Max Kowalski's <I>Japanischer Frühling</I>: a Song Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gluck 300 Years

Christoph Willibald GLUCK 300 YEARS ALCESTE Livemitschnitt aus der Staatsoper Stuttgart, 2006 Catherine Naglestad, Donald Kaasch, Johan Rydh, Catriona Smith, Michael Ebbecke Chor und Orchester der Staatsoper Stuttgart Musikalische Leitung Constantinos Carydis Regie Jossi Wieler, Sergio Morabito IPHIGÉNIE EN TAURIDE Livemitschnitt aus dem Opernhaus Zürich, 2001 Rodney Gilfry, Juliette Galstian, Deon van der Walt Orchester “La Scintilla” des Opernhaus Zürich Musikalische Leitung William Christie Regie Claus Guth ORFEO ED EURIDICE Livemitschnitt aus dem Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 1991 Jochen Kowalski, Gillian Webster, Jeremy Budd 8 07280 81119 3 Chor und Orchester des Royal Opera House Untertitel: GB, DE, FR, ES, IT Musikalische Leitung Hartmut Haenchen Katalognummer: 108 111 Regie Harry Kupfer Laufzeit: 83 min (Orfeo ed Euridice) | 165 min (Alceste) 108 min (Iphigénie en Tauride) | 60 min Bonus Anlässlich des 300. Geburtstages von Christoph Tonformat: PCM Stereo Willibald Gluck am 02. Juli 2014 Bildformat: 4:3 (Orfeo ed Euridice) 16:9 (Alceste, Iphigénie en Tauride), 1080i Full HD Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787) gilt als der Reformator der Format: 50 GB Dual Layer Oper des 18. Jahrhunderts und übte einen großen Einfl uss auf die FSK: 0 Entwicklung des Musiktheaters seiner Zeit aus. Zu Ehren seines 300. VÖ: 07.07.2014 Geburtstags veröffentlicht Arthaus Musik nun eine Sonderedition mit drei preisgekrönten Inszenierungen Glucks größter Opernkompositionen auf einer Blu-ray Disc: Jossi Wieler und Sergio Morabitos „Alceste“ aus Stuttgart („Aufführung des Jahres 2006“, Opernwelt), „Iphigénie en Tauride“ aus Zürich (2001) unter der musikalischen Leitung des Barockspezialisten William Christie und Harry Kupfers legendäre Inszenierung von „Orfeo ed Euridice“ aus dem Royal Opera House mit Jochen Kowalski als Titelheld (Olivier Award). -

Zum Download Des Heftes Bitte Anklicken

DREIGROSCHENHEFT INFORMATIONEN ZU BERTOLT BRECHT 24. JAHRGANG HEFT 3/2017 COLLAGEN-AUSSTELLUNG IM AUGSBURGER BRECHTHAUS (FOTO) A. DÜMLING: VON WEM STAMMT DIE SEERÄUBER-JENNY? D. HENNING ÜBER BRECHTS SATZ ZU SIDNEY HOOK WER WAR DER HAUSARZT DER FAMILIE BRECHT? brechtige Bildbände aus dem Wißner-Verlag Seiten | über farbige Abbildungen ISBN ---- | , Seiten | über farbige Abbildungen ISBN ---- | , Mehr tolle Bildbände, spannende Erzählungen und weitere schöne Seiten von Augsburg nden Sie beim Wißner-Verlag unter www.wissner.com Bücher erhältlich im Buchhandel oder direkt beim Verlag. Anzeige_3GH_Jugendstil-Historismus_170228.indd 1 01.03.2017 15:06:08 INHALT Editorial 2 STALIN Impressum 2 Brecht und der Stalinismus 29 Ein Kommentar-Leserbrief zu den Brecht-Tagen KUNST 2017 „‚Ich bereite meinen nächsten Irrtum vor…‘ – Brecht und die Sowjetunion“ Köppelsbleek: Eine überraschende Florian Vaßen Verbindungslinie von Ernst Jünger zu Sidney Hook reicht Brecht Hut und Mantel 31 Caspar Neher und Bert Brecht 3 „Je unschuldiger sie sind, desto mehr verdienen Michael Friedrichs sie zu sterben “ Brecht-Arbeiten von Hanfried Wendland 6 Dieter Henning Volkmar Häußler FILM THEATER Die Brecht-Filme von Peter Voigt 40 Liegen die Wurzeln von Bert Brechts Epischem Erdmut Wizisla Theater im Mittelalter? 9 Klaus Wolf HEGEL „Die Kleinbürgerhochzeit“ in Wies/ Minima Hegeliana Zu Brechts Denkbildern (7) Weststeiermark 12 Die Ochsen des Pythagoras 42 Ernst Scherzer Frank Wagner Unibühne in Colorado zeigt „Arturo Ui“ 30 DER AUGSBURGER MUSIK Wer war der Hausarzt -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Richard Strauss Und Das Musikalische Urheberrecht 1933 / 1934

