Theorizing Bruce Lee's Action Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Va.Orgjackie's MOVIES

Va.orgJACKIE'S MOVIES Jackie starred in his first movie at the age of eight and has been making movies ever since. Here's a list of Jackie's films: These are the films Jackie made as a child: ·Big and Little Wong Tin-Bar (1962) · The Lover Eternal (1963) · The Story of Qui Xiang Lin (1964) · Come Drink with Me (1966) · A Touch of Zen (1968) These are films where Jackie was a stuntman only: Fist of Fury (1971) Enter the Dragon (1973) The Himalayan (1975) Fantasy Mission Force (1982) Here is the complete list of all the rest of Jackie's movies: ·The Little Tiger of Canton (1971, also: Master with Cracked Fingers) · CAST : Jackie Chan (aka Chen Yuen Lung), Juan Hsao Ten, Shih Tien, Han Kyo Tsi · DIRECTOR : Chin Hsin · STUNT COORDINATOR : Chan Yuen Long, Se Fu Tsai · PRODUCER : Li Long Koon · The Heroine (1971, also: Kung Fu Girl) · CAST : Jackie Chan (aka Chen Yuen Lung), Cheng Pei-pei, James Tien, Jo Shishido · DIRECTOR : Lo Wei · STUNT COORDINATOR : Jackie Chan · Not Scared to Die (1973, also: Eagle's Shadow Fist) · CAST : Wang Qing, Lin Xiu, Jackie Chan (aka Chen Yuen Lung) · DIRECTOR : Zhu Wu · PRODUCER : Hoi Ling · WRITER : Su Lan · STUNT COORDINATOR : Jackie Chan · All in the Family (1975) · CAST : Linda Chu, Dean Shek, Samo Hung, Jackie Chan · DIRECTOR : Chan Mu · PRODUCER : Raymond Chow · WRITER : Ken Suma · Hand of Death (1976, also: Countdown in Kung Fu) · CAST : Dorian Tan, James Tien, Jackie Chan · DIRECTOR : John Woo · WRITER : John Woo · STUNT COORDINATOR : Samo Hung · New Fist of Fury (1976) · CAST : Jackie Chan, Nora Miao, Lo Wei, Han Ying Chieh, Chen King, Chan Sing · DIRECTOR : Lo Wei · STUNT COORDINATOR : Han Ying Chieh · Shaolin Wooden Men (1976) · CAST : Jackie Chan, Kam Kan, Simon Yuen, Lung Chung-erh · DIRECTOR : Lo Wei · WRITER : Chen Chi-hwa · STUNT COORDINATOR : Li Ming-wen, Jackie Chan · Killer Meteors (1977, also: Jackie Chan vs. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 28

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 28 May 2003 6877 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 28 May 2003 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE KENNETH TING WOO-SHOU, J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID CHU YU-LIN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ERIC LI KA-CHEUNG, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LUI MING-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE NG LEUNG-SING, J.P. 6878 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 28 May 2003 THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE HUI CHEUNG-CHING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KWOK-KEUNG THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. -

James TIEN 田俊(B

James TIEN 田俊(b. 1942) Actor Born Chen Wen, Tien was from Chao’an, Guangdong. In 1958, he moved to Hong Kong with his family. Same as Angela Mao Ying, he graduated from Fu Hsing Dramatic Arts Academy in Taiwan. He worked as a stuntman at Shaw Brothers in the mid-1960s. In 1969, he gained fame by assisting director Lo Wei in shooting a kung fu movie; soon after, he appeared in Vengeance of a Snow Girl (1971) in which he was also the action choreographer. Tien joined Golden Harvest soon after it was established, and adopted the stage name James Tien since. He was the male lead in the company’s early works, such as The Invincible Eight (1971), The Blade Spares None (1971), The Chase (1971) and Thunderbolt (1973, filmed in 1971). He was also cast in Bruce Lee’s vehicles such as The Big Boss (1971) and Fist of Fury (1972). From A Man Called Tiger (1973) and Seaman No 7 (1973) onward, he was often seen playing the villain; thereafter, he starred in a number of kung fu films, such as Shaolin Boxers (1974), The Dragon Tamers (1975), Hand of Death (1976) and The Shaolin Plot (1977). In 1978, Tien began to work for Lo Wei Motion Picture Co., Ltd., appearing in the Jackie Chan-starring Magnificent Bodyguards (1978), Spiritual Kung Fu (1978) and Dragon Fist (1979), all produced in Taiwan. Tien remained active throughout the 1980s, mostly taking part in Golden Harvest projects, including Winners & Sinners (1983), Twinkle, Twinkle, Lucky Stars (1985), Heart of Dragon (1985), The Millionaires’ Express (1986), Eastern Condors (1987) and Super Lady Cop (1992). -

