Sixthchancellor00bowkrich.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

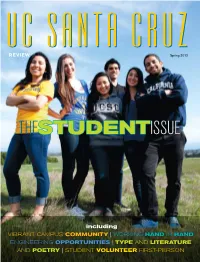

Thestudentissue

UC SANTA CRUZSpring 2013 UC SANTA CRUZREVIEW THESTUDENTISSUE including VIBRANT CAMPUS COMMUNITY | WORKING HAND IN HAND ENGINEERING OPPORTUNITIES | TYPE AND LITERATURE AND POETRY | STUDENT VOLUNTEER FIRST-PERSON UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ Chancellor George Blumenthal Vice Chancellor, University Relations Donna Murphy UC SANTA CRUZ REVIEW Spring 2013 photo: jim mackenzie Editor Gwen Jourdonnais Creative Director Lisa Nielsen Art Director/Designer Linda Knudson (Cowell ’76) From the Chancellor Associate Editor Dan White Cover Photo Carolyn Lagattuta They are smart and hardworking. The admitted Tenacious, imaginative, freshman class for fall 2012 had an average high Photography school GPA of nearly 3.8. Carolyn Lagattuta conscientious—and bright! Jim MacKenzie Our students are also whimsical, fun, creative, Elena Zhukova When I walk around campus, I’m gratified and and innovative—think hipster glasses and flowered inspired by UCSC students. I see students en- velvet Doc Martens—in addition to being tutors, Contributors gaged in the full range of academic and creative mentors, and volunteers. Amy Ettinger Guy Lasnier (Merrill ’78) pursuits, as well as extracurricular activities. This They are active—and we’re ready for them, with Scott Rappaport issue of Review celebrates our students. more than 100 student organizations, 14 men’s Tim Stephens Peggy Townsend Who are today’s students? and women’s NCAA intercollegiate teams, and a Dan White To give you an idea, consider our most recent wide variety of athletic clubs, intramural leagues, and rec programs. Produced by applicant pool. More than 46,000 prospective UC Santa Cruz undergraduates—the most ever—applied for admis- Banana Slugs revel in our broad academic offer- Communications sion to UCSC for the fall 2013 quarter. -

Senate Chairs 1963-1999

Senate Chairs 1963-1999 Leonard Mathy CSC Los Angeles 1963-64 Samuel Wiley CSC Long Beach 1964-65 John Livingston Sacramento State 1965-66 Jesse Allen CSC Los Angeles 1966-67 Sol Buchalter San Fernando Valley State 1967-68 John Stafford San Fernando Valley State 1968-69 Jerome Richfield San Fernando Valley State 1969-70 Levern Graves CSC Fullerton 1970-71 David Provost Fresno State 1971-72 Charles Adams CSU Chico 1972-75 Gerald Marley CSU Fullerton 1975-77 David Elliott San Jose State 1977-79 Robert Kully CSU Los Angeles 1979-82 John Bedell CSU Fullerton 1982-84 Bernard Goldstein San Francisco State 1984-87 Ray Geigle CSU Bakersfield 1987-90 Sandra Wilcox CSU Dominguez Hills 1990-93 Harold Goldwhite CSU Los Angeles 1993-95 James Highsmith CSU Fresno 1995-98 Gene Dinielli CSU Long Beach 1998- v Section I From the History of the Academic Senate of the California State University This section of the Papers consists of presentations which selectively provide a perspective on the history of the statewide Academic Senate. The first paper is a brief social history of its early development. An orientation luncheon for new members of the Senate on September 11, 1987, provided Professor Peter H. Shattuck an opportunity to help prepare those Senators for their new roles. Shattuck approached this occasion as an historian (at CSU Sacramento since 1965), as a former Chair of the Faculty Senate at that campus, and as a member of the Executive Committee of the Academic Senate CSU. Following Professor Shattuck’s speech are the remarks of seven former Chairs of the statewide Academic Senate at a January 9, 1986, Senate symposium commemorating the 25th anniversary of the California State University. -

Exploitation of the American Progressive Education Movement in Japan’S Postwar Education Reform, 1946-1950

