Switzerland Welcomes Foreign Investment and Accords It National Treatment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aerodrome Chart 18 NOV 2010

2010-10-19-lsza ad 2.24.1-1-CH1903.ai 19.10.2010 09:18:35 18 NOV 2010 AIP SWITZERLAND LSZA AD 2.24.1 - 1 Aerodrome Chart 18 NOV 2010 WGS-84 ELEV ft 008° 55’ ARP 46° 00’ 13” N / 008° 54’ 37’’ E 915 01 45° 59’ 58” N / 008° 54’ 30’’ E 896 N THR 19 46° 00’ 30” N / 008° 54’ 45’’ E 915 RWY LGT ALS RTHL RTIL VASIS RTZL RCLL REDL YCZ RENL 10 ft AGL PAPI 4.17° (3 m) MEHT 7.50 m 01 - - 450 m PAPI 6.00° MEHT 15.85 m SALS LIH 360 m RLLS* SALS 19 PAPI 4.17° - 450 m 360 m MEHT 7.50 m LIH Turn pad Vedeggio *RLLS follows circling Charlie track RENL TWY LGT EDGE TWY L, M, and N RTHL 19 RTIL 10 ft AGL (3 m) YCZ 450 m PAPI 4.17° HLDG POINT Z Z ACFT PRKG LSZA AD 2.24.2-1 GRASS PRKG ZULU HLDG POINT N 92 ft AGL (28 m) HEL H 4 N PRKG H 3 H 83 ft AGL 2 H (25 m) 1 ASPH 1350 x 30 m Hangar L H MAINT AIRPORT BDRY 83 ft AGL Surface Hangar (25 m) L APRON BDRY Apron ASPH HLDG POINT L TWY ASPH / GRASS MET HLDG POINT M AIS TWR M For steep APCH PROC only C HLDG POINT A 40 ft AGL HLDG POINT S PAPI (12 m) 6° S 33 ft AGL (10 m) GP / DME PAPI YCZ 450 m 4.17° GRASS PRKG SIERRA 01 50 ft AGL 46° (15 m) 46° RTHL 00’ 00’ RTIL RENL Vedeggio CWY 60 x 150 m 1:7500 Public road 100 0 100 200 300 400 m COR: RWY LGT, ALS, AD BDRY, Layout 008° 55’ SKYGUIDE, CH-8602 WANGEN BEI DUBENDORF AMDT 012 2010 18 NOV 2010 LSZA AD 2.24.1 - 2 AIP SWITZERLAND 18 NOV 2010 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK AMDT 012 2010 SKYGUIDE, CH-8602 WANGEN BEI DUBENDORF 16 JUL 2009 AIP SWITZERLAND LSZA AD 2.24.10 - 1 16 JUL 2009 SKYGUIDE, CH-8602 WANGEN BEI DUBENDORF REISSUE 2009 16 JUL 2009 LSZA AD 2.24.10 - 2 -

Rapport De Gestion 2019/2020 7,9

2019 | 2020 | 2019 Rapport de gestion Geschäftsbericht | Rapport de gestion 2019 | 2020 Geschäftsbericht 2019 | 2020 | 2019 Sommaire 4 Avant-propos 5 Engagement politique 12 Service d'information 19 Événements 23 Prix LITRA 25 Organes de l'association 29 Secrétariat 33 Finances Avant-propos Berne, 26 | 07 | 2020 Après une année 2019 fructueuse pour les TP, nous venons tous de vivre des mois particuliers. La crise du coronavirus a eu un impact massif sur les transports publics. Au cours de sa session spéciale début mai 2020, le Parlement a été actif et a envoyé une motion demandant au Conseil fédéral, en collaboration avec les cantons et les entreprises de transport, de préparer un projet de loi sur la manière de compenser les pertes de recettes induites par le recul massif de la demande. Le Conseil fédéral a agi rapidement et il a élaboré une proposition sur la compensation des pertes de recettes estimées d'un volume de 800 millions de francs. La proposition a été soumise à consultation. Le secteur des TP fait face à des défis majeurs : nous devons à nouveau convaincre la population de prendre les transports en commun, rétablir la confiance, et prouver qu'ils ne représentent pas un risque, mais bien plutôt une partie de la solution d'une mobilité fiable, efficace et écologique. J'ai été très impressionné par la façon dont les membres de la LITRA et leurs collaborateurs ont géré la crise du coronavirus jusqu'à présent ainsi que par l'engagement exceptionnel dont ils ont fait preuve. Une fois de plus, les personnels ont démontré que les trains, les bus, les bateaux et les remontées mécaniques constituent la colonne vertébrale de notre société mobile. -

