Conference Report, “Pietism in Thuringia”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitteilungsblatt

AMTLICHES MITTEILUNGSBLATT Amtsblatt der Verwaltungsgemeinschaft Bad Tennstedt bestehend aus den Mitgliedsgemeinden: Bad Tennstedt, Ballhausen, Blankenburg, Bruchstedt, Haussömmern, Hornsömmern, Kirchheilingen, Klettstedt, Kutzleben, Mittelsömmern, Sundhausen, Tottleben und Urleben mit öffentlichen Bekanntmachungen der Mitgliedsgemeinden Jahrgang 28 | Nr. 8/2018 Freitag, den 27. April 2018 nächster Redaktionsschluss: Montag, den 30.04.2018 nächster Erscheinungstermin: Freitag, den 11.05.2018 Aus dem Inhalt Amtliche Bekanntmachungen - VG Bad Tennstedt - Bad Tennstedt - Sundhausen Veranstaltungen in der Ver- waltungsgemeinschaft - Maifeuer in Haussömmern - Maifeuer in Tottleben - 7. Crosslauf für Kinder in Sundhausen - „Anwassern“ im Kurpark Bad Tennstedt - Vogelstimmenwanderung in Mittelsömmern - Frühlingskonzert des Stad- torchesters Bad Tennstedt - Bücherzwerge in der Bib- liothek - Kurkonzerte in Bad Tennstedt - Release Party im Kosmo- laut Gemeindenachrichten - Frühjahrsputz in Bad Tennstedt - Danksagung an Jagdgenos- senschaft Haussömmern - Kita Kirchheilingen- Ein spannendes letztes Kinder- gartenjahr - Geburtstage im Mai Schulnachrichten - 1. Elternversammlung für die zukünftigen 1. Klassen der Sebastian- Kneipp-Grundschule Bad Tennstedt - Der Geografie-Wettbewer- bes Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn Gymnasiums - Die Pressekonferenz der Novalis-Regelschule - Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn- Gymnasium hat hinter die Kulissen des KiKA geschaut - Ferienrückblick der THEPRA Grundschule Kirchheilingen Redaktionsschluss - Vorlesewettbewerb am für das nächste -

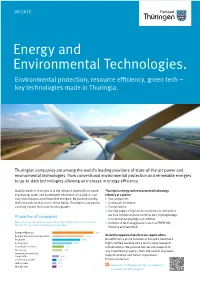

Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental Protection, Resource Efficiency, Green Tech – Key Technologies Made in Thuringia

09/2015 Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental protection, resource efficiency, green tech – key technologies made in Thuringia. Thuringian companies are among the world‘s leading providers of state-of-the-art power and environmental technologies: from conventional environmental protection and renewable energies to up-to-date technologies allowing an increase in energy efficiency. Quality made in Thuringia is in big demand, especially in waste Thuringia‘s energy and environmental technology processing, water and wastewater treatment, air pollution con- industry at a glance: trol, revitalization and renewable energies. By working closely > 366 companies with research institutions in these fields, Thuringia‘s companies > 5 research institutes can fully exploit their potential for growth. > 7 universities > leading engineering service providers in disciplines Proportion of companies such as industrial plant construction, hydrogeology, environmental geology and utilities (Source: In-house calculations according to LEG Industry/Technology Information Service, > market and technology leaders such as ENERCON, July 2013, N = 366 companies, multiple choices possible) Siemens and Vattenfall Seize the opportunities that our region offers. Benefit from a prime location in Europe’s heartland, highly skilled workers and a world-class research infrastructure. We provide full-service support for any investment project – from site search to project implementation and future expansions. Please contact us. www.invest-in-thuringia.de/en/top-industries/ environmental-technologies/ Skilled specialists – the keystone of success. Thuringia invests in the training and professional development of skilled workers so that your company can develop green, energy-efficient solutions for tomorrow. This maintains the competitiveness of Thuringian companies in these times of global climate change. -

