Sartoniana Vol 12 1999 092-148.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spontaneous Generation Controversy (340 BCE–1870 CE)

270 4. Abstraction and Unification ∗ ∗ ∗ “O`uen ˆetes-vous? Que faites-vous? Il faut travailler” (on his death-bed, to his devoted pupils, watching over him). The Spontaneous Generation Controversy (340 BCE–1870 CE) “Omne vivium ex Vivo.” (Latin proverb) Although the theory of spontaneous generation (abiogenesis) can be traced back at least to the Ionian school (600 B.C.), it was Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) who presented the most complete arguments for and the clearest statement of this theory. In his “On the Origin of Animals”, Aristotle states not only that animals originate from other similar animals, but also that living things do arise and always have arisen from lifeless matter. Aristotle’s theory of sponta- neous generation was adopted by the Romans and Neo-Platonic philosophers and, through them, by the early fathers of the Christian Church. With only minor modifications, these philosophers’ ideas on the origin of life, supported by the full force of Christian dogma, dominated the mind of mankind for more that 2000 years. According to this theory, a great variety of organisms could arise from lifeless matter. For example, worms, fireflies, and other insects arose from morning dew or from decaying slime and manure, and earthworms originated from soil, rainwater, and humus. Even higher forms of life could originate spontaneously according to Aristotle. Eels and other kinds of fish came from the wet ooze, sand, slime, and rotting seaweed; frogs and salamanders came from slime. 1846 CE 271 Rather than examining the claims of spontaneous generation more closely, Aristotle’s followers concerned themselves with the production of even more remarkable recipes. -

Feathers Gin List Updated 13Th November

Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca “Of all the Gin joints in all the world she had to walk into mine” Welcome, To the Wonderful World of Gin… Gin started life in the early 17th century in Holland, although claims have been made that it was produced prior to this in Italy. WC Fields would start the day with two double martinis, enjoyed either side of his breakfast. He drank about two quarts of gin a day. Every Gin brand has its own unique fragrance; most consumers have probably only tasted a small number of the gin brands available. In ours there are more than 60 different Gin brands, from 9 different countries; offering a wide spectrum of fragrances, using different botanicals and infusion methods in all shapes and sizes. Gin is distilled differently. Premium Gins are distilled 3 to 5 times to remove impurities; each brand has a unique formula that provides its special characteristics. The favourite drink of former President Gerald Ford is Gin and Tonic. Gin is the only alcohol liquor that was first developed as a medicine remedy before it became popular as a social drink. “Mother’s Ruin” a term that came from British soldiers taste for Gin when home on leave from the World War II, and the maternal state it induced in the women who shared their off-duty conviviality. William of Orange prohibited the importing of alcohol to England in the early 18th Century encouraging the production and consumption of English Gin. The excessive consumption that followed gave rise to the name Gin Craze. -

Transfer of Islamic Science to the West

Transfer of Islamic Science to the West IMPORTANT NOTICE: Author: Prof. Dr. Ahmed Y. Al-Hassan Chief Editor: Prof. Dr. Mohamed El-Gomati All rights, including copyright, in the content of this document are owned or controlled for these purposes by FSTC Limited. In Production: Savas Konur accessing these web pages, you agree that you may only download the content for your own personal non-commercial use. You are not permitted to copy, broadcast, download, store (in any medium), transmit, show or play in public, adapt or Release Date: December 2006 change in any way the content of this document for any other purpose whatsoever without the prior written permission of FSTC Publication ID: 625 Limited. Material may not be copied, reproduced, republished, Copyright: © FSTC Limited, 2006 downloaded, posted, broadcast or transmitted in any way except for your own personal non-commercial home use. Any other use requires the prior written permission of FSTC Limited. You agree not to adapt, alter or create a derivative work from any of the material contained in this document or use it for any other purpose other than for your personal non-commercial use. FSTC Limited has taken all reasonable care to ensure that pages published in this document and on the MuslimHeritage.com Web Site were accurate at the time of publication or last modification. Web sites are by nature experimental or constantly changing. Hence information published may be for test purposes only, may be out of date, or may be the personal opinion of the author. Readers should always verify information with the appropriate references before relying on it. -