Richard Strauss – Der Komponist und sein Werk MÜNCHNER VERÖFFENTLICHUNGEN ZUR MUSIKGESCHICHTE Begründet von Thrasybulos G. Georgiades Fortgeführt von Theodor Göllner Herausgegeben seit 2006 von Hartmut Schick Band 77 Richard Strauss Der Komponist und sein Werk Überlieferung, Interpretation, Rezeption Bericht über das internationale Symposium zum 150. Geburtstag München, 26.–28. Juni 2014 Richard Strauss Der Komponist und sein Werk Überlieferung, Interpretation, Rezeption Bericht über das internationale Symposium zum 150. Geburtstag München, 26.–28. Juni 2014 Herausgegeben von Sebastian Bolz, Adrian Kech und Hartmut Schick Weitere Informationen über den Verlag und sein Programm unter: www.allitera.de Juni 2017 Allitera Verlag Ein Verlag der Buch&media GmbH, München © 2017 Buch&media GmbH, München © 2017 der Einzelbeiträge bei den AutorInnen Satz und Layout: Johanna Conrad, Augsburg Printed in Germany · ISBN 978-3-86906-990-6 Inhalt Vorwort . 9 Abkürzungsverzeichnis ............................................. 13 Richard Strauss in seiner Zeit Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen Des Meisters Lehrjahre. Der junge Richard Strauss und seine Meininger Ausbildungszeit bei Hans von Bülow ................................................ 17 Dietmar Schenk Berlins »Richard-Strauss-Epoche«. Richard Strauss und das Musikleben im kaiserlichen Berlin .............. 37 Dörte Schmidt Meister – Freunde – Zeitgenossen. Richard Strauss und Gerhart Hauptmann ............................. 51 Albrecht Dümling »… dass die Statuten der Stagma dringend zeitgemässer Revision -

Pierrot Lunaire Translation

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) Pierrot Lunaire, Op.21 (1912) Poems in French by Albert Giraud (1860–1929) German text by Otto Erich Hartleben (1864-1905) English translation of the French by Brian Cohen Mondestrunken Ivresse de Lune Moondrunk Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt, Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux The wine we drink with our eyes Gießt Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder, A flots verts de la Lune coule, Flows nightly from the Moon in torrents, Und eine Springflut überschwemmt Et submerge comme une houle And as the tide overflows Den stillen Horizont. Les horizons silencieux. The quiet distant land. Gelüste schauerlich und süß, De doux conseils pernicieux In sweet and terrible words Durchschwimmen ohne Zahl die Fluten! Dans le philtre yagent en foule: This potent liquor floods: Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt, Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux The wine we drink with our eyes Gießt Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder. A flots verts de la Lune coule. Flows from the moon in raw torrents. Der Dichter, den die Andacht treibt, Le Poète religieux The poet, ecstatic, Berauscht sich an dem heilgen Tranke, De l'étrange absinthe se soûle, Reeling from this strange drink, Gen Himmel wendet er verzückt Aspirant, - jusqu'à ce qu'il roule, Lifts up his entranced, Das Haupt und taumelnd saugt und schlürit er Le geste fou, la tête aux cieux,— Head to the sky, and drains,— Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt. Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux! The wine we drink with our eyes! Columbine A Colombine Colombine Des Mondlichts bleiche Bluten, Les fleurs -