RUAG Ammotec Leading Ammunition Technology

RUAG Ammotec Leading Ammunition Technology RUAG Ammotec 1 One target, one round, one choice. RUAG Ammotec. RUAG Ammotec stands for a most sophisticated ammunition technology. Our professionals develop and manufacture high-performance, small-calibre standard and special ammunition for Hunting & Sports and Defence & Law Enforcement, as well as pyrotechnical elements and components for industry in general. On the basis of our value system which is based on high performance, visionary thinking and collaboration, our enterprise ensures that you can fully rely on RUAG Ammotec and its products in any situation. The mutual trust and satisfaction of our customers are the result of a precision job, high quality standards and last but not least a personal, honest relationship. More than 2,200 dedicated employees and 180 sales partners see to it that we are ready on the spot to satisfy your individual requirements. Together with you we work out solutions which meet future demands. We look forward with confidence, are flexible and ready to take new, even unusual approaches. You aim at a target and we offer you the right ammunition to reach it. In the interest of your success we hope to be your first choice. We want you to assess us against the fulfilment of this daily promise and intend to achieve success together with you, our customer, partner or fellow worker. Welcome to RUAG Ammotec. Christoph M. Eisenhardt CEO RUAG Ammotec RUAG Ammotec 3 Who we are About RUAG Ammotec Based upon a 150-year heritage of quality and innovation, RUAG Ammotec has become a trusted technology leader and strategic partner in the global ammunition industry. -

Annual Report 2009 on the Activity of the Swiss Federal Audit Office

EIDGENÖSSISCHE FINANZKONTROLLE CONTRÔLE FÉDÉRAL DES FINANCES CONTROLLO FEDERALE DELLE FINANZE SWISS FEDERAL AUDIT OFFICE Annual Report 2009 on the Activity of the Swiss Federal Audit Office Editorial The Swiss Federal Audit Office, a politically out its duties in a highly dedicated and profes - neutral specialist authority, is the supreme sional manner. The deficiencies listed in this financial supervisory body of the Confederation. report are not intended to call this opinion into Its aim is to advocate proper and lawful finan - question. I would like to take this opportunity to cial conduct by the Administration. In an age thank the Finance Delegation and the Federal of results-oriented public management, it is Council, which understand the role of the Swiss increasingly committed to improving the effective- Federal Audit Office as an independent, critical ness of government activity via comprehensive audit authority. I would also like to express my audits and analyses. The Swiss Federal Audit gratitude to the numerous employees in the Office seeks to locate deficiencies and weak - audited offices who readily supported the work nesses by taking a critical view, and not only to of the Swiss Federal Audit Office in the interests achieve temporary improvements but also to of the cause at hand. Finally, I would like to fundamentally optimize government actions thank the employees of the Swiss Federal Audit thanks to professional advocacy. Consequently, Office, who go about their demanding work with the Swiss Federal Audit Office focuses on dedication and motivation in the interests of dialogue with those audited in order to ensure taxpayers. its recommendations are willingly accepted. -

RUAG Completes Acquisition of Cyber Security Company Clearswift

Page 1 / 2 Media release RUAG completes acquisition of cyber security company Clearswift Bern (Switzerland), Theale (UK), 23 January 2017. RUAG Defence has successfully completed the acquisition of the British cyber security company Clearswift announced in December 2016. This acquisition enables RUAG to enhance key aspects of its current product and service portfolio in the area of cyber security. The acquisition of Clearswift increases the number of employees at RUAG’s new Cyber Security business unit, established at the beginning of 2017, to over 230 cyber security experts at locations in Switzerland, the UK, Germany, the USA, Australia and Japan. Clearswift is a global cyber security company with a product portfolio in the areas of data loss prevention and deep content inspection, with more than 2,300 customers in over 70 countries. In 2016 it generated sales exceeding GBP 23 million. “Clearswift’s products for the protection of critical data are the perfect complement to RUAG’s network expertise. Clearswift also has a strong research and development department, a global service organisation and established international sales channels”, says Urs Breitmeier, CEO of RUAG. In turn, the merger provides Clearswift with access to RUAG’s customer base, local and national authorities, the military and operators of critical infrastructures. “With the new Cyber Security business unit we want to position ourselves as a provider of high-quality specialist solutions and services for the customers worldwide in various sectors”, Urs Breitmeier adds. The headquarters of the Cyber Security business unit are in Switzerland. The UK site will be the centre of excellence for software business in the combined cyber security business, and the “Clearswift” brand will be retained. -