Warme Dranken Likeur Aperitief Divers Frisdranken Cognac

Warme dranken Frisdranken Bieren WARME GETRÄNKE FRISCHE GETRÄNKE HOT DRINKS SODAS Van de tap: Grolsch 0,3 3,50 Koffi e 2,80 Chaudfontaine 75 cl 6,60 Grolsch 0,5 5,50 Thee 2,60 Chaudfontaine 25 cl 2,60 Grolsch Weizen 0,3 4,50 Verse muntthee 3,80 Fuze Tea sparkling 3,20 Grolsch Weizen 0,5 6,50 Verse gemberthee 3,80 Fuze Tea green mango 3,20 Grimbergen blond/dubbel 0,3 4,50 Espresso 2,60 Thomas Henry mango 3,40 Grimbergen blond/dubbel 0,5 6,50 Cappuccino 3,20 Fanta Orange/ Cassis 2,80 Koffi e Verkeerd 3,20 Thomas Henry Uit de fl es: Latte Macchiato 3,50 Pink Grapefruit 3,40 Grolsch Radler 0% / 2% 3,50 Warme Chocomel 3,20 Schulp perensap 3,20 Heineken 0,3 3,50 Irish/Spanish/Italian Coffee 7,50 Schulp sinaasappelsap 3,20 Heineken 0% 3,50 Special Coffee 7,50 Sprite 2,80 Grolsch Weizen 0% 3,50 Verse Jus d’orange 4,50 Duvel 5,00 Thomas Henry bitter lemon 3,40 Kriek BOON 4,50 Royal Bliss tonic 3,40 La Trappe Tripel 5,00 Likeur Royal Bliss ginger ale 3,40 Desperados 4,00 I love Zeeland appelsap 3,50 Wasschappels blond 5,00 Grand Marnier Rouge 5,00 Apfelschorle 3,50 Cointreau 5,00 Coca Cola/ Cola zero 2,80 Tia Maria 4,50 Thomas Henry ginger beer 3,40 Baileys Irish Cream 4,50 cocktails Amaretto 4,50 Licor 43 4,50 Rosey’s Watermelon 9,00 Villa Massa limoncello 4,50 Cognac Moscow Mule 8,50 Mojito 9,50 Courvoisier v.s.o.p. -

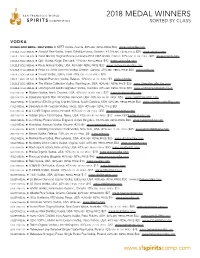

2018 Medal Winners Sorted by Class

2018 MEDAL WINNERS SORTED BY CLASS VODKA DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL / BEST VODKA ■ NEFT Vodka, Austria 49% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $30 www.neftvodka.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Absolut Raw Vodka, Travel Retail Exclusive, Sweden 41.5% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $26 www.absolut.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Casa Maestri Original Premium Handcrafted 1965 Vodka, France 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $20 www.mexcor.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ CpH Vodka, Køge, Denmark 44% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $40 www.cphvodka.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Party Animal Vodka, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $23 www.partyanimalvodka.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Polar Ice Arctic Extreme Vodka, Ontario, Canada 45% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $28 www.corby.ca DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Simple Vodka, Idaho, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $25 DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Svayak Premium Vodka, Belarus 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $4 www.mzvv.by DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ The Walter Collective Vodka, Washington, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $28 www.thewaltercollective.com DOUBLE GOLD MEDAL ■ Underground Spirits Signature Vodka, Australia 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $80 www.undergroundspirits.co.uk GOLD MEDAL ■ Bedlam Vodka, North Carolina, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $22 www.bedlamvodka.com GOLD MEDAL ■ Caledonia Spirits Barr Hill Vodka, Vermont, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $58 www.caledoniaspirits.com GOLD MEDAL ■ Charleston Distilling King Charles Vodka, South Carolina, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $25 www.charlestondistilling.com GOLD MEDAL ■ Deep Ellum All-Purpose Vodka, Texas, USA 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $21 GOLD MEDAL ■ EFFEN® Original Vodka, Holland 40% ABV RETAIL PRICE: $30 www.beamblobal.com -

