Strategic Consensus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants

JUNE 26–30, Prague • Andrzej Kremer, Delegation of Poland, Poland List of Participants • Andrzej Relidzynski, Delegation of Poland, Poland • Angeles Gutiérrez, Delegation of Spain, Spain • Aba Dunner, Conference of European Rabbis, • Angelika Enderlein, Bundesamt für zentrale United Kingdom Dienste und offene Vermögensfragen, Germany • Abraham Biderman, Delegation of USA, USA • Anghel Daniel, Delegation of Romania, Romania • Adam Brown, Kaldi Foundation, USA • Ann Lewis, Delegation of USA, USA • Adrianus Van den Berg, Delegation of • Anna Janištinová, Czech Republic the Netherlands, The Netherlands • Anna Lehmann, Commission for Looted Art in • Agnes Peresztegi, Commission for Art Recovery, Europe, Germany Hungary • Anna Rubin, Delegation of USA, USA • Aharon Mor, Delegation of Israel, Israel • Anne Georgeon-Liskenne, Direction des • Achilleas Antoniades, Delegation of Cyprus, Cyprus Archives du ministère des Affaires étrangères et • Aino Lepik von Wirén, Delegation of Estonia, européennes, France Estonia • Anne Rees, Delegation of United Kingdom, United • Alain Goldschläger, Delegation of Canada, Canada Kingdom • Alberto Senderey, American Jewish Joint • Anne Webber, Commission for Looted Art in Europe, Distribution Committee, Argentina United Kingdom • Aleksandar Heina, Delegation of Croatia, Croatia • Anne-Marie Revcolevschi, Delegation of France, • Aleksandar Necak, Federation of Jewish France Communities in Serbia, Serbia • Arda Scholte, Delegation of the Netherlands, The • Aleksandar Pejovic, Delegation of Monetenegro, Netherlands -

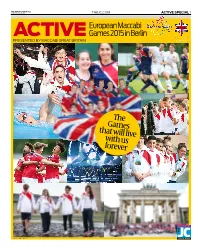

The Games That Will Live with Us Forever

THE JEWISH CHRONICLE 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 THEJC.COM ACTIVE SPECIAL 1 European Maccabi ACTIVE Games 2015 in Berlin PRESENTED BY MACCABI GREAT BRITAIN The Games that will live with us forever MEDIA partner PHOTOS: MARC MORRIS THE JEWISH CHRONICLE THE JEWISH CHRONICLE 2 ACTIVE SPECIAL THEJC.COM 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 THEJC.COM ACTIVE SPECIAL 3 ALL ALL WORDS PHOTOS WELCOME BY DAnnY BY MARC CARO MORRIS Maccabi movement’s ‘miracle’ in Berlin LDN Investments are proud to be associated with Maccabi GB and the success of the European Maccabi Games in Berlin. HIS SUMMER, old; athletes and their families; reuniting THE MACCABI SPIRIT place where they were banished from first night at the GB/USA Gala Dinner, “By SOMETHING hap- existing friendships and creating those Despite the obvious emotion of the participating in sport under Hitler’s winning medals we have not won. By pened which had anew. Friendships that will last a lifetime. Opening Ceremony, the European Mac- reign was a thrill and it gave me an just being here in Berlin we have won.” never occurred But there was also something dif- cabi Games 2015 was one big party, one enormous sense of pride. We will spread the word, keep the before. For the first ferent about these Games – something enormous celebration of life and of Having been there for a couple of days, torch of love, not hate, burning bright. time in history, the that no other EMG has had before it. good triumphing over evil. Many thou- my hate of Berlin turned to wonder. -