Annual Report 2018 Eidgenössische Finanzkontrolle Contrôle Fédéral Des Finances Controllo Federale Delle Finanze Swiss Federal Audit Office

EIDGENÖSSISCHE FINANZKONTROLLE CONTRÔLE FÉDÉRAL DES FINANCES CONTROLLO FEDERALE DELLE FINANZE SWISS FEDERAL AUDIT OFFICE 2018 ANNUAL REPORT BERN | MAY 2019 SWISS FEDERAL AUDIT OFFICE Monbijoustrasse 45 3003 Bern – Switzerland T. +41 58 463 11 11 F. +41 58 453 11 00 [email protected] twitter @EFK_CDF_SFAO WWW.SFAO.ADMIN.CH DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD FROM WHISTLEBLOWING TO PARTICIPATORY AUDITING In 2008, federal employees were not form www.whistleblowing.admin.ch. It is legally required to report the felonies now the IT system that ensures the an- they encountered to the courts. The onymous processing of reports. These experts of GRECO, a Council of Europe reports come from federal employees, anti-corruption body, pointed out this but also from third parties who have wit- shortcoming at that time in their evalu- nessed irregularities. ation report on Switzerland. For the SFAO, processing this infor- To remedy this shortcoming, the Federal mation is not simple. It is necessary to Office of Justice, in close cooperation sift through the information and critic- with the Federal Office of Personnel and ally verify onsite whether it is plausible. the Swiss Federal Audit Office (SFAO), Some reports may actually be intended introduced on 1 January 2011 the new to harm someone. It is then necessary Article 22a of the Federal Personnel to identify the appropriate time to initiate Act and the obligation to report felonies possible criminal proceedings and avoid and misdemeanours prosecuted ex of- obstructing them by alerting the perpe- ficio. This is when whistleblowing was trators of an offence. In any case, noth- launched at the federal administrative ing that could put the whistleblower in level. -

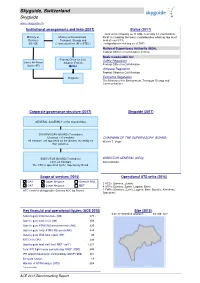

Skyguide, Switzerland Skyguide Institutional Arrangements and Links (2017) Status (2017) - Joint-Stock Company As of 1996

Skyguide, Switzerland Skyguide www.skyguide.ch Institutional arrangements and links (2017) Status (2017) - Joint-stock company as of 1996. Currently 14 shareholders; Ministry of Ministry of Environment, 99,91% is held by the Swiss Confederation which by law must Defence Transport, Energy and hold at least 51% (M of D) Communications (M of ETEC) - Integrated civil/military as of 2001 National Supervisory Authority (NSA): Federal Office for Civil Aviation (FOCA) Body responsible for: Federal Office for Civil Safety Regulation Swiss Air Force Aviation (FOCA) Federal Office for Civil Aviation (Swiss AF) [NSA Airspace Regulation Federal Office for Civil Aviation Skyguide Economic Regulation The Ministry of the Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications Corporate governance structure (2017) Skyguide (2017) GENERAL ASSEMBLY of the Shareholders SUPERVISORY BOARD (7 members) Chairman + 6 members CHAIRMAN OF THE SUPERVISORY BOARD: All members are appointed by the General Assembly for Walter T. Vogel their expertise. EXECUTIVE BOARD (7 members) DIRECTOR GENERAL (CEO): CEO + 6 members Daniel Weder The CEO is appointed by the Supervisory Board. Scope of services (2015) Operational ATS units (2015) GAT Upper Airspace Oceanic ANS 2 ACCs (Geneva, Zurich) OAT Lower Airspace MET 4 APPs (Geneva, Zurich, Lugano, Bern) - ATC services delegated to Geneva ACC by France 7 TWRs (Geneva, Zurich, Lugano, Bern, Buochs, Altenrhein, Grenchen) Key financial and operational figures (ACE 2015) Size (2015) Size of controlled airspace:69 700 km² Gate-to-gate total revenues (M€) 377 Gate-to-gate total costs (M€) 356 Gate-to-gate ATM/CNS provision costs (M€) 330 Gate-to-gate total ATM/CNS assets(M€) 338 Gate-to-gate ANS total capex (M€) 48 ATCOs in OPS 348 Gate-to-gate total staff (incl. -