Gunpowder - EB 1911

gunpowder - EB 1911 Editor A.W.J Graham Kerr & picture editor C.H blackwood RESEARCH guide V. 2020 EncyclopÆdia BRITANNICA 1911 The Fortress Study Group is a registered charity (No.288790) founded in 1975. It is an international group whose aim is to advance the education of the public in all aspects of fortification and their armaments, especially works constructed to mount or resist artillery. Acknowledgements Each of these Research Guides come from a collection of Encyclopædia Britannica dated 1911, that I had inherited from my fathers library although somewhat out- dated today, the historical value is still of interest. They are a stand-alone booklets, available to members through the website for downloading. Hard copies are available at a cost for printing and postage and packing. We have been able to do this as a team and my thanks goes to Charles Blackwood who has edited the maps, diagrams and some photographs. A number of photo- graphs have been used from other sources all of which are copyrighted to their author. The editor apologises in advance for any mistakes or inadvertent breach of copyright, with thanks to Wikipedia, Wikisource and Google Earth, where we have used them. This publication ©AWJGK·FSG·2020 Contents GUNPOWDER page 3 Cover picture: Ballincollig Gunpowder Mill, Ireland—CHB 2013 Other Research Guides OS Research Guide I OS Research Guide VII Armour Plate Fortifications & Siegecraft OS Research Guide II OS Research Guide VIII Artillery Ordnance OS Research Guide III OS Research Guide IX Ammunition Ballistics OS Research Guide IV OS Research Guide X Explosives Castles I OS Research Guide V OS Research Guide XI Gunpowder Castles II OS Research Guide VI OS Research Guide XII Range Finding Castles III 2 GUNPOWDER Gunpowder, an explosive composed of saltpetre, charcoal and sulphur. -

Drinks List Diplomatico Blanco Rum Rittenhouse Rye Courvoisier VSOP Cognac Grenadine Lemon Juice

CLASSICS Pre - Prohibition Fish house punch £7 Courvoisier VSOP cognac Plantation 5 YO Rum Peach Liqueur Lemon Juice Aviation £7 Hayman’s Old Tom Gin Miclo Violet Liqueur Luxardo Maraschino Lemon Juice Post - Prohibition The Last Word £7 Colonel Fox’s Gin Green Chartreuse Luxardo Maraschino Lime Juice 12-Mile Limit £7.50 DrINKS LISt Diplomatico Blanco Rum Rittenhouse Rye Courvoisier VSOP Cognac Grenadine Lemon Juice TWITTER NITEHAWKSBAR FACEBOOK NITEHAWKSBAR INSTAGRAM nitehawksbar Nitehawks Signature DrinkS Guest Selection from The Poison Cabinet Down Mexico Way £8 Lynn Collins £7 La Penca Mezcal Lychee infused Beefeater Gin Smoked Pineapple Jam Lemongrass Tea infused St. Germain Elderflower Liqueur Chipotle Tincture lemon Juice Lime Juice Fentimans Ginger Beer Chipotle Salt Hornroot Sour £7 Cosmopolis £7 Durham Vodka Beefeater Gin Jasmine Tea Syrup Red Berry Tea Syrup Fresh Ginger Yellow Chartreuse Grapefruit Bitters Lime Juice Lemon Juice The Ridgewray £7.50 Tiki Bow Tie £7.50 Wray and Nephews Overproof Plantation 3 Star Silver Green Chartreuse Plantation 5 YO Luxardo Maraschino Plantation Overproof Rum Angostura Bitters Luxardo Amaretto Lime Juice Cointreau Orange Liqueur Sugar Syrup Lime Juice Pineapple Jam I Never Liked You Anyway £7.00 Buffalo Trace Bourbon Frangelico The Crimson Smoke £8 Calvados Compass Box Peat Monster Whisky Apple Juice Brakemann Cherry Jenever Cinnamon Bitters Campari Cocchi Americano The Nitehawk £7 Rhubarb Bitters Maker’s Mark Bourbon Homemade Stout & Vanilla Coffee Syrup Colour Coffee Cold Drip Frangelico. -