Richtlinie Sonderprogramm Klimaschutz

Richtlinie des Freistaates Thüringen für die Zuweisungen an Gemeinden und Landkreise für Klimaschutz 1. Zuweisungszweck, Rechtsgrundlage 1.1 Der Freistaat Thüringen, vertreten durch die Ministerin für Umwelt, Energie und Naturschutz, gewährt Zuweisungen nach Maßgabe dieser Richtlinie auf der Grundlage des Thüringer Corona-Pandemie-Hilfefondsgesetzes und des Thüringer Klimagesetzes sowie des Thüringer Verwaltungsverfahrensgesetzes unter Anwendung der §§ 23 und 44 der Landeshaushaltsordnung (ThürLHO) sowie der hierzu erlassenen Verwaltungsvorschriften in den jeweils geltenden Fassungen. 1.2 Zweck der Zuweisung ist es, Investitionen von Gemeinden und Landkreisen für Klimaschutz nach § 7 Absätze 1 und 4 ThürKlimaG zu ermöglichen und damit gleichzeitig Hilfen für die Stabilisierung der kommunalen Haushalte und zum Erhalt der Leistungsfähigkeit nach § 2 Abs. 2 Punkt 8 Thüringer Corona-Pandemie- Hilfefondsgesetz im Bereich Klimaschutz zu leisten. Ziel der Investitionen sind kommunale Beiträge zur Klimaneutralität. 1.3 Ein Rechtsanspruch auf die Zuweisung besteht nicht. 2. Gegenstand der Zuweisung Gegenstand der Zuweisung sind Finanzhilfen für Investitionen im kommunalen Klimaschutz. 3. Zuweisungsempfänger Zuweisungsempfänger nach dieser Richtlinie sind die Thüringer Gemeinden und Landkreise. 4. Art und Umfang, Höhe der Zuweisung 4.1 Art und Form der Zuweisung, Finanzierungsart Die Zuweisung wird als nicht rückzahlbarer Zuschuss in Form einer Projektförderung als Festbetragsfinanzierung gewährt. 4.2 Verwendung Die Zuweisung kann für sämtliche Projektausgaben für Investitionen und die Vorbereitung solcher im kommunalen Klimaschutz im Sinne von §§ 4, 5, 7, 8 und 9 ThürKlimaG verwendet werden. Eine nicht abschließende Positivliste von möglichen Maßnahmen findet sich in Anlage 1 der Richtlinie. 4.3 Höhe der Zuweisung Die Höhe der Zuweisung bemisst sich für Gemeinden, Landkreise und kreisfreie Städte nach den Anlagen 2a, 2b und 2c dieser Richtlinie, soweit nicht nach Nr. -

Übersicht Der Philharmonischen Sommerkonzerte an Besonderen Orten

Übersicht der Philharmonischen Sommerkonzerte an besonderen Orten 25.06.2021 , 18 Uhr EISENACH in der Georgenkirche Eröffnungskonzert der Telemann-Tage „Zart gezupft und frisch gestrichen“ von Telemann zum jungen Mozart, mit der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach, Solovioline/Leitung Alexej Barchevitch, Solistin Natalia Alencova, Mandoline (Tickets 20,-, erm. 15 Euro, www.telemann-eisenach.de) 27.06., 04.07. und 11.07.2021 jeweils 16 Uhr BAD SALZUNGEN im Garten der Musikschule Bratschenseptett „Ars nova“ der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach Blechbläserquartett der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach Bläserquintett der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach (Eintritt frei, wir freuen uns über Spenden) 02.07.2021 19:30 Uhr EISENACH Landestheater Eisenach Eröffnungskonzert des Sommerfestivals des Landestheaters Eisenach mit dem Bläseroktett, Kontrabass und Schlagwerk der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach (www.landestheater-eisenach.de, Touristinfo Eisenach, www.eventim.de) 03.07. und 17.07.2021, 17 Uhr BAD LIEBENSTEIN / SCHLOSSPARK ALTENSTEIN "Hofmusik zur Zeit Georgs I. von Sachsen-Meiningen" mit der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach, Solovioline/Leitung Alexej Barchevitch "Auf die Harmonie gesetzt" - Liebensteiner Bademusik mit dem Bläseroktett der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach (Tickets über www.ticketshop-thueringen.de) 03.07. – 29.08.2021 SCHLOSSHOF OPEN AIR auf Schloss Friedenstein in Gotha mit verschiedenen Konzertprogrammen u.a. mit den Stargästen Ragna Schirmer und Martin Stadtfeld und vielen weiteren prominenten -

