An Analysis of Selected Cases and Controversies in American Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploitation of the American Progressive Education Movement in Japan’S Postwar Education Reform, 1946-1950

Disarming the Nation, Disarming the Mind: Exploitation of the American Progressive Education Movement in Japan’s Postwar Education Reform, 1946-1950 Kevin Lin Advised by Dr. Talya Zemach-Bersin and Dr. Sarah LeBaron von Baeyer Education Studies Scholars Program Senior Capstone Project Yale University May 2019 i. CONTENTS Introduction 1 Part One. The Rise of Progressive Education 6 Part Two. Social Reconstructionists Aboard the USEM: Stoddard and Counts 12 Part Three. Empire Building in the Cold War 29 Conclusion 32 Bibliography 35 1 Introduction On February 26, 1946, five months after the end of World War II in Asia, a cohort of 27 esteemed American professionals from across the United States boarded two C-54 aircraft at Hamilton Field, a U.S. Air Force base near San Francisco. Following a stop in Honolulu to attend briefings with University of Hawaii faculty, the group was promptly jettisoned across the Pacific Ocean to war-torn Japan.1 Included in this cohort of Americans traveling to Japan was an overwhelming number of educators and educational professionals: among them were George S. Counts, a progressive educator and vice president of the American Federation Teachers’ (AFT) labor union and George D. Stoddard, state commissioner of education for New York and a member of the U.S. delegation to the first meeting of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).2,3 This group of American professionals was carefully curated by the State Department not only for their diversity of backgrounds but also for -

AS Vimed IROM SOCIOLOGICAL and PHILOSOPHICAL BASES

THE PE0BLES4 OF INDOCTRINATION: AS VimED IROM SOCIOLOGICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL BASES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By MiOhio Nagai, B.A., A,M. The Ohio State University 1952 Approvi Adviser H. Gordon flullfish AClSilOWLEDGMiiMT It would be diriicult to express adequately my appreciation of the contributions made by many persons to this study. I first wish to express my gratitude to Dr. H. Gordon Hullfish, my adviser, wnose sincere guidance, generosity, and patience have led me from the first stage of learning in English in July, 194-9, up to the very last minute of completing this dissertation in May, 1952. I am very much indebted to Dr. Aurt H. Wolff whose wisdom and painstaking guidance have been of invaluable help in the writing of this dissertation. Likewise my indebtedness is due Dr. Alan E. Griffin and Dr. Lloyd Williams who read the complete manuscript and made numerous valuable corrections and suggestions. I also wish to express my appreciation for the intellectual stimulation gained for contacts with Dr. John W. Dennett and Mr. Iwao Ishino. Acknowledgment of a less specific, but not necessarily of less important value, is due Dr. Ervin E. Lewis whose kindness guided my first steps in this new land, finally, I wish to thank my wife, Mieko Nagai, without whose help this dissertation might not have been completed. MIGHIO NAGAI 909454 XI TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I INTRODUCTION.......................... 1 I Dictionary Definition.............................. 3 II The Indoctrination Controversy...... -

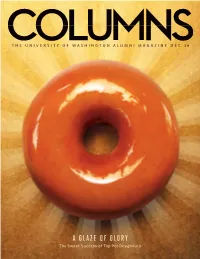

A GLAZE of GLORY the Sweet Success of Top Pot Doughnuts JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE

THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON ALUMNI MAGAZINE DEC 1 4 A GLAZE OF GLORY The Sweet Success of Top Pot Doughnuts JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE 20 ADVANCED DEGREES + 50 CERTIFICATES + 100S OF COURSES AEROSPACE ENGINEERING // PUBLIC HEALTH // C# // APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT BIOSTATISTICS // COMPUTATIONAL FINANCE // MANAGEMENT // PROGRAMMING BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT // INFORMATION SECURITY ANALYTICS // GIS // DATA VISUALIZATION // SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORTATION RUBY // RISK MANAGEMENT // BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE // INFORMATION SYSTEMS PROJECT MANAGEMENT // CONTENT STRATEGY // ORACLE DATABASE ADMIN LOCALIZATION // PARALEGAL // MACHINE LEARNING // SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS BEHAVIORAL HEALTH // GERONTOLOGY // BIOTECHNOLOGY // CIVIL ENGINEERING DEVOPS // DATA SCIENCE // MECHANICAL ENGINEERING // HEALTH CARE // HTML CONTENT STRATEGY // EDUCATION // PROJECT MANAGEMENT // INFORMATICS STATISTICAL ANALYSIS // E-LEARNING // CLOUD DATA MANAGEMENT // EDITING C++ // INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING // LEADERSHIP // BIOSCIENCE // LINGUISTICS INFORMATION SCIENCE // AERONAUTICS & ASTRONAUTICS // APPLIED MATHEMATICS CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING // GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS // PYTHON UW ONLINE 2 COLUMNS MAGAZINE ONLINE.UW.EDU JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE 20 ADVANCED DEGREES + 50 CERTIFICATES + 100S OF COURSES AEROSPACE ENGINEERING // PUBLIC HEALTH // C# // APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT BIOSTATISTICS // COMPUTATIONAL FINANCE // MANAGEMENT // PROGRAMMING BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT // INFORMATION SECURITY ANALYTICS // GIS // DATA VISUALIZATION // -