Download Presentations

Your hosts Lukas Sieber Matt Julian Executive Director North America Director US Greater Zurich Area Ltd (GZA) Greater Geneva Bern area (GGBa) [email protected] [email protected] 2 Greater Zurich Area & Greater Geneva Bern area GreaterGreater Zurich Zurich Area Area Ltd (GZA) (GZA) & Greater – a public Geneva-private Bern partnership area (GGBa) Your Swiss business concierges Site selection & site visits Connect & integrate Advice & support 3 Greater Zurich Area Webinar Housekeeping All webinar recordings available on: greaterzuricharea.com/webinars ggba-switzerland.ch/en/webinars 4 Greater Zurich Area & Greater Geneva Bern area “The Silicon Valley of Robotics & Autonomous Systems” Global #: influential research and development …world leading institutes & initiatives Disruptive Companies Biggest Swiss Hubs! Sources: Web of Science Thomson Reuters, 2018; CB Insights; 5 Greater Zurich Area & Greater Geneva Bern area Gottlieb Duttweiler Institute, GDI, investiere.ch ranking 2018, EIGE 2018 Andrea Marrazzo Head of Autonomous Delivery & IoT & Blockchain at Swiss Post B.Sc. in Business Informatics at HF Business Informatics Switzerland [email protected] 6 Greater Zurich Area & Greater Geneva Bern area SWISS POST VIRTUALTechnische Angaben SWISS DRONE INDUSTRY TOUR Bildgrösse: Vollflächig Bilder einfügen: 14.12.2020B 33,87 cm x H 19,05 cm entsprechen «Post-Menü > Bild» ANDREAB 2000 Pixel x H 1125 MARRAZZOPixel Weitere Bilder unter Auflösung 150 dpi www.brandingnet.ch TODAY OPERATIONS If you can read this text, -

Security & Defence European

a 7.90 D 14974 E D European & Security ES & Defence 10/2019 International Security and Defence Journal ISSN 1617-7983 • US Army Priorities • The US and NATO • European Combat Helicopter Acquisition • EU Defence Cooperation • Surface-to-Air Missile Developments www.euro-sd.com • • New Risks of Digitised Wars • Italy's Fleet Renewal Programme • Light Tactical Vehicles • UGVs for Combat Support • Defence Procurement in Denmark • Taiwan's Defence Market • Manned-Unmanned Teaming • European Mortar Industry October 2019 Politics · Armed Forces · Procurement · Technology LIFETIME EXCELLENCE At MTU Aero Engines, we always have your goals in mind. As a reliable partner for military engines, our expertise covers the entire engine lifecycle. And our tailored services guarantee the success of your missions. All systems go! www.mtu.de Militaer_E_210x297_European_Security_Defence_20191001_01.indd 1 17.09.19 08:06 Editorial Juncker’s Heritage The end of October marks the conclusion of the term of office of Jean-Claude Juncker as President of the European Commission. His legacy to his successor Ursula von der Leyen is largely a heap of dust and ashes. Five years ago he came to power with a fanfare for the future. The European Union was to be given a new burst of vitality, become closer to its citizens, at last put an end to its constant preoccupation with itself, and work towards solving the real problems of our times. None of these good intentions have been transformed into reality, not even notionally. Instead, the situation has become worse – a whole lot worse. This is due not least to the fact that the United Kingdom is on the verge of leaving the Euro- pean Union. -

Annual Report 2018 «Exemplary in Energy

Exemplary in energy An initiative of the Confederation Annual report 2018 Federal Department of the Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications DETEC Swiss Federal Office of Energy SFOE Office Exemplary in energy EE Publishing information Publisher Office Exemplary in energy EE Swiss Federal Office of Energy SFOE, 3003 Bern www.energie-vorbild.ch Project management for this report Claudio Menn, Swiss Federal Office of Energy SFOE, Office Exemplary in energy EE Members of the Exemplary in energy Coordination Group CG-EEI Alexandre Bagnoud, Services Industriels de Genève (SIG) Daniel Büchel, Swiss Federal Office of Energy SFOE Pierre-Yves Diserens, Genève Aéroport Désirée Föry, Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport DDPS Hubert Lieb, Suva Carmen Maybud, Civil Federal Administration Christina Meier, Swiss Federal Railways Stefan Meyer, Skyguide Giancarlo Serafin, ETH Board Res Witschi, Swisscom Anne Wolf, Swiss Post Office Exemplary in energy EE Claudio Menn, Swiss Federal Office of Energy SFOE Technical consultants to the EEI Office Cornelia Brandes and Charlotte Spörndli, Brandes Energie AG, Zurich Thomas Weisskopf and Stefanie Steiner, Weisskopf Partner GmbH, Zurich Concept Weissgrund AG, Zurich Design and texts Polarstern GmbH, Lucerne and Solothurn Distribution www.bundespublikationen.admin.ch Article number 805.075.18.ENG 06.2019 50ENG 860443925 Bern, June 2019 energy neutral 2 Contents Editorial 5 Giving a clear signal 6 The 10 actors 8 Focus: Re-use of used IT equipment 14 Meaningfully re-using used hardware -