Historical Aspects of Thuringia

Historical aspects of Thuringia Julia Reutelhuber Cover and layout: Diego Sebastián Crescentino Translation: Caroline Morgan Adams This publication does not represent the opinion of the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung. The author is responsible for its contents. Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen Regierungsstraße 73, 99084 Erfurt www.lzt-thueringen.de 2017 Julia Reutelhuber Historical aspects of Thuringia Content 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia 2. The Protestant Reformation 3. Absolutism and small states 4. Amid the restauration and the revolution 5. Thuringia in the Weimar Republic 6. Thuringia as a protection and defense district 7. Concentration camps, weaponry and forced labor 8. The division of Germany 9. The Peaceful Revolution of 1989 10. The reconstitution of Thuringia 11. Classic Weimar 12. The Bauhaus of Weimar (1919-1925) LZT Werra bridge, near Creuzburg. Built in 1223, it is the oldest natural stone bridge in Thuringia. 1. The landgraviate of Thuringia The Ludovingian dynasty reached its peak in 1040. The Wartburg Castle (built in 1067) was the symbol of the Ludovingian power. In 1131 Luis I. received the title of Landgrave (Earl). With this new political landgraviate groundwork, Thuringia became one of the most influential principalities. It was directly subordinated to the King and therefore had an analogous power to the traditional ducats of Bavaria, Saxony and Swabia. Moreover, the sons of the Landgraves were married to the aristocratic houses of the European elite (in 1221 the marriage between Luis I and Isabel of Hungary was consummated). Landgrave Hermann I. was a beloved patron of art. Under his government (1200-1217) the court of Thuringia was transformed into one of the most important centers for cultural life in Europe. -

A Study on Connectivity and Accessibility Between Tram Stops and Public Facilities: a Case Study in the Historic Cities of Europe

Urban Street Design & Planning 73 A study on connectivity and accessibility between tram stops and public facilities: a case study in the historic cities of Europe Y. Kitao1 & K. Hirano2 1Kyoto Women’s University, Japan 2Kei Atelier, Yame, Fukuoka, Japan Abstract The purpose of this paper is to understand urban structures in terms of tram networks by using the examples of historic cities in Europe. We have incorporated the concept of interconnectivity and accessibility between public facilities and tram stops to examine how European cities, which have built world class public transportation systems, use the tram network in relationship to their public facilities. We selected western European tram-type cities which have a bus system, but no subway system, and we focused on 24 historic cities with populations from 100,000 to 200,000, which is the optimum size for a large-scale community. In order to analyze the relationship, we mapped the ‘pedestrian accessible area’ from any tram station in the city, and analyzed how many public facilities and pedestrian streets were in this area. As a result, we were able to compare the urban space structures of these cities in terms of the accessibility and connectivity between their tram stops and their public facilities. Thus we could understand the features which determined the relationship between urban space and urban facilities. This enabled us to evaluate which of our target cities was the most pedestrian orientated city. Finally, we were able to define five categories of tram-type cities. These findings have provided us with a means to recognize the urban space structure of a city, which will help us to improve city planning in Japan. -

Fahrplan RVG Gotha Gültig Ab 13.12.2015

Fahrplan RVG Gotha gültig ab 13.12.2015 860 Montag - Freitag s f s COT Gotha ZOB Steig 6 ab 4.55 5.55 6.25 6.25 7.25 8.00 10.00 12.00 12.55 13.55 15.00 15.55 16.55 18.00 20.00 20.55 Eisenach ab 4.10 6.47 12.13 13.11 15.11 16.13 20.13 21.13 Gotha Hbf. an 4.32 7.13 12.34 13.32 15.32 16.35 20.34 21.34 Erfurt Hbf. ab 4.30 5.55 5.55 7.00 12.12 14.12 15.30 16.12 17.30 20.12 21.13 Gotha Hbf. an 4.53 6.16 6.16 7.21 12.30 14.30 15.47 16.30 17.47 20.30 21.33 Gotha Hauptbahnhof Steig 1B ab 5.00 6.00 6.30 6.30 7.30 8.05 10.05 12.05 13.00 14.00 15.05 16.00 17.00 18.05 20.05 21.00 22.00 Gotha Lindenhügel/Tierpark 5.04 6.04 6.34 6.34 7.34 8.09 10.09 12.09 13.04 14.04 15.09 16.04 17.04 18.09 20.09 21.04 22.04 Gotha Friedensteinkaserne 5.06 6.06 6.36 6.36 7.36 8.11 10.11 12.11 13.06 14.06 15.11 16.06 17.06 18.11 20.11 21.06 22.06 Schwabhausen 5.11 6.11 6.41 6.41 7.41 8.16 10.16 12.16 13.11 14.11 15.16 16.11 17.11 18.16 20.16 21.11 22.11 Hohenkirchen 5.16 6.16 6.46 6.46 7.46 | | | 13.16 14.16 | 16.16 17.16 | | 21.16 22.16 Herrenhof Hohenkircher Str. -