Critical Education

Critical Education Volume 7 Number 4 March 1, 2016 ISSN 1920-4125 Reconstruction of the Fables The Myth of Education for Democracy, Social Reconstruction and Education for Democratic Citizenship Todd S. Hawley Kent State University Andrew L. Hostetler Peabody College at Vanderbilt University Evan Mooney Montclair State University Citation: Hawley T. S., Hostetler, A. L., & Mooney, E. (2016). Reconstruction of the fables: The myth of education for democracy, social reconstruction and education for democratic citizenship. Critical Education, 7(4). Retrieved from http://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/criticaled/article/view/186116 Abstract A central goal of social studies education is to prepare students for citizenship in a democracy. Further, trends in the social, political, and economic circumstances, currently and historically in American education and society broadly suggest that: 1) a need for change exists, 2) that change is possible and can be brought about through a reconsideration of social reconstructionist ideas and values, especially those espoused by George Counts, and 3) that social studies teachers and teacher educators can work toward this change through educational practices. In this paper, we argue for these three points through a critical discussion of a perpetuated myth of democratic education. Readers are free to copy, display, and distribute this article, as long as the work is attributed to the author(s) and Critical Education, it is distributed for non-commercial purposes only, and no alteration or transformation is made in the work. More details of this Creative Commons license are available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. All other uses must be approved by the author(s) or Critical Education. -

Social Studies and the Social Order: Transmission Or Transformation?

Research and Practice “Research & Practice,” established early in 2001, features educational research that is directly relevant to the work of classroom teachers. Here, Social Studies and I invited William Stanley to bring a historical perspective to the peren- nial question, “Should social studies the Social Order: teachers work to transmit the status quo or to transform it?” Transmission or —Walter C. Parker, “Research and Practice” Editor, University of Transformation? Washington, Seattle. William B. Stanley Should social studies educators The Quest for Democracy and schools are places where chil- transmit or transform the social order? Debates over education reform take dren receive formal training as citizens. By “transform” I do not mean the com- place within a powerful historical and Democracy is also a process or form mon view that education should make cultural context. In the United States, of life rather than a fixed end in itself, society better (e.g., lead to scientific schooling is generally understood as and we should regard any democratic breakthroughs, eradicate disease, and an integral component of a democratic society as a work in progress.1 Thus, increase productivity). Rather, I am society. To the extent we are a demo- democratic society is something we are referring to approaches to education cratic society, one could argue that edu- always trying simultaneously to main- that are critical of the dominant social cation for social transformation could tain and reconstruct, and education is order and motivated by a desire to be anti-democratic, a view held by essential to this process. ensure both political and economic many conservatives. -

An ERIC Paper

An ERIC Paper ALTERNATIVE EDUCATION: THE FREE SCHOOL MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES By Allen Graubard September 1972 /ssued by the ER/C Clearinghouse on Media and Technolool Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305 U.S. DEPARTMLNT DF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY. ALTERNATIVE EDUCATION: THE FREE SCHOOL MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES By Allen Graubard September 1972 Issued by the ERIC Clearinghouse on Media and Technology Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Experience both within andoutside thc system makes Allen Graubard a knowledgeable author for such a paper as this. A Harvard man, Dr. Graubard was director of The Community School, a free elementary and high school in Santa Barbara, California. He served as director of the New Schools Directory Project, funded by the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and has been an editor for New Schools Exchange Newsletter. Most recently, Dr. Graubard was on assignment as Special Assistant to the President for Community-Based Educational Programs at Goddard College, Plainfield, Vermont. TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Author Introduction 1 The Free School Movement: Theory and Practice 2 Pedagogical Source 2 Political Source 3 The Current State of Free Schools 4 Kinds of Free Schools 6 Summerhillian 6 Parent-Teacher Cooperative Elementary 6 Free High Schools 6 Community Elementary 7 Political and Social Issues 9 Wain the System: Some Predictions 11 Resources 13 Journals 13 Books and Articles 13 Useful Centers, Clearinghouses, and People Involved with Free Schools 15 4 INTRODUCTION Approximately nine out of every ten children in the United States attend the public schools. -

