yaron Lifschitz, and Ara Guzelimian on Thursday, October 23 How Like an Angel (U.S. premiere) Created by Yaron Lifschitz and Robert Hollingworth Circa Yaron Lifschitz, Director I Fagiolini Robert Hollingworth, Director This performance is approximately 70 minutes long and will be performed without intermission. Please join the artists for a White Light Lounge immediately following the performance. (Program continued) The White Light Festival is sponsored by Time Warner Inc. Generous support for the White Light Festival presentation of How Like an Angel is provided by The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. These performances are made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. James Memorial Chapel, Please make certain all your electronic devices Union Theological Seminary are switched off. WhiteLightFestival.org 10-22 Angel_GP 10/7/14 3:02 PM Page 2 Endowment support is provided by the American Upcoming White Light Festival Events: Express Cultural Preservation Fund. Friday–Sunday, October 24–26, MetLife is the National Sponsor of Lincoln Center. in the Walter Reade Theater White Light on Film: The Decalogue Movado is an Official Sponsor of Lincoln Center. Krzysztof Kie slowski , Director The complete ´cycle of 10 films is screened over a United Airlines is the Official Airline of Lincoln weekend. Center. Introduced by Annette Insdorf on October 24 at 7:30 Presented in association with the Film Society of WABC-TV is the Official Broadcast Partner of Lincoln Center Lincoln Center. -

Candlemas in Renaissance Rome Le Divin Arcadelt

CHANDOS early music LE DIVIN ARCADELT De Silva • PaleStrina Candlemas in Renaissance Rome MUSICA CONTEXTA with The English Cornett and Sackbut Ensemble © Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Photo & Arts Music © Lebrecht Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Le Divin Arcadelt: Candlemas in Renaissance Rome premiere recordings, except* Jacques Arcadelt (c. 1507 – 1568) 1 Pater noster 6:01 Motet 2 Hodie beata virgo Maria 3:23 Motet Chant 3 Suscepimus, Deus 3:16 Introitus Jacques Arcadelt 4 Kyrie from Missa ‘Ave, Regina caelorum’ 4:21 5 Gloria from Missa ‘Ave, Regina caelorum’ 5:24 Chant 6 Suscepimus, Deus 1:09 Graduale 3 Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (c. 1525 – 1594) 7 Senex puerum portabat* 7:31 Motet Jacques Arcadelt 8 Credo from Missa ‘Ave, Regina caelorum’ 9:18 Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina 9 Diffusa est gratia* 2:42 Offertory Chant 10 Nunc dimittis 2:11 Tractus Jacques Arcadelt 11 Sanctus from Missa ‘Ave, Regina caelorum’ 5:41 4 Chant 12 Responsum accepit Simeon 0:55 Communio Andreas de Silva (c. 1475 / 80 – c. 1530) 13 Inviolata, integra et casta es Maria 5:29 Motet Jacques Arcadelt 14 Agnus Dei from Missa ‘Ave, Regina caelorum’ 4:57 Andreas de Silva 15 Ave, Regina caelorum 5:44 Motet TT 68:14 Musica Contexta Simon Ravens director with The English Cornett and Sackbut Ensemble 5 Musica Contexta soprano Stephen Shellard Leonora Dawson-Bowling Andra Patterson alto Simon Lillystone Samir Savant Peter North tenor Patrick Allies Andrew Hope Simon Ravens bass Chris Hunter Philip Pratt Edmund Saddington 6 The English Cornett and Sackbut Ensemble -