Paradigm Shifts in Biology of the 19Th Century - "Theory of Natural Selection" by Darwin and "Negation of Spontaneous Generation Theory" by Pasteur

Paradigm shifts in biology of the 19th century - "Theory of natural selection" by Darwin and "Negation of spontaneous generation theory" by Pasteur Here I will briefly describe the history of the theory on the origin of species. Until recently, the majority of naturalists believed that all species were invariable and created separately. This view has been maintained eloquently by many writers. However, only a small number of naturalists believed that species were subject to transformation, and the existing life forms are the true descendants of preceding generations of preceding forms of life. (Charles Darwin “The Origin of Species” p. 1) As you go down the chain of animals from the most complete to the most incomplete, we are faced with the singular situation of the gradual degradation in the configuration of the system - it is natural that I should think that the various life forms produced by life are born in sequence, developing from the simplest form to the most structured form. (Jean Baptiste Lamarck, “Animal Philosophy”, p. 8) How could a material transform to a living organism by itself. In other words, could a living form come into existence without parent and without ancestors? That is the problem that requires a solution. Actually it must be said that the belief in spontaneous generation has been the belief of many eras. It was believed in ancient times and it is debated more and more in modern times. What I am rebutting is this belief. (Louis Pasteur, “Consideration of Spontaneous Generation Theory”) 1 This chapter will describe the outline of the paradigm shift experienced by 20th century physics and 19th century biology. -

The Entire Story of Ketel One® Vodka Is on the Bottle

THE ENTIRE STOry OF KETEL ONE® VODKA IS ON THE BOTTLE 1 Ketel One® vodka 5 Schiedam, Holland The Ketel One® vodka name is derived A town no one’s heard of but from Distilleerketel No.1, a Dutch everyone’s grateful for! Sometimes 300 years of spirit distillation has word meaning ‘pot still’. regarded as one of the capitals of spirits, the place where brandy and inspired what we believe is the 2 Copper pot still jenever (Dutch gin) were apparently best vodka in the world Here on the label there is a picture invented. of the original copper pot still, ‘Distilleerketel No.1’ – still burning 6 Nolet family, 10 generations brightly today, after which the vodka On the label we can see the Nolet is named. family crest and if we turn the bottle around we can see the names of the 10 3 Crafted from small batches generations of the family. A member of Ketel One® vodka is crafted from small the Nolet family approves every final batches using copper pot stills together production run. with modern distilling techniques, at the Nolet family distillery, resulting in 7 Traditional bottle a distinctive, crisp and sophisticated The bottle was designed in the style of taste. an original Dutch stone spirits bottle. 4 Nolet Distillery: 1691 8 High neck The distillery was founded over 300 The neck of the bottle was increased years ago in 1691. in height at the request of bartenders, so that they could get a better hold of it in order to craft some of the world’s greatest cocktails. -

BEST Distillers Malts for the Best Spirits

BEST Distillers Malts For The Best Spirits 1 WALLERTHEIM PRODUCTION/LOGISTICS KREIMBACH-KAULBACH PRODUCTION HEIDELBERG HEADQUARTERS 2 BESTMALZ PROFILE Palatia Malz GmbH is a traditional German Careful moisture control, sufficient time for family business that sells its products under germination, slow kilning and extremely the “BESTMALZ” brand in Germany and gentle roasting are features of state-of-the- abroad. The company was established as a art, modern malt production at BESTMALZ. flour mill in 1899 and converted into a malt house in 1904. Ever since, the family-owned RELIABLE AND SUSTAINABLE malting business has produced top-grade PRODUCTION products from barley, wheat and other We monitor our certified production process- grains that have gained recognition and es and pursue resource-efficient energy and respect in the company’s markets at home environmental management. We continu- and abroad. ously enhance our process-related quality assurance and our in-house documentation LOCATED IN THE MIDST OF NATURE systems as a matter of course. The company’s main production facility in Kreimbach-Kaulbach near Kaiserslautern OUR PHILOSOPHY was joined in the 1980s by a second malt As a mid-sized, family-owned company, house in Wallertheim near Mainz. The com- we take a long-term view to our business pany has its headquarters in Heidelberg. Set operations and planning, reinvesting a large at the heart of the best regions for cultivat- portion of our profits back into the compa- ing barley in Germany, the two production ny and conducting research and product plants currently process almost 90,000 tons development systematically as part of the of barley and other grains. -

