A Residence at Sierra Leone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Or C\^Iing Party. \

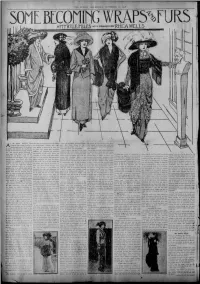

r 3 the season advances one's that they are their own excuse for being— This type is prettily developed In mole- the dismay of those observers who dislike thoughts turn toward evening en- as reconstructed emeralds and ruMes skin. Mrs. Frank Nelson, Jr., has a their fidgety movements and would fain scarf and big pillow muff of this fur enjoy the classic calm of the unbeplum- tertainments, and it is the toilette have gained a distinction of their own do soiree and de theatre that which she wears very becomingly. aged bandeau. manteau by their real beauty and excellence. There is also a scarf of tlie black One of the quaintest coiffure ornaments occupy the attention of the lady of fash- big Moreover, fur imitations are absolutely fur In Mr. Wells’ sketch. It is fitted in town is black velvet and ion. The evening gowns mentioned in lynx bright green if the sisters and I Indispensable wives, about the neck and at one end Is orna- tulle. It Is clasped in the back with a these pages from time to time and de- of something to give in celebration of Many families hold the bridal veil as one popular colors in what is known as tho daughters of others than multi-million- a of made in the mented with handsome sil£ frog, pro- narrow' hand of mother pearl, very scribed by pen pictures Christman has begun to crowd the shops. of the most precious of heirlooms, to b© “made*’ veils and these with their well aires are to be with ducing that “one-sided” effect at once thin and very lustrous. -

AD Ungeons & D Ragon R Oleplay in G G Ame S Upplement IS SUE 3

ISSUE 391 | SEptEmbEr 2010 A Dungeons & Dragons® Roleplaying Game Supplement ® Contents Features 5 Dark Sun: Hunters in tHe WastelanD 41 Class Acts: Essentials PyromanCer By Chris Sims By Mike Mearls Ferocious beasts roam the wild places of Athas, making them deadly regions The school of pyromantic magic attracts a certain type of mage: the for travelers. But the wastelands are also fertile ground for hunters. aggressive, the impatient, the angry, and sometimes the doomed. 12 ShaDar-kai in tHe Realms 45 Class Acts: Essentials Staff FigHter By Robert J. Schwalb By Rodney Thompson The shadar-kai are new to Faerûn, and they have much to learn as they The staff is an ancient and simple weapon. Its unpretentious appearance can explore their new home. mask an efficient lethality. 18 Playtest: Essentials Assassin 49 Winning RaCes: DWarves of tHe All-FatHer By Rodney Thompson By Matt Sernett The Player’s Essentials assassin makes its entrance in playtest form. We want Dwarves honor Moradin through prayer and tradition. We honor dwarves your feedback! with a selection of new feats. 38 Class Acts: BattleminDs 52 Winning RaCes: Genasi By Scott Fitzgerald Gray By Peter Schaefer The Ghosts of Nerath are among the last remnants of that fallen empire. Too many genasi lead lives of forced servitude in the Elemental Chaos. The Their quest is to restore the ancient glory that was lost. Amethyst Sea exists to free them. 55 Winning RaCes: Muls By Robert J. Schwalb Muls are iconic to the harsh world of Athas, but you can still import them to other campaigns. -

Sample File 100 Years Have Passed Since Mankind Revolted and Slew the Sorcerer Kings

Sample file 100 years have passed since mankind revolted and slew the Sorcerer Kings. Now, the survivors of five ancient empires begin to rebuild, placing new lives and hopes on the ashes of old. However, even as life continues an ancient and forgotten evil stirs awaiting its moment to strike against mankind. Explore a war-torn land where the struggle for survival continues as new kingdoms arise to impose their will upon the masses. Vicious warlords fight to control territories carved out of the Fallen Empires. Imposing magicians emerge claiming the legacy of the Sorcerer Kings. High Priests of long forgotten gods and goddesses amass wealth in the name of divine right while warrior-monks, devoted to a banished god, patrol the lands bringing justice to people abandoned by their rulers. Tales of the Fallen Empire is a classic Swords and Sorcery setting compatible with the Dungeon Crawl Classics Role Playing Game. Within these pages is a detailed post-apocalyptic fantasySample setting file taking you through an ancient realm that is fighting for its survival and its humanity. Seek your fortune or meet your fate in the burning deserts of the once lush and vibrant land of Vuul, or travel to the humid jungles of Najambi to face the tribes of the Man-Apes and their brutal sacrificial rituals. Within this campaign setting you will find: D 6 new classes: Barbarian, Witch, Draki, Sentinel, Man-Ape, & Marauder D Revised Wizard Class (The Sorcerer) D New Spells D New Creatures D Seafaring and Ritual Magic Rules D A detailed setting inspired by the works of Fritz Lieber, Robert E. -

Cartography and the Conception, Conquest and Control of Eastern Africa, 1844-1914