13Th–29Th July 2018

13 th –29 th July 2018 BOOKING DETAIlS SuMMARY OF EvENTS FRIDAY 13Th JulY 19 8PM 39 8PM GENERAl BOOKING AND BOx OFFIcE 1 10AM choir of King’ s college, cambridge Sheku Kanneh-Mason (cello) OPEN FROM ThuRSDAY 12 Th APRIl Pre-concert talk Ampleforth Abbey Isata Kanneh-Mason (piano) St Mary’s Church, Birdsall The Long Gallery, Castle Howard 2 11AM ThuRSDAY 19Th JulY For a booking form, further booking details and booking terms please see pages 35–38 The chamber music of 20 10AM WEDNESDAY 25Th JulY or visit our website Antoní n Dvo řá k 1 Pre-concert talk 40 11AM St Mary’s Church, Birdsall Pickering Parish Church coffee concert 3 6PM 21 11AM Duncombe Park Royal Northern Sinfonia The chamber music of 41 7PM Hovingham Hall Antoní n Dvo řá k4 Robert hollingworth in conversation Pickering Parish Church Church of St Martin-on-the-Hill, POST SATuRDAY 14Th JulY 22 5.30PM Scarborough (can be received anytime, but dealt with according to Priority/General Booking dates ) 4 11AM chi-chi Nwanoku in conversation 42 8PM Young Artist Platform 1 Castle Howard Sacred and Profane: The Other Vespers Ryedale Festival Box Office, Memorial Hall, Potter Hill, Pickering, YO18 8AA St Oswald ’s Church, Sowerby 23 7PM Church of St Martin-on-the-Hill, 5 2PM Triple concert Scarborough PhONE (FROM 12 Th APRIl) Festival Masterclass: Brass Castle Howard Helmsley Arts Centre ThuRSDAY 26Th JulY 6 6PM 01751 475777 FRIDAY 20Th JulY 43 11AM Mozart – così fan tutte 24 2PM Soli Deo Gloria 2 IN PERSON (FROM 12 Th APRIl) Ryedale Festival Opera (with picnic Judith Weir in conversation St Lawrence ’s Church, York interval). -

I Fagiolini Barokksolistene Robert Hollingworth Director

I Fagiolini Barokksolistene Robert Hollingworth director CHAN 0760 CHANDOS early music © Graham Slater / Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Bust of Claudio Monteverdi by P. Foglia, Cremona, Italy 3 4 Zefiro torna, e ’l bel tempo rimena 3:29 (1567 – 1643) Claudio Monteverdi from Il sesto libro de madrigali (1614) Anna Crookes, Clare Wilkinson, Robert Hollingworth, Nicholas Mulroy, 1 Questi vaghi concenti 7:06 Charles Gibbs from Il quinto libro de madrigali (1605) Choir I: Julia Doyle, Clare Wilkinson, Richard Wyn Roberts, 5 Zefiro torna, e di soavi accenti 6:13 Nicholas Mulroy, Charles Gibbs from Scherzi musicali cioè arie, & madrigali in stil Choir II: Anna Crookes, William Purefoy, Nicholas Hurndall Smith, recitativo… (1632) Eamonn Dougan Nicholas Mulroy, Nicholas Hurndall Smith Strings: Barokksolistene Continuo: Eligio Quinteiro (chitarrone), Joy Smith, Continuo: Eligio Quinteiro (chitarrone), Joy Smith, Steven Devine Catherine Pierron (harpsichord) 2 T’amo, mia vita! 2:53 6 Ohimè, dov’è il mio ben? 4:44 from Il quinto libro de madrigali (1605) from Concerto. Settimo libro de madrigali (1619) Julia Doyle, Clare Wilkinson, Nicholas Mulroy, Eamonn Dougan, Charles Gibbs Julia Doyle, Clare Wilkinson Continuo: Joy Smith, Eligio Quinteiro (chitarrone) Continuo: Joy Smith, Eligio Quinteiro (chitarrone) 7 3 Ohimè il bel viso 4:51 Si dolce è ’l tormento 4:27 from Carlo Milanuzzi: from Il sesto libro de madrigali (1614) Quarto scherzo delle ariose (1624) Julia Doyle, Clare Wilkinson, Nicholas Mulroy, Eamonn Dougan, vaghezze… Charles Gibbs Nicholas -