Downloadables/FACTS FIGURES 05 E.PDF

- 46 - REFERENCES Da Costa, Mercedes and V. Hugo Juan-Ramon, 2006: “The New Worth Approach to Fiscal Analysis: Dynamics and Rules”, IMF Working Paper/06/17. Kamps, Christophe, 2004: “New Estimates of Government Net Capital Stocks for 22 OECD Countries 1960–2001” IMF Working Paper No. 67, Washington, D.C. International Monetary Fund, 2005a: “Intertemporal Policy Consistency in Switzerland: Is the Current Social Insurance Sustainable?”, chapter I in “Switzerland: Selected Issues”, IMF Country Report no. 05/188, p. 3–39. ________, 2005b: “The Need for Health Care Reform”, chapter II in “Switzerland: Selected Issues”, IMF Country Report no. 05/188, p. 40-47. ________, 2005c: “Switzerland: 2005 Article IV Consultation – Staff Report”, IMF Country Report no. 05/190. ________, 2005d: “Using the GFSM Statistical Framework to Strengthen Fiscal Analysis in the Fund”, www.imf.org. ________, 2006a: “A Preliminary Public Sector Balance Sheet for Germany”, chapter III in “Germany: Selected Issues”, IMF Country Report no. 06/17, p. 35–44. ________, 2006b: “Germany: 2005 Article IV Consultation – Staff Report”, IMF Country Report no. 06/17. Swiss National Bank, 2005a: “Swiss Financial Accounts. Stocks of financial assets and liabilities 1999-2003”. ________, 2005b: “Banks in Switzerland”. ________, 2004: “Annual Report”. Ruag: http://www.ruag.com/ruag/binary?media=118138&open=true SBB: 2005 balance sheet: http://212.254.205.12/geschaeftsbericht/pdf/F_Bilanz_e.pdf Skyguide: http://www.skyguide.ch/en/MediaRelations/Publications/downloadables/FACTS_FIGURES _05_E.PDF Swiss medic: http://www.swissmedic.ch/files/pdf/swissmedic_GB_2004.pdf ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution - 47 - III. A COMPARISON OF THE SWISS, DUTCH, AND U.K. -

Annual Report 2019

Annual report 2019 Federal Department of the Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications DETEC Swiss Federal Office of Energy SFOE Office Exemplary Energy and Climate EEC Publishing information Publisher Office Exemplary Energy and Climate EEC Swiss Federal Office of Energy SFOE, 3003 Bern www.exemplary-energy-climate.ch Project management for this report Claudio Menn, Swiss Federal Office of Energy SFOE, Office Exemplary Energy and Climate EEC Members of the Exemplary Energy and Climate Coordination Group CG-EEC Alexandre Bagnoud, SIG Daniel Büchel, Swiss Federal Office of Energy SFOE Pierre-Yves Diserens, Genève Aéroport Andrea Riedel, Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport DDPS Hubert Lieb, Suva Carmen Maybud, Civil Federal Administration Christina Meier, SBB Stefan Meyer, Skyguide Giancarlo Serafin, ETH Board Res Witschi, Swisscom Anne Wolf, Swiss Post Office Exemplary Energy and Climate EEC Claudio Menn, Swiss Federal Office of Energy SFOE Technical consultants to the EEC Office Cornelia Brandes and Charlotte Spörndli, Brandes Energie AG, Zurich Thomas Weisskopf, Stefanie Steiner and Daniel Arnet, Weisskopf Partner GmbH, Zurich Concept Weissgrund AG, Zurich Design and texts Polarstern AG, Lucerne and Solothurn Distribution www.bundespublikationen.admin.ch Article number 805.075.19ENG 06.2020 200ENG 862680478 Bern, June 2020 HQHUJ\QHXWUDO 2 Contents Editorial 5 Giving a clear signal 6 The 10 actors 8 Continuation and re-orientation of the initiative 13 Focus: renewable energies and waste heat recovery 14 Producing