THE TEMPLE of QUETZALCOATL at TEOTIHUACAN Its Possible Ideological Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chichen Itza Coordinates: 20°40ʹ58.44ʺN 88°34ʹ7.14ʺW from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Chichen Itza Coordinates: 20°40ʹ58.44ʺN 88°34ʹ7.14ʺW From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Chichen Itza ( /tʃiːˈtʃɛn iːˈtsɑː/;[1] from Yucatec Pre-Hispanic City of Chichen-Itza* Maya: Chi'ch'èen Ìitsha',[2] "at the mouth of the well UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Itza") is a large pre-Columbian archaeological site built by the Maya civilization located in the northern center of the Yucatán Peninsula, in the Municipality of Tinúm, Yucatán state, present-day Mexico. Chichen Itza was a major focal point in the northern Maya lowlands from the Late Classic through the Terminal Classic and into the early portion of the Early Postclassic period. The site exhibits a multitude of architectural styles, from what is called “In the Mexican Origin” and reminiscent of styles seen in central Mexico to the Puuc style found among the Country Mexico Puuc Maya of the northern lowlands. The presence of Type Cultural central Mexican styles was once thought to have been Criteria i, ii, iii representative of direct migration or even conquest from central Mexico, but most contemporary Reference 483 (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/483) interpretations view the presence of these non-Maya Region** Latin America and the Caribbean styles more as the result of cultural diffusion. Inscription history The ruins of Chichen Itza are federal property, and the Inscription 1988 (12th Session) site’s stewardship is maintained by Mexico’s Instituto * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. Nacional de Antropología e Historia (National (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list) Institute of Anthropology and History, INAH). The ** Region as classified by UNESCO. -

Aztec Mythology

Aztec Mythology One of the main things that must be appreciated about Aztec mythology is that it has both similarities and differences to European polytheistic religions. The idea of what a god was, and how they acted, was not the same between the two cultures. Along with all other native American religions, the Aztec faith developed from the Shamanism brought by the first migrants over the Bering Strait, and developed independently of influences from across the Atlantic (and Pacific). The concept of dualism is one that students of Chinese religions should be aware of; the idea of balance was primary in this belief system. Gods were not entirely good or entirely bad, being complex characters with many different aspects and their own desires and motivations. This is highlighted by the relation between Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca. When the Spanish arrived with their European sensibilities, they were quick to name one good and one evil, identifying Quetzalcoatl with Christ and Tezcatlipoca with Satan during their attempts to integrate the Nahua peoples into Christianity. But to the Aztecs neither god would have been “better” than the other; they are just different and opposing sides of the same duality. Indeed, their identities are rather nebulous, with Quetzalcoatl often being referred to as “White Tezcatlipoca” and Tezcatlipoca as “Black Quetzalcoatl”. The Mexica, as is explained in the history section, came from North of Mexico in a location they named “Aztlan” (from which Europeans developed the term Aztec). During their migration south they were exposed to and assimilated elements of several native religions, including those of the Toltecs, Mayans, and Zapotecs. -

God of the Month: Tlaloc

God of the Month: Tlaloc Tlaloc, lord of celestial waters, lightning flashes and hail, patron of land workers, was one of the oldest and most important deities in the Aztec pantheon. Archaeological evidence indicates that he was worshipped in Mesoamerica before the Aztecs even settled in Mexico's central highlands in the 13th century AD. Ceramics depicting a water deity accompanied by serpentine lightning bolts date back to the 1st Tlaloc shown with a jaguar helm. Codex Vaticanus B. century BC in Veracruz, Eastern Mexico. Tlaloc's antiquity as a god is only rivalled by Xiuhtecuhtli the fire lord (also Huehueteotl, old god) whose appearance in history is marked around the last few centuries BC. Tlaloc's main purpose was to send rain to nourish the growing corn and crops. He was able to delay rains or send forth harmful hail, therefore it was very important for the Aztecs to pray to him, and secure his favour for the following agricultural cycle. Read on and discover how crying children, lepers, drowned people, moun- taintops and caves were all important parts of the symbolism surrounding this powerful ancient god... Starting at the very beginning: Tlaloc in Watery Deaths Tamoanchan. Right at the beginning of the world, before the gods were sent down to live on Earth as mortal beings, they Aztecs who died from one of a list of the fol- lived in Tamoanchan, a paradise created by the divine lowing illnesses or incidents were thought to Tlaloc vase. being Ometeotl for his deity children. be sent to the 'earthly paradise' of Tlalocan. -

