Collectanea Medica, Consisting of Anecdotes, Facts, Extracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Group

Historical Group NEWSLETTER and SUMMARY OF PAPERS No. 61 Winter 2012 Registered Charity No. 207890 COMMITTEE Chairman: Prof A T Dronsfield, School of Education, | Prof J Betteridge (Twickenham, Middlesex) Health and Sciences, University of Derby, | Dr N G Coley (Open University) Derby, DE22 1GB [e-mail [email protected]] | Dr C J Cooksey (Watford, Hertfordshire) Secretary: | Prof E Homburg (University of Maastricht) Prof W P Griffith, Department of Chemistry, | Prof F James (Royal Institution) Imperial College, South Kensington, London, | Dr D Leaback (Biolink Technology) SW7 2AZ [e-mail [email protected]] | Dr P J T Morris (Science Museum) Treasurer; Membership Secretary: | Prof. J. W. Nicholson (University of Greenwich) Dr J A Hudson, Graythwaite, Loweswater, | Mr P N Reed (Steensbridge, Herefordshire) Cockermouth, Cumbria, CA13 0SU | Dr V Quirke (Oxford Brookes University) [e-mail [email protected]] | Dr S Robinson (Ham, Surrey) Newsletter Editor: | Prof. H. Rzepa (Imperial College) Dr A Simmons, Epsom Lodge, | Dr. A Sella (University College) La Grande Route de St Jean,St John, Jersey, JE3 4FL [e-mail [email protected]] Newsletter Production: Dr G P Moss, School of Biological and Chemical, Sciences Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS [e-mail [email protected]] http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/rschg/ http://www.rsc.org/membership/networking/interestgroups/historical/index.asp Contents From the Editor 2 RSC Historical Group News - Bill Griffith 3 Identification Query - W. H. Brock 4 Members’ Publications 5 NEWS AND UPDATES 6 USEFUL WEBSITES AND ADDRESSES 7 SHORT ESSAYS 9 The Copperas Works at Tankerton - Chris Cooksey 9 Mauveine - the final word? (3) - Chris Cooksey and H. -

Vol 57 Issue 2 April 2013

Published by Johnson Matthey Plc A quarterly journal of research on the science and technology of the platinum group metals and developments in their application in industry Vol 57 Issue 2 April 2013 www.platinummetalsreview.com E-ISSN 1471-0676 © Copyright 2013 Johnson Matthey http://www.platinummetalsreview.com/ Platinum Metals Review is published by Johnson Matthey Plc, refi ner and fabricator of the precious metals and sole marketing agent for the six platinum group metals produced by Anglo American Platinum Ltd, South Africa. All rights are reserved. Material from this publication may be reproduced for personal use only but may not be offered for re-sale or incorporated into, reproduced on, or stored in any website, electronic retrieval system, or in any other publication, whether in hard copy or electronic form, without the prior written permission of Johnson Matthey. Any such copy shall retain all copyrights and other proprietary notices, and any disclaimer contained thereon, and must acknowledge Platinum Metals Review and Johnson Matthey as the source. No warranties, representations or undertakings of any kind are made in relation to any of the content of this publication including the accuracy, quality or fi tness for any purpose by any person or organisation. E-ISSN 1471-0676 • Platinum Metals Rev., 2013, 57, (2), 85• Platinum Metals Review A quarterly journal of research on the platinum group metals and developments in their application in industry http://www.platinummetalsreview.com/ APRIL 2013 VOL. 57 NO. 2 Contents Johnson Matthey and Alfa Aesar Support Academic Research 86 An editorial by Sara Coles Platinum-Based and Platinum-Doped Layered Superconducting Materials: 87 Synthesis, Properties and Simulation By Alexander L. -

Alexander Marcet (1770-1822), Physician and Animal Chemist

ALEXANDER MARCET (1770-1822), PHYSICIAN AND ANIMAL CHEMIST by N. G. COLEY ALEXANDER John Gaspard Marcet1 was born in Geneva in the year 1770. His father, who was a merchant of Huguenot descent,2 wished him to follow the family business, but the young Alexander had no liking for commerce. Instead he decided to train for a career in the law, but before he could complete his studies he became involved in the disturbed political situation which arose in Geneva after the French Revolution.3 This resulted in his imprisonment, along with his boyhood friend Charles Gaspard de la Rive.4After the death of Robespierre in 1794 the two friends were at length successful in obtaining a special dispensation by which they were released from prison but were banished from Switzerland for five years. They then came to Edinburgh, where they took up the study of medicine, both gaining the M.D. on the same day in 1797. There was a strong chemical tradition in the University of Edinburgh at this time, deriving from the earlier influence of men like William Cullen. Joseph Black was in the chair of medicine and chemistry and the university was also served by Daniel Rutherford, from whom Marcet received instruction. The interest which Marcet was later to show in chemistry became apparent in that he chose to write his doctoral thesis on diabetes,5 about which several plausible chemical theories were currently under discussion in the university. Immediately after qualifying in 1797, Marcet moved to London where he was first of all assistant physician to the Public Dispensary in Cary Street. -

