APPENDIX G Acid Dissociation Constants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Advisory Group to Recommend Priorities for the IARC Monographs During 2020–2024

IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans Report of the Advisory Group to Recommend Priorities for the IARC Monographs during 2020–2024 Report of the Advisory Group to Recommend Priorities for the IARC Monographs during 2020–2024 CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Acetaldehyde (CAS No. 75-07-0) ................................................................................................. 3 Acrolein (CAS No. 107-02-8) ....................................................................................................... 4 Acrylamide (CAS No. 79-06-1) .................................................................................................... 5 Acrylonitrile (CAS No. 107-13-1) ................................................................................................ 6 Aflatoxins (CAS No. 1402-68-2) .................................................................................................. 8 Air pollutants and underlying mechanisms for breast cancer ....................................................... 9 Airborne gram-negative bacterial endotoxins ............................................................................. 10 Alachlor (chloroacetanilide herbicide) (CAS No. 15972-60-8) .................................................. 10 Aluminium (CAS No. 7429-90-5) .............................................................................................. 11 -

Chapter 21 the Chemistry of Carboxylic Acid Derivatives

Instructor Supplemental Solutions to Problems © 2010 Roberts and Company Publishers Chapter 21 The Chemistry of Carboxylic Acid Derivatives Solutions to In-Text Problems 21.1 (b) (d) (e) (h) 21.2 (a) butanenitrile (common: butyronitrile) (c) isopentyl 3-methylbutanoate (common: isoamyl isovalerate) The isoamyl group is the same as an isopentyl or 3-methylbutyl group: (d) N,N-dimethylbenzamide 21.3 The E and Z conformations of N-acetylproline: 21.5 As shown by the data above the problem, a carboxylic acid has a higher boiling point than an ester because it can both donate and accept hydrogen bonds within its liquid state; hydrogen bonding does not occur in the ester. Consequently, pentanoic acid (valeric acid) has a higher boiling point than methyl butanoate. Here are the actual data: INSTRUCTOR SUPPLEMENTAL SOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMS • CHAPTER 21 2 21.7 (a) The carbonyl absorption of the ester occurs at higher frequency, and only the carboxylic acid has the characteristic strong, broad O—H stretching absorption in 2400–3600 cm–1 region. (d) In N-methylpropanamide, the N-methyl group is a doublet at about d 3. N-Ethylacetamide has no doublet resonances. In N-methylpropanamide, the a-protons are a quartet near d 2.5. In N-ethylacetamide, the a- protons are a singlet at d 2. The NMR spectrum of N-methylpropanamide has no singlets. 21.9 (a) The first ester is more basic because its conjugate acid is stabilized not only by resonance interaction with the ester oxygen, but also by resonance interaction with the double bond; that is, the conjugate acid of the first ester has one more important resonance structure than the conjugate acid of the second. -

Group 17 (Halogens)

Sodium, Na Gallium, Ga CHEMISTRY 1000 Topic #2: The Chemical Alphabet Fall 2020 Dr. Susan Findlay See Exercises 11.1 to 11.4 Forms of Carbon The Halogens (Group 17) What is a halogen? Any element in Group 17 (the only group containing Cl2 solids, liquids and gases at room temperature) Exists as diatomic molecules ( , , , ) Melting Boiling 2State2 2 2Density Point Point (at 20 °C) (at 20 °C) Fluorine -220 °C -188 °C Gas 0.0017 g/cm3 Chlorine -101 °C -34 °C Gas 0.0032 g/cm3 Br2 Bromine -7.25 °C 58.8 °C Liquid 3.123 g/cm3 Iodine 114 °C 185 °C Solid 4.93 g/cm3 A nonmetal I2 Volatile (evaporates easily) with corrosive fumes Does not occur in nature as a pure element. Electronegative; , and are strong acids; is one of the stronger weak acids 2 The Halogens (Group 17) What is a halogen? Only forms one monoatomic anion (-1) and no free cations Has seven valence electrons (valence electron configuration . ) and a large electron affinity 2 5 A good oxidizing agent (good at gaining electrons so that other elements can be oxidized) First Ionization Electron Affinity Standard Reduction Energy (kJ/mol) Potential (kJ/mol) (V = J/C) Fluorine 1681 328.0 +2.866 Chlorine 1251 349.0 +1.358 Bromine 1140 324.6 +1.065 Iodine 1008 295.2 +0.535 3 The Halogens (Group 17) Fluorine, chlorine and bromine are strong enough oxidizing agents that they can oxidize the oxygen in water! When fluorine is bubbled through water, hydrogen fluoride and oxygen gas are produced. -

Oxalic Acid As a Heterogeneous Ice Nucleus in the Upper Troposphere and Its Indirect Aerosol Effect” by B

Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss., 6, S1765–S1768, 2006 Atmospheric www.atmos-chem-phys-discuss.net/6/S1765/2006/ Chemistry ACPD c Author(s) 2006. This work is licensed and Physics 6, S1765–S1768, 2006 under a Creative Commons License. Discussions Interactive Comment Interactive comment on “Oxalic acid as a heterogeneous ice nucleus in the upper troposphere and its indirect aerosol effect” by B. Zobrist et al. B. Zobrist et al. Received and published: 13 July 2006 The authors would like to thank anonymous referee #1 for his/her constructive comments. We have addressed the referee’s concerns point-by-point below. Full Screen / Esc Succinic and Adipic acid as immersion IN: The solubility of these dicarboxylic acids is very low at temperatures of about 235 K, Printer-friendly Version as supported by the deliquescence measurements of Parsons et al. (JGR 109, D06212, 2004) which are close to 100 % RH. In our experiments, the droplets of Interactive Discussion these acids are completely liquid in the first cooling cycle with concentrations of Discussion Paper 7.3 wt% for succinic acid and 1.6 wt% for adipic acid, which is why they nucleate ice S1765 EGU homogeneously at temperatures below that of pure water. When the acids precipitate, the concentration of the remaining liquid corresponds to the equilibrium solubility at ACPD each temperature when the samples are cooled in the second cycle. Because of the 6, S1765–S1768, 2006 low solubility at lower temperatures we expect the observed rise in the homogeneous ice nucleation temperature when compared to the first cooling run. In fact, if we use the measured freezing temperatures and assume they are due to homogeneous ice Interactive nucleation, we can use water-activity-based ice nucleation theory to deduce the water Comment activity of the liquid part of the samples. -

Not ACID, Not BASE, but SALT a Transaction Processing Perspective on Blockchains

Not ACID, not BASE, but SALT A Transaction Processing Perspective on Blockchains Stefan Tai, Jacob Eberhardt and Markus Klems Information Systems Engineering, Technische Universitat¨ Berlin fst, je, [email protected] Keywords: SALT, blockchain, decentralized, ACID, BASE, transaction processing Abstract: Traditional ACID transactions, typically supported by relational database management systems, emphasize database consistency. BASE provides a model that trades some consistency for availability, and is typically favored by cloud systems and NoSQL data stores. With the increasing popularity of blockchain technology, another alternative to both ACID and BASE is introduced: SALT. In this keynote paper, we present SALT as a model to explain blockchains and their use in application architecture. We take both, a transaction and a transaction processing systems perspective on the SALT model. From a transactions perspective, SALT is about Sequential, Agreed-on, Ledgered, and Tamper-resistant transaction processing. From a systems perspec- tive, SALT is about decentralized transaction processing systems being Symmetric, Admin-free, Ledgered and Time-consensual. We discuss the importance of these dual perspectives, both, when comparing SALT with ACID and BASE, and when engineering blockchain-based applications. We expect the next-generation of decentralized transactional applications to leverage combinations of all three transaction models. 1 INTRODUCTION against. Using the admittedly contrived acronym of SALT, we characterize blockchain-based transactions There is a common belief that blockchains have the – from a transactions perspective – as Sequential, potential to fundamentally disrupt entire industries. Agreed, Ledgered, and Tamper-resistant, and – from Whether we are talking about financial services, the a systems perspective – as Symmetric, Admin-free, sharing economy, the Internet of Things, or future en- Ledgered, and Time-consensual. -

Failures in DBMS

Chapter 11 Database Recovery 1 Failures in DBMS Two common kinds of failures StSystem filfailure (t)(e.g. power outage) ‒ affects all transactions currently in progress but does not physically damage the data (soft crash) Media failures (e.g. Head crash on the disk) ‒ damagg()e to the database (hard crash) ‒ need backup data Recoveryyp scheme responsible for handling failures and restoring database to consistent state 2 Recovery Recovering the database itself Recovery algorithm has two parts ‒ Actions taken during normal operation to ensure system can recover from failure (e.g., backup, log file) ‒ Actions taken after a failure to restore database to consistent state We will discuss (briefly) ‒ Transactions/Transaction recovery ‒ System Recovery 3 Transactions A database is updated by processing transactions that result in changes to one or more records. A user’s program may carry out many operations on the data retrieved from the database, but the DBMS is only concerned with data read/written from/to the database. The DBMS’s abstract view of a user program is a sequence of transactions (reads and writes). To understand database recovery, we must first understand the concept of transaction integrity. 4 Transactions A transaction is considered a logical unit of work ‒ START Statement: BEGIN TRANSACTION ‒ END Statement: COMMIT ‒ Execution errors: ROLLBACK Assume we want to transfer $100 from one bank (A) account to another (B): UPDATE Account_A SET Balance= Balance -100; UPDATE Account_B SET Balance= Balance +100; We want these two operations to appear as a single atomic action 5 Transactions We want these two operations to appear as a single atomic action ‒ To avoid inconsistent states of the database in-between the two updates ‒ And obviously we cannot allow the first UPDATE to be executed and the second not or vice versa. -

Rate Constants for Reactions Between Iodine- and Chlorine-Containing Species: a Detailed Mechanism of the Chlorine Dioxide/Chlorite-Iodide Reaction†

3708 J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 3708-3719 Rate Constants for Reactions between Iodine- and Chlorine-Containing Species: A Detailed Mechanism of the Chlorine Dioxide/Chlorite-Iodide Reaction† Istva´n Lengyel,‡ Jing Li, Kenneth Kustin,* and Irving R. Epstein Contribution from the Department of Chemistry and Center for Complex Systems, Brandeis UniVersity, Waltham, Massachusetts 02254-9110 ReceiVed NoVember 27, 1995X Abstract: The chlorite-iodide reaction is unusual because it is substrate-inhibited and autocatalytic. Because - analytically pure ClO2 ion is not easily prepared, it was generated in situ from the rapid reaction between ClO2 and I-. The resulting overall reaction is multiphasic, consisting of four separable parts. Sequentially, beginning with mixing, these parts are the (a) chlorine dioxide-iodide, (b) chlorine(III)-iodide, (c) chlorine(III)-iodine, and (d) hypoiodous and iodous acid disproportionation reactions. The overall reaction has been studied experimentally and by computer simulation by breaking it down into a set of kinetically active subsystems and three rapidly established - equilibria: protonations of chlorite and HOI and formation of I3 . The subsystems whose kinetics and stoichiometries were experimentally measured, remeasured, or which were previously experimentally measured include oxidation of - iodine(-1,0,+1,+3) by chlorine(0,+1,+3), oxidation of I by HIO2, and disproportionation of HOI and HIO2. The final mechanism and rate constants of the overall reaction and of its subsystems were determined by sensitivity analysis and parameter fitting of differential equation systems. Rate constants determined for simpler reactions were fixed in the more complex systems. A 13-step model with the three above-mentioned rapid equilibria fits the - -3 - -3 - - overall reaction and all of its subsystems over the range [I ]0 < 10 M, [ClO2 ]0 < 10 M, [I ]0/[ClO2 ]0 ) 3-5, pH ) 1-3.5, and 25 °C. -

Toxicological Review of Chloral Hydrate (CAS No. 302-17-0) (PDF)

EPA/635/R-00/006 TOXICOLOGICAL REVIEW OF CHLORAL HYDRATE (CAS No. 302-17-0) In Support of Summary Information on the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) August 2000 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Washington, DC DISCLAIMER This document has been reviewed in accordance with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency policy and approved for publication. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. Note: This document may undergo revisions in the future. The most up-to-date version will be made available electronically via the IRIS Home Page at http://www.epa.gov/iris. ii CONTENTS—TOXICOLOGICAL REVIEW for CHLORAL HYDRATE (CAS No. 302-17-0) FOREWORD .................................................................v AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, AND REVIEWERS ................................ vi 1. INTRODUCTION ..........................................................1 2. CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL INFORMATION RELEVANT TO ASSESSMENTS ..... 2 3. TOXICOKINETICS RELEVANT TO ASSESSMENTS ............................3 4. HAZARD IDENTIFICATION ................................................6 4.1. STUDIES IN HUMANS - EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CASE REPORTS .................................................6 4.2. PRECHRONIC AND CHRONIC STUDIES AND CANCER BIOASSAYS IN ANIMALS ................................8 4.2.1. Oral ..........................................................8 4.2.2. Inhalation .....................................................12 4.3. REPRODUCTIVE/DEVELOPMENTAL STUDIES ..........................13 -

SQL Vs Nosql: a Performance Comparison

SQL vs NoSQL: A Performance Comparison Ruihan Wang Zongyan Yang University of Rochester University of Rochester [email protected] [email protected] Abstract 2. ACID Properties and CAP Theorem We always hear some statements like ‘SQL is outdated’, 2.1. ACID Properties ‘This is the world of NoSQL’, ‘SQL is still used a lot by We need to refer the ACID properties[12]: most of companies.’ Which one is accurate? Has NoSQL completely replace SQL? Or is NoSQL just a hype? SQL Atomicity (Structured Query Language) is a standard query language A transaction is an atomic unit of processing; it should for relational database management system. The most popu- either be performed in its entirety or not performed at lar types of RDBMS(Relational Database Management Sys- all. tems) like Oracle, MySQL, SQL Server, uses SQL as their Consistency preservation standard database query language.[3] NoSQL means Not A transaction should be consistency preserving, meaning Only SQL, which is a collection of non-relational data stor- that if it is completely executed from beginning to end age systems. The important character of NoSQL is that it re- without interference from other transactions, it should laxes one or more of the ACID properties for a better perfor- take the database from one consistent state to another. mance in desired fields. Some of the NOSQL databases most Isolation companies using are Cassandra, CouchDB, Hadoop Hbase, A transaction should appear as though it is being exe- MongoDB. In this paper, we’ll outline the general differences cuted in iso- lation from other transactions, even though between the SQL and NoSQL, discuss if Relational Database many transactions are execut- ing concurrently. -

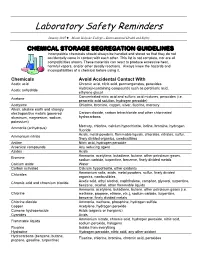

CHEMICAL STORAGE SEGREGATION GUIDELINES Incompatible Chemicals Should Always Be Handled and Stored So That They Do Not Accidentally Come in Contact with Each Other

Laboratory Safety Reminders January 2007 ♦ Mount Holyoke College – Environmental Health and Safety CHEMICAL STORAGE SEGREGATION GUIDELINES Incompatible chemicals should always be handled and stored so that they do not accidentally come in contact with each other. This list is not complete, nor are all compatibilities shown. These materials can react to produce excessive heat, harmful vapors, and/or other deadly reactions. Always know the hazards and incompatibilities of a chemical before using it. Chemicals Avoid Accidental Contact With Acetic acid Chromic acid, nitric acid, permanganates, peroxides Hydroxyl-containing compounds such as perchloric acid, Acetic anhydride ethylene glycol Concentrated nitric acid and sulfuric acid mixtures, peroxides (i.e. Acetone peracetic acid solution, hydrogen peroxide) Acetylene Chlorine, bromine, copper, silver, fluorine, mercury Alkali, alkaline earth and strongly electropositive metals (powered Carbon dioxide, carbon tetrachloride and other chlorinated aluminum, magnesium, sodium, hydrocarbons potassium) Mercury, chlorine, calcium hypochlorite, iodine, bromine, hydrogen Ammonia (anhydrous) fluoride Acids, metal powders, flammable liquids, chlorates, nitrates, sulfur, Ammonium nitrate finely divided organics, combustibles Aniline Nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide Arsenical compounds Any reducing agent Azides Acids Ammonia, acetylene, butadiene, butane, other petroleum gases, Bromine sodium carbide, turpentine, benzene, finely divided metals Calcium oxide Water Carbon activated Calcium hypochlorite, other -

Nomenclature of Carboxylic Acids • Select the Longest Carbon Chain Containing the Carboxyl Group

Chapter 5 Carboxylic Acids and Esters Carboxylic Acids • Carboxylic acids are weak organic acids which Chapter 5 contain the carboxyl group (RCO2H): Carboxylic Acids and Esters O C O H O RCOOH RCO2H Chapter Objectives: O condensed ways of • Learn to recognize the carboxylic acid, ester, and related functional groups. RCOH writing the carboxyl • Learn the IUPAC system for naming carboxylic acids and esters. group a carboxylic acid C H • Learn the important physical properties of the carboxylic acids and esters. • Learn the major chemical reaction of carboxylic acids and esters, and learn how to O predict the products of ester synthesis and hydrolysis reactions. the carboxyl group • Learn some of the important properties of condensation polymers, especially the polyesters. Mr. Kevin A. Boudreaux • The tart flavor of sour-tasting foods is often caused Angelo State University CHEM 2353 Fundamentals of Organic Chemistry by the presence of carboxylic acids. Organic and Biochemistry for Today (Seager & Slabaugh) www.angelo.edu/faculty/kboudrea 2 Nomenclature of Carboxylic Acids • Select the longest carbon chain containing the carboxyl group. The -e ending of the parent alkane name is replaced by the suffix -oic acid. • The carboxyl carbon is always numbered “1” but the number is not included in the name. • Name the substituents attached to the chain in the Nomenclature of usual way. • Aromatic carboxylic acids (i.e., with a CO2H Carboxylic Acids directly connected to a benzene ring) are named after the parent compound, benzoic acid. O C OH 3 -

CHEM 301 Assignment #2 Provide Solutions to the Following Questions in a Neat and Well-Organized Manner

CHEM 301 Assignment #2 Provide solutions to the following questions in a neat and well-organized manner. Reference data sources for any constants and state assumptions, if any. Due date: Thursday, Oct 20th, 2016 Attempt all questions. Only even numbers will be assessed. 1. A pond in an area affected by acid mine drainage is observed to have freshly precipitated Fe(OH)3(s) at pH 4. What is the minimum value of pe in this water? Use the appropriate pe-pH speciation diagram to predict the dominant chemical speciation of carbon, sulfur and copper under these conditions. 2. The solubility of FeS(s) in marine sediments is expected to be affected by the pH and the [H2S(aq)] in the surrounding pore water? Calculate the equilibrium concentration of Fe2+ (ppb) at pH 5 and pH 8, -3 assuming the H2S is 1.0 x 10 M. pKsp(FeS) = 16.84. + 2+ FeS(s) + 2 H (aq) ==== Fe (aq) + H2S 3. Boric acid is a triprotic acid (H3BO3); pKa1 = 9.24, pKa2 = 12.74 and pKa3 = 13.80. a) Derive an expression for the fractional abundance of H3BO3 as a function of pH b) Construct a fully labeled pH speciation diagram for boric acid over the pH range of 0 to 14 using Excel spreadsheet at a 0.2 pH unit interval. 4. At pCl- = 2.0, Cd2+ and CdCl+ are the only dominant cadmium chloride species with a 50% fractional abundance of each. + a) Calculate the equilibrium constant for the formation of CdCl (1). + - b) Derive an expression for the fractional abundance of CdCl as a function of [Cl ] and 1 – 4 for cadmium chloro species.