2018–2019 Annual Report

18|19 Annual Report Contents 2 62 From the Chairman of the Board Ensemble Connect 4 66 From the Executive and Artistic Director Digital Initiatives 6 68 Board of Trustees Donors 8 96 2018–2019 Concert Season Treasurer’s Review 36 97 Carnegie Hall Citywide Consolidated Balance Sheet 38 98 Map of Carnegie Hall Programs Administrative Staff Photos: Harding by Fadi Kheir, (front cover) 40 101 Weill Music Institute Music Ambassadors Live from Here 56 Front cover photo: Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer, by Stephanie Berger. Stephanie by Chris “Critter” Eldridge, and Chris Thile National Youth Ensembles in Live from Here March 9 Daniel Harding and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra February 14 From the Chairman of the Board Dear Friends, In the 12 months since the last publication of this annual report, we have mourned the passing, but equally importantly, celebrated the lives of six beloved trustees who served Carnegie Hall over the years with the utmost grace, dedication, and It is my great pleasure to share with you Carnegie Hall’s 2018–2019 Annual Report. distinction. Last spring, we lost Charles M. Rosenthal, Senior Managing Director at First Manhattan and a longtime advocate of These pages detail the historic work that has been made possible by your support, Carnegie Hall. Charles was elected to the board in 2012, sharing his considerable financial expertise and bringing a deep love and further emphasize the extraordinary progress made by this institution to of music and an unstinting commitment to helping the aspiring young musicians of Ensemble Connect realize their potential. extend the reach of our artistic, education, and social impact programs far beyond In August 2019, Kenneth J. -

Rome International Conference on the Responsibility of States, Institutions and Individuals in the Fight Against Anti-Semitism in the OSCE Area

Rome International Conference on the Responsibility of States, Institutions and Individuals in the Fight against Anti-Semitism in the OSCE Area Rome, Italy, 29 January 2018 PROGRAMME Monday, 29 January 10.00 - 10.30 Registration of participants and welcome coffee 10.45 - 13.30 Plenary session, International Conference Hall 10.45 - 11.30 Opening remarks: - H.E. Angelino Alfano, Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, OSCE Chairperson-in-Office - H.E. Ambassador Thomas Greminger, OSCE Secretary General - H. E. Ingibjörg Sólrún Gísladóttir, ODIHR Director - Ronald Lauder, President, World Jewish Congress - Moshe Kantor, President, European Jewish Congress - Noemi Di Segni, President, Union of the Italian Jewish Communities 11.30 – 13.00 Interventions by Ministers 13.00 - 13.30 The Meaning of Responsibility: - Rabbi Israel Meir Lau, Chairman of Yad Vashem Council - Daniel S. Mariaschin, CEO B’nai Brith - Prof. Andrea Riccardi, Founder of the Community of Sant’Egidio 13.30 - 14.15 Lunch break - 2 - 14.15 - 16.15 Panel 1, International Conference Hall “Responsibility: the role of law makers and civil servants” Moderator: Maurizio Molinari, Editor in Chief of the daily La Stampa Panel Speakers: - David Harris’s Video Message, CEO American Jewish Committee - Cristina Finch, Head of Department for Tolerance and Non- discrimination, ODHIR - Katharina von Schnurbein, Special Coordinator of EU Commission on Anti-Semitism - Franco Gabrielli, Chief of Italian Police - Ruth Dureghello, President of Rome Jewish Community - Sandro De -

Nazi-Confiscated Art Issues

Nazi-Confiscated Art Issues Dr. Jonathan Petropoulos PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, LOYOLA COLLEGE, MD UNITED STATES Art Looting during the Third Reich: An Overview with Recommendations for Further Research Plenary Session on Nazi-Confiscated Art Issues It is an honor to be here to speak to you today. In many respects it is the highpoint of the over fifteen years I have spent working on this issue of artworks looted by the Nazis. This is a vast topic, too much for any one book, or even any one person to cover. Put simply, the Nazis plundered so many objects over such a large geographical area that it requires a collaborative effort to reconstruct this history. The project of determining what was plundered and what subsequently happened to these objects must be a team effort. And in fact, this is the way the work has proceeded. Many scholars have added pieces to the puzzle, and we are just now starting to assemble a complete picture. In my work I have focused on the Nazi plundering agencies1; Lynn Nicholas and Michael Kurtz have worked on the restitution process2; Hector Feliciano concentrated on specific collections in Western Europe which were 1 Jonathan Petropoulos, Art as Politics in the Third Reich (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press). Also, The Faustian Bargain: The Art World in Nazi Germany (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming, 1999). 2 Lynn Nicholas, The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe's Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1994); and Michael Kurtz, Nazi Contraband: American Policy on the Return of European Cultural Treasures (New York: Garland, 1985). -