Rosalia's Menagerie the Spirits List

rosalia’s menagerie the spirits list Dear Guest... Welcome to my spirits collection. Lovingly curated and chosen with care. Always updated with our unique and exclusive finds. Love Rosalia ABSINTHE A Angelique Verte AMARI & BITTERS B Aperol Becherovka Campari Cynar C Fernet Branca Montenegro Picon Biere Wynand Fockink Singelburger D Wynand Fockink Prinseburger Zucca Rabarbaro E AGAVE Calle 23 Blanco Calle 23 Reposado F Del Maguey Via Mezcal G BRANDY Laird’s Straight Apple Brandy Le Basque VSOP Armagnac H Pierre Huet Calvados COGNAC Pierre Ferrand 1840 Original Formula Cognac I Merlet VS GIN Bobby’s Damrak Death’s Door Dutch Courage Barrel Aged Loopuyt Nolet’s Silver Rutte Celery Gin Rutte Sloe Gin VL92 Vordings JENEVER & KORENWIJN Amsterdamse Ketels Shiso Jenever J Bakers Best Bols Corenwyn 2 years Bols Corenwyn 4 years K Bols Corenwyn 6 years Bols Corenwyn 10 years Bols Jonge Bols Genever Bols 100% maltwine Bols Wassende Maen Corenwyn Bols Single Barrel - 2008 Delfts Zwart Filliers 0 years Filliers 8 years Filliers 12 years Filliers 17 years Filliers 21 years Filliers 1997 Vintage Hooghoudt Korenwijn Jajem Jonge Jenever Kever Genever Ketel 1 Jonge Ketel 1 Matuur Mokum Moonshine Notaris Bartender’s Choice Notaris Maltwine Notaris VXO Old Schiedam 1792 recipe Onder De Boompjes 100% Maltwine Onder De Boompjes Korenwijn Rutte 5 year Grain Genever Rutte Old Simon Rutte XO Koornwyn Rutte Paradyswyn Rutte Single Oat Genever Rutte Celery Ginnever Roggenaer 15 year old - pre ‘88 bottling Texels Oorlam Van Kleef 3 year Old Van Wees Mirakel van -

Biological Sciences

A Comprehensive Book on Environmentalism Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Introduction to Environmentalism Chapter 2 - Environmental Movement Chapter 3 - Conservation Movement Chapter 4 - Green Politics Chapter 5 - Environmental Movement in the United States Chapter 6 - Environmental Movement in New Zealand & Australia Chapter 7 - Free-Market Environmentalism Chapter 8 - Evangelical Environmentalism Chapter 9 -WT Timeline of History of Environmentalism _____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES _____________________ A Comprehensive Book on Enzymes Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Introduction to Enzyme Chapter 2 - Cofactors Chapter 3 - Enzyme Kinetics Chapter 4 - Enzyme Inhibitor Chapter 5 - Enzymes Assay and Substrate WT _____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES _____________________ A Comprehensive Introduction to Bioenergy Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Bioenergy Chapter 2 - Biomass Chapter 3 - Bioconversion of Biomass to Mixed Alcohol Fuels Chapter 4 - Thermal Depolymerization Chapter 5 - Wood Fuel Chapter 6 - Biomass Heating System Chapter 7 - Vegetable Oil Fuel Chapter 8 - Methanol Fuel Chapter 9 - Cellulosic Ethanol Chapter 10 - Butanol Fuel Chapter 11 - Algae Fuel Chapter 12 - Waste-to-energy and Renewable Fuels Chapter 13 WT- Food vs. Fuel _____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES _____________________ A Comprehensive Introduction to Botany Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Botany Chapter 2 - History of Botany Chapter 3 - Paleobotany Chapter 4 - Flora Chapter 5 - Adventitiousness and Ampelography Chapter 6 - Chimera (Plant) and Evergreen Chapter