Disarming the Nation, Disarming the Mind: Exploitation of the American Progressive Education Movement in Japan’s Postwar Education Reform, 1946-1950 Kevin Lin Advised by Dr. Talya Zemach-Bersin and Dr. Sarah LeBaron von Baeyer Education Studies Scholars Program Senior Capstone Project Yale University May 2019 i. CONTENTS Introduction 1 Part One. The Rise of Progressive Education 6 Part Two. Social Reconstructionists Aboard the USEM: Stoddard and Counts 12 Part Three. Empire Building in the Cold War 29 Conclusion 32 Bibliography 35 1 Introduction On February 26, 1946, five months after the end of World War II in Asia, a cohort of 27 esteemed American professionals from across the United States boarded two C-54 aircraft at Hamilton Field, a U.S. Air Force base near San Francisco. Following a stop in Honolulu to attend briefings with University of Hawaii faculty, the group was promptly jettisoned across the Pacific Ocean to war-torn Japan.1 Included in this cohort of Americans traveling to Japan was an overwhelming number of educators and educational professionals: among them were George S. Counts, a progressive educator and vice president of the American Federation Teachers’ (AFT) labor union and George D. Stoddard, state commissioner of education for New York and a member of the U.S. delegation to the first meeting of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).2,3 This group of American professionals was carefully curated by the State Department not only for their diversity of backgrounds but also for -

AS Vimed IROM SOCIOLOGICAL and PHILOSOPHICAL BASES

THE PE0BLES4 OF INDOCTRINATION: AS VimED IROM SOCIOLOGICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL BASES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By MiOhio Nagai, B.A., A,M. The Ohio State University 1952 Approvi Adviser H. Gordon flullfish AClSilOWLEDGMiiMT It would be diriicult to express adequately my appreciation of the contributions made by many persons to this study. I first wish to express my gratitude to Dr. H. Gordon Hullfish, my adviser, wnose sincere guidance, generosity, and patience have led me from the first stage of learning in English in July, 194-9, up to the very last minute of completing this dissertation in May, 1952. I am very much indebted to Dr. Aurt H. Wolff whose wisdom and painstaking guidance have been of invaluable help in the writing of this dissertation. Likewise my indebtedness is due Dr. Alan E. Griffin and Dr. Lloyd Williams who read the complete manuscript and made numerous valuable corrections and suggestions. I also wish to express my appreciation for the intellectual stimulation gained for contacts with Dr. John W. Dennett and Mr. Iwao Ishino. Acknowledgment of a less specific, but not necessarily of less important value, is due Dr. Ervin E. Lewis whose kindness guided my first steps in this new land, finally, I wish to thank my wife, Mieko Nagai, without whose help this dissertation might not have been completed. MIGHIO NAGAI 909454 XI TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I INTRODUCTION.......................... 1 I Dictionary Definition.............................. 3 II The Indoctrination Controversy...... -

Tenure Clock Extension

11/2/2020 COVID-19 Tenure and Appointment Clock Extension Policy Published on Faculty Handbook (https://facultyhandbook.stanford.edu (https://facultyhandbook.stanford.edu)) Home (/) > Faculty Handbook (/index) > COVID-19 Tenure and Appointment Clock Extension Policy COVID-19 Tenure and Appointment Clock Extension Policy REVISED October 31, 2020 In recognition of the serious academic and personal challenges posed by the Covid-19 viral pandemic, a faculty member holding a tenure-accruing appointment is entitled to a one-year extension of the date (under the seven-year tenure clock) on which tenure would be conferred. This extension will normally have the effect of postponing for a year the initiation of the tenure review process. The Covid-19 Tenure Clock Extension, though it extends the seven-year tenure clock deadline, does not extend the ten-year appointment clock deadline except through an exception granted by the Provost for extraordinary personal or institutional circumstances. The Covid-19 Tenure Clock Extension is available to faculty members holding a tenure-accruing appointment with the exception of those currently in a terminal year appointment or those whose tenure-conferring promotion or reappointment process commenced prior to January 1, 2020, since the work to be evaluated was done prior to the current pandemic. Teaching relief is not associated with this extension. Effective October 1, 2020, this tenure clock extension will be automatically granted to eligible University Tenure Line junior faculty members (as defined above) whose faculty appointments at Stanford will begin prior by December 31, 2021. The extension is not available for faculty members whose tenure-conferring promotion or reappointment process has already commenced (with commencement defined as the date the department chair or school dean informs the candidate in writing that the review process has begun). -

Strength in Numbers: the Rising of Academic Statistics Departments In

Agresti · Meng Agresti Eds. Alan Agresti · Xiao-Li Meng Editors Strength in Numbers: The Rising of Academic Statistics DepartmentsStatistics in the U.S. Rising of Academic The in Numbers: Strength Statistics Departments in the U.S. Strength in Numbers: The Rising of Academic Statistics Departments in the U.S. Alan Agresti • Xiao-Li Meng Editors Strength in Numbers: The Rising of Academic Statistics Departments in the U.S. 123 Editors Alan Agresti Xiao-Li Meng Department of Statistics Department of Statistics University of Florida Harvard University Gainesville, FL Cambridge, MA USA USA ISBN 978-1-4614-3648-5 ISBN 978-1-4614-3649-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-3649-2 Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2012942702 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. -