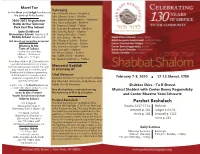

Parshat Beshalach

Mazel Tov Yahrzeits to the Dror and Sedgh families on Mrs. Marcelle Faust - Husband the birth of Mika Rachel. Mrs. Marion Gross - Mother 2020-2021 Registration Mrs. Batya Kahane Hyman - Husband Rabbi Arthur Schneier Mrs. Rose Lefkowitz - Brother Mr. Seymour Siegel - Father Park East Day School Mr. Leonard Brumberg - Mother Early Childhood Mrs. Ginette Reich - Mother Elementary School: Grades 1-5 Mr. Harvey Drucker - Father Middle School: Grades 6-8 Mr. Jack Shnay - Mother Ask about our incentive program! Mrs. Marjorie Schein - Father Mr. Andrew Feinman - Father Mommy & Me Mrs. Hermine Gewirtz - Sister Taste of School Mrs. Iris Lipke - Mother Tuesday and Thursday Mr. Meyer Stiskin - Father 9:00 am - 10:30 am or 10:45 am - 12:15 pm Ms. Judith Deich - Mother Mr. Joseph Guttmann - Father Providing children 14-23 months with a wonderful introduction to a more formal learning environment. Through Memorial Kaddish play, music, art, movement, and in memory of Shabbat and holiday programming, children learn to love school and Ethel Kleinman prepare to separate from their beloved mother of our devoted members February 7-8, 2020 u 12-13 Shevat, 5780 parents/caregivers. Elly (Shaindy) Kleinman, Leah Zeiger and Register online at ParkEastDaySchool.org Rabbi Yisroel Kleinman. Shabbat Shira - Tu B’Shevat or email [email protected] May the family be comforted among Musical Shabbat with Cantor Benny Rogosnitzky Leon & Gina Fromer the mourners of Zion & Jerusalem. Youth Enrichment Center and Cantor Maestro Yossi Schwartz Hebrew School Parshat Beshalach Pre-K (Age 4) This Shabbat is known as Shabbat Shira Parshat Beshalach Kindergarten (Age 5) because the highlight of the Torah Reading Exodus 13:17-17:16 Haftarah Elementary School (Ages 6-12) is the Song at the Sea. -

The Ronald S. Lauder Collection Selections from the 3Rd Century Bc to the 20Th Century Germany, Austria, and France

000-000-NGRLC-JACKET_EINZEL 01.09.11 10:20 Seite 1 THE RONALD S. LAUDER COLLECTION SELECTIONS FROM THE 3RD CENTURY BC TO THE 20TH CENTURY GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND FRANCE PRESTEL 001-023-NGRLC-FRONTMATTER 01.09.11 08:52 Seite 1 THE RONALD S. LAUDER COLLECTION 001-023-NGRLC-FRONTMATTER 01.09.11 08:52 Seite 2 001-023-NGRLC-FRONTMATTER 01.09.11 08:52 Seite 3 THE RONALD S. LAUDER COLLECTION SELECTIONS FROM THE 3RD CENTURY BC TO THE 20TH CENTURY GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND FRANCE With preface by Ronald S. Lauder, foreword by Renée Price, and contributions by Alessandra Comini, Stuart Pyhrr, Elizabeth Szancer Kujawski, Ann Temkin, Eugene Thaw, Christian Witt-Dörring, and William D. Wixom PRESTEL MUNICH • LONDON • NEW YORK 001-023-NGRLC-FRONTMATTER 01.09.11 08:52 Seite 4 This catalogue has been published in conjunction with the exhibition The Ronald S. Lauder Collection: Selections from the 3rd Century BC to the 20th Century. Germany, Austria, and France Neue Galerie New York, October 27, 2011 – April 2, 2012 Director of publications: Scott Gutterman Managing editor: Janis Staggs Editorial assistance: Liesbet van Leemput Curator, Ronald S . Lauder Collection: Elizabeth Szancer K ujawski Exhibition designer: Peter de Kimpe Installation: Tom Zoufaly Book design: Richard Pandiscio, William Loccisano / Pandiscio Co. Translation: Steven Lindberg Project coordination: Anja Besserer Production: Andrea Cobré Origination: royalmedia, Munich Printing and Binding: APPL aprinta, W emding for the text © Neue Galerie, New Y ork, 2011 © Prestel Verlag, Munich · London · New Y ork 2011 Prestel, a member of V erlagsgruppe Random House GmbH Prestel Verlag Neumarkter Strasse 28 81673 Munich +49 (0)89 4136-0 Tel. -

Remembering the Shoah the Icrc and the International Community’S Efforts in Responding to Genocide and Protecting Civilians