Delineating Dominion: Cartography and the Conception, Conquest and Control of Eastern Africa, 1844-1914 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert H. Clemm Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor Alan Beyerchen Ousman Kobo Copyright by Robert H Clemm 2012 Abstract This dissertation documents the ways in which cartography was used during the Scramble for Africa to conceptualize, conquer and administer newly-won European colonies. By comparing the actions of two colonial powers, Germany and Britain, this study exposes how cartography was a constant in the colonial process. Using a three-tiered model of “gazes” (Discoverer, Despot, and Developer) maps are analyzed to show both the different purposes they were used for as well as the common appropriative power of the map. In doing so this study traces how cartography facilitated the colonial process of empire building from the beginnings of exploration to the administration of the colonies of German and British East Africa. During the period of exploration maps served to make the territory of Africa, previously unknown, legible to European audiences. Under the gaze of the Despot the map was used to legitimize the conquest of territory and add a permanence to the European colonies. Lastly, maps aided the capitalist development of the colonies as they were harnessed to make the land, and people, “useful.” Of special highlight is the ways in which maps were used in a similar manner by both private and state entities, suggesting a common understanding of the power of the map. -

Twenty Years in the Himalaya

=a,-*_ i,at^s::jg£jgiTg& ^"t^f. CORNELL UNIVERSITY Hi. LBRAR^ OLIN LIBRARY - CIRCULATION DATE DUE 1 :a Cornell University Library DS 485.H6B88 Twenty years In the Himalaya, 3 1924 007 496 510 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924007496510 TWENTY YEARS IN THE HIMALAYA (^- /^^vc<- 02. <f- \t,V^. fqi<o- LOHDON Er)"WAHE ATlTSIOLri TWENTY YEAES IN THE HIMALAYA BY Major the Hon. C. G. BRUCE, M.V.O. FIFTH GOORKHA RIFLES WITH 60 ILLUSTRATIONS AND A MAP LONDON ' EDWARD ARNOLD ';i ipubUsbcr to tbe 3n5(a ©fftcc rr 1910 ' '\ All rights reserved fr [) • PREFACE I AM attempting in this book to give to those interested in " Mountain Travel and Mountain Exploration, who have not been so luckily placed as myself, some account of the Hindu Koosh and Himalaya ranges. My wanderings cover a period of nineteen years, during which I have not been able to do more than pierce these vast ranges, as one might stick a needle into a bolster, in many places ; for no one can lay claim to a really intimate knowledge of the Himalaya alone, as understood in the mountaineering sense at home. There are still a great number of districts which remain for me new ground, as well as the 500 miles of the Himalaya included in " Nepal," which, to all intents and purposes, is still unexplored. My object is to try and show the great contrasts between people, country, life, etc. -

The Construction of National Culture and Identity in a Province: the Case of the People's House of Kayseri

THE CONSTRUCTION OF NATIONAL CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN A PROVINCE: THE CASE OF THE PEOPLE'S HOUSE OF KAYSERI A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY FULYA BALKAR IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDIA AND CULTURAL STUDIES DECEMBER 2019 i ii Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar Kondakçı Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Lütfi Doğan Tılıç (Başkent Uni., HIT) Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan (METU, ADM) Assoc. Prof. Barış Çakmur (METU, ADM) iii ii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Fulya Balkar Signature : iii ABSTRACT THE CONSTRUCTION OF NATIONAL CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN A PROVINCE: THE CASE OF THE PEOPLE'S HOUSE OF KAYSERI Balkar, Fulya M.S., Department of Media and Cultural Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan December 2019, 249 pages This thesis focuses on the Kayseri House experience in early republican period and aims to explore how the narratives of national culture and identity were constructed in a so-called conservative province in the context of the Kayseri House. -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

The Ends of Slavery in Barotseland, Western Zambia (C.1800-1925)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Hogan, Jack (2014) The ends of slavery in Barotseland, Western Zambia (c.1800-1925). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/48707/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html The ends of slavery in Barotseland, Western Zambia (c.1800-1925) Jack Hogan Thesis submitted to the University of Kent for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2014 Word count: 99,682 words Abstract This thesis is primarily an attempt at an economic history of slavery in Barotseland, the Lozi kingdom that once dominated the Upper Zambezi floodplain, in what is now Zambia’s Western Province. Slavery is a word that resonates in the minds of many when they think of Africa in the nineteenth century, but for the most part in association with the brutalities of the international slave trades. -