The Partnership of Smithson Tennant and William Hyde Wollaston

“A History of Platinum and its Allied Metals”, by Donald McDonald and Leslie B. Hunt 9 The Partnership of Smithson Tennant and William Hyde Wollaston “A quantity of platina was purchased by me a few years since with the design of rendering it malleable for the different purposes to which it is adapted. That object has now been attained. ” WILLIAM HYDE W O L L A S T O N Up to the end of the eighteenth century the attempts to produce malleable platinum had advanced mainly in the hands of practical men aiming at its pre paration and fabrication rather than at the solution of scientific problems. These were now to be attacked with a marked degree of success by two remarkable but very different men who first became friends during their student days at Cam bridge and who formed a working partnership in 1800 designed not only for scientific purposes but also for financial reasons. They were of the same genera tion and much the same background as the professional scientists of London whose work was described in Chapter 8, and to whom they were well known, but with the exception of Humphry Davy they were of greater stature and made a greater advance in the development of platinum metallurgy than their predecessors. Their combined achievements over a relatively short span of years included the successful production for the first time of malleable platinum on a truly com mercial scale as well as the discovery of no less than four new elements contained in native platinum, a factor that was of material help in the purification and treatment of platinum itself. -

Project Note Weston Solutions, Inc

PROJECT NOTE WESTON SOLUTIONS, INC. To: Canadian Radium & Uranium Corp. Site File Date: June 5, 2014 W.O. No.: 20405.012.013.2222.00 From: Denise Breen, Weston Solutions, Inc. Subject: Determination of Significant Lead Concentrations in Sediment Samples References 1. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Technical Guidance for Screening Contaminated Sediments. March 1998. [45 pages] 2. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Office of Emergency Response. Establishing an Observed Release – Quick Reference Fact Sheet. Federal Register, Volume 55, No. 241. September 1995. [7 pages] 3. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Inorganic Chemistry Division Commission on Atomic Weights and Isotopic Abundances. Atomic Weights of Elements: Review 2000. 2003. [120 pages] WESTON personnel collected six sediment samples (including one environmental duplicate sample) from five locations along the surface water pathway of the Canadian Radium & Uranium Corp. (CRU) site in May 2014. The sediment samples were analyzed for Target Analyte List (TAL) Metals and Stable Lead Isotopes. 1. TAL Lead Interpretation: In order to quantify the significance for Lead, Thallium and Mercury the following was performed: 1. WESTON personnel tabulated all available TAL Metal data from the May 2014 Sediment Sampling event. 2. For each analyte of concern (Lead, Thallium, and Mercury), the highest background concentration was selected and then multiplied by three. This is the criteria to find the significance of site attributable release as per Hazard Ranking System guidelines. 3. One analytical lead result (2222-SD04) of 520 mg/kg (J) was qualified with an unknown bias. In accordance with US EPA document “Using Data to Document an Observed Release and Observed Contamination”, 2222-SD03 lead concentration was adjusted by dividing by the factor value for lead of 1.44 to equal 361 mg/kg. -

William Hyde Wollaston Eric Clark

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core MicroscopyPioneers Pioneers in Optics: William Hyde Wollaston Eric Clark . IP address: From the website Molecular Expressions created by the late Michael Davidson and now maintained by Eric Clark, National Magnetic Field Laboratory, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306 170.106.202.226 [email protected] , on William Hyde Wollaston bladder stone that he named cystic oxide, later called cystine, the 03 Oct 2021 at 02:49:34 (1766–1828) first known amino acid. Twelve years later Wollaston provided The quantity and diversity the best contemporary physiological description of the ear. of William Hyde Wollaston’s Wollaston formed another alliance to perform chemis- research made him one of the try studies and experiments, this time with Smithson Tennant. most influential scientists of his Platinum had long evaded the efforts of chemists to concentrate , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at time. Although formally trained and purify the precious element, and the pair decided to join in as a physician, Wollaston studied the endeavor. When Tennant first tried to produce platinum, the and made advances in many sci- result was his discovery of the new elements iridium and osmium. entific fields, including chemistry, Wollaston’s later attempt led him to the discovery of palladium physics, botany, crystallography, and rhodium. He then invented the technique of powder metal- optics, astronomy, and mineral- lurgy and produced malleable platinum in 1805. The feat proved ogy. He is particularly noted for extremely profitable and provided him with financial indepen- being the first to observe dark lines dence for the rest of his life. -

