Central and Eastern Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants

JUNE 26–30, Prague • Andrzej Kremer, Delegation of Poland, Poland List of Participants • Andrzej Relidzynski, Delegation of Poland, Poland • Angeles Gutiérrez, Delegation of Spain, Spain • Aba Dunner, Conference of European Rabbis, • Angelika Enderlein, Bundesamt für zentrale United Kingdom Dienste und offene Vermögensfragen, Germany • Abraham Biderman, Delegation of USA, USA • Anghel Daniel, Delegation of Romania, Romania • Adam Brown, Kaldi Foundation, USA • Ann Lewis, Delegation of USA, USA • Adrianus Van den Berg, Delegation of • Anna Janištinová, Czech Republic the Netherlands, The Netherlands • Anna Lehmann, Commission for Looted Art in • Agnes Peresztegi, Commission for Art Recovery, Europe, Germany Hungary • Anna Rubin, Delegation of USA, USA • Aharon Mor, Delegation of Israel, Israel • Anne Georgeon-Liskenne, Direction des • Achilleas Antoniades, Delegation of Cyprus, Cyprus Archives du ministère des Affaires étrangères et • Aino Lepik von Wirén, Delegation of Estonia, européennes, France Estonia • Anne Rees, Delegation of United Kingdom, United • Alain Goldschläger, Delegation of Canada, Canada Kingdom • Alberto Senderey, American Jewish Joint • Anne Webber, Commission for Looted Art in Europe, Distribution Committee, Argentina United Kingdom • Aleksandar Heina, Delegation of Croatia, Croatia • Anne-Marie Revcolevschi, Delegation of France, • Aleksandar Necak, Federation of Jewish France Communities in Serbia, Serbia • Arda Scholte, Delegation of the Netherlands, The • Aleksandar Pejovic, Delegation of Monetenegro, Netherlands -

Theresienstadt Concentration Camp from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Theresienstadt concentration camp From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E "Theresienstadt" redirects here. For the town, see Terezín. Navigation Theresienstadt concentration camp, also referred to as Theresienstadt Ghetto,[1][2] Main page [3] was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress and garrison city of Contents Terezín (German name Theresienstadt), located in what is now the Czech Republic. Featured content During World War II it served as a Nazi concentration camp staffed by German Nazi Current events guards. Random article Tens of thousands of people died there, some killed outright and others dying from Donate to Wikipedia malnutrition and disease. More than 150,000 other persons (including tens of thousands of children) were held there for months or years, before being sent by rail Interaction transports to their deaths at Treblinka and Auschwitz extermination camps in occupied [4] Help Poland, as well as to smaller camps elsewhere. About Wikipedia Contents Community portal Recent changes 1 History The Small Fortress (2005) Contact Wikipedia 2 Main fortress 3 Command and control authority 4 Internal organization Toolbox 5 Industrial labor What links here 6 Western European Jews arrive at camp Related changes 7 Improvements made by inmates Upload file 8 Unequal treatment of prisoners Special pages 9 Final months at the camp in 1945 Permanent link 10 Postwar Location of the concentration camp in 11 Cultural activities and -

7. Österreichischer Zeitgeschichtetag 2008

7. Österreichischer Zeitgeschichtetag 2008 Innsbruck 28.–31. Mai 2008 • Die 1960er und 1970er und die Folgen • Bestandsaufnahme der österreichischen Zeitgeschichte • Nachwuchsforum Institut für Zeitgeschichte Universität Innsbruck Veranstalter: Institut für Zeitgeschichte der Universität Innsbruck http://www.uibk.ac.at/zeitgeschichte/ [email protected] Organisationsteam: o.Univ.-Prof. Dr. Rolf Steininger Univ.-Ass. Mag. Dr. Ingrid Böhler Univ.-Ass. Mag. Dr. Eva Pfanzelter M.A. Univ.-Ass. Mag. Dr. Thomas Spielbüchler Mag. Hüseyin Cicek Kontakt: Institut für Zeitgeschichte, Innrain 52, 6020 Innsbruck Tel.: +43 512 507-4406 Fax: +43 512 507-2889 E-Mail: [email protected] Anmeldung unter: http://www.zeitgeschichtetag2008.at/ Für Technik und Graphik der Homepage danken wir herzlich Hermann Schwärzler und Christoph Praxmarer. Layout Programmheft: Karin Berner Mit Unterstützung von: Land Südtirol Umschlagbild: Warschauer Pakt-Truppen beenden im August 1968 den Prager Frühling (© Franz Goess, ÖNB/Wien). Willkommen Liebe TeilnehmerInnen am 7. Österreichischen Zeitgeschichtetag vom 28. bis 31. Mai 2008 Ein herzliches Willkommen in Innsbruck! Wir danken allen, die diesen Zeitgeschichte- Zum zweiten Mal nach 1993 organisiert das tag durch ihre Unterstützung ermög- Institut für Zeitgeschichte der Universität licht haben, allen voran Bundesminister Innsbruck den Zeitgeschichtetag. Er ist mit Dr. Johannes Hahn, den Landeshauptleuten 47 Panels und zahlreichen anderen Veran- DDr. Herwig van Staa (Tirol), Dr. Luis Durn- staltungen der bislang umfangreichste – walder (Südtirol), Dr. Herbert Sausgruber nicht zuletzt ein Zeichen für die Aktivität (Vorarlberg), der Bürgermeisterin von der österreichischen Kolleginnen und Kol- Innsbruck, Hilde Zach, dem Rektor unserer legen, mit der wir auch im internationalen Universität, o.Univ.-Prof. Dr. Karlheinz Töch- Vergleich sehr gut bestehen können. -