Religion in the Public Sphere

Religion in the Public Sphere Ars Disputandi Supplement Series Volume 5 edited by MAARTEN WISSE MARCEL SAROT MICHAEL SCOTT NIEK BRUNSVELD Ars Disputandi [http://www.ArsDisputandi.org] (2011) Religion in the Public Sphere Proceedings of the 2010 Conference of the European Society for Philosophy of Religion edited by NIEK BRUNSVELD & ROGER TRIGG Utrecht University & University of Oxford Utrecht: Ars Disputandi, 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Ars Disputandi, version: September 14, 2011 Published by Ars Disputandi: The Online Journal for Philosophy of Religion, [http://www.arsdisputandi.org], hosted by Igitur publishing, Utrecht University Library, The Netherlands [http://www.uu.nl/university/library/nl/igitur/]. Typeset in Constantia 9/12pt. ISBN: 978-90-6701-000-9 ISSN: 1566–5399 NUR: 705 Reproduction of this (or parts of this) publication is permitted for non-commercial use, provided that appropriate reference is made to the author and the origin of the material. Commercial reproduction of (parts of) it is only permitted after prior permission by the publisher. Contents Introduction 1 ROGER TRIGG 1 Does Forgiveness Violate Justice? 9 NICHOLAS WOLTERSTORFF Section I: Religion and Law 2 Religion and the Legal Sphere 33 MICHAEL MOXTER 3 Religion and Law: Response to Michael Moxter 57 STEPHEN R.L. CLARK Section II: Blasphemy and Offence 4 On Blasphemy: An Analysis 75 HENK VROOM 5 Blasphemy, Offence, and Hate Speech: Response to Henk Vroom 95 ODDBJØRN LEIRVIK Section III: Religious Freedom 6 Freedom of Religion 109 ROGER TRIGG 7 Freedom of Religion as the Foundation of Freedom and as the Basis of Human Rights: Response to Roger Trigg 125 ELISABETH GRÄB-SCHMIDT Section IV: Multiculturalism and Pluralism in Secular Society 8 Multiculturalism and Pluralism in Secular Society: Individual or Collective Rights? 147 ANNE SOFIE ROALD 9 After Multiculturalism: Response to Anne Sofie Roald 165 THEO W.A. -

An Embellishment: Purdah

An Embellishment: Purdah For An Embellishment: Purdah,i a two-part text installation for an exhibition, Spatial Imagination (2006), I selected twelve short extracts from ‘To Miss the Desert’ and rewrote them as ‘scenes’ of equal length, laid out in the catalogue as a grid, three squares wide by four high, to match the twelve panes of glass in the west-facing window of the gallery looking onto the street. Here, across the glass, I repeatedly wrote the word ‘purdah’ in black kohl in the script of Afghanistan’s official languages – Dari and Pashto.ii The term purdah means curtain in Persian and describes the cultural practice of separating and hiding women through clothing and architecture – veils, screens and walls – from the public male gaze. The fabric veil has been compared to its architectural equivalent – the mashrabiyya – an ornate wooden screen and feature of traditional North African domestic architecture, which also ‘demarcates the line between public and private space’.iii The origins of purdah, culturally, religiously and geographically, are highly debated,iv and connected to class as well as gender.v The current manifestation of this gendered spatial practice varies according to location and involves covering different combinations of hair, face, eyes and body. In Afghanistan, for example, under the Taliban, when in public, women were required to wear what has been termed a burqa, a word of Pakistani origin. In Afghanistan the full-length veil is more commonly known as the chadoree or chadari, a variation of the Persian chador, meaning tent.vi This loose garment, usually sky-blue, covers the body from head to foot. -

Colonial and Orientalist Veils

Colonial and Orientalist Veils: Associations of Islamic Female Dress in the French and Moroccan Press and Politics Loubna Bijdiguen Goldmiths College – University of London Thesis Submitted for a PhD in Media and Communications Abstract The veiled Muslimah or Muslim woman has figured as a threat in media during the past few years, especially with the increasing visibility of religious practices in both Muslim-majority and Muslim-minority contexts. Islamic dress has further become a means and technique of constructing ideas about the ‘other’. My study explores how the veil comes to embody this otherness in the contemporary print media and politics. It is an attempt to question constructions of the veil by showing how they repeat older colonial and Orientalist histories. I compare and contrast representations of the dress in Morocco and France. This research is about how Muslimat, and more particularly their Islamic attire, is portrayed in the contemporary print media and politics. My research aims to explore constructions of the dress in the contemporary Moroccan and French press and politics, and how the veil comes to acquire meanings, or veil associations, over time. I consider the veil in Orientalist, postcolonial, Muslim and Islamic feminist contexts, and constructions of the veil in Orientalist and Arab Nahda texts. I also examine Islamic dress in contemporary Moroccan and French print media and politics. While I focus on similarities and continuities, I also highlight differences in constructions of the veil. My study establishes the importance of merging and comparing histories, social contexts and geographies, and offers an opportunity to read the veil from a multivocal, multilingual, cross-historical perspective, in order to reconsider discourses of Islamic dress past and present in comparative perspective. -

The Portrayal of the Historical Muslim Female on Screen

THE PORTRAYAL OF THE HISTORICAL MUSLIM FEMALE ON SCREEN A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 SABINA SHAH SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES LIST OF CONTENTS List of Photographs................................................................................................................ 5 List of Diagrams...................................................................................................................... 7 List of Abbreviations.............................................................................................................. 8 Glossary................................................................................................................................... 9 Abstract.................................................................................................................................... 12 Declaration.............................................................................................................................. 13 Copyright Statement.............................................................................................................. 14 Acknowledgements................................................................................................................ 15 Dedication............................................................................................................................... 16 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................