OCTLI'- See Pulque. OFFERINGS

OFFERINGS 403 OCTLI'- See Pulque. vidual was buried together with the objects necessary for living in the afterlife; alternatively, it could be the vestiges of a dedicatory rite in which a new building was given OFFERINGS. Buried offerings are the material ex- essence by interring a sacrificial victim with various ce- pressions of rites of sacrifice, or oblation. They are the ramic vessels. tangible result of individual or collective acts of a sym- As a consequence of two centuries of archaeological in- bolic character that are repeated according to invariable vestigations throughout Mesoamerica, we now have an rules and that achieve effects that are, at least in part, of impressive corpus of buried offerings. This rich assort- an extra-empirical nature. In specific terms, offerings are ment often permits us to recognize the traditions of obla- donations made by the faithful with the purpose of estab- tion practiced in a city, a group of cities, a region, or an lishing a cornmunication and exchange with the super- area, in addition to the principal transformations that oc- natural. In this reciprocal process, the believer gives curred through four millennia of Mesoamerican history. something to adivine being in the hope of currying its The oldest buried offerings date to the Early Formative favor and obtaining a greater benefit in return. With of- period (2500-1200 BCE) and generally consist of anthro- ferings and sacrifices, one propitiates or "pays for" all pomorphic figurines and ceramic vessels deposited in the types of divine favors, including rain, plentiful harvests, construction fill of the village dwellings. -

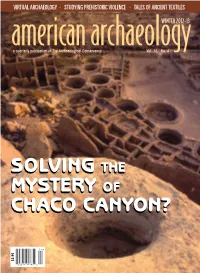

Solving the Mystery of Chaco Canyon?

VIRTUALBANNER ARCHAEOLOGY BANNER • BANNER STUDYING • BANNER PREHISTORIC BANNER VIOLENCE BANNER • T •ALE BANNERS OF A NCIENT BANNER TEXTILE S american archaeologyWINTER 2012-13 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 SOLVINGSOLVING THETHE MYMYSSTERYTERY OFOF CHACHACCOO CANYONCANYON?? $3.95 $3.95 WINTER 2012-13 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 COVER FEATURE 26 CHACO, THROUGH A DIFFERENT LENS BY MIKE TONER Southwest scholar Steve Lekson has taken an unconventional approach to solving the mystery of Chaco Canyon. 12 VIRTUALLY RECREATING THE PAST BY JULIAN SMITH Virtual archaeology has remarkable potential, but it also has some issues to resolve. 19 A ROAD TO THE PAST BY ALISON MCCOOK A dig resulting from a highway project is yielding insights into Delaware’s colonial history. 33 THE TALES OF ANCIENT TEXTILES BY PAULA NEELY Fabric artifacts are providing a relatively new line of evidence for archaeologists. 39 UNDERSTANDING PREHISTORIC VIOLENCE BY DAN FERBER Bioarchaeologists have gone beyond studying the manifestations of ancient violence to examining CHAZ EVANS the conditions that caused it. 26 45 new acquisition A TRAIL TO PREHISTORY The Conservancy saves a trailhead leading to an important Sinagua settlement. 46 new acquisition NORTHERNMOST CHACO CANYON OUTLIER TO BE PRESERVED Carhart Pueblo holds clues to the broader Chaco regional system. 48 point acquisition A GLIMPSE OF A MAJOR TRANSITION D LEVY R Herd Village could reveal information about the change from the Basketmaker III to the Pueblo I phase. RICHA 12 2 Lay of the Land 50 Field Notes 52 RevieWS 54 Expeditions 3 Letters 5 Events COVER: Pueblo Bonito is one of the great houses at Chaco Canyon. -

Ancient Civilisation’ Through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures

Structuring The Notion of ‘Ancient Civilisation’ through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez Institute of Archaeology U C L Thesis forPh.D. in Archaeology 2011 1 I, Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis Signature 2 This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents Emma and Andrés, Dolores and Concepción: their love has borne fruit Esta tesis está dedicada a mis abuelos Emma y Andrés, Dolores y Concepción: su amor ha dado fruto Al ‘Pipila’ porque él supo lo que es cargar lápidas To ‘Pipila’ since he knew the burden of carrying big stones 3 ABSTRACT This research focuses on studying the representation of the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ in displays produced in Britain and the United States during the early to mid-nineteenth century, a period that some consider the beginning of scientific archaeology. The study is based on new theoretical ground, the Semantic Structural Model, which proposes that the function of an exhibition is the loading and unloading of an intelligible ‘system of ideas’, a process that allows the transaction of complex notions between the producer of the exhibit and its viewers. Based on semantic research, this investigation seeks to evaluate how the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ was structured, articulated and transmitted through exhibition practices. To fulfil this aim, I first examine the way in which ideas about ‘ancientness’ and ‘cultural complexity’ were formulated in Western literature before the last third of the 1800s. -

The Barroque Paradise of Santa María Tonantzintla (Part II1)

14 ETHNOLOGIA ACTUALIS Vol. 16, No. 2/2016 JULIO GLOCKNER The Barroque Paradise of Santa María Tonantzitla II The Barroque Paradise of Santa María Tonantzintla (Part II1) JULIO GLOCKNER Institute of Social Sciences and Humanities, Meritorious Autonomous University of Puebla, Puebla [email protected] ABSTRACT The baroque church of Santa María Tonantzintla is located in the Valley of Cholula in the Central Mexican Plateau and it was built during 16th-19th century. Its interior decoration shows an interesting symbolic fusion of Christian elements with Mesoamerican religious aspects of Nahua origin. Scholars of Mexican colonial art interpreted the Catholic iconography of Santa María Tonantzintla church as the Assumption of the Virgin Mary up to the celestial kingdom and her coronation by the holy Trinity. One of those scholars, Francisco de la Maza, proposed the idea that apart from that, the ornaments of the church evoke Tlalocan, paradise of the ancient deity of rain known as Tlaloc. Following this interpretation this study explores the relation between the Virgin Mary and the ancient Nahua deity of Earth and fertility called Tonatzin in order to show the profound syncretic bonds which exist between Christian and Mesoamerican traditions. KEY WORDS: syncretism, altepetl, Tlalocan, Tamoanchan, Ometeotl, Nahua culture, Tonantzintla 1 This text is a continuation of the article published in previous volume. In. Ethnologia actualis. Vol. 16, No. 1/2016, pp. 8-29. DOI: 10.1515/eas-2017-0002 © University of SS. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava. All rights reserved. 15 ETHNOLOGIA ACTUALIS Vol. 16, No. 2/2016 JULIO GLOCKNER The Barroque Paradise of Santa María Tonantzitla II The myth of the origin of corn From the rest of the plants cultivated traditionally in the area, corn stands out, a plant divinized during the pre-Hispanic era with the name Centeotl. -