Philosophical Transactions (A)

INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS (A) FOR THE YEAR 1889. A. A bney (W. de W.). Total Eclipse of the San observed at Caroline Island, on 6th May, 1883, 119. A bney (W. de W.) and T horpe (T. E.). On the Determination of the Photometric Intensity of the Coronal Light during the Solar Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 363. Alcohol, a study of the thermal properties of propyl, 137 (see R amsay and Y oung). Archer (R. H.). Observations made by Newcomb’s Method on the Visibility of Extension of the Coronal Streamers at Hog Island, Grenada, Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 382. Atomic weight of gold, revision of the, 395 (see Mallet). B. B oys (C. V.). The Radio-Micrometer, 159. B ryan (G. H.). The Waves on a Rotating Liquid Spheroid of Finite Ellipticity, 187. C. Conroy (Sir J.). Some Observations on the Amount of Light Reflected and Transmitted by Certain 'Kinds of Glass, 245. Corona, on the photographs of the, obtained at Prickly Point and Carriacou Island, total solar eclipse, August 29, 1886, 347 (see W esley). Coronal light, on the determination of the, during the solar eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 363 (see Abney and Thorpe). Coronal streamers, observations made by Newcomb’s Method on the Visibility of, Eclipse of August 28-29, 1886, 382 (see A rcher). Cosmogony, on the mechanical conditions of a swarm of meteorites, and on theories of, 1 (see Darwin). Currents induced in a spherical conductor by variation of an external magnetic potential, 513 (see Lamb). 520 INDEX. -

the Papers Philosophical Transactions

ABSTRACTS / OF THE PAPERS PRINTED IN THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LONDON, From 1800 to1830 inclusive. VOL. I. 1800 to 1814. PRINTED, BY ORDER OF THE PRESIDENT AND COUNCIL, From the Journal Book of the Society. LONDON: PRINTED BY RICHARD TAYLOR, RED LION COURT, FLEET STREET. CONTENTS. VOL. I 1800. The Croonian Lecture. On the Structure and Uses of the Meinbrana Tympani of the Ear. By Everard Home, Esq. F.R.S. ................page 1 On the Method of determining, from the real Probabilities of Life, the Values of Contingent Reversions in which three Lives are involved in the Survivorship. By William Morgan, Esq. F.R.S.................... 4 Abstract of a Register of the Barometer, Thermometer, and Rain, at Lyndon, in Rutland, for the year 1798. By Thomas Barker, Esq.... 5 n the Power of penetrating into Space by Telescopes; with a com parative Determination of the Extent of that Power in natural Vision, and in Telescopes of various Sizes and Constructions ; illustrated by select Observations. By William Herschel, LL.D. F.R.S......... 5 A second Appendix to the improved Solution of a Problem in physical Astronomy, inserted in the Philosophical Transactions for the Year 1798, containing some further Remarks, and improved Formulae for computing the Coefficients A and B ; by which the arithmetical Work is considerably shortened and facilitated. By the Rev. John Hellins, B.D. F.R.S. .......................................... .................................. 7 Account of a Peculiarity in the Distribution of the Arteries sent to the ‘ Limbs of slow-moving Animals; together with some other similar Facts. In a Letter from Mr. -

