Chemical Storage Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allyson M. Buytendyk

DISCOVERING THE ELECTRONIC PROPERTIES OF METAL HYDRIDES, METAL OXIDES AND ORGANIC MOLECULES USING ANION PHOTOELECTRON SPECTROSCOPY by Allyson M. Buytendyk A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland September, 2015 © 2015 Allyson M. Buytendyk All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Negatively charged molecular ions were studied in the gas phase using anion photoelectron spectroscopy. By coupling theory with the experimentally measured electronic structure, the geometries of the neutral and anion complexes could be predicted. The experiments were conducted using a one-of-a-kind time- of-flight mass spectrometer coupled with a pulsed negative ion photoelectron spectrometer. The molecules studied include metal oxides, metal hydrides, aromatic heterocylic organic compounds, and proton-coupled organic acids. Metal oxides serve as catalysts in reactions from many scientific fields and understanding the catalysis process at the molecular level could help improve reaction efficiencies - - (Chapter 1). The experimental investigation of the super-alkali anions, Li3O and Na3O , revealed both photodetachment and photoionization occur due to the low ionization potential of both neutral molecules. Additionally, HfO- and ZrO- were studied, and although both Hf and Zr have very similar atomic properties, their oxides differ greatly where ZrO- has a much lower electron affinity than HfO-. In the pursuit of using hydrogen as an environmentally friendly fuel alternative, a practical method for storing hydrogen is necessary and metal hydrides are thought to be the answer (Chapter 2). Studies yielding structural and electronic information about the hydrogen - - bonding/interacting in the complex, such as in MgH and AlH4 , are vital to constructing a practical hydrogen storage device. -

Acidity, Basicity, and Pka 8 Connections

Acidity, basicity, and pKa 8 Connections Building on: Arriving at: Looking forward to: • Conjugation and molecular stability • Why some molecules are acidic and • Acid and base catalysis in carbonyl ch7 others basic reactions ch12 & ch14 • Curly arrows represent delocalization • Why some acids are strong and others • The role of catalysts in organic and mechanisms ch5 weak mechanisms ch13 • How orbitals overlap to form • Why some bases are strong and others • Making reactions selective using conjugated systems ch4 weak acids and bases ch24 • Estimating acidity and basicity using pH and pKa • Structure and equilibria in proton- transfer reactions • Which protons in more complex molecules are more acidic • Which lone pairs in more complex molecules are more basic • Quantitative acid/base ideas affecting reactions and solubility • Effects of quantitative acid/base ideas on medicine design Note from the authors to all readers This chapter contains physical data and mathematical material that some readers may find daunting. Organic chemistry students come from many different backgrounds since organic chemistry occu- pies a middle ground between the physical and the biological sciences. We hope that those from a more physical background will enjoy the material as it is. If you are one of those, you should work your way through the entire chapter. If you come from a more biological background, especially if you have done little maths at school, you may lose the essence of the chapter in a struggle to under- stand the equations. We have therefore picked out the more mathematical parts in boxes and you should abandon these parts if you find them too alien. -

The Strongest Acid Christopher A

Chemistry in New Zealand October 2011 The Strongest Acid Christopher A. Reed Department of Chemistry, University of California, Riverside, California 92521, USA Article (e-mail: [email protected]) About the Author Chris Reed was born a kiwi to English parents in Auckland in 1947. He attended Dilworth School from 1956 to 1964 where his interest in chemistry was un- doubtedly stimulated by being entrusted with a key to the high school chemical stockroom. Nighttime experiments with white phosphorus led to the Headmaster administering six of the best. He obtained his BSc (1967), MSc (1st Class Hons., 1968) and PhD (1971) from The University of Auckland, doing thesis research on iridium organotransition metal chemistry with Professor Warren R. Roper FRS. This was followed by two years of postdoctoral study at Stanford Univer- sity with Professor James P. Collman working on picket fence porphyrin models for haemoglobin. In 1973 he joined the faculty of the University of Southern California, becoming Professor in 1979. After 25 years at USC, he moved to his present position of Distinguished Professor of Chemistry at UC-Riverside to build the Centre for s and p Block Chemistry. His present research interests focus on weakly coordinating anions, weakly coordinated ligands, acids, si- lylium ion chemistry, cationic catalysis and reactive cations across the periodic table. His earlier work included extensive studies in metalloporphyrin chemistry, models for dioxygen-binding copper proteins, spin-spin coupling phenomena including paramagnetic metal to ligand radical coupling, a Magnetochemi- cal alternative to the Spectrochemical Series, fullerene redox chemistry, fullerene-porphyrin supramolecular chemistry and metal-organic framework solids (MOFs). -

Determination of Formic Acid in Acetic Acid for Industrial Use by Agilent 7820A GC

Determination of Formic Acid in Acetic Acid for Industrial Use by Agilent 7820A GC Application Brief Wenmin Liu, Chunxiao Wang HPI With rising prices of crude oil and a future shortage of oil and gas resources, people Highlights are relying on the development of the coal chemical industry. • The Agilent 7820A GC coupled with Acetic acid is an important intermediate in coal chemical synthesis. It is used in the a µTCD provides a simple method production of polyethylene, cellulose acetate, and polyvinyl, as well as synthetic for analysis of formic acid in acetic fibres and fabrics. The production of acetic acid will remain high over the next three acid. years. In China, it is estimated that the production capacity of alcohol-to-acetic acid would be 730,000 tons per year in 2010. • ALS and EPC ensure good repeata- biltiy and ease of use which makes The purity of acetic acid determinates the quality of the final synthetic products. the 7820GC appropriate for routine Formic acid is one of the main impurities in acetic acid. Many analytical methods for analysis in QA/QC labs. the analysis of formic acid in acetic acid have been developed using gas chromatog- • Using a capillary column as the ana- raphy. For example, in the GB/T 1628.5-2000 method, packed column and manual lytical column ensures better sepa- sample injection is used with poor separation and repeatability which impacts the ration of formic acid in acetic acid quantification of formic acid. compared to the China GB method. In this application brief, a new analytical method was developed on a new Agilent GC platform, the Agilent 7820A GC System. -

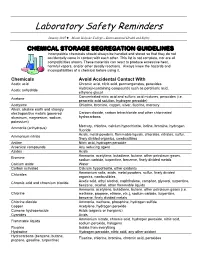

CHEMICAL STORAGE SEGREGATION GUIDELINES Incompatible Chemicals Should Always Be Handled and Stored So That They Do Not Accidentally Come in Contact with Each Other

Laboratory Safety Reminders January 2007 ♦ Mount Holyoke College – Environmental Health and Safety CHEMICAL STORAGE SEGREGATION GUIDELINES Incompatible chemicals should always be handled and stored so that they do not accidentally come in contact with each other. This list is not complete, nor are all compatibilities shown. These materials can react to produce excessive heat, harmful vapors, and/or other deadly reactions. Always know the hazards and incompatibilities of a chemical before using it. Chemicals Avoid Accidental Contact With Acetic acid Chromic acid, nitric acid, permanganates, peroxides Hydroxyl-containing compounds such as perchloric acid, Acetic anhydride ethylene glycol Concentrated nitric acid and sulfuric acid mixtures, peroxides (i.e. Acetone peracetic acid solution, hydrogen peroxide) Acetylene Chlorine, bromine, copper, silver, fluorine, mercury Alkali, alkaline earth and strongly electropositive metals (powered Carbon dioxide, carbon tetrachloride and other chlorinated aluminum, magnesium, sodium, hydrocarbons potassium) Mercury, chlorine, calcium hypochlorite, iodine, bromine, hydrogen Ammonia (anhydrous) fluoride Acids, metal powders, flammable liquids, chlorates, nitrates, sulfur, Ammonium nitrate finely divided organics, combustibles Aniline Nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide Arsenical compounds Any reducing agent Azides Acids Ammonia, acetylene, butadiene, butane, other petroleum gases, Bromine sodium carbide, turpentine, benzene, finely divided metals Calcium oxide Water Carbon activated Calcium hypochlorite, other -

APPENDIX G Acid Dissociation Constants

harxxxxx_App-G.qxd 3/8/10 1:34 PM Page AP11 APPENDIX G Acid Dissociation Constants § ϭ 0.1 M 0 ؍ (Ionic strength ( † ‡ † Name Structure* pKa Ka pKa ϫ Ϫ5 Acetic acid CH3CO2H 4.756 1.75 10 4.56 (ethanoic acid) N ϩ H3 ϫ Ϫ3 Alanine CHCH3 2.344 (CO2H) 4.53 10 2.33 ϫ Ϫ10 9.868 (NH3) 1.36 10 9.71 CO2H ϩ Ϫ5 Aminobenzene NH3 4.601 2.51 ϫ 10 4.64 (aniline) ϪO SNϩ Ϫ4 4-Aminobenzenesulfonic acid 3 H3 3.232 5.86 ϫ 10 3.01 (sulfanilic acid) ϩ NH3 ϫ Ϫ3 2-Aminobenzoic acid 2.08 (CO2H) 8.3 10 2.01 ϫ Ϫ5 (anthranilic acid) 4.96 (NH3) 1.10 10 4.78 CO2H ϩ 2-Aminoethanethiol HSCH2CH2NH3 —— 8.21 (SH) (2-mercaptoethylamine) —— 10.73 (NH3) ϩ ϫ Ϫ10 2-Aminoethanol HOCH2CH2NH3 9.498 3.18 10 9.52 (ethanolamine) O H ϫ Ϫ5 4.70 (NH3) (20°) 2.0 10 4.74 2-Aminophenol Ϫ 9.97 (OH) (20°) 1.05 ϫ 10 10 9.87 ϩ NH3 ϩ ϫ Ϫ10 Ammonia NH4 9.245 5.69 10 9.26 N ϩ H3 N ϩ H2 ϫ Ϫ2 1.823 (CO2H) 1.50 10 2.03 CHCH CH CH NHC ϫ Ϫ9 Arginine 2 2 2 8.991 (NH3) 1.02 10 9.00 NH —— (NH2) —— (12.1) CO2H 2 O Ϫ 2.24 5.8 ϫ 10 3 2.15 Ϫ Arsenic acid HO As OH 6.96 1.10 ϫ 10 7 6.65 Ϫ (hydrogen arsenate) (11.50) 3.2 ϫ 10 12 (11.18) OH ϫ Ϫ10 Arsenious acid As(OH)3 9.29 5.1 10 9.14 (hydrogen arsenite) N ϩ O H3 Asparagine CHCH2CNH2 —— —— 2.16 (CO2H) —— —— 8.73 (NH3) CO2H *Each acid is written in its protonated form. -

United States Patent Office Patented Sept

/ w 3,466,192 United States Patent Office Patented Sept. 9, 1969 1. 2 Typical examples of aqueous oxidizing acid system 3,466,192 CORROSION PREVENTION PROCESS which contain an agent from the class consisting of nitrate George S. Gardner, Elkins Park, Pa., assignor to Amchem ion, ferric ion and hydrogen peroxide, and which are - Products, Inc., Ambler, Pa., a corporation of Delaware suitable for use in accordance with the process of this No Drawing. Filed Jan. 23, 1967, Ser. No. 610,788 invention include: Int, Cl, B08b. 17/00 Nitric acid. - ". U.S. C. 134-3 4 Claims Nitric acid-hydrochloric acid. itric acid--sulfuric acid. Nitric acid, sulfuric acid--ferric sulfate. ABSTRACT OF THE DISCLOSURE 10 Nitric acid--hydrofluoric acid. Oxidizing acid attack on basis metal surfaces is re Hydrochloric acid--ferric chloride. duced by use of an oxidizing acid solution containing Hydrochloric acid, ferric chloride--citric acid. nitrate, ferric ion or hydrogen peroxide along with solu Sulfuric acid--ferric sulfate. ble methylol thiourea compounds in the acid solution. Acetic acid--ferric nitrate. Copper ion is added to enhance corrosion prevention by 15 Glycolic and formic acids--ferric nitrate. the acid solutions. Hydrogen peroxide and hydrofluoric acid. Hydrogen peroxide, hydrochloric acid and acetic or nitric acids. The present invention relates to a method of inhibiting the corrosion of metal surfaces and more particularly is 20 The concentration of the respective components in each concerned with the utilization of inhibited oxidizing acid of these examples of oxidizing acid systems will vary systems for treating metal surfaces. depending upon the type of metal being treated and the It is known in the art that oxidizing acid systems, temperature of treatment as is well known to those skilled while capable of producing the desired treatment of metal in the art of pickling and cleaning of metal surfaces. -

140. Sulphuric, Hydrochloric, Nitric and Phosphoric Acids

nr 2009;43(7) The Nordic Expert Group for Criteria Documentation of Health Risks from Chemicals 140. Sulphuric, hydrochloric, nitric and phosphoric acids Marianne van der Hagen Jill Järnberg arbete och hälsa | vetenskaplig skriftserie isbn 978-91-85971-14-5 issn 0346-7821 Arbete och Hälsa Arbete och Hälsa (Work and Health) is a scientific report series published by Occupational and Enviromental Medicine at Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg. The series publishes scientific original work, review articles, criteria documents and dissertations. All articles are peer-reviewed. Arbete och Hälsa has a broad target group and welcomes articles in different areas. Instructions and templates for manuscript editing are available at http://www.amm.se/aoh Summaries in Swedish and English as well as the complete original texts from 1997 are also available online. Arbete och Hälsa Editorial Board: Editor-in-chief: Kjell Torén Tor Aasen, Bergen Kristina Alexanderson, Stockholm Co-editors: Maria Albin, Ewa Wigaeus Berit Bakke, Oslo Tornqvist, Marianne Törner, Wijnand Lars Barregård, Göteborg Eduard, Lotta Dellve och Roger Persson Jens Peter Bonde, Köpenhamn Managing editor: Cina Holmer Jörgen Eklund, Linköping Mats Eklöf, Göteborg © University of Gothenburg & authors 2009 Mats Hagberg, Göteborg Kari Heldal, Oslo Arbete och Hälsa, University of Gothenburg Kristina Jakobsson, Lund SE 405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden Malin Josephson, Uppsala Bengt Järvholm, Umeå ISBN 978-91-85971-14-5 Anette Kærgaard, Herning ISSN 0346–7821 Ann Kryger, Köpenhamn http://www.amm.se/aoh -

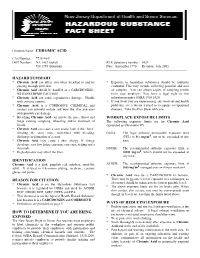

Hazard Summary Identification Reason For

Common Name: CHROMIC ACID CAS Number: 7738-94-5 DOT Number: NA 1463 (Solid) RTK Substance number: 0429 UN 1755 (Solution) Date: September 1996 Revision: July 2002 ------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------------- HAZARD SUMMARY * Chromic Acid can affect you when breathed in and by * Exposure to hazardous substances should be routinely passing through your skin. evaluated. This may include collecting personal and area * Chromic Acid should be handled as a CARCINOGEN-- air samples. You can obtain copies of sampling results WITH EXTREME CAUTION. from your employer. You have a legal right to this * Chromic Acid can cause reproductive damage. Handle information under OSHA 1910.1020. with extreme caution. * If you think you are experiencing any work-related health * Chromic Acid is a CORROSIVE CHEMICAL and problems, see a doctor trained to recognize occupational contact can severely irritate and burn the skin and eyes diseases. Take this Fact Sheet with you. with possible eye damage. * Breathing Chromic Acid can irritate the nose, throat and WORKPLACE EXPOSURE LIMITS lungs causing coughing, wheezing and/or shortness of The following exposure limits are for Chromic Acid breath. (measured as Chromium VI): * Chromic Acid can cause a sore and/or hole in the “bone” dividing the inner nose, sometimes with bleeding, OSHA: The legal airborne permissible exposure limit discharge or formation of a crust. (PEL) is 0.1 mg/m3, not to be exceeded at any * Chromic Acid may cause a skin allergy. If allergy time. develops, very low future exposure can cause itching and a skin rash. NIOSH: The recommended airborne exposure limit is * High exposure may affect the liver. -

Conductivity and Density of Chromic Acid Solutions

; RP198 CONDUCTIVITY AND DENSITY OF CHROMIC ACID SOLU- TIONS By H. R. Moore and W. Blum ABSTRACT The conductivity and density of chromic acid solutions were determined (<*r concentrations to molar up 10 (1,000 g/1 of Cr03 ). The density is practically a linear function of concentration. The conductivity increases to a maximum at about 5 molar and then decreases. CONTENTS Page I. Introduction 255 II. Preparation of solutions 256 1. Purification of chromic acid 256 2. Methods of analysis 257 (a) Preparation of samples 257 (6) Insoluble 257 (c) Sulphate 258 (d) Alkali salts 258 (e) Chromic acid 258 (/) Trivalent chromium 258 (1) Differential titration 258 (2) Direct precipitation 259 III. Conductivity measurements 259 1. Apparatus and method 259 2. Determination of cell constants 260 IV. Density measurements 260 V. Results obtained 261 VI. Conclusions 263 I. INTRODUCTION This study is a step in an investigation of the theory of chromium plating. The solutions used in this process have chromic acid as their principal constituent. In addition, they contain some other anion, such as the sulphate ion, which is introduced as sulphuric acid or as a sulphate. During operation there is always formed in the bath some trivalent chromium, commonly supposed to exist as "chromium chromates" of undefined composition. The ultimate purpose of this research is to determine the form and function of the sulphate and trivalent chromium in such solutions. The effects of these constituents upon the density and conductivity of chromic acid will they throw light on this problem. ; be measured to see whether First, however, it was necessary to determine the density and con- ductivity of pure chromic-acid solutions to serve as a basis of refer- ence. -

Organic Functional Group Analysis

Experiment 1 1 Laboratory Experiments for GOB Chemistry ___________________________________________________________________________________________ I ORGANIC FUNCTIONAL GROUP ANALYSIS I. OBJECTIVES AND BACKGROUND This experiment will introduce you to some of the more common functional groups of organic chemistry. The functional group is that portion of the molecule that undergoes a structural change during a chemical reaction. The functional groups that will be studied in this experiment are carboxylic acid, amines aldehyde, ketone, alcohols and alkenes. You will learn chemical tests that will allow you to distinguish one functional group from another. You will use the chemical tests to identify the functionality of an unknown organic compound. In addition, you will use a water solubility test to determine whether your organic compound is of high or low formula weight. The chemical tests you will perform make up a sequence of experiments designed to determine the absence of or suggest the presence of particular functional groups. The complete sequence is shown in the flow diagram on page 8. This diagram can serve you in several ways: It is a summary of the procedure that you are to follow in classifying your unknown as one of the functional group types. It can order your thoughts as you read the discussion of each test, and help you to understand the significance of that test. It can enhance your appreciation for and enjoyment of this experiment. Your role is that of chemist and detective: you will employ this cleverly devised scheme to sleuth out the identity of your unknown's functionality. Experiment 1 2 Laboratory Experiments for GOB Chemistry ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Discussion of Chemical Tests 1. -

Ester Synthesis Lab (Student Handout)

Name: ________________________ Lab Partner: ____________________ Date: __________________________ Class Period: ____________________ Ester Synthesis Lab (Student Handout) Lab Report Components: The following must be included in your lab book in order to receive full credit. 1. Purpose 2. Hypothesis 3. Procedure 4. Observation/Data Table 5. Results 6. Mechanism (In class) 7. Conclusion Introduction The compounds you will be making are also naturally occurring compounds; the chemical structure of these compounds is already known from other investigations. Esters are organic molecules of the general form: where R1 and R2 are any carbon chain. Esters are unique in that they often have strong, pleasant odors. As such, they are often used in fragrances, and many artificial flavorings are in fact esters. Esters are produced by the reaction between alcohols and carboxylic acids. For example, reacting ethanol with acetic acid to give ethyl acetate is shown below. + → + In the case of ethyl acetate, R1 is a CH3 group and R2 is a CH3CH2 group. Naming esters systematically requires naming the functional groups on both sides of the bridging oxygen. In the example above, the right side of the ester as shown is a CH3CH2 1 group, or ethyl group. The left side is CH3C=O, or acetate. The name of the ester is therefore ethyl acetate. Deriving the names of the side from the carboxylic acid merely requires replacing the suffix –ic with –ate. Materials • Alcohol • Carboxylic Acid o 1 o A o 2 o B o 3 o C o 4 Observation Parameters: • Record the combination of carboxylic acid and alcohol • Observe each reactant • Observe each product Procedure 1.