Bürger-Informationsbroschüre Des Landkreis Gotha

& 1-& #&&- - - - & % % & * 0" "&* &- * *" ' &*- uǽ̅͑ȗ̔Ŀ͑̔LJɴʓǨ͑ʵɓ ΅˄ʵ uǽ̅͑ȗ̔˄̅ɴǽʵ̶ɴǽ̅͑ʵɓ uǽ̅͑ȗ̔΅˄̅LJǽ̅ǽɴ̶ǽʵǨǽ »͑ɓǽʵǨʓɴǖɥǽʵ ɴʵ Ǩǽʵ ȗ͖̅ êǖɥ͖ʓǽ̅ ɴʦ uɴʓǨ͑ʵɓ̔ʓǽɴ̶̔͑ʵɓǽʵ uǽ̅͑ȗ̔Ï̅ɴǽʵ̶ɴǽ̅ǽʵǨǽʵ uǽ̅͑ȗǽʵǣ Àǽ̅ʵɳ ͑ʵǨ ǔ˹͆Ƕ̈ʪ˹Ƙǔ˹ǔɘ̪ǔʛƾǔ jʪƧɉƺ ǔɘɲʪƧɉ Ę̅Ŀɴʵɴʵɓ̔ĺǽʵ̶̅͑ʦ ɘɹƾ͆ʛȷ̈ʌĄȾʛĄɉʌǔʛ CĄƧɉɲ˹ĄǶ̪ ɘʌ uÏÀĘĺ ʛĄƧɉ CĄƧɉɲʪʛΚǔ˓̪ ƾǔ˹ DĄ̪̈ȷǔΈǔ˹Ƙǔ ͑ʵǨ ɴʦ à̅˄ʊǽʌ̶ ȷǔʛ̪͆˹ Ƕ͋˹ ˹Ƙǔɘ̪ CĄƧɉɹĄȷǔ˹ɘ̪̈ º jÁÖwĬÁ?ÞÄ ǔ˹ɹǔƘǔʛ˲ ǔ˹͆Ƕ̈Ƕɘʛƾ͆ʛȷ ͆ʛƾ ˹Ƙǔɘ̪̈ɗ Òɘ̈Ƨɉɹǔ˹ƺ RʪɹΚƘǔĄ˹Ƙǔɘ̪ǔ˹ ǔ˹˓˹ʪƘ͆ʛȷ Ƕ͋˹ h͆ȷǔʛƾɹɘƧɉǔ Dē˹̪ʛǔ˹ƺ ͆ʛƾ *˹ΈĄƧɉ̈ǔʛǔ DĄ˹̪ǔʛƘĄ͆Έǔ˹ɲǔ˹ êǖɥ͑ʓʓĿʵǨɥǽɴʦ ɴʵ ĮĿʓ̶ǽ̅̔ɥĿ͑̔ǽʵ tǔ̪ĄɹɹƘĄ͆ǔ˹ƺ ¤Ƨɉ͆ɹǔ˹ȷēʛΚǔʛƾǔ˹ mǔ˹ʛʪ˹̪ Ƕ͋˹ Ąɹɹǔ tǔ̪ĄɹɹƘǔĄ˹Ƙǔɘ̪ǔ˹ ¤Ƨɉ͆ɹǶʪ˹ʌǔʛ uǽɓʓǽɴ̶ǽʵǨǽ ĿǖɥǨɴǽʵ̶̔ǽǣ Dǔ˹ē̪ǔΚ͆̈Ąʌʌǔʛ̈ǔ̪Κǔ˹ *˹ɹǔƘʛɘ̈ΈĄʛƾǔ˹͆ʛȷǔʛ ̈ΏƧɉʪɹʪȷɘ̈Ƨɉǔ˹ &ɘǔʛ̪̈ ͋˹ʪɲĄ͆ǶʌĄʛʛ̢ɗǶ˹Ą͆ƺ ǔ˹͆Ƕ̈ʪ˹ɘǔʛ̪ɘǔ˹ǔʛƾǔ ˹ʪɰǔɲ̪ǔ ¤ʪΚɘĄɹ˓ēƾĄȷʪȷɘ̈Ƨɉǔ˹ &ɘǔʛ̪̈ jĄ͆ǶʌĄʛʛ̢ɗǶ˹Ą͆ Ƕ͋˹ ʛȷǔƘʪ̪ǔ Κ͆˹ ˹ǔȷɘʪʛĄɹǔʛ ͋˹ʪɲʪʌʌ͆ʛɘɲĄ̪ɘʪʛƺ j͆ɹ̪͆˹ȷǔ̈ƧɉɘƧɉ̪ǔ *˹ȷʪ̪ɉǔ˹Ą˓ǔ̪͆ɘ̈Ƨɉǔ˹ ͋˹ʪɲ˹ĄǶ̪ ¤˓ʪ˹̪ ͆ʛƾ C͆ʛ &ɘǔʛ̪̈ ïǔ˹ɲē͆Ƕǔ˹ tʪ̪ʪ˓ēƾɘ̈Ƨɉǔ ǔ˹Ą̪͆ʛȷ tĄɹǔ˹ƺ Ą̪͆ǔʛɗ ͆ʛƾ Rǔɘɹ˓ēƾĄȷʪȷɘ̈Ƨɉǔ˹ |Ƙɰǔɲ̪Ƙǔ̈ƧɉɘƧɉ̪ǔ˹ &ɘǔʛ̪̈ RĄ͆̈Έɘ˹̪̈ƧɉĄǶ̪ǔ˹ƺ ¤ʪʛƾǔ˹˓ēƾĄȷʪȷɘ̈Ƨɉ RĄ͆̈Έɘ˹̪̈ƧɉĄǶ̪ǔ˹ɘʛ ȷǔ̈Ƨɉ͆ɹ̪ǔ̈ ǔ˹̈ʪʛĄɹ - 0*& "& *" '* & *- & *-& .& &* "* - ''*/&'* - '& * &*& 1-& &.- % & 1-& #&&- - - - & % % .'*& $ !!)( "* 2+),$ ,+(!2 2+),$ (),2! 000%"- '1 *&-% ""- '1 *&-% Grußwort des Landrates ausgeschilderte Wanderwege; auch für Freunde des Nordic Walking oder Radfahrer bieten sich beste Möglichkeiten in landschaftlich reizvoller Umgebung, beispielsweise in den „Fahner Höhen“ im Norden des Landkreises. Zugleich beherbergt der Landkreis Gotha einma- lige kulturhistorische -