REMEMBERING THE SHOAH THE ICRC AND THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY’S EFFORTS IN RESPONDING TO GENOCIDE AND PROTECTING CIVILIANS A program organized by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the World Jewish Congress, Geneva, April 28, 2015 Remembering the Shoah: The ICRC and the International Community’s Efforts in Responding to Genocide and Protecting Civilians © by the World Jewish Congress and the International Committee of the Red Cross All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or reprinted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from either the World Jewish Congress or the International Committee of the Red Cross. ISBN: 978-0-9969361-0-1 Cover and Interior Design: Dorit Tabak [www.TabakDesign.com] World Jewish Congress 501 Madison Avenue, 9th Floor New York, NY 10022 International Committee of the Red Cross 19 Avenue de la Paix CH 1202 Geneva Cover: World Jewish Congress President Ronald S. Lauder addressing the “Remembering the Shoah” Conference at the Humanitarium of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, Switzerland, April 28, 2015. © Shahar Azran REMEMBERING THE ICRC AND THE THE SHOAH INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY’S EFFORTS IN RESPONDING TO GENOCIDE AND PROTECTING CIVILIANS Respect for the past, “responsibility for the future Seventy years after the liberation of the Nazi camps, how far have we come in terms of genocide prevention and civilian protection?” n April 28, 2015, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the World Jewish Congress held an event in the OHumanitarium at ICRC headquarters in Geneva to mark 70 years since the end of the Shoah, which saw the death of millions of Jews as the result of a systematic genocidal policy. -

Jewish National Fund 2020 Campaign Plan

Jewish National Fund 2020 Campaign Plan Dr. Sol Lizerbram Jeffrey E. Levine Ronald S. Lauder Russell F. Robinson President Chairman of the Board Chairman of the Board Chief Executive Officer Emeritus Benjamin Gutmann Richard T. Krosnick Vice President, Campaign Chief Development Officer October 1, 2019 Dear JNF Campaign Leaders: I am honored to have the opportunity to lead the Jewish National Fund 2020 annual Campaign. We continue with our $1 billion 10-year goal and look to surpass the $700 million mark by the end of the 2020 campaign year. Jewish National Fund has had unparalleled growth, and like any good business, we need to continue reviewing our operations and look for creative and thoughtful opportunities to expand. We restructured our national Major Gifts department with senior Jewish National Fund fundraisers working in partnership with our Major Gifts Committee. That group will support local community efforts to cultivate and solicit major donors and will improve communications around the country to enhance information-sharing about donors and prospects. This past year, the Major Gifts Committee undertook a study of our database to look at trends, growth of giving and donor recognition. The number of donors giving $5,000 or more has exploded to such a degree that we can no longer provide recognition at American Independence Park for $5,000 level donors -- we are simply running out of space. Therefore, beginning with this 2020 campaign year, recognition at American Independence Park will start at $10,000, with the exception of our Women for Israel Sapphire Society donors. We need at least 10,000 individual donors contributing $1,000 or more. -

Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern Europe Federal Republic of Germany National Affairs J_ HE ADOPTION OF A NEW capital city was only one transition among many that transformed the Bonn Republic into the Berlin Republic in 1999. In the spring, usually vocal intellectuals of the left watched in stunned silence as Chancellor Gerhard Schroder of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), and For- eign Minister Joschka Fischer, the leader of the Greens, led Germany into its first military engagement since World War II. For decades, pacifism had been the les- son drawn by the German left from Auschwitz, yet Fischer justified his support for the NATO bombing campaign in the Balkans by comparing Serbian crimes in Kosovo to the Holocaust. For his part, the "war chancellor" believed that the military engagement marked the dawn of a new age in which the German role on the world stage would reflect its economic strength. Finance Minister Oskar Lafontaine shocked his loyal followers in the SPD in March when he resigned from both his government post and the chairmanship of the party. His retreat ended months of conflict within the government over eco- nomic policy. In addition to appointing a minister of finance more amenable to neoliberal thinking, the chancellor reluctantly assumed the chairmanship of the SPD. Then, when the government announced plans in the summer to tighten the reins on government spending, the left wing of the SPD revolted, and Schroder needed months to silence traditionalists within his own party. This crisis within the SPD and the disillusionment of rank-and-file Greens with the performance of their party in the coalition translated into dismal returns for the governing parties in state elections throughout the year. -