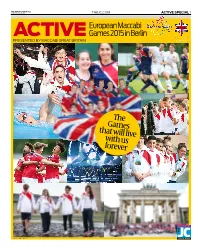

The Games That Will Live with Us Forever

THE JEWISH CHRONICLE 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 THEJC.COM ACTIVE SPECIAL 1 European Maccabi ACTIVE Games 2015 in Berlin PRESENTED BY MACCABI GREAT BRITAIN The Games that will live with us forever MEDIA partner PHOTOS: MARC MORRIS THE JEWISH CHRONICLE THE JEWISH CHRONICLE 2 ACTIVE SPECIAL THEJC.COM 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 THEJC.COM ACTIVE SPECIAL 3 ALL ALL WORDS PHOTOS WELCOME BY DAnnY BY MARC CARO MORRIS Maccabi movement’s ‘miracle’ in Berlin LDN Investments are proud to be associated with Maccabi GB and the success of the European Maccabi Games in Berlin. HIS SUMMER, old; athletes and their families; reuniting THE MACCABI SPIRIT place where they were banished from first night at the GB/USA Gala Dinner, “By SOMETHING hap- existing friendships and creating those Despite the obvious emotion of the participating in sport under Hitler’s winning medals we have not won. By pened which had anew. Friendships that will last a lifetime. Opening Ceremony, the European Mac- reign was a thrill and it gave me an just being here in Berlin we have won.” never occurred But there was also something dif- cabi Games 2015 was one big party, one enormous sense of pride. We will spread the word, keep the before. For the first ferent about these Games – something enormous celebration of life and of Having been there for a couple of days, torch of love, not hate, burning bright. time in history, the that no other EMG has had before it. good triumphing over evil. Many thou- my hate of Berlin turned to wonder. -

Political Languages in the Age of Extremes

00 Pol Lang Prelims. 4/4/11 11:45 Page iii AN OFFPRINT FROM Political Languages in the Age of Extremes EDITED BY WILLIBALD STEINMETZ GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE LONDON 1 00 Pol Lang Prelims. 4/4/11 11:45 Page iv 14 Pol. Lang. ch 14 4/4/11 11:27 Page 351 14 Suppression of the Nazi Past, Coded Languages, and Discourses of Silence : Applying the Discourse-Historical Approach to Post-War Anti-Semitism in Austria RUTH WODAK I Setting the Agenda In this essay I discuss some aspects of the revival/continuance of Austrian anti-Semitism since . First, a short summary of the history of post-war anti-Semitism in Austria is necessary in order to allow a contextualization of specific utterances from the Vienna election campaign of which will be analysed in detail below. Secondly, I will elaborate the Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA) which should allow readers to follow and understand the in-depth discourse analysis of specific utterances by Jörg Haider, the former leader of the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), during the election campaign. Finally, the question of whether we are dealing with ‘new–old’ anti-Semitism in Europe or just ‘more of the same’ will be raised. This topic is constantly I am very grateful to the Leverhulme Trust which awarded me a Leverhulme Visiting Professorship at UEA, Norwich, in the spring term of . This made it possible to elab - orate this essay which is based on previous and ongoing research on anti-Semitic dis - courses. Thus I draw on research published in Ruth Wodak, J. -

Controversies Over Holocaust Memory and Holocaust Revisionism in Poland and Moldova