Amtsblatt Vom 24.10.2019

Amtlicher Teil: DER LANDKREIS Bekanntmachung des Wahlleiters S. 2 Sitzungstermine der Ausschüsse S. 2 Satzung des Jugendhilfe-Ausschusses S. 3 Auslegung des Regionalplanes S. 4 Nichtamtlicher Teil: Stellenausschreibungen S. 10 AMTSBLATT Ausschreibung von Bauleistungen S. 13 Förderung für Gigabit-Breitband beantragt S. 19 Ausgabe vom 24. Oktober 2019 | 28. Jahrgang | Nr. 17 Einladung zum Friedensgebet S. 20 Sammlung: Die diesjährige Haus- und Straßensammlung des Volksbundes Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e. V. - Landesverband Thüringen - findet im Zeit- raum vom 28. Oktober bis 17. Novem- ber auch im Landkreis Gotha stattfinden. Auch in diesem Jahr bitten vor dem Volkstrauertag überall in Deutschland wieder hunderte freiwillige Helfer, Solda- ten sowie Reservisten der Bundeswehr auf den Straßen und an den Haustüren um einen Obolus für die Arbeit des Volks- bundes. Der 1919 gegründete Volksbund kümmert sich um die Erhaltung von etwa zwei Millionen Gräbern beider Weltkriege in 45 Ländern und setzt sich für die inter- | Über insgesamt 13 Spiel- und Bewegungsmöglichkeiten wie diese Kletteranlage, die Vanessa aus der nationale Verständigung ein. 7. Klasse ausprobiert, verfügt der neue Außenbereich. Einblicke: Am Samstag, 26. Oktober, Große Freude über Schulaußenbereich lockt der „Tag der offenen Firmen“ in die Landkreis investiert 760.000 Euro am Standort Breite Gasse Gothaer Unternehmen. Dann informiert man sich nicht am Messestand in bun- Gotha | Nach den Herbstferien war es die Tischtennisanlage fanden ihren festen ten Broschüren, sondern direkt in Pro- diese Woche endlich so weit: Die 129 Platz. Eine Garage für temporär genutzte duktions- und Lagerhallen, Büros oder Mädchen und Jungen des Förderzent- Spielzeuge sowie eine zeitgemäße Umzäu- Geschäftsräumen – ein echter Erlebnis- rums Lucas Cranach in Gotha können ab nung runden das Angebot ab. -

The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: a Study of Duty and Affection