Toccata Classics TOCC0147 Notes

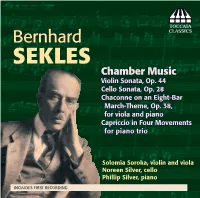

TOCCATA Bernhard CLASSICS SEKLES Chamber Music Violin Sonata, Op. 44 Cello Sonata, Op. 28 Chaconne on an Eight-Bar March-Theme, Op. 38, for viola and piano ℗ Capriccio in Four Movements for piano trio Solomia Soroka, violin and viola Noreen Silver, cello Phillip Silver, piano INCLUDES FIRST RECORDING REDISCOVERING BERNHARD SEKLES by Phillip Silver he present-day obscurity of Bernhard Sekles illustrates how porous is contemporary knowledge of twentieth-century music: during his lifetime Sekles was prominent as teacher, administrator and composer alike. History has accorded him footnote status in two of these areas of endeavour: as an educator with an enviable list of students, and as the Director of the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt from 923 to 933. During that period he established an opera school, much expanded the area of early-childhood music-education and, most notoriously, in 928 established the world’s irst academic class in jazz studies, a decision which unleashed a storm of controversy and protest from nationalist and fascist quarters. But Sekles was also a composer, a very good one whose music is imbued with a considerable dose of the unexpected; it is traditional without being derivative. He had the unenviable position of spending the prime of his life in a nation irst rent by war and then enmeshed in a grotesque and ultimately suicidal battle between the warring political ideologies that paved the way for the Nazi take-over of 933. he banning of his music by the Nazis and its subsequent inability to re-establish itself in the repertoire has obscured the fact that, dating back to at least 99, the integration of jazz elements in his works marks him as one of the irst European composers to use this emerging art-form within a formal classical structure. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XVIII, Number 1 April 2003 A PILGRIMAGE TO IOWA As I sat in the United Airways terminal of O’Hare International Airport, waiting for the recently bankrupt carrier to locate and then install an electric starter for the no. 2 engine, my mind kept returning to David Lodge’s description of the modern academic conference. In Small World (required airport reading for any twenty-first century academic), Lodge writes: “The modern conference resembles the pilgrimage of medieval Christendom in that it allows the participants to indulge themselves in all the pleasures and diversions of travel while appearing to be austerely bent on self-improvement.” He continues by listing the “penitential exercises” which normally accompany the enterprise, though, oddly enough, he omits airport delays. To be sure, the companionship in the terminal (which included nearly a dozen conferees) was anything but penitential, still, I could not help wondering if the delay was prophecy or merely a glitch. The Maryland Handel Festival was a tough act to follow and I, and perhaps others, were apprehensive about whether Handel in Iowa would live up to the high standards set by its august predecessor. In one way the comparison is inappropriate. By the time I started attending the Maryland conference (in the early ‘90’s), it was a first-rate operation, a Cadillac among festivals. Comparing a one-year event with a two-decade institution is unfair, though I am sure in the minds of many it was inevitable. Fortunately, I feel that the experience in Iowa compared very favorably with what many of us had grown accustomed Frontispiece from William Coxe, Anecdotes fo George Frederick Handel and John Christopher Smith to in Maryland. -

The Mahabharata Epic, Its Translations and Its Influence on Polish Intellectual Circles and General Readers

Iuvenilia Philologorum Cracoviensium, t. V Źródła Humanistyki Europejskiej 5 Kraków 2012, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego ISBN 978-83-233-3465-1, ISSN 2080-5802 IWONA MILEWSKA Instytut Orientalistyki UJ The Mahabharata Epic, Its Translations and Its Influence on Polish Intellectual Circles and General Readers The Mahabharata, one of the two most famous Indian or, to be more precise, Sanskrit epics, is up till modern days not fully known to Polish intellectuals nor to general readers. It is, among other reasons, due to the lack of its comprehen- sive translation into Polish. Even if the general information about Sanskrit literature, and in particular about the epics, or the Mahabharata, was circulating throughout Europe since the turn of 18th and 19th centuries, its way to Poland was a long one. Nowadays in Poland it is obviously easier to find competent information on India and its literature but still in most cases the detailed descriptions of the Ma- habharata epic are included in books directed to specialists rather than to gen- eral readers not to mention fragments of its direct translations into Polish which are till now extremely rare. It is known that the Europeans became deeply interested in India when the British started to be present there. They were the first to raise the interest in their literature. In this context such names as William Jones, Charles Wilkins or Henry Thomas Colebrooke should be mentioned. Their works, mostly of linguistics character, started to circulate in Europe at the turn of 18 and 19th centuries. In France one of the first scholars who focused also on India was A. -