JOHN WILDER TUKEY 16 June 1915 — 26 July 2000

Tukey second proof 7/11/03 2:51 pm Page 1 JOHN WILDER TUKEY 16 June 1915 — 26 July 2000 Biogr. Mems Fell. R. Soc. Lond. 49, 000–000 (2003) Tukey second proof 7/11/03 2:51 pm Page 2 Tukey second proof 7/11/03 2:51 pm Page 3 JOHN WILDER TUKEY 16 June 1915 — 26 July 2000 Elected ForMemRS 1991 BY PETER MCCULLAGH FRS University of Chicago, 5734 University Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA John Wilder Tukey was a scientific generalist, a chemist by undergraduate training, a topolo- gist by graduate training, an environmentalist by his work on Federal Government panels, a consultant to US corporations, a data analyst who revolutionized signal processing in the 1960s, and a statistician who initiated grand programmes whose effects on statistical practice are as much cultural as they are specific. He had a prodigious knowledge of the physical sci- ences, legendary calculating skills, an unusually sharp and creative mind, and enormous energy. He invented neologisms at every opportunity, among which the best known are ‘bit’ for binary digit, and ‘software’ by contrast with hardware, both products of his long associa- tion with Bell Telephone Labs. Among his legacies are the fast Fourier transformation, one degree of freedom for non-additivity, statistical allowances for multiple comparisons, various contributions to exploratory data analysis and graphical presentation of data, and the jack- knife as a general method for variance estimation. He popularized spectrum analysis as a way of studying stationary time series, he promoted exploratory data analysis at a time when the subject was not academically respectable, and he initiated a crusade for robust or outlier-resist- ant methods in statistical computation. -

The HP Garage—The Birthplace of Silicon Valley 367 Addison Avenue, Palo Alto, California

Brochure A home for innovation The HP Garage—the Birthplace of Silicon Valley 367 Addison Avenue, Palo Alto, California HP Corporate Archives Brochure A home for innovation Tucked away on a quiet, tree-lined residential street near Stanford University, the HP Garage stands today as the enduring symbol of innovation and the entrepreneurial spirit. It was in this humble 12x18-foot building that college friends Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard first pursued the dream of a company of their own. Guided by an unwavering desire to develop innovative and useful products, the two men went on to blaze a trail at the forefront of the electronics revolution. The history of the HP Garage The HP Garage in 1939 (top) and The garage stands behind a two-story Shingle restored in 2005 (bottom). Style home built for Dr. John C. Spencer about 1905. The exact construction date of the garage is unknown, but while there is no evidence of its presence on insurance maps dated 1908, by 1924 it is clearly denoted on updated documents as a private garage. In 1938, Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard decided to “make a run for it” in business. Dave left his job at General Electric in Schenectady, New York, and returned to Palo Alto while Bill scouted rentals. The garage was dedicated as the Birthplace of Silicon Valley in 1989, and HP acquired the He found one perfect for their needs on Addison property in 2000. HP is proud to have worked Avenue. Chosen specifically because of a garage closely with the City of Palo Alto to return the he and Dave could use as their workshop, the house, garage, and shed to conditions much property also offered a three-room, ground- as they were in 1939. -

A GLAZE of GLORY the Sweet Success of Top Pot Doughnuts JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE

THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON ALUMNI MAGAZINE DEC 1 4 A GLAZE OF GLORY The Sweet Success of Top Pot Doughnuts JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE 20 ADVANCED DEGREES + 50 CERTIFICATES + 100S OF COURSES AEROSPACE ENGINEERING // PUBLIC HEALTH // C# // APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT BIOSTATISTICS // COMPUTATIONAL FINANCE // MANAGEMENT // PROGRAMMING BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT // INFORMATION SECURITY ANALYTICS // GIS // DATA VISUALIZATION // SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORTATION RUBY // RISK MANAGEMENT // BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE // INFORMATION SYSTEMS PROJECT MANAGEMENT // CONTENT STRATEGY // ORACLE DATABASE ADMIN LOCALIZATION // PARALEGAL // MACHINE LEARNING // SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS BEHAVIORAL HEALTH // GERONTOLOGY // BIOTECHNOLOGY // CIVIL ENGINEERING DEVOPS // DATA SCIENCE // MECHANICAL ENGINEERING // HEALTH CARE // HTML CONTENT STRATEGY // EDUCATION // PROJECT MANAGEMENT // INFORMATICS STATISTICAL ANALYSIS // E-LEARNING // CLOUD DATA MANAGEMENT // EDITING C++ // INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING // LEADERSHIP // BIOSCIENCE // LINGUISTICS INFORMATION SCIENCE // AERONAUTICS & ASTRONAUTICS // APPLIED MATHEMATICS CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING // GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS // PYTHON UW ONLINE 2 COLUMNS MAGAZINE ONLINE.UW.EDU JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE 20 ADVANCED DEGREES + 50 CERTIFICATES + 100S OF COURSES AEROSPACE ENGINEERING // PUBLIC HEALTH // C# // APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT BIOSTATISTICS // COMPUTATIONAL FINANCE // MANAGEMENT // PROGRAMMING BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT // INFORMATION SECURITY ANALYTICS // GIS // DATA VISUALIZATION // -