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 6-1-1971 The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: A study of duty and affection Terrence Shellard University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Shellard, Terrence, "The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: A study of duty and affection" (1971). Student Work. 413. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/413 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE OF COBURG AND QUEEN VICTORIA A STORY OF DUTY AND AFFECTION A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Terrance She Ha r d June Ip71 UMI Number: EP73051 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Diss««4afor. R_bJ .stung UMI EP73051 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. -

Gesamtliste Bahnhofstraße 4 - 8 98527 Suhl Übersicht Erfassung Und Bewertung Touristischer Infrastrukturbedarfe in Der Rennsteigregion - Gesamtliste

Bitte vertraulich behandeln! Maßnahmekatalog zur Erfassung touristische Infrastrukturentwicklung IGR - gemeinnützige Infrastrukturgesellschaft Rennsteig mbH Gesamtliste Bahnhofstraße 4 - 8 98527 Suhl Übersicht Erfassung und Bewertung touristischer Infrastrukturbedarfe in der Rennsteigregion - Gesamtliste Projektgruppe A - Basisinfrastruktur Rennsteigregion A1 Anlegen von Aussichtspunkten (Aussichtsplateau) Berechnungsgrundlage: FA Oßwald AP Finsterberg 8.00m | 180.000,-€ Eingereicht GRW- TA Streckenabschnitt/Lage R-km Höhe in m Kostenschätzung (€) Abrechnung (€) Landkreis Gemeinde Bemerkung Produktmarke Anfragen TAB / Träger Steigerung des Erlebniswerts am Standort Alexanderturm - 1 Installation eine Beleuchtungsanlage 18 200.000,00 Wartburgkreis Ruhla Einzelprojekt Aktivregion Rstg. Anlage eines Aussichtspunktes aus dem alten 2 Feuerwachturm Clausberg 8 180.000,00 Wartburgkreis Gerstungen Einzelprojekt Aktivregion Rstg. Wildgehege Unterschönau (Aussichtspunkt) und Schmalkalden- Unterschönau (Steinbach- 3 Sitzgelegenheiten) 8 180.000,00 Meiningen Hallenberg) Einzelprojekt Aktivregion Rstg. 4 Aussichtsturm auf dem Gottlob 8 180.000,00 Gotha Friedrichroda Einzelprojekt Aktivregion Rstg. 5 Aussichtspunkt auf dem Ziegenberg 8 180.000,00 Gotha Waltershausen Einzelprojekt Aktivregion Rstg. 6 Aussichtsturm "Schwabhäuser Kopf" 8 180.000,00 Gotha Georgenthal Einzelprojekt Aktivregion Rstg. 7 Finsterbergturm (Umsetzung erfolgt bereits) 8 180.000,00 Suhl Schmiedefeld a. Rstg. Einzelprojekt Aktiv-u. Naturregion Schmalkalden- 8 Aussichtturm am Mittleren -

Trams Der Welt / Trams of the World 2020 Daten / Data © 2020 Peter Sohns Seite/Page 1 Algeria

www.blickpunktstrab.net – Trams der Welt / Trams of the World 2020 Daten / Data © 2020 Peter Sohns Seite/Page 1 Algeria … Alger (Algier) … Metro … 1435 mm Algeria … Alger (Algier) … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Algeria … Constantine … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Algeria … Oran … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Algeria … Ouragla … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Algeria … Sétif … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Algeria … Sidi Bel Abbès … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Buenos Aires, DF … Metro … 1435 mm Argentina … Buenos Aires, DF - Caballito … Heritage-Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Buenos Aires, DF - Lacroze (General Urquiza) … Interurban (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Buenos Aires, DF - Premetro E … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Buenos Aires, DF - Tren de la Costa … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Córdoba, Córdoba … Trolleybus … Argentina … Mar del Plata, BA … Heritage-Tram (Electric) … 900 mm Argentina … Mendoza, Mendoza … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Mendoza, Mendoza … Trolleybus … Argentina … Rosario, Santa Fé … Heritage-Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Rosario, Santa Fé … Trolleybus … Argentina … Valle Hermoso, Córdoba … Tram-Museum (Electric) … 600 mm Armenia … Yerevan … Metro … 1524 mm Armenia … Yerevan … Trolleybus … Australia … Adelaide, SA - Glenelg … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Australia … Ballarat, VIC … Heritage-Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Australia … Bendigo, VIC … Heritage-Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm www.blickpunktstrab.net – Trams der Welt / Trams of the World 2020 Daten / Data © 2020 Peter Sohns Seite/Page