Anthology of Polish Poetry. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad Program, 1998 (Hungary/Poland)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 444 900 SO 031 309 AUTHOR Smith, Thomas A. TITLE Anthology of Polish Poetry. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad Program, 1998 (Hungary/Poland). INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 206p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020)-- Guides Classroom - Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Anthologies; Cultural Context; *Cultural Enrichment; *Curriculum Development; Foreign Countries; High Schools; *Poetry; *Poets; Polish Americans; *Polish Literature; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Poland; Polish People ABSTRACT This anthology, of more than 225 short poems by Polish authors, was created to be used in world literature classes in a high school with many first-generation Polish students. The following poets are represented in the anthology: Jan Kochanowski; Franciszek Dionizy Kniaznin; Elzbieta Druzbacka; Antoni Malczewski; Adam Mickiewicz; Juliusz Slowacki; Cyprian Norwid; Wladyslaw Syrokomla; Maria Konopnicka; Jan Kasprowicz; Antoni Lange; Leopold Staff; Boleslaw Lesmian; Julian Tuwim; Jaroslaw Iwaszkiewicz; Maria Pawlikowska; Kazimiera Illakowicz; Antoni Slonimski; Jan Lechon; Konstanty Ildefons Galczynski; Kazimierz Wierzynski; Aleksander Wat; Mieczyslaw Jastrun; Tymoteusz Karpowicz; Zbigniew Herbert; Bogdan Czaykowski; Stanislaw Baranczak; Anna Swirszczynska; Jerzy Ficowski; Janos Pilinsky; Adam Wazyk; Jan Twardowski; Anna Kamienska; Artur Miedzyrzecki; Wiktor Woroszlyski; Urszula Koziol; Ernest Bryll; Leszek A. Moczulski; Julian Kornhauser; Bronislaw Maj; Adam Zagajewskii Ferdous Shahbaz-Adel; Tadeusz Rozewicz; Ewa Lipska; Aleksander Jurewicz; Jan Polkowski; Ryszard Grzyb; Zbigniew Machej; Krzysztof Koehler; Jacek Podsiadlo; Marzena Broda; Czeslaw Milosz; and Wislawa Szymborska. (BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. Anthology of Polish Poetry. Fulbright Hays Summer Seminar Abroad Program 1998 (Hungary/Poland) Smith, Thomas A. -

Trude Hesterberg She Opened Her Own Cabaret, the Wilde Bühne, in 1921

Hesterberg, Trude Trude Hesterberg she opened her own cabaret, the Wilde Bühne, in 1921. She was also involved in a number of film productions in * 2 May 1892 in Berlin, Deutschland Berlin. She performed in longer guest engagements in Co- † 31 August 1967 in München, Deutschland logne (Metropol-Theater 1913), alongside Massary at the Künstlertheater in Munich and in Switzerland in 1923. Actress, cabaret director, soubrette, diseuse, operetta After the Second World War she worked in Munich as singer, chanson singer theater and film actress, including as Mrs. Peachum in the production of The Threepenny Opera in the Munich „Kleinkunst ist subtile Miniaturarbeit. Da wirkt entwe- chamber plays. der alles oder nichts. Und dennoch ist sie die unberechen- Biography barste und schwerste aller Künste. Die genaue Wirkung eines Chansons ist nicht und unter gar keinen Umstän- Trude Hesterberg was born on 2 May, 1892 in Berlin den vorauszusagen, sie hängt ganz und gar vom Publi- “way out in the sticks” in Oranienburg (Hesterberg. p. 5). kum ab.“ (Hesterberg. Was ich noch sagen wollte…, S. That same year, two events occurred in Berlin that would 113) prove of decisive significance for the life of Getrude Joh- anna Dorothea Helen Hesterberg, as she was christened. „Cabaret is subtle work in miniature. Either everything Firstly, on on 20 August, Max Skladonowsky filmed his works or nothing does. And it is nonetheless the most un- brother Emil doing gymnastics on the roof of Schönhau- predictable and difficult of the arts. The precise effect of ser Allee 148 using a Bioscop camera, his first film record- a chanson is not foreseeable under any circumstances; it ing. -

Narrative Structure and Purpose in Arnold Schoenberg's Pierrot

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Clown: Narrative Structure and Purpose in Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire Mike Fabio Introduction In September of 1912, a 37-year-old Arnold Schoenberg sat in a Berlin concert hall awaiting the premier of his 21st opus, Pierrot Lunaire. A frail man, as rash in his temperament as he was docile when listening to his music, Schoenberg watched as the lights dimmed and a fully costumed Pierrot took to the stage, a spotlight illuminating him against a semitransparent black screen through which a small instrumental ensemble could be seen. But as Pierrot began singing, the audience quickly grew uneasy, noting that Pierrot was in fact a woman singing in the most awkward of styles against a backdrop of pointillist atonal brilliance. Certainly this was not Beethoven. In a review of the concert, music critic James Huneker wrote: The very ecstasy of the hideous!…Schoenberg is…the cruelest of all composers, for he mingles with his music sharp daggers at white heat, with which he pares away tiny slices of his victim’s flesh. Anon he twists the knife in the fresh wound and you receive another thrill…. There is no melodic or harmonic line, only a series of points, dots, dashes or phrases that sob and scream, despair, explode, exalt and blaspheme.1 Schoenberg was no stranger to criticism of this nature. He had grown increasingly contemptuous of critics, many of whom dismissed his music outright, even in his early years. When Schoenberg entered his atonal period after 1908, the criticism became far more outrageous, and audiences were noted to have rioted and left the theater in the middle of pieces.