Delccm's Silent Science Loveland in Perspective from the Chairman's Desk

Delccm's Silent Science Loveland in perspective from the chairman's desk ITHIK A FEW DAYS we will issue our annual report Another primary objective in 1965 is to achieve a substan . to stockholders covering operations for fiscal 1964. tial increase in our over·all volume of business. To do this, W It was a good year for the company, with sales rising we are going to have to increase the flow of new and im 8 percent to a level of $124.9 million, and incoming orders proved products from our laboratories, and get these prod totaling $130.4, million, also up 8 percent over last year. The ucts into production with greater speed and efficiency than profit picture improved considerably over 1963, with a net ever before. Moreover, we expect our field sales people to do after taxes of $9.4 million, an increase of 29 percent. a more effective job of expanding existing markets for our We were especially gratified at the improvement in our products and tapping new markets, as well. after-tax profit margin from 6.3 cents per sales dollar in 1963 During this next year we will plat'e increasing emphasis to 7.5 cents in 1964. This is largely the result of your day-to on diversification. With the slowup in defense spending and day efforts to reduce costs and do a more effective, produc the expectation that the gOYernment will continue to curtail tive job. or modi£} many at its pro~rams, we are working hard to As you know, we spend a great deal of time talking about broaden our base and expand our technolot\1' into new fields. -

Notices: Highlights

------------- ----- Tacoma Meeting (June 18-20)-Page 667 Notices of the American Mathematical Society June 1987, Issue 256 Volume 34, Number 4, Pages 601 - 728 Providence, Rhode Island USA ISSN 0002-9920 Calendar of AMS Meetings THIS CALENDAR lists all meetings which have been approved by the Council prior to the date this issue of Notices was sent to the press. The summer and annual meetings are joint meetings of the Mathematical Association of America and the American Mathematical Society. The meeting dates which fall rather far in the future are subject to change; this is particularly true of meetings to which no numbers have yet been assigned. Programs of the meetings will appear in the issues indicated below. First and supplementary announcements of the meetings will have appeared in earlier issues. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS presented at a meeting of the Society are published in the journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American Mathematical Society in the issue corresponding to that of the Notices which contains the program of the meeting. Abstracts should be submitted on special forms which are available in many departments of mathematics and from the headquarter's office of the Society. Abstracts of papers to be presented at the meeting must be received at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Island, on or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the deadline for abstracts for consideration for presentation at special sessions is usually three weeks earlier than that specified below. For additional information. consult the meeting announcements and the list of organizers of special sessions. -

Timeline of Computer History

Timeline of Computer History By Year By Category Search AI & Robotics (55) Computers (145)(145) Graphics & Games (48) Memory & Storage (61) Networking & The Popular Culture (50) Software & Languages (60) Bell Laboratories scientist 1937 George Stibitz uses relays for a Hewlett-Packard is founded demonstration adder 1939 Hewlett and Packard in their garage workshop “Model K” Adder David Packard and Bill Hewlett found their company in a Alto, California garage. Their first product, the HP 200A A Called the “Model K” Adder because he built it on his Oscillator, rapidly became a popular piece of test equipm “Kitchen” table, this simple demonstration circuit provides for engineers. Walt Disney Pictures ordered eight of the 2 proof of concept for applying Boolean logic to the design of model to test recording equipment and speaker systems computers, resulting in construction of the relay-based Model the 12 specially equipped theatres that showed the movie I Complex Calculator in 1939. That same year in Germany, “Fantasia” in 1940. engineer Konrad Zuse built his Z2 computer, also using telephone company relays. The Complex Number Calculat 1940 Konrad Zuse finishes the Z3 (CNC) is completed Computer 1941 The Zuse Z3 Computer The Z3, an early computer built by German engineer Konrad Zuse working in complete isolation from developments elsewhere, uses 2,300 relays, performs floating point binary arithmetic, and has a 22-bit word length. The Z3 was used for aerodynamic calculations but was destroyed in a bombing raid on Berlin in late 1943. Zuse later supervised a reconstruction of the Z3 in the 1960s, which is currently on Operator at Complex Number Calculator (CNC) display at the Deutsches Museum in Munich.