Kantor Center Position Papers Editor: Mikael Shainkman March 2014 HOLOCAUST MEMORY AND HOLOCAUST DENIAL IN POLAND AND MOLDOVA: A COMPARISON Natalia Sineaeva-Pankowska* Executive Summary After 1989, post-communist countries such as Poland and Moldova have been faced with the challenge of reinventing their national identity and rewriting their master narratives, shifting from a communist one to an ethnic-patriotic one. In this context, the fate of local Jews and the actions of Poles and Moldovans during the Holocaust have repeatedly proven difficult or even impossible to incorporate into the new national narrative. As a result, Holocaust denial in various forms initially gained ground in post-communist countries, since denying the Holocaust, or blaming it on someone else, even on the Jews themselves, was the easiest way to strengthen national identities. In later years, however, Polish and Moldovan paths towards re-definition of self have taken different paths. At least in part, this can be explained as a product of Poland's incorporation in the European unification project, while Moldova remains in limbo, both in terms of identity and politics – between the Soviet Union and Europe, between the past and the future. Introduction This paper focuses on the debate over Holocaust memory and its link to national identity in two post-communist countries, Poland and Moldova, after 1989. Although their historical, political and social contexts and other factors differ, both countries possess a similar, albeit not identical, communist legacy, and both countries had to accept ‘inconvenient’ truths, such as participation of members of one’s own nation in the Holocaust, while building-rebuilding their new post-communist national identities during a period of social and political transformation. -

Between Denial and "Comparative Trivialization": Holocaust Negationism in Post-Communist East Central Europe

Between Denial and "Comparative Trivialization": Holocaust Negationism in Post-Communist East Central Europe Michael Shafir Motto: They used to pour millet on graves or poppy seeds To feed the dead who would come disguised as birds. I put this book here for you, who once lived So that you should visit us no more Czeslaw Milosz Introduction* Holocaust denial in post-Communist East Central Europe is a fact. And, like most facts, its shades are many. Sometimes, denial comes in explicit forms – visible and universally-aggressive. At other times, however, it is implicit rather than explicit, particularistic rather than universal, defensive rather than aggressive. And between these two poles, the spectrum is large enough to allow for a large variety of forms, some of which may escape the eye of all but the most versatile connoisseurs of country-specific history, culture, or immediate political environment. In other words, Holocaust denial in the region ranges from sheer emulation of negationism elsewhere in the world to regional-specific forms of collective defense of national "historic memory" and to merely banal, indeed sometime cynical, attempts at the utilitarian exploitation of an immediate political context.1 The paradox of Holocaust negation in East Central Europe is that, alas, this is neither "good" nor "bad" for the Jews.2 But it is an important part of the * I would like to acknowledge the support of the J. and O. Winter Fund of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York for research conducted in connection with this project. I am indebted to friends and colleagues who read manuscripts of earlier versions and provided comments and corrections. -

2018–2019 Annual Report

18|19 Annual Report Contents 2 62 From the Chairman of the Board Ensemble Connect 4 66 From the Executive and Artistic Director Digital Initiatives 6 68 Board of Trustees Donors 8 96 2018–2019 Concert Season Treasurer’s Review 36 97 Carnegie Hall Citywide Consolidated Balance Sheet 38 98 Map of Carnegie Hall Programs Administrative Staff Photos: Harding by Fadi Kheir, (front cover) 40 101 Weill Music Institute Music Ambassadors Live from Here 56 Front cover photo: Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer, by Stephanie Berger. Stephanie by Chris “Critter” Eldridge, and Chris Thile National Youth Ensembles in Live from Here March 9 Daniel Harding and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra February 14 From the Chairman of the Board Dear Friends, In the 12 months since the last publication of this annual report, we have mourned the passing, but equally importantly, celebrated the lives of six beloved trustees who served Carnegie Hall over the years with the utmost grace, dedication, and It is my great pleasure to share with you Carnegie Hall’s 2018–2019 Annual Report. distinction. Last spring, we lost Charles M. Rosenthal, Senior Managing Director at First Manhattan and a longtime advocate of These pages detail the historic work that has been made possible by your support, Carnegie Hall. Charles was elected to the board in 2012, sharing his considerable financial expertise and bringing a deep love and further emphasize the extraordinary progress made by this institution to of music and an unstinting commitment to helping the aspiring young musicians of Ensemble Connect realize their potential. extend the reach of our artistic, education, and social impact programs far beyond In August 2019, Kenneth J. -

Rome International Conference on the Responsibility of States, Institutions and Individuals in the Fight Against Anti-Semitism in the OSCE Area