Home Schooling: Are Partnerships Possible?

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: HOME SCHOOLING: ARE PARTNERSHIPS POSSIBLE? Kristine L. Angelis, Doctor of Philosophy, 2008 Dissertation directed by: Professor Robert Croninger Department of Education Home schooling has been described as both the oldest and newest form of education, and as the number of home school students continues to grow, a partnership is beginning to evolve with their local school systems. Some states are offering a variety of educational resources to these students which may include participation in extracurricular activities, classroom instruction, or virtual learning opportunities. This exploratory case study is designed to better understand a parent’s choice to home school within the social and institutional framework available to them in Maryland. Maryland offers home schooling families a choice of monitoring options, through their local public school system or a bona fide church exempt organization. The state does not offer home schooling families any additional educational resources except the opportunity to participate in standardized testing. Home schooling parents monitored through a local public school system located in the Baltimore-Washington-Northern Virginia Combined Statistical Area were asked to complete a questionnaire designed to ascertain family characteristics and reasons to home school. Respondents were categorized according to their reason to home school – religious/moral, academic, or other. Eight families were randomly chosen from the three categories to participate in a personal interview to discuss their choice to home school, experiences and challenges of home schooling, and if they would be interested in having services made available to them through their local public school system. Analysis of questionnaire findings and interviews indicated some similarities between the target population and results of the 2003 National Center for Education Statistics survey with the majority in both surveys indicating religion as a main reason to home school. -

Download File

1 Teacher Voice Jonathan Gyurko Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 2 © 2012 Jonathan Gyurko All rights reserved ABSTRACT Teacher Voice Jonathan Gyurko In many of today’s education debates, “teacher voice” is invoked as a remedy to, or the cause of, the problems facing public schools. Advocates argue that teachers don’t have a sufficient voice in setting educational policy and decision-making while critics maintain that teachers have too strong an influence. This study aims to bring some clarity to the contested and often ill-defined notion of “teacher voice.” I begin with an original analytical framework to establish a working definition of teacher voice and a means by which to study teachers’ educational, employment, and policy voice, as expressed individually and collectively, to their colleagues, supervisors, and policymakers. I then use this framework in Part I of my paper which is a historical review of the development and expression of teacher voice over five major periods in the history of public education in the United States, dating from the colonial era through today. Based on this historical interpretation and recent empirical research, I estimate the impact of teacher voice on two outcomes of interest: student achievement and teacher working conditions. In Part II of the paper, I conduct an original quantitative study of teacher voice, designed along the lines of my analytical framework, with particular attention to the relationship between teacher voice and teacher turnover, or “exit.” As presented in Parts I and II and summarized in my Conclusion, teacher voice requires an enabling context. -

Countering the Neos: Dewey and a Democratic Ethos in Teacher Education

Countering the Neos Dewey and a Democratic Ethos in Teacher Education Jamie C. Atkinson (University of Georgia) Abstract Neoliberalism and neoconservatism are two ideologies that currently plague education. The individualistic free- market ideology of neoliberalism and the unbridled nationalistic exceptionalism associated with neo- conservatism often breed a narrowed, overstandardized curriculum and a hyper- testing environment that discourage critical intellectual practice and democratic ideas. Dewey’s philosophy of education indicates that he understood that education is political and can be undemocratic. Dewey’s holistic pragmatism, combined with aspects of social reconstructionism, called for a philosophical movement that favors democratic school- ing. This paper defines neoliberal and neoconservative ideologies and makes a case for including more cri- tique within teacher preparation programs, what Dewey and other educationists referred to as developing a significant social intelligence in teachers. Critical studies embedded within teacher education programs are best positioned to counter the undemocratic forces prevalent in the ideologies of neoliberalism and neocon- servatism. My conclusions rely on Dewey’s philosophy from his work Democracy and Education. Submit a response to this article Submit online at democracyeducationjournal .org/ home Read responses to this article online http:// democracyeducationjournal .org/ home/ vol25/ iss2/ 2 We are living in times when private and public aims and policies are at the direction of our country and our educational systems. During strife with each other. The sum of the matter is that the times are various periods, tensions over the nature, structure, and direction out of joint, and that teachers cannot escape even if they would, some of education have increased in response to ideological and socio- responsibility for a share in putting them right. -