2016 Country Review

China 2016 Country Review http://www.countrywatch.com Table of Contents Chapter 1 1 Country Overview 1 Country Overview 2 Key Data 3 China 4 Asia 5 Chapter 2 7 Political Overview 7 History 8 Political Conditions 13 Political Risk Index 54 Political Stability 68 Freedom Rankings 84 Human Rights 95 Government Functions 99 Government Structure 100 Principal Government Officials 104 Leader Biography 105 Leader Biography 105 Foreign Relations 118 National Security 145 Defense Forces 148 Appendix: Hong Kong 150 Appendix: Taiwan 173 Appendix: Macau 208 Chapter 3 220 Economic Overview 220 Economic Overview 221 Nominal GDP and Components 224 Population and GDP Per Capita 226 Real GDP and Inflation 227 Government Spending and Taxation 228 Money Supply, Interest Rates and Unemployment 229 Foreign Trade and the Exchange Rate 230 Data in US Dollars 231 Energy Consumption and Production Standard Units 232 Energy Consumption and Production QUADS 234 World Energy Price Summary 236 CO2 Emissions 237 Agriculture Consumption and Production 238 World Agriculture Pricing Summary 241 Metals Consumption and Production 242 World Metals Pricing Summary 245 Economic Performance Index 246 Chapter 4 258 Investment Overview 258 Foreign Investment Climate 259 Foreign Investment Index 261 Corruption Perceptions Index 274 Competitiveness Ranking 285 Taxation 294 Stock Market 296 Partner Links 297 Chapter 5 298 Social Overview 298 People 299 Human Development Index 305 Life Satisfaction Index 309 Happy Planet Index 320 Status of Women 329 Global Gender Gap Index 333 Culture -

Hong Kong: Ten Years After the Handover

Order Code RL34071 Hong Kong: Ten Years After the Handover June 29, 2007 Michael F. Martin Analyst in Asian Political Economics Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Hong Kong: Ten Years After the Handover Summary In the 10 years that have passed since the reversion of Hong Kong from British to Chinese sovereignty, much has changed and little has changed. On the political front, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) has selected its first Chief Executive, only to have him step down and be replaced in a process not without some controversy. Meanwhile, belated changes by the British in the makeup of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council (Legco) were initially undone, but subsequent changes in the Legco selection process have brought things back nearly full circle to where they stood prior to the Handover. There is also unease about the independence of Hong Kong’s judicial system and the protection provided by Hong Kong’s Basic Law in light of decisions made by the Chinese government. Similarly, the civil liberties of the people of Hong Kong remain largely intact. In part, this can be attributed to the increased politicization of the people of Hong Kong. The freedom of the press in Hong Kong is still strong, but also faces challenges — both on the legal front and from allegations of self-censorship on the part of the media owners reluctant to antagonize the People’s Republic of China. Yet, even with these challenges, many Hong Kong residents do not appear to perceive a decline in their civil liberties since 1997. -