The Correspondence of Jane and Alexander Marcet During Its Writing

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 42, Number 2 (2017) 85 THE INTERNATIONAL PUBLICATION HISTORY OF CONVERSATIONS ON CHEMISTRY: THE CORRESPONDENCE OF JANE AND ALEXANDER MARCET DURING ITS WRITING G. J. Leigh, University of Sussex; [email protected] Abstract ning of the nineteenth century to write such an attractive, informed and authoritative account of contemporary Conversations on Chemistry was one of many books chemistry? She was not a chemist, and never claimed to on physical and biological sciences which appeared in be, and even those who might have identified Jane Marcet Britain from the beginning of the nineteenth century. (née Haldimand) as the author would have realized that There was a considerable market for public lecture in 1806 she was a woman in her early thirties who had courses, and writers and publishers encouraged this with hitherto betrayed no interest in the science. She was from books, often intended for self-study. Conversations on a wealthy family with social connections of the highest Chemistry was one of the most successful books of this order, yet she wrote a book on a subject of which she type, going through sixteen editions over about fifty apparently knew nothing, and she wrote it for the benefit years, and being widely copied, adapted and translated, of other women, for whom she had previously displayed often for audiences very different from that to which little concern. Jane Marcet was an unlikely pioneer in the it was originally directed. An account of the genesis popularization of chemistry, and of sciences, for people of this book based upon the notebooks of the author’s in general, let alone for women. -

The Scientific Publications of Alexander Marcet

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 43, Number 2 (2018) 61 THE SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS OF ALEXANDER MARCET G. J. Leigh, University of Sussex, [email protected], and Carmen J. Giunta, Le Moyne College, [email protected] Supplemental material Abstract 1808 when he was elected to the Royal Society. French was his native language and this enabled him to maintain This paper lists all the publications which can be contacts with French and Swiss researchers, and to act as attributed to Alexander Marcet, a physician, chemist foreign secretary to, for example, the Geological Society and geologist active during the first two decades of the of London. He died in 1822. His scientific activities show nineteenth century. The contents of each publication are how, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, chem- described and assessed. Marcet was a practicing physi- istry in Britain was professionally and institutionally cian at a time and place when many chemists had medical intertwined with medicine, even while other chemists connections. His chemical work is primarily analytical were breaking free from it. and it also demonstrates how chemistry might eventu- Detailed information on Alexander and Jane Marcet ally shed light on how the human body deals with the is still easily available, and Jane’s life, in particular, has materials it has ingested. been described in considerable detail (1). However, Alex- ander’s professional career has been relatively neglected. Introduction This paper is an attempt to illustrate that he was no mere helper to his exceptional wife, but a significant figure in Alexander Marcet (1770-1822) and his wife Jane his own right. -

Back Matter (PDF)

[ 529 ] INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS, Series A, V ol. 192. A. Algebraic Functions expressed as uniform Automorphic Functions (Whittaker), 1. Anatysis—Partition-linear, Diophantine-linear (MacMahon), 351. Automorphic Functions corresponding to Algebraic Relations (Whittaker), 1. B. Bramley-Moore (L.). See Pearson, Lee, and Bramley-Moore. C. Clouds, produced by Ultra-violet Light; Nuclei for the Production of (Wilson), 403. Condensation Nuclei, produced by Rontgen Rays, &c.; Degree of Supersaturation necessary for condensation; behaviour in Electric Field (Wilson), 403. Correlation between Long Bones and Stature (Pearson), 169. Crystals (quartz), gravitative Action between (Poynting and Gray), 245; thermal Expansion of (Tutton), 455. Curve of Error, Tables relating to (S heppard), 101, Cyclotomic Functions (MacMahon), 351. D. Differential Equations satisfied by Automorphic Functions (Whittaker), 1. YOL. CXCII.— A. 3 Y 530 INDEX. E. Kvolution, Mathematical Contributions to Theory of (P earson), 169, 257. F. Flames containing Salt Vapours, Electrical Conductivity of (Wilson), 499. G. Generating Functions, graphical representation of (MacMahon), 351. Goniometer, improved cutting and grinding, for preparation of Plates and Prisms of Crystals (Tutton), 455. Gravitation Constant of Quartz: an Experiment in Search of possible Differences (Poynting and Geay), 245. Geay (P. L.). See Poynting and Geay. H. IIicks (W. M.). Researches in Vortex Motion.—Part III. On Spiral or Gyrostatic Vortex Aggregates, 33. I. Inheritance of Fecundity, Fertility and Latent Characters (Peaeson, Lee, and Beamley-Mooee), 257. Ionic Velocities directly measured (Masson), 331. Ionisation of Salt Vapours in Flames (W ilson), 499. Ions, velocity in Flames and Hot Air (Wilson), 499. L. Lee (Alice). See Peaeson, Lee, and Beamley-Mooee. -

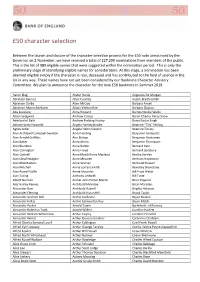

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner