The Strongest Acid Christopher A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is There an Acid Strong Enough to Dissolve Glass? – Superacids

ARTICLE Is there an acid strong enough to dissolve glass? – Superacids For anybody who watched cartoons growing up, the word unit is based on how acids behave in water, however as acid probably springs to mind images of gaping holes being very strong acids react extremely violently in water this burnt into the floor by a spill, and liquid that would dissolve scale cannot be used for the pure ‘common’ acids (nitric, anything you drop into it. The reality of the acids you hydrochloric and sulphuric) or anything stronger than them. encounter in schools, and most undergrad university Instead, a different unit, the Hammett acidity function (H0), courses is somewhat underwhelming – sure they will react is often preferred when discussing superacids. with chemicals, but, if handled safely, where’s the drama? A superacid can be defined as any compound with an People don’t realise that these extraordinarily strong acids acidity greater than 100% pure sulphuric acid, which has a do exist, they’re just rarely seen outside of research labs Hammett acidity function (H0) of −12 [1]. Modern definitions due to their extreme potency. These acids are capable of define a superacid as a medium in which the chemical dissolving almost anything – wax, rocks, metals (even potential of protons is higher than it is in pure sulphuric acid platinum), and yes, even glass. [2]. Considering that pure sulphuric acid is highly corrosive, you can be certain that anything more acidic than that is What are Superacids? going to be powerful. What are superacids? Its all in the name – super acids are intensely strong acids. -

A Guide to Acids, Acid Strength, and Concentration

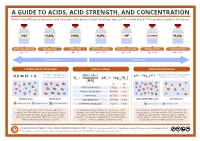

A GUIDE TO ACIDS, ACID STRENGTH, AND CONCENTRATION What’s the difference between acid strength and concentration? And how does pH fit in with these? This graphic explains the basics. CH COOH HCl H2SO4 HNO3 H3PO4 HF 3 H2CO3 HYDROCHLORIC ACID SULFURIC ACID NITRIC ACID PHOSPHORIC ACID HYDROFLUORIC ACID ETHANOIC ACID CARBONIC ACID pKa = –7 pKa = –2 pKa = –2 pKa = 2.12 pKa = 3.45 pKa = 4.76 pKa = 6.37 STRONGER ACIDS WEAKER ACIDS STRONG ACIDS VS. WEAK ACIDS ACIDS, Ka AND pKa CONCENTRATION AND pH + – The H+ ion is transferred to a + A decrease of one on the pH scale represents + [H+] [A–] pH = –log10[H ] a tenfold increase in H+ concentration. HA H + A water molecule, forming H3O Ka = pKa = –log10[Ka] – [HA] – – + + A + + A– + A + A H + H H H H A H + H H H A Ka pK H – + – H a A H A A – + A– A + H A– H A– VERY STRONG ACID >0.1 <1 A– + H A + + + – H H A H A H H H + A – + – H A– A H A A– –3 FAIRLY STRONG ACID 10 –0.1 1–3 – – + A A + H – – + – H + H A A H A A A H H + A A– + H A– H H WEAK ACID 10–5–10–3 3–5 STRONG ACID WEAK ACID VERY WEAK ACID 10–15–10–5 5–15 CONCENTRATED ACID DILUTE ACID + – H Hydrogen ions A Negative ions H A Acid molecules EXTREMELY WEAK ACID <10–15 >15 H+ Hydrogen ions A– Negative ions Acids react with water when they are added to it, The acid dissociation constant, Ka, is a measure of the Concentration is distinct from strength. -

Fluorosulfonic Acid

Fluorosulfonic acid sc-235156 Material Safety Data Sheet Hazard Alert Code EXTREME HIGH MODERATE LOW Key: Section 1 - CHEMICAL PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION PRODUCT NAME Fluorosulfonic acid STATEMENT OF HAZARDOUS NATURE CONSIDERED A HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCE ACCORDING TO OSHA 29 CFR 1910.1200. NFPA FLAMMABILITY0 HEALTH3 HAZARD INSTABILITY2 W SUPPLIER Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. 2145 Delaware Avenue Santa Cruz, California 95060 800.457.3801 or 831.457.3800 EMERGENCY ChemWatch Within the US & Canada: 877-715-9305 Outside the US & Canada: +800 2436 2255 (1-800-CHEMCALL) or call +613 9573 3112 SYNONYMS FSO3H, H-F-O3-S, HSO3F, "fluorosulphonic acid", "fluosulfonic acid", "fluorosulfuric acid" Section 2 - HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION CHEMWATCH HAZARD RATINGS Min Max Flammability 0 Toxicity 2 Body Contact 4 Min/Nil=0 Low=1 Reactivity 2 Moderate=2 High=3 Chronic 2 Extreme=4 CANADIAN WHMIS SYMBOLS 1 of 17 CANADIAN WHMIS CLASSIFICATION CAS 7789-21-1Fluorosulfonic acid E-Corrosive Material 1 F-Dangerously Reactive Material 2 EMERGENCY OVERVIEW RISK Reacts violently with water. Harmful by inhalation. Causes severe burns. Risk of serious damage to eyes. POTENTIAL HEALTH EFFECTS ACUTE HEALTH EFFECTS SWALLOWED ■ The material can produce severe chemical burns within the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract following ingestion. ■ Accidental ingestion of the material may be damaging to the health of the individual. ■ Ingestion of acidic corrosives may produce burns around and in the mouth, the throat and oesophagus. Immediate pain and difficulties in swallowing and speaking may also be evident. ■ Fluoride causes severe loss of calcium in the blood, with symptoms appearing several hours later including painful and rigid muscle contractions of the limbs. -

Catalytic Properties of Zeolites and Synthesized Superacid Systems During the Transformation of Model Reactions of Pentanes

Advances in Engineering Research, volume 177 International Symposium on Engineering and Earth Sciences (ISEES 2018) Catalytic Properties of Zeolites and Synthesized Superacid Systems During the Transformation of Model Reactions of Pentanes Turlov s RA-B. Magomadova Marem .Kh. Heat Engineering and Hydraulics Department of Heat Engineering and Hydraulics Department of Grozny State Oil Technical University Grozny State Oil Technical University g . Grozny, Russia Grozny, Russia e - mail: [email protected] e - mail: [email protected] Madaeva A. D. Idrisova E.U. Heat Engineering and Hydraulics Department Heat Engineering and Hydraulics Department of Grozny State Oil Technical University of Grozny State Oil Technical University Grozny, Russia Grozny, Russia e - mail: ANITA [email protected] e - mail: idrisova999@mail ru Magomadova Madina. Kh. "Chemical technology of oil and gas Department of Grozny State Oil Technical University Grozny, Russia e - mail : [email protected] Abstract—Investigation of the catalytic activity and selectivity II. THE METHODOLOGY OF THE EXPERIMENT of the obtained products of various nature and composition of Before conducting the experiment, the test samples of catalysts in the course of model catalytic reactions, cracking, catalysts (zeolites, AAS and γ-Al2O3) with a fractional isomerization, disproportionation. The study of the acid sites of composition of 0.25 ÷ 40.5 mm were loaded into a quartz these catalysts and their influence on the composition of the reactor, a sample of 0.15 g., the fractional composition of reaction products and the mechanism of conversion of specific C 5 which, as the reactor is filled from the bottom of the reactor to hydrocarbons. The study of the mechanism, speed and direction of the lower part of the catalyst boundary, varies from 2.0 to 0.1 individual stages of multistage reactions implemented scientific mm; then the catalyst and quartz were filled, the fractional and industrial processes. -

Superacid Chemistry

SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SECOND EDITION George A. Olah G. K. Surya Prakash Arpad Molnar Jean Sommer SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SECOND EDITION George A. Olah G. K. Surya Prakash Arpad Molnar Jean Sommer Copyright # 2009 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. -

Introduction to Ionic Mechanisms Part I: Fundamentals of Bronsted-Lowry Acid-Base Chemistry

INTRODUCTION TO IONIC MECHANISMS PART I: FUNDAMENTALS OF BRONSTED-LOWRY ACID-BASE CHEMISTRY HYDROGEN ATOMS AND PROTONS IN ORGANIC MOLECULES - A hydrogen atom that has lost its only electron is sometimes referred to as a proton. That is because once the electron is lost, all that remains is the nucleus, which in the case of hydrogen consists of only one proton. The large majority of organic reactions, or transformations, involve breaking old bonds and forming new ones. If a covalent bond is broken heterolytically, the products are ions. In the following example, the bond between carbon and oxygen in the t-butyl alcohol molecule breaks to yield a carbocation and hydroxide ion. H3C CH3 H3C OH H3C + OH CH3 H3C A tertiary Hydroxide carbocation ion The full-headed curved arrow is being used to indicate the movement of an electron pair. In this case, the two electrons that make up the carbon-oxygen bond move towards the oxygen. The bond breaks, leaving the carbon with a positive charge, and the oxygen with a negative charge. In the absence of other factors, it is the difference in electronegativity between the two atoms that drives the direction of electron movement. When pushing arrows, remember that electrons move towards electronegative atoms, or towards areas of electron deficiency (positive, or partial positive charges). The electron pair moves towards the oxygen because it is the more electronegative of the two atoms. If we examine the outcome of heterolytic bond cleavage between oxygen and hydrogen, we see that, once again, oxygen takes the two electrons because it is the more electronegative atom. -

140. Sulphuric, Hydrochloric, Nitric and Phosphoric Acids

nr 2009;43(7) The Nordic Expert Group for Criteria Documentation of Health Risks from Chemicals 140. Sulphuric, hydrochloric, nitric and phosphoric acids Marianne van der Hagen Jill Järnberg arbete och hälsa | vetenskaplig skriftserie isbn 978-91-85971-14-5 issn 0346-7821 Arbete och Hälsa Arbete och Hälsa (Work and Health) is a scientific report series published by Occupational and Enviromental Medicine at Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg. The series publishes scientific original work, review articles, criteria documents and dissertations. All articles are peer-reviewed. Arbete och Hälsa has a broad target group and welcomes articles in different areas. Instructions and templates for manuscript editing are available at http://www.amm.se/aoh Summaries in Swedish and English as well as the complete original texts from 1997 are also available online. Arbete och Hälsa Editorial Board: Editor-in-chief: Kjell Torén Tor Aasen, Bergen Kristina Alexanderson, Stockholm Co-editors: Maria Albin, Ewa Wigaeus Berit Bakke, Oslo Tornqvist, Marianne Törner, Wijnand Lars Barregård, Göteborg Eduard, Lotta Dellve och Roger Persson Jens Peter Bonde, Köpenhamn Managing editor: Cina Holmer Jörgen Eklund, Linköping Mats Eklöf, Göteborg © University of Gothenburg & authors 2009 Mats Hagberg, Göteborg Kari Heldal, Oslo Arbete och Hälsa, University of Gothenburg Kristina Jakobsson, Lund SE 405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden Malin Josephson, Uppsala Bengt Järvholm, Umeå ISBN 978-91-85971-14-5 Anette Kærgaard, Herning ISSN 0346–7821 Ann Kryger, Köpenhamn http://www.amm.se/aoh -

George A. Olah 151

MY SEARCH FOR CARBOCATIONS AND THEIR ROLE IN CHEMISTRY Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1994 by G EORGE A. O L A H Loker Hydrocarbon Research Institute and Department of Chemistry, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089-1661, USA “Every generation of scientific men (i.e. scientists) starts where the previous generation left off; and the most advanced discov- eries of one age constitute elementary axioms of the next. - - - Aldous Huxley INTRODUCTION Hydrocarbons are compounds of the elements carbon and hydrogen. They make up natural gas and oil and thus are essential for our modern life. Burning of hydrocarbons is used to generate energy in our power plants and heat our homes. Derived gasoline and diesel oil propel our cars, trucks, air- planes. Hydrocarbons are also the feed-stock for practically every man-made material from plastics to pharmaceuticals. What nature is giving us needs, however, to be processed and modified. We will eventually also need to make hydrocarbons ourselves, as our natural resources are depleted. Many of the used processes are acid catalyzed involving chemical reactions proceeding through positive ion intermediates. Consequently, the knowledge of these intermediates and their chemistry is of substantial significance both as fun- damental, as well as practical science. Carbocations are the positive ions of carbon compounds. It was in 1901 that Norris la and Kehrman lb independently discovered that colorless triphe- nylmethyl alcohol gave deep yellow solutions in concentrated sulfuric acid. Triphenylmethyl chloride similarly formed orange complexes with alumi- num and tin chlorides. von Baeyer (Nobel Prize, 1905) should be credited for having recognized in 1902 the salt like character of the compounds for- med (equation 1). -