14 Martial Arts Movies Every Guy Should See Ip

Best Martial Art Movie 14 Martial Arts Movies Every Guy Should See Share F O L L O W C M Disable wpStickies on this image Few things are as delectably enjoyable as martial arts films. You can turn most on half way through and still get glued to your couch. You coast along with the plot (as awful as it can be at times) eagerly anticipating the next fight scene. Great martial arts flicks, however, combine awesome combat with a story that actually makes it worth the down time between roundhouse kicks. Here are 14 every guys should see. Ip Man The fight scenes in Ip Man are so devastatingly awesome, you’ll want to start training in Wing Chun as soon as the credits roll. Bruce Lee’s mentor, as played by Donnie Yen, is soft-spoken, kind, and insanely badass when it comes to combat. Ip Man is not just a watch-worthy flick because of the great fight scenes, but it’s also an interesting historical look at the world Ip Man lived in and what life was like in 1930’s Southern China. Plus, any dude who trained Bruce Lee must be pretty decent, right? Amazon Instant iTunes Netflix Instant Netflix DVD Hero For as awesome as Jet Li is, a lot of his films fall short for us. Hero is one major exception (along with Once Upon a Time in China). The first thing you’ll notice about Hero is the sheer beauty of it. Not just the choreographed fight scenes, but just the overall look. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 22

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 22 January 2014 5719 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 22 January 2014 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. 5720 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 22 January 2014 THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONNY TONG KA-WAH, S.C. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. -

Tae Kwon Do Kampfsport-Filme

TTaaee KKwwoonn DDoo KKaammppffssppoorrtt--FFiillmmee www.Carbon-Sport.de www.Carbon-Music.de Kampfsport-Filme / Eastern: Eastern (von englisch east: Osten) ist ein beliebtes Filmgenre das sich mit asiatischer Kampfkunst und der dazugehörigen Philosophie beschäftigt. Eastern werden auch als Kampfsport-Filme oder auch Kung Fu-Filme (mit denen alles begann) bezeichnet. Eastern gibt es bereits seit dem Anfang der Filmgeschichte. Die ersten Eastern stammen aus Asien, seit den 80er Jahren gibt es allerdings auch viele amerikanische Eastern. Eastern lassen sich wiederum in mehrere Sub-Genres unterteilen: Martial-Arts-Filme: Filme, die mit einem Schwerpunkt auf die Darstellung von Kampfszenen unter das Genre des Actionfilms oder auch Action-Komödie fallen. Dazu zählen Kung- Fu- (Shaolin Kung Fu-), Tae Kwon Do-, Karate-, Muay Thai- und Kickbox-Filme. Kung Fu-Filme sind hier deutlich in der Überzahl und mit ihnen fing alles an. Ninja-Filme: Filme, in denen Ninjas vorkommen. Ninja (von japanisch Ninja = Jemand im Geheimen), ein Schattenkrieger des vorindustriellen Japans, der als Kundschafter, Spion, Saboteur oder Meuchelmörder eingesetzt wurde. Er ist neben dem Samurai eine der gefürchtetsten und gleichzeitig am meisten bewunderten Gestalten des alten Japan. Die Kampfsportart der Ninja nennt man Ninjutsu. Samurai-Filme: Filme, in denen Samurai vorkommen. Die Samurai oder auch Bushi genannt, waren Mitglieder des Kriegerstandes im vorindustriellen Japan. Ninja-Filme erfreuen sich aber einer größeren Beliebtheit, da der Ninja ein geheimnisvoller und mystischer Schattenkrieger ist. Ein willenloses Werkzeug seines Herrn, der aus dem Nichts auftauchte, seinen Auftrag erfüllte und unerkannt abtauchte. Dieses unerkannte Operieren und die Ausübung als Meuchelmörder ist der Grund für den Gegensatz des „ehrvollen“, adligen Samurai und des „ehrlosen“, gefürchteten Ninja. -

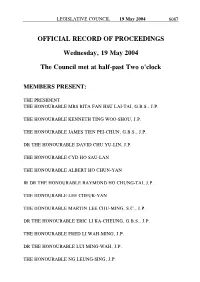

Official Record of Proceedings of A

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 19 May 2004 6087 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 19 May 2004 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE KENNETH TING WOO-SHOU, J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID CHU YU-LIN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE ERIC LI KA-CHEUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LUI MING-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE NG LEUNG-SING, J.P. 6088 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 19 May 2004 THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KWOK-KEUNG, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HOWARD YOUNG, S.B.S., J.P. -

Bruce Lee Filme“ Im Kino

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Hauck Einfluss des Hongkongkinos auf den Hollywood-Actionfilm 2014 Fakultät Medien BACHELORARBEIT Einfluss des Hongkongkinos auf den Hollywood-Actionfilm Autor: Herr Benjamin Hauck Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08s1-B Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Robert Wierzbicki Zweitprüfer: BA-MA (Asian Studies / Sophia University Tokyo) Karin Maichel-Ritter Einreichung: Müncher, 19.06.2014 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS Influence of Hongkong-movies on Hollywoods actionfilms author: Mr. Benjamin Hauck course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08s1-B first examiner: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Robert Wierzbicki second examiner: BA-MA (Asian Studies / Sophia University Tokyo) Karin Maichel-Ritter submission: Munich, 19.06.2014 IV Bibliografische Angaben: Nachname, Vorname: Benjamin Hauck Thema der Bachelorarbeit: Einfluss des Hongkongkinos auf den Hollywood-Actionfilm Topic of thesis: Influence of Hongkongmovies on Hollywoods actionfilms 2014 - 55 Seiten Mittweida, Hochschule Mittweida (FH), University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2014 V Inhaltsverzeichnis Abbildungsverzeichnis...........................................................................................VII 1 Zielsetzung..............................................................................................................1 2 Der Ursprung des Martial Arts Films.....................................................................3 2.1 Wuxia Film........................................................................................................3 -

Official Record of Proceedings

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL - 28 July 1995 6335 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Friday, 28 July 1995 The Council met at Nine o’clock PRESENT THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE SIR JOHN SWAINE, C.B.E., LL.D., Q.C., J.P. THE CHIEF SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE MRS ANSON CHAN, C.B.E., J.P. THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE SIR NATHANIEL WILLIAM HAMISH MACLEOD, K.B.E., J.P. THE ATTORNEY GENERAL THE HONOURABLE JEREMY FELL MATHEWS, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, Q.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE NGAI SHIU-KIT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PANG CHUN-HOI, M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE SZETO WAH THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EDWARD HO SING-TIN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE RONALD JOSEPH ARCULLI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARTIN GILBERT BARROW, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS PEGGY LAM, O.B.E., J.P. 6336 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL - 28 July 1995 THE HONOURABLE MRS MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WAH-SUM, O.B.E., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEONG CHE-HUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES DAVID McGREGOR, O.B.E., I.S.O., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS ELSIE TU, C.B.E. -

The Big Boss, Fist of Fury, Distributor Mediumrare the Way of the Dragon and Game of Death

31 Southampton Row, London WC1B 5HJ Tel: 0203 585 1396 Web: fetch.fm PRESS RELEASE When it comes to martial arts cinema, one name stands above all others – Bruce Lee. Not only one of cinema’s most phenomenally talented physical performers, he also possessed a star aura that transcended cult status to make Bruce Lee one the great icons of pop culture. RELEASE INFORMATION Now, four of his greatest films are coming to dual DVD & Blu-ray October 26th – The Big Boss, Fist of Fury, Distributor Mediumrare The Way of the Dragon and Game of Death. All Entertainment landmarks in the martial arts cinema and integral to the ________________________________________________ legend of Bruce Lee! Certificate 18 ________________________________________________ THE BIG BOSS Release date 26th October CONTACT/ORDER MEDIA The film that began Bruce Lee’s legacy as the world’s greatest martial arts star! Thomas Hewson - [email protected] Bruce Lee’s first major role and the movie that made him a star across Asia. He plays a man who uncovers a drug smuggling ring after his cousins mysteriously disappear. With a brilliant performance from Lee, plus his incredible trademark fighting, it’s a true martial arts classic! Key talent: Bruce Lee (Fist of Fury, Enter The Dragon, Way of the Dragon) Nora Miao (Fist of Fury, Way of the Dragon) James Tien (Fist of Fury, Game of Death, The Fearless Hyena) Tony Liu (Way of the Dragon, Fist of Fury, Revenge: A Love Story) Yien Chieh-han (Fist of Fury, The End of the Wicked Tiger) Synopsis: When Cheng Chao-an (Bruce Lee) travels to stay with extended family Thailand, he takes a job with his cousins in an ice factory.