9"E7<8.E8 ;<#1#)7 <; );4.7 E;<.41;8 4;.79;<.41;<( ,1(1/<)8.E97&7& 9<;/7

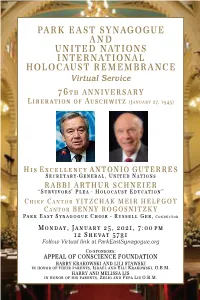

-<9"E7<8.E8 ;<#1#)7 < ; );4.7E;<.41;8 4;.79;<.41;<( ,1(1/<)8.E97&7&9<;/7 Virtual Service B2 <;;4798<9 (?D=CB?A>EAE<6@02?B C>6C=+E!$E ,?@ 70D::D>0+ <;.1;41 #).79978 8D0=DBC=+#D>D=C:$E)>?BD3E;CB?A>@E 9<4E<9.,)9E8/,;7479 86='?'A=@E-:DCEE,A:A0C6@BE7360CB?A> E / , 4 7 / < ; . 1 9 4./,<"E&749E,7(#1. / < ; . 1 9 7;; E91#18;4." -C=E7C@BE8+>C%A%6DE/2A?=EE96@@D::E#D=$ / A > 3 6 0 B A= &A>3C+$EC>6C=+E!$E!!$E *5 !E82D'CBE Follow Virtual link at ParkEastSynagogue.org /A@*A>@A=@ <--7<(E1E/1;8/47;/7E1);<.41; ,<99 E"9<"18"4E<;E(4(4E8.<8"4 ?>E2A>A=EAEB2D?=E*C=D>B@$E4@=CD:EC>3E7::?E"=CA@?$E1& ,<99 E<;E&7(488<E(48 ?>E2A>A=EAE2?@E*C=D>B@$ED:?%EC>3E-D*CE(?@E1& ?=B6C:E8D='?0D Presiding Rabbi Arthur Schneier Senior Rabbi, Park East Synagogue; Founder and President, Appeal of Conscience Foundation Mizmor L’David – The Lord is my Shepherd (Psalm 23) Park East Synagogue Choir; Russell Ger, Conductor Shema Yisrael – Hear ‘O Israel (Keynote Prayer) Etz Chaim – Tree of Life Cantor Benny Rogosnitzky Rabbi Arthur Schneier Holocaust Survivor “Survivors Plea - Holocaust Educ ation” His Excellency Antonio Guterres Secretary-General, United Nations Kel Maleh Rachamim – Memorial Prayer Chief Cantor Yitzchak Meir Helfgot Memorial Kaddish Rabbi Arthur Schneier Ani Ma’amin – Prayer of Faith Ose Shalom – A Prayer for Peace Children of the Rabbi Arthur Schneier Park East Day School and Park East Synagogue Nadav, Asaf, Yuval Osterweil, Sophie Gut, Larkin Horowitz and Danielle Rapport Violinist: Yuval Osterweil - Pianist: Sam Nakon 2 Vice President Joseph R. -

Terrorist in Training: the Role of Social Media and the Rise of Terrorism Through Nationalistic White Agenda

Advanced Release 2020 • Volume 8 THE JOURNAL OF CAMPUS BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTION Terrorist in Training: The Role of Social Media and the Rise of Terrorism through Nationalistic White Agenda Authors Lisa Pescara-Kovach, Ph.D. Associate Professor, University of Toledo [email protected] Brian Van Brunt, Ed.D. Partner, TNG | President, NaBITA [email protected] Amy Murphy, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Angelo State University [email protected] Abstract The U.S. political landscape is increasingly divided, fueled in part by the indignant, caustic, and divisive language used in our social media and online conversations. The authors examine a subset of white males who feel marginalized and powerless as they hear messaging advancing tolerance, diversity, equality, and political correctness. This in turn has fueled vocal and strident opposition to mass immigration, rage over the disappearance of a so-called pure culture of Germans and Europeans, and an underlying fear at the prospect of losing their history and heritage. The open nature of social media has provided a safe haven for our youth to be radicalized by those espousing Generation Identity and Alt-Right ideologies, euphemisms for white supremacist thought and Nazism. The authors explore this trend through the recent terroristic actions in El Paso, Texas, Charleston, South Carolina and the related events of Oslo, Norway and Christchurch, New Zealand. 1 2020 • VOLUME 8 Introduction propensity for violence. January 27, 2020 marked the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp where 1.1 million innocent people The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), created in 1913 to address died in a span of five years (Gera, 2020).