Das Alte Werk' Titles Now Reduced by 30%

tel 0115 982 7500 fax 0115 982 7020 MARCH 2016 LIST See inside for valid dates Dear Customer, Two years after DG released their first, deluxe volume of recordings from Leonard Bernstein, the second volume has finally been announced! Due on 18th March, it is in the same LP-sized format as the initial box and will contain 64 CDs primarily focused on Romantic and 20th Century repertoire. It promises to be a very special collector’s item and is available at a discounted price for a short time. See p.2 for further details. Don’t forget that we also have a wide range of individual titles from Bernstein at reduced prices until 24th March (listed in February), including the aforementioned Boxset Volume 1 at just £76.95 (59 CDs + 1 DVD). March is looking strong for new releases, with recordings such as Elgar’s First Symphony from Barenboim (Decca), Honegger and Ibert’s joint work, ‘L’Aiglon’, from Nagano (Decca), Britten and Korngold Violin Concertos from Frang (Warner, already awarded Gramophone’s Disc of the Month in February), Elgar and Walton Cello Concertos from Isserlis (Hyperion), Bach from Jacobs (Harmonia Mundi), Mendelssohn’s arrangement of Handel’s ‘Israel in Egypt’ from The King’s Consort (Vivat), the next volume of Janacek from Gardner (Chandos), a recital of romantic violin sonatas from Ehnes (Onyx) and Bruckner from Jansons (RCO), to name but a few. Linn and Glossa are two excellent independent labels close to our hearts at Europadisc and we are very pleased to be able to offer discount on both throughout March and April. -

Thomas Tallis the Complete Works

Thomas Tallis The Complete Works Tallis is dead and music dies. So wrote William Byrd, Tallis's most distinguished pupil, capturing the esteem and veneration in which Tallis was held by his fellow composers and musical colleagues in the 16th century and, indeed, by the four monarchs he served at the Chapel Royal. Tallis was undoubtedly the greatest of the 16th century composers; in craftsmanship, versatility and intensity of expression, the sheer uncluttered beauty and drama of his music reach out and speak directly to the listener. It is surprising that hitherto so little of Tallis's music has been regularly performed and that so much is not satisfactorily published. This series of ten compact discs will cover Tallis's complete surviving output from his five decades of composition, and will include the contrafacta, the secular songs and the instrumental music - much of which is as yet unrecorded. Great attention is paid to performance detail including pitch, pronunciation and the music's liturgical context. As a result new editions of the music are required for the recordings, many of which will in time be published by the Cantiones Press. 1 CD 1 Music for Henry VIII This recording, the first in the series devoted to the complete works of Thomas Tallis, includes church music written during the first decade of his career, probably between about 1530 and 1540. Relatively little is known about Tallis’s life, particularly about his early years. He was probably born in Kent during the first decade of the sixteenth century. When we first hear of him, in 1532, he is organist of Dover Priory, a small Benedictine monastery consisting of about a dozen monks. -

William Byrd (C. 1540 – 1623) the Great Service in the Chapel Royal

William Byrd Engraving by Gerard van der Gucht (1696 / 97 – 1776) after drawing by Nicola Francesco Haym (1678 – 1729) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library William Byrd (c. 1540 – 1623) The Great Service in the Chapel Royal Matins 29:50 1 Constitues eos (prima pars) 1:11 Six-voice motet from Gradualia seu cantionum sacrarum, liber secundus (London, 1607) 2 Venite 5:13 3 Psalm 114. When Israel came out of Egypt 1:54 4 Te Deum 9:35 5 Benedictus 9:17 6 Anthem. Sing joyfully unto God our strength 2:38 Communion 11:34 7 Nunc scio vere (prima pars) 3:50 Six-voice motet from Gradualia seu cantionum sacrarum, liber secundus (London, 1607) 8 Kyrie 0:54 9 Prelude in C 1:14 Organ solo 10 Creed 5:34 3 Evensong 25:49 11 Hodie Simon Petrus 3:34 Six-voice motet from Gradualia seu cantionum sacrarum, liber secundus (London, 1607) 12 Psalm 47. O clap your hands together, all ye people 3:11 13 Magnificat 9:27 14 Verse in C 2:05 Organ solo 15 Nunc dimittis 5:02 16 Anthem. O Lord, make thy servant Elizabeth 2:27 TT 67:24 Musica Contexta Simon Ravens director with Steven Devine organ The English Cornett and Sackbut Ensemble 4 Musica Contexta soprano Andrea Cochrane Leonora Dawson-Bowling Lilla Grindlay Andra Patterson Lucy Taylor alto Ben Byram-Wigfield Simon Lillystone Peter North Samir Savant Stephen Shellard Mark Williams tenor Patrick Allies Andrew Hope Adrian Horsewood bass Robert Easting Chris Hunter Philip Pratt 5 The English Cornett and Sackbut Ensemble Gawain Glenton Sam Goble Tom Lees Emily White Andrew Harwood-White Adrian France cornetto Gawain -

Cambridge University Press 978-1

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-10808-0 — The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Historical Performance in Music Edited by Colin Lawson , Robin Stowell Index More Information Index Aaron, Pietro, 1, 106, 425, 580 Agricola, Martin, 18, 118, 241, 598, 627, 650, 655 Abbado, Claudio, 194 Musica instrumentalis deudsch, 19, 31, 448, Abel, Carl Friedrich, 1, 310, 648, 661 627 Abraham, Gerald, 95 Aguado, Dionisio, 276 Academy of Ancient Music (18th C), 2, 142, Agutter, Ralph, 598 188, 194, 293, 304, 306, 476, 512 Ahle, Johann Georg, 227 Academy of Ancient Music (20th C), 2, 192, Ahle, Johann Rudolph, 91 308, 347, 368, 398, 454–5, 562, 568, 588, Aichinger, Gregor, 253 698 Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, 193 Academy of St Martin in the Fields, 191 Akademische Bande, 249 Academy of Vocal Musick, 2 Al Ayre Español, 193 Accademia Bizantina, 193 Alamire, 197 Accademia Monteverdiana, 3, 82 Alard, Benjamin, 361 Accent, 4 Alard, Delphin, 19, 114, 171, 279, 653, 672 see also Accentuation Alarius Ensemble, 355 Accentuation, 73, 129, 212, 264, 292, 301, 339, Alberghi, Paolo, 112 371, 395, 416, 423, 531, 590, 610–11, 639, Albert, Eugène d’, 20 650, 697 Alberti bass, 28 Accordion, 42, 51, 496 Albinoni, Tomaso, 520, 668 Adam, Louis, 7, 343, 471, 625 Albrecht, Johann Lorenz, 8 Adams, John Albrechtsberger, Johann Georg, 20, 127, 341, Dharma at Big Sur, The, 669 343, 414, 443 Adams, Nathan, 312 Aldeburgh Festival, 94–5, 649 Adderley, Cannonball, 336 Aldrich, Putnam, 199 Addison, Joseph, 602 Alessandrini, Rinaldo, 193 Adler, Frédérique Guillaume, 68 Alexander, James, 656 Adler, Guido, 7 Alexandre père et fils Adlung, Jakob, 8, 137, 626 orgue-mélodium, 74 Adorno, Theodor W., 8, 12, 352 Alexanian, Diran, 94, 115, 122, 237, 272, 655 Aesthetic Theory, 8 Alfonso I, Duke of Ferrara, 241 Negative Dialectics, 8 Allegri, Gregorio Philosophy of New Music, 8 Miserere, 389 Aesthetics, 9, 102, 249, 326, 351, 373, 517, 520, 546, Allen, J. -

Performing Choirs

ACDA NATIONAL CONFERENCE MARCH 13-16, 2013 DALLAS, TEXAS PPERFORMINGERFORMING CCHOIRSHOIRS Arlington High School Colt Chorale Varsity Men Arlington Martin High School Chamber Singers Wednesday 8:00 pm Winspear Opera House (Gold track) Thursday 12:00 pm Meyerson Symphony Center (Gold track) Thursday 4:30 pm Meyerson Symphony Center (Blue Track) Wednesday 12:00 pm Winspear Opera House (Blue Track) The Martin Cham- ber Singers is a vocal ensemble comprised of the top students in the Martin choral program. The program has a total of 385 stu- dents involved. Among the thirty-seven mem- bers of Chamber Sing- ers, the students are The choral tradition at Arlington High School includes 320 involved in theatre, students in eight performing ensembles. The Varsity Men of band, orchestra, athlet- Colt Chorale range from fourteeen through eighteen years ics, student council, and of age. These young men are involved in AP and IB academic many different clubs on classes, ROTC, athletics, and many are employed in after- campus. Seventy-five school jobs. The Varsity Men are consistent UIL Sweepstakes percent of the students recipients and include many Texas All-State Choir members. in Chamber Singers take advanced placement courses. Colt Chorale has performed at the 2005 and 2009 Texas Martin Choirs performed at TMEA conventions in 1995, MEA Convention and the 2007 ACDA National Conference 2005, and 2008 and the 1997 and 2005 ACDA National in Miami. ACDA Conference. In 2006, Martin Chorale was selected by Carnegie Hall as one of three high school choirs to perform Dinah Menger is in her eighteenth year of at the National Youth Festival at Carnegie Hall.