Rome International Conference on the Responsibility of States, Institutions and Individuals in the Fight against Anti-Semitism in the OSCE Area Rome, Italy, 29 January 2018 PROGRAMME Monday, 29 January 10.00 - 10.30 Registration of participants and welcome coffee 10.45 - 13.30 Plenary session, International Conference Hall 10.45 - 11.30 Opening remarks: - H.E. Angelino Alfano, Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, OSCE Chairperson-in-Office - H.E. Ambassador Thomas Greminger, OSCE Secretary General - H. E. Ingibjörg Sólrún Gísladóttir, ODIHR Director - Ronald Lauder, President, World Jewish Congress - Moshe Kantor, President, European Jewish Congress - Noemi Di Segni, President, Union of the Italian Jewish Communities 11.30 – 13.00 Interventions by Ministers 13.00 - 13.30 The Meaning of Responsibility: - Rabbi Israel Meir Lau, Chairman of Yad Vashem Council - Daniel S. Mariaschin, CEO B’nai Brith - Prof. Andrea Riccardi, Founder of the Community of Sant’Egidio 13.30 - 14.15 Lunch break - 2 - 14.15 - 16.15 Panel 1, International Conference Hall “Responsibility: the role of law makers and civil servants” Moderator: Maurizio Molinari, Editor in Chief of the daily La Stampa Panel Speakers: - David Harris’s Video Message, CEO American Jewish Committee - Cristina Finch, Head of Department for Tolerance and Non- discrimination, ODHIR - Katharina von Schnurbein, Special Coordinator of EU Commission on Anti-Semitism - Franco Gabrielli, Chief of Italian Police - Ruth Dureghello, President of Rome Jewish Community - Sandro De -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

Manifestations of Antisemitism in the EU 2002 - 2003

Manifestations of Antisemitism in the EU 2002 - 2003 Based on information by the National Focal Points of the RAXEN Information Network Manifestations of Antisemitism in the EU 2002 – 2003 Based on information by the National Focal Points of the EUMC - RAXEN Information Network EUMC - Manifestations of Antisemitism in the EU 2002 - 2003 2 EUMC – Manifestations of Antisemitism in the EU 2002 – 2003 Foreword Following concerns from many quarters over what seemed to be a serious increase in acts of antisemitism in some parts of Europe, especially in March/April 2002, the EUMC asked the 15 National Focal Points of its Racism and Xenophobia Network (RAXEN) to direct a special focus on antisemitism in its data collection activities. This comprehensive report is one of the outcomes of that initiative. It represents the first time in the EU that data on antisemitism has been collected systematically, using common guidelines for each Member State. The national reports delivered by the RAXEN network provide an overview of incidents of antisemitism, the political, academic and media reactions to it, information from public opinion polls and attitude surveys, and examples of good practice to combat antisemitism, from information available in the years 2002 – 2003. On receipt of these national reports, the EUMC then asked an independent scholar, Dr Alexander Pollak, to make an evaluation of the quality and availability of this data on antisemitism in each country, and identify problem areas and gaps. The country-by-country information provided by the 15 National Focal Points, and the analysis by Dr Pollak, form Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 of this report respectively. -

Eva Pfanzelter Sausgruber

Curriculum Vitae Eva Pfanzelter Sausgruber Ass. Prof. Dr. Mag. (M.A.), Institute of Contemporary History, University of Innsbruck Christoph Probst Platz, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria (Updated November 2010) Education 2006 Dr. der Philosophy (Ph.D.) University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria; 1995 Magistra der Philosophie (M.Phil.) University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria; 1994 Master of Arts Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, Illinois, USA; 1993 – 1994 Master Degree Program in History, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, Illinois, USA; 1988 – 1995 BA Degree Program in History and Selected Subjects, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria; 1983 – 1988 Highschool „Raimund von Klebelsberg“, Bozen, Italy; Work experience Since Oct. Assistant Professor, Institute of Contemporary History, University of Innsbruck, 2010 Innsbruck, Austria; 1999 – 2007 Researcher and Lecturer (Universitätsassistentin), Institute of Contemporary History, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria; (maternity leave March 2000 – September 2002 and March 2008 – March 2009); 1997 – 1999 Research Assistant part time (research grant), project „The American Occupation of South Tirol“, Institute of Contemporary History, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria; 1996 – 1999 Research Assistant part time, different research projects (Austria-Israel Studies, South Tirol Documents in the World, Zeitgeschichte Informations-System), Institute of Contemporary History, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria; 1995 – 1996 Programming and marketing, archive software „M-Box“, „daten unlimited“ Software Company, Innsbruck, Austria; 1993 – 1994 Graduate Assistantship, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL, USA; 1990 Assistant, Task Force Pro Libra Ltd., Publishing Company, London, England; Current Major Research Project Holocaust and genocide websites between media discourse, politics of memory and politicking (habilitation/postdoctoral qualification). 1 Publications Scientific degree theses 2005 doctoral dissertation (Ph.D. thesis): Der amerikanische Blick auf Südtirol.