An Historical Analysis of George S. Counts's Concept of the American Public Secondary School with Special Reference to Equality and Selectivity

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1993 An historical analysis of George S. Counts's concept of the American public secondary school with special reference to equality and selectivity Eunice D. Madon Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Madon, Eunice D., "An historical analysis of George S. Counts's concept of the American public secondary school with special reference to equality and selectivity" (1993). Dissertations. 3052. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3052 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1993 Eunice D. Madon AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF GEORGE S. COUNTS'S CONCEPT OF THE AMERICAN PUBLIC SECONDARY SCHOOL WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO EQUALITY AND SELECTIVITY by Eunice D. Madon A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 1993 Copyright by Eunice D. Madon, January 1993 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this dissertation could not have been accomplished without the support, encouragement, and dedication of many people. The writer wishes to express her appreciation to all who helped. First and foremost the author wishes to thank God for giving her the health, ability, and perseverance to complete this paper. -

Educational System from a Socialist Perspective. Based on the Idea That

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 120 051 SO 008 948 AUTHOR Peterson, Robert TITLE Unfair to Young People; How the Public Schools Got the Way They Are. PUB DATE Jun 75 VOTE 53p. AVAILABLE FROMYouth Liberation, 2007 Washtenaw, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104 ($0.65, bulk rate available on request, softbound) EDRS PRICE NP-$0.83 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Capitalism; Educational Alternatives; *Educational Change; Educational Development; *Educational. History; Educational Philosophy; Educational Practice; Elementary Secondary Education; *Political Influences; Political Socialization; *Socialism; Socioeconomic Influences; United States. History ABSTRACT This booklet provides an analysis of the American educational system from a socialist perspective. Based on the idea that our past and present educational system has been largely determined by the needs and ideology of the capitalist economic system, the author proposes an alternative society and educational system that places human needs above private profit. The booklet is divided into three sections which analyze the paste present, and alternative future educational systems. The first section examines how the capitalist ideology influenced the development of our educational system through such concepts as tracking, political indoctrination in history courses, and the direct and indirect capitalistic control of school administration. Section two explains the school socialization process under capitalism and how the capitalist system benefits from this process. It focuses on how punctuality and attendance, obedience to authority, competition and individualism, sexism and racism, and acceptance of boredom contribute to the capitalist ideology. Section three outlines the Chinese and Cuban educational systems as examples of socialist countries that have made great strides in the development of their educational systems. -

Inspiring Student Empowerment, Patti Drapeau Focuses the Spotlight on Meeting the Social, Emotional, and Instructional Needs of Students in the Classroom

INCLUDES DIGITAL Patti Drapeau CONTENT LINK Drapeau Inspiring EM MENT Moving Beyond Engagement, Refining Differentiation © 2020 Free Spirit Publishing Inc. All rights reserved. Praise for Inspiring EM MENT “In her latest work, Inspiring Student Empowerment, Patti Drapeau focuses the spotlight on meeting the social, emotional, and instructional needs of students in the classroom. This book brings student voice and empowerment center stage, which is exactly as it should be. The many, varied strategies that she includes to support effective student learning and engagement are both realistic and user-friendly. Kudos to Drapeau for continuing to highlight the importance of the connection between the teacher and the learner as they create an effective learning environment for all students. Well done!” —Dr. Anita M. Campbell, University of Maine at Farmington “This powerful, insightful, and thought-provoking book adds a new dimension to teaching and learning. The four main areas of emphasis are differentiation, personalized learning, engagement, and empowerment. How these concepts differ and how they interact with and build on one another is the focus of this book. Throughout her practical book, author Patti Drapeau shows teachers and administrators ways to empower students to be self-directed, responsible, and confident learners. This book contains a plethora of excellent ideas—such as using games and competitions to develop student empowerment and giving students choices in designing their own learning concepts and activities. Finally, Drapeau