WO 2016/074683 Al 19 May 2016 (19.05.2016) W P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2016/074683 Al 19 May 2016 (19.05.2016) W P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C12N 15/10 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/DK20 15/050343 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 11 November 2015 ( 11. 1 1.2015) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (25) Filing Language: English PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, (26) Publication Language: English SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: PA 2014 00655 11 November 2014 ( 11. 1 1.2014) DK (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 62/077,933 11 November 2014 ( 11. 11.2014) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 62/202,3 18 7 August 2015 (07.08.2015) US GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, (71) Applicant: LUNDORF PEDERSEN MATERIALS APS TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, [DK/DK]; Nordvej 16 B, Himmelev, DK-4000 Roskilde DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, (DK). -

Characterization of the Acidity of Sio2-Zro2 Mixed Oxides

Characterization of the acidity of SiO2-ZrO2 mixed oxides Citation for published version (APA): Bosman, H. J. M. (1995). Characterization of the acidity of SiO2-ZrO2 mixed oxides. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. https://doi.org/10.6100/IR436698 DOI: 10.6100/IR436698 Document status and date: Published: 01/01/1995 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Isolation and Characterization of a Non-Rigid Hexamethylbenzene-SO 2+ Complex Moritz Malischewski, Konrad Seppelt

Isolation and Characterization of a Non-Rigid Hexamethylbenzene-SO 2+ Complex Moritz Malischewski, Konrad Seppelt To cite this version: Moritz Malischewski, Konrad Seppelt. Isolation and Characterization of a Non-Rigid Hexamethylbenzene-SO 2+ Complex. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, Wiley-VCH Verlag, 2017, 56 (52), pp.16495-16497. 10.1002/anie.201708552. hal-01730776 HAL Id: hal-01730776 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01730776 Submitted on 13 Mar 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Isolation and characterization of a non-rigid hexamethylbenzene- SO2+ complex Moritz Malischewski*[a],[b] and Konrad Seppelt[a] In memoriam of George Olah (1927-2017) Abstract: During our preparation of the pentagonal-pyramidal up besides recrystallization directly from the reaction mixture is 2+ 2+ - hexamethylbenzene-dication C6(CH3)6 we isolated the possible. Although C6(CH3)6SO (AsF6 )2 is the main component 2+ - unprecedented dicationic species C6(CH3)6SO (AsF6 )2 from the of the isolated material, ionic side-products co-precipitate due to reaction of hexamethylbenzene with a mixture of anhydrous HF, their low solubility in HF at low temperatures. AsF5 and liquid SO2. This compound can be understood as a complex of unknown SO2+ with hexamethylbenzene. -

Acid Dissociation Constant - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1

Acid dissociation constant - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 Help us provide free content to the world by donating today ! Acid dissociation constant From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia An acid dissociation constant (aka acidity constant, acid-ionization constant) is an equilibrium constant for the dissociation of an acid. It is denoted by Ka. For an equilibrium between a generic acid, HA, and − its conjugate base, A , The weak acid acetic acid donates a proton to water in an equilibrium reaction to give the acetate ion and − + HA A + H the hydronium ion. Key: Hydrogen is white, oxygen is red, carbon is gray. Lines are chemical bonds. K is defined, subject to certain conditions, as a where [HA], [A−] and [H+] are equilibrium concentrations of the reactants. The term acid dissociation constant is also used for pKa, which is equal to −log 10 Ka. The term pKb is used in relation to bases, though pKb has faded from modern use due to the easy relationship available between the strength of an acid and the strength of its conjugate base. Though discussions of this topic typically assume water as the solvent, particularly at introductory levels, the Brønsted–Lowry acid-base theory is versatile enough that acidic behavior can now be characterized even in non-aqueous solutions. The value of pK indicates the strength of an acid: the larger the value the weaker the acid. In aqueous a solution, simple acids are partially dissociated to an appreciable extent in in the pH range pK ± 2. The a actual extent of the dissociation can be calculated if the acid concentration and pH are known.