Encounter with the Plumed Serpent

Maarten Jansen and Gabina Aurora Pérez Jiménez ENCOUNTENCOUNTEERR withwith thethe Drama and Power in the Heart of Mesoamerica Preface Encounter WITH THE plumed serpent i Mesoamerican Worlds From the Olmecs to the Danzantes GENERAL EDITORS: DAVÍD CARRASCO AND EDUARDO MATOS MOCTEZUMA The Apotheosis of Janaab’ Pakal: Science, History, and Religion at Classic Maya Palenque, GERARDO ALDANA Commoner Ritual and Ideology in Ancient Mesoamerica, NANCY GONLIN AND JON C. LOHSE, EDITORS Eating Landscape: Aztec and European Occupation of Tlalocan, PHILIP P. ARNOLD Empires of Time: Calendars, Clocks, and Cultures, Revised Edition, ANTHONY AVENI Encounter with the Plumed Serpent: Drama and Power in the Heart of Mesoamerica, MAARTEN JANSEN AND GABINA AURORA PÉREZ JIMÉNEZ In the Realm of Nachan Kan: Postclassic Maya Archaeology at Laguna de On, Belize, MARILYN A. MASSON Life and Death in the Templo Mayor, EDUARDO MATOS MOCTEZUMA The Madrid Codex: New Approaches to Understanding an Ancient Maya Manuscript, GABRIELLE VAIL AND ANTHONY AVENI, EDITORS Mesoamerican Ritual Economy: Archaeological and Ethnological Perspectives, E. CHRISTIAN WELLS AND KARLA L. DAVIS-SALAZAR, EDITORS Mesoamerica’s Classic Heritage: Teotihuacan to the Aztecs, DAVÍD CARRASCO, LINDSAY JONES, AND SCOTT SESSIONS Mockeries and Metamorphoses of an Aztec God: Tezcatlipoca, “Lord of the Smoking Mirror,” GUILHEM OLIVIER, TRANSLATED BY MICHEL BESSON Rabinal Achi: A Fifteenth-Century Maya Dynastic Drama, ALAIN BRETON, EDITOR; TRANSLATED BY TERESA LAVENDER FAGAN AND ROBERT SCHNEIDER Representing Aztec Ritual: Performance, Text, and Image in the Work of Sahagún, ELOISE QUIÑONES KEBER, EDITOR The Social Experience of Childhood in Mesoamerica, TRACI ARDREN AND SCOTT R. HUTSON, EDITORS Stone Houses and Earth Lords: Maya Religion in the Cave Context, KEITH M. -

Changes and Continuities in Ritual Practice at Chechem Ha Cave, Belize

FAMSI © 2010: Esperanza Elizabeth Jiménez García Sculptural-Iconographic Catalogue of Tula, Hidalgo: The Stone Figures Research Year: 2007 Culture : Toltec Chronology : Post-Classic Location : México, Hidalgo Site : Tula Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Introduction The Tula Archaeological Zone The Settlement Tula's Sculpture 1 The Conformation of the Catalogue Recording the Materials The Formal-architectural Classification Architectural Elements The Catalogue Proposed Chronological Periods Period 1 Period 2 Period 3 Acknowledgments List of Figures Sources Cited Abstract The goal of this study was to make a catalogue of sculptures integrated by archaeological materials made of stone from the Prehispanic city of Tula, in the state of Hidalgo, Mexico. A total of 971 pieces or fragments were recorded, as well as 17 panels or sections pertaining to projecting panels and banquettes found in situ . Because of the great amount of pieces we found, as well as the variety of designs we detected both in whole pieces and in fragments, it was necessary to perform their recording and classification as well. As a result of this study we were able to define the sculptural and iconographic characteristics of this metropolis, which had a great political, religious, and ideological importance throughout Mesoamerica. The study of these materials allowed us to have a better knowledge of the figures represented, therefore in this study we offer a tentative periodic scheme which may reflect several historical stages through which the city's sculptural and architectural development went between AD 700-1200. Resumen El objetivo de este trabajo, fue la realización de un catálogo escultórico integrado por materiales arqueológicos de piedra que procedieran de la ciudad prehispánica de Tula, en el estado de Hidalgo, México. -

The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the Cult of Sacred War at Teotihuacan

The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the cult of sacred war at Teotihuacan KARLA. TAUBE The Temple of Quetzalcoatl at Teotihuacan has been warrior elements found in the Maya region also appear the source of startling archaeological discoveries since among the Classic Zapotee of Oaxaca. Finally, using the early portion of this century. Beginning in 1918, ethnohistoric data pertaining to the Aztec, Iwill discuss excavations by Manuel Gamio revealed an elaborate the possible ethos surrounding the Teotihuacan cult and beautifully preserved facade underlying later of war. construction. Although excavations were performed intermittently during the subsequent decades, some of The Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the Tezcacoac the most important discoveries have occurred during the last several years. Recent investigations have Located in the rear center of the great Ciudadela revealed mass dedicatory burials in the foundations of compound, the Temple of Quetzalcoatl is one of the the Temple of Quetzalcoatl (Sugiyama 1989; Cabrera, largest pyramidal structures at Teotihuacan. In volume, Sugiyama, and Cowgill 1988); at the time of this it ranks only third after the Pyramid of the Moon and writing, more than eighty individuals have been the Pyramid of the Sun (Cowgill 1983: 322). As a result discovered interred in the foundations of the pyramid. of the Teotihuacan Mapping Project, it is now known Sugiyama (1989) persuasively argues that many of the that the Temple of Quetzalcoatl and the enclosing individuals appear to be either warriors or dressed in Ciudadela are located in the center of the ancient city the office of war. (Mill?n 1976: 236). The Ciudadela iswidely considered The archaeological investigations by Cabrera, to have been the seat of Teotihuacan rulership, and Sugiyama, and Cowgill are ongoing, and to comment held the palaces of the principal Teotihuacan lords extensively on the implications of their work would be (e.g., Armillas 1964: 307; Mill?n 1973: 55; Coe 1981: both premature and presumptuous. -

Breaking the Maya Code : Michael D. Coe Interview (Night Fire Films)

BREAKING THE MAYA CODE Transcript of filmed interview Complete interview transcripts at www.nightfirefilms.org MICHAEL D. COE Interviewed April 6 and 7, 2005 at his home in New Haven, Connecticut In the 1950s archaeologist Michael Coe was one of the pioneering investigators of the Olmec Civilization. He later made major contributions to Maya epigraphy and iconography. In more recent years he has studied the Khmer civilization of Cambodia. He is the Charles J. MacCurdy Professor of Anthropology, Emeritus at Yale University, and Curator Emeritus of the Anthropology collection of Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. He is the author of Breaking the Maya Code and numerous other books including The Maya Scribe and His World, The Maya and Angkor and the Khmer Civilization. In this interview he discusses: The nature of writing systems The origin of Maya writing The role of writing and scribes in Maya culture The status of Maya writing at the time of the Spanish conquest The impact for good and ill of Bishop Landa The persistence of scribal activity in the books of Chilam Balam and the Caste War Letters Early exploration in the Maya region and early publication of Maya texts The work of Constantine Rafinesque, Stephens and Catherwood, de Bourbourg, Ernst Förstemann, and Alfred Maudslay The Maya Corpus Project Cyrus Thomas Sylvanus Morley and the Carnegie Projects Eric Thompson Hermann Beyer Yuri Knorosov Tania Proskouriakoff His own early involvement with study of the Maya and the Olmec His personal relationship with Yuri -

Aztec Festivals of the Rain Gods

Michael Graulich Aztec Festivals of the Rain Gods Aunque contiene ritos indiscutiblemente agrícolas, el antiguo calendario festivo de veintenas (o 'meses') de la época azteca resulta totalmente desplazado en cuanto a las temporadas, puesto que carece de intercalados que adaptan el año solar de 365 días a la duración efectiva del año tropical. Creo haber demostrado en diversas pu- blicaciones que las fiestas pueden ser interpretadas en rigor sólo en relación con su posición original, no corrida aún. El presente trabajo muestra cómo los rituales y la re- partición absolutamente regular y lógica de las vein- tenas, dedicadas esencialmente a las deidades de la llu- via - tres en la temporada de lluvias y una en la tempo- rada de sequía - confirman el fenómeno del desplaza- miento. The Central Mexican festivals of the solar year are described with consi- derable detail in XVIth century sources and some of them have even been stu- died by modern investigators (Paso y Troncoso 1898; Seler 1899; Margain Araujo 1945; Acosta Saignes 1950; Nowotny 1968; Broda 1970, 1971; Kirchhoff 1971). New interpretations are nevertheless still possible, especially since the festivals have never been studied as a whole, with reference to the myths they reenacted, and therefore, could not be put in a proper perspective. Until now, the rituals of the 18 veintenas {twenty-day 'months') have always been interpreted according to their position in the solar year at the time they were first described to the Spaniards. Such festivals with agricultural rites have been interpreted, for example, as sowing or harvest festivals on the sole ground that in the 16th century they more